under the Official Information Act 1982

Released

under the Official Information Act 1982

Released

under the Official Information Act 1982

Released

under the Official Information Act 1982

Released

5. Managing risks

5. Managing risks

Te whakahaere mōrea

What we want to see: New Zealand is a risk savvy nation that takes all practicable

steps to identify, prioritise, and manage risks that could impact the wellbeing and

prosperity of New Zealanders, and all who live, work, or visit here.

This priority is concerned with identifying and monitoring

In the construction sector, quantifying the potential risk

risks to our wellbeing, taking action to reduce our existing

expected in the lifetime of a building, bridge, or other

levels of risk (‘corrective risk management’), minimise

critical infrastructure drives the creation and modification

the amount of new risk we create (‘prospective risk

of building codes. In the land-use and urban planning

management’), and ensuring that everyone has the data,

sectors, robust analysis of flood (and other) risk likewise

information, knowledge, and tools they need to be able to

drives investment in flood protection and possibly effects

make informed decisions about resilience.

changes in insurance as well. In the insurance sector, the

quantification of disaster risk is essential, given that the

We have seen how we already have a considerable amount

solvency capital of most insurance companies is strongly

of risk in our society through the hazards we face, the assets

influenced by their exposure to risk.

we have exposed to those hazards, and the vulnerability of

people, assets, and services to impacts. It is important for

A critical part of understanding and managing risk is

us to try and reduce that level of existing risk so that the

understanding the full range of costs involved in disasters,

chances of disaster are reduced, and/or the impacts are

both the direct costs from damage and the more indirect

reduced if or when hazardous events occur.

and intangible costs resulting from flow-on effects and

social impact. We also need to identify the range of financial

At the same time, it is critical to recognise how we

instruments that may be available to support the activities

inadvertently add to that risk through poor development

designed to reduce our risk and build our resilience,

choices, including land-use and building choices. Planning

including those promoted in this Strategy.

for resilience at the outset of new projects is by far the

cheapest and easiest time to minimise risk and has the

potential to significantly reduce disaster costs in the future.

Risk information provides a critical foundation for managing

disaster risk across all sectors. At the community level,

an understanding of hazard events—whether from

living memory or oral and written histories— can inform

under the Official Information Act 1982

and influence decisions on preparedness, including

life-saving evacuation procedures and the location of

important facilities.

Released

DRAFT FOR CONSULTATION | Rautaki Manawaroa Aituā ā-Motu |

National Disaster Resilience Strategy 29

The six objectives designed to progress the priority of managing risks are at all levels to:

Objective

What success looks like; by 2030:

1 Identify and understand risk scenarios

There is an agreed, standardised, and widely-used methodology for

(including the components of hazard,

assessing disaster risks at a local government, large organisation,

exposure, vulnerability, and capacity),

and central government level. This includes making use of scientific,

and use this knowledge to inform

indigenous, and local knowledge. Risks can be aggregated and viewed

decision-making

at a national or sub-national level, and the results inform the risk

assessment efforts of others. Businesses and small organisations

can make use of a simplified version to assess their own risks, and

make decisions about courses of action. Particular attention is paid

to assessing and reducing the vulnerability of people and groups,

including to take an inclusive, participatory approach to planning and

preparedness.

2 Put in place organisational structures

The governance of risk and resilience in NZ is informed by multi-

and identify necessary processes -

sectoral views and participation including the private sector, not-

including being informed by community for-profit, and other community representatives. Progress on risk

perspectives - to understand and act on

management and towards increased resilience is publicly tracked, and

reducing risks

interventions evaluated for effectiveness.

3 Build risk awareness, risk literacy, and

There is an agreed ‘plain English’ lexicon for risk, including better visual

risk management capability, including

products for describing the risk of any situation, hazard, product, or

the ability to assess risk

process; government agencies and science organisations regularly

communicate with the public about risks in a timely and transparent

manner, and in a way that is understandable and judged effective by

the public. This transparency of risk information leads to more inclusive

conversations on the acceptability of risk.

4 Address gaps in risk reduction policy

We have had a national conversation – including with affected and

(particularly in the light of climate

potentially-affected communities – about how to approach high hazard

change adaptation)

areas, and we have a system level-response (including central and local

government) with aligned regulatory and funding/financing policies in

place.

5 Ensure development and investment

Communities value and accept having resilience as a core goal for

practices, particularly in the built

all development, recognising that this may involve higher upfront

and natural environments, are risk-

costs though greater net benefits in the long term; plans, policies and

aware, taking care not to create any

regulations are fit for purpose, flexible enough to enable resilient

under the Official Information Act 1982

unnecessary or unacceptable new risk

development under a variety of circumstances, and can be easily

adapted as risks become better understood; developers aim to exceed

required standards for new development, and may receive appropriate

recognition for doing so; earthquake prone building remediation meets

required timeframes and standards.

6 Understand the economic impact of

There is an improved understanding of the cost of disasters and

disaster and disruption, and the need

disruption, including the economic cost of social impact; we are

for investment in resilience; identify

routinely collecting data on disruption, and using it to inform decision-

Released

and develop financial mechanisms that

making and investment in resilience; there is a clear mix of funding and

support resilience activities

incentives in place to advance New Zealand’s disaster risk management

priorities and build resilience to disasters.

30 National Disaster Resilience Strategy | Rautaki Manawaroa Aituā ā-Motu | DRAFT FOR CONSULTATION

6. Effective response to and recovery

from emergencies

6. Effective response to and recovery

from emergencies

Te urupare tōkita me te whakaora

mai i ngā ohotata

What we want to see: New Zealand has a seamless end-to-end emergency

management system that supports effective response to and recovery from

emergencies, reducing impacts, caring for individuals, and protecting the long-

term wellbeing of New Zealanders.

Responding to, and recovering from, disasters remains

There are many strengths in New Zealand’s emergency

– and may always remain – our toughest challenge. This

management system. Our system is set up to deal with

is when we have most at risk, when human suffering is

‘all hazards and risks’, we work across the ‘4Rs’, and

potentially at its greatest, and when there is most threat to

engage communities in emergency management. There is

our property, assets, and economic wellbeing.

passion and commitment from all those who respond to

emergencies, paid staff, volunteers, and communities alike.

The response phase can involve frenetic pace, confusion,

pressure, and has the highest requirement for good

In recent years, significant global and local events have

decision-making and effective communications. Recovery

changed how we think about emergency management.

can be the most complex, requiring inclusive and

The Canterbury earthquakes are still fresh in our minds

participatory approaches, reflection and careful planning,

as a nation. A changing climate means we could get more

but needs to be balanced with a need for momentum and

frequent storms and floods. Globally, we see the impact

progress.

of tsunami, pandemics, industrial accidents, terrorism

incidents and other hazards that cause serious harm

Both hold the opportunity to minimise impacts before

to people, environments, and economies. Our risks are

they get out of control, to limit the suffering of individuals,

changing. Our emergency management system must

families/whānau, communities and hapū, to manage risk

change too to ensure it works when we need it.

and build in resilience for an improved future.

This priority aims to further progress the advancements

we have made in responding to and supporting recovery

from emergencies over the last 16 years since the CDEM Act

under the Official Information Act 1982

came into effect. It incorporates the Government’s decisions

on the Review into

Better Responses to Natural Disasters and

Other Emergencies (2017), and it looks at the next generation

of capability and capacity we require. It aims to modernise

the discipline of emergency management and ensure

we are ‘fit-for-purpose’, including to address some of the

emerging issues of maintaining pace with media and social

media, responding to new and complex emergencies,

enabling and empowering all-of-society participation, and

the type of command, control, and leadership required

Released

to ensure rapid, effective, inclusive, and compassionate

response and recovery.

DRAFT FOR CONSULTATION | Rautaki Manawaroa Aituā ā-Motu |

National Disaster Resilience Strategy 31

The six objectives designed to progress the priority of effective response to and recovery from emergencies are to:

Objective

What success looks like; by 2030:

7 Ensure that the safety and wellbeing of

There is renewed levels of trust and confidence in the emergency

people is at the heart of the emergency

management system. In emergencies, the safety, needs, and wellbeing of

management system

affected people are the highest priority. The public know what is going on,

what to expect, and what to do: hazard warnings are timely and effective,

and incorporate new technology and social science; strategic information

is shared with stakeholders, spokespeople, and the media, so they get

the right advice at the right time; and public information management is

resourced to communicate effectively with the public, through a variety

of channels, in formats that are sensitive to the needs of the most

vulnerable.

8 Build the relationship between

There is good collaboration and coordination between iwi and emergency

emergency management organisations

management agencies in relation to emergency management.

and iwi/groups representing Māori,

Engagement with iwi recognises the mana and status of Māori as tangata

to ensure greater recognition,

whenua, and provides practical commitment to the Treaty of Waitangi,

understanding, and integration of iwi/

including the principles of partnership, participation, and protection.

Māori perspectives and tikanga in

Iwi are represented on Coordinating Executive Groups and provide

emergency management

advice in relation to governance and planning. CDEM Groups work with

marae in their region that want to have a role in response and recovery,

to understand their tikanga, support planning and development of

protocols, and establish clear arrangements for reimbursement of

welfare-related expenses.

9 Strengthen the national leadership of

There is more directive leadership of the emergency management

the emergency management system

system, including setting national standards for emergency management,

so there is a consistent standard of care across the country. There is

strengthened stewardship of the system, including a clear understanding

of, and arrangements for, lead and support roles for the full range of

national risks.

10 Ensure it is clear who is responsible for

Legislative and policy settings support plans at all levels that are clearer

what, nationally, regionally, and locally,

about how agencies will work together and who will do what. Updated

in response and recovery; empower

incident management doctrine provides clarity about roles and functions,

and enable community-level response,

and is used by all agencies to manage all events. At a regional level,

and ensure it is connected into wider

shared service arrangements are clear about local and regional roles,

coordinated responses, where necessary and mean better use of resources and better holistic service delivery

to communities. Communities, including the private and not-for-profit

sectors, are empowered to problem-solve and lead their own response

and recovery, while having connections into official channels to source

under the Official Information Act 1982

support and resources where needed.

11 Build the capability and capacity of the

All Controllers and Recovery Managers are trained and accredited; people

emergency management workforce for

fulfilling incident management roles have the appropriate training,

response and recovery

skills, experience and aptitude and volunteers are appropriately trained,

recognised, and kept safe in the system. Fly-in Teams undertake rapid

deployments in emergency response and recovery situations to support

local capability and capacity. The broader emergency management

workforce has increased competency in matters of diversity and

inclusiveness, including cultural competence, and disability-inclusive

Released

approaches.

12 Improve the information and

All stakeholders in the emergency management system have access to

intelligence system that supports

the same operational and technical information, which provides greater

decision-making in emergencies

awareness of the situation at hand, and allows timely and effective

decision-making.

32 National Disaster Resilience Strategy | Rautaki Manawaroa Aituā ā-Motu | DRAFT FOR CONSULTATION

7. Enabling, empowering, and supporting

community resilience

7. Enabling, empowering, and supporting

community resilience

Te whakapakari i te manawaroa o te iwi

What we want to see: New Zealand has a culture of resilience that means

individuals and families/whānau, businesses and organisations, communities

and hapū are empowered to take action to reduce their risks, connect with others,

and build resilience to shocks and stresses.

This Strategy promotes the strengthening of resilience in

infrastructure for example health care, education, culture

the social, cultural, economic, built, natural, and governance

and heritage facilities, banking and finance services,

environments, at all levels from individuals and families/

emergency services and the justice system, is recognised

whānau, to business and organisations, communities

as a critical element for healthy economies and stable

and hapū, cities and districts, and at the national level. It

communities. It enables commerce, movement of people,

promotes integrated, collective, and holistic approaches

goods and information, and facilitates society’s daily

and the goal of linking grassroots initiatives, with policy and

economic and social wellbeing.

programmes that empower, enable and support individuals

and communities.

The ability of infrastructure systems to function during

adverse conditions and quickly recover to acceptable

A key goal is to strengthen the culture of resilience in

levels of service after an event is fundamental to the

New Zealand, whereby New Zealanders see the value

wellbeing of communities. This Strategy supports

of resilience, and understand the range of actions they

other key policy and programmes in emphasising the

can take to limit their impacts, or the impacts on others,

importance of infrastructure resilience, in particular

and ensure the hazards, crises, and emergencies we will

for its role in supporting wider community resilience.

inevitably face do not become disasters that threaten our

This includes assessing the adequacy and capacity of

prosperity and wellbeing.

current infrastructure assets and networks, identifying

key interdependencies and cascading effects,

It is particularly important to ensure an inclusive approach,

progressively upgrading assets as practicable, and

including engaging with, and considering the needs of, any

identifying opportunities to ‘build back better’ in recovery

people or groups who have specific needs, or who are likely

and reconstruction.

to be disproportionately affected by disasters. Not all New

Zealanders, or those who work, live, or visit here, will have

under the Official Information Act 1982

the same capacity to engage, prepare, or build resilience.

It is critical that the needs of all people are accounted for,

including how we can best enable, empower, and support

people to achieve good outcomes.

Inclusive and participatory governance of disaster resilience

at the national, regional and local levels is an important

objective, including the development of clear vision, plans,

capability, capacity, guidance and coordination within and

Released

across sectors. Champions, partnerships, networks, and

coalition approaches are crucial, as well as the development

of increased recognition of the role culture plays in

resilience.

Infrastructure, including physical infrastructure for

example roads, bridges, airports, rail, water supply,

telecommunications and energy services, and social

DRAFT FOR CONSULTATION | Rautaki Manawaroa Aituā ā-Motu |

National Disaster Resilience Strategy 33

The six objectives designed to progress the priority of enabling, empowering, and supporting community resilience are at all

levels to:

Objective

What success looks like; by 2030:

13 Enable and empower individuals,

Emergency preparedness for all members of society, including

households, organisations, and

animals, is part of everyday life. More people are able to thrive through

businesses to build their resilience,

periods of crisis and change because they have adaptable plans

paying particular attention to those

to get through different emergency scenarios, access to regularly

people and groups who may be

maintained resources to draw on in an emergency, and established

disproportionately affected by disaster

networks of information and support. Public, private, and not-for-profit

organisations are able to thrive through periods of crisis and change

because they understand what they can do to improve their resilience,

and are investing in improving it. People and groups who have

particular needs, or who are likely to be disproportionately affected by

disasters, are included in planning and preparedness, and supported

to build their resilience.

14 Cultivate an environment for social

New methodologies and approaches mean that communities are

connectedness which promotes a

more knowledgeable about risks, are empowered to problem-solve,

culture of mutual help; embed a

and participate in decision-making about their future. Capabilities,

collective impact approach to building

capacity, and connectedness are key ideas. Organisations that support

community resilience

communities work together to coordinate activities, ensure their

efforts are mutually reinforcing (where possible), and track progress.

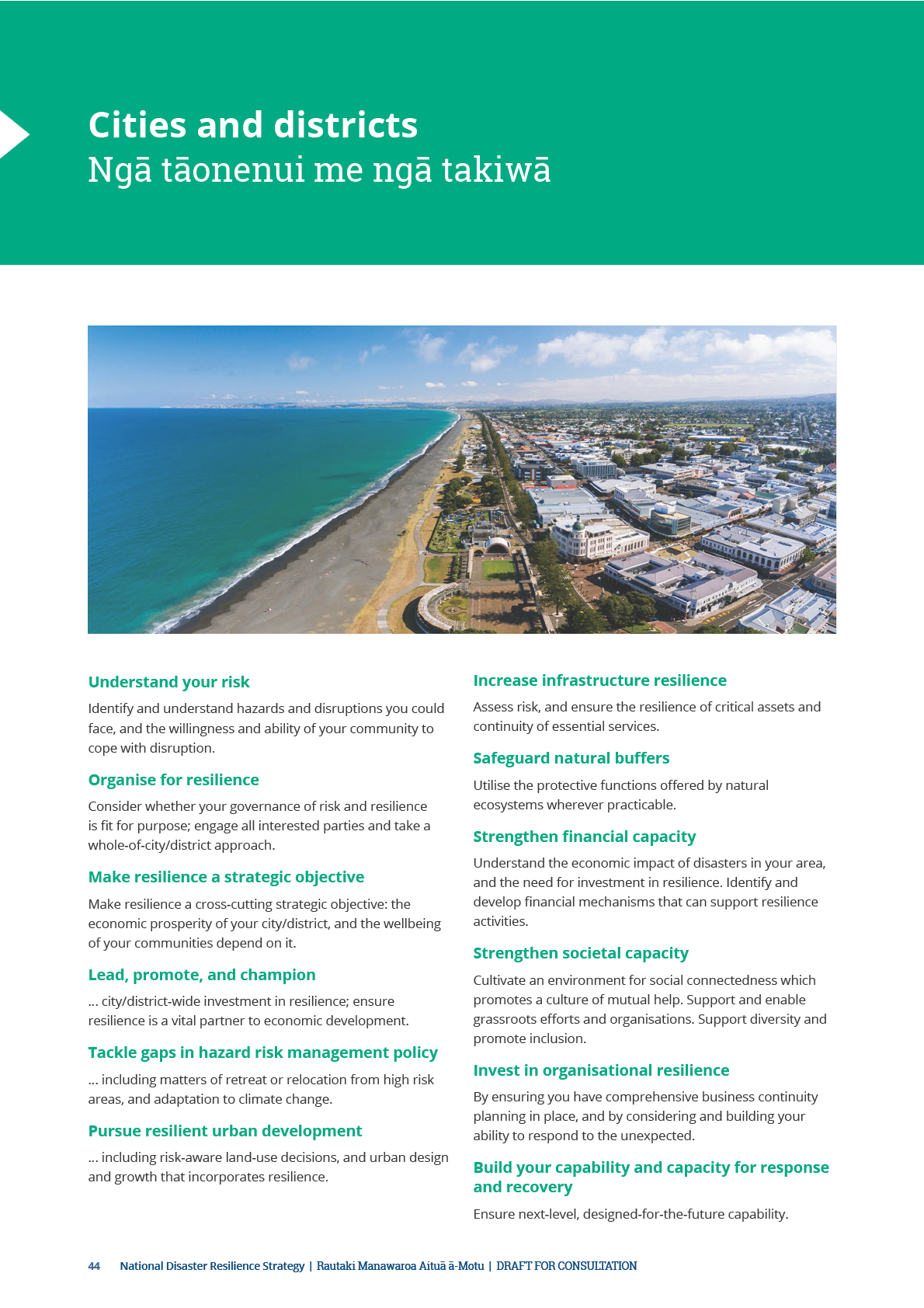

15 Take a whole of city/district/region

Local authorities and their partners have adopted strategic

approach to resilience, including to

objectives aimed at building resilience in their city/district, and work

embed strategic objectives for resilience

collaboratively with a broad range of stakeholders to steward the

in key plans and strategies

wellbeing and prosperity of the city/district.

16 Address the capacity and adequacy

We more fully understand infrastructure vulnerabilities, including

of critical infrastructure systems, and

interdependencies, cascading effects and impacts on society; we have

upgrade them as practicable, according

clarified and agreed expectations about levels of service during and

to risks identified

after emergencies, and see infrastructure providers that are working

to meet those levels (including through planning and investment),

and; we have improved planning for response to and recovery from

infrastructure failure.

17 Embed a strategic, resilence approach

There is significantly increased understanding of recovery principles

to recovery planning that takes account

and practice by decision-makers; readiness for recovery is based on a

of risks identified, recognises long-

strong understanding of communities and their desired outcomes and

under the Official Information Act 1982

term priorities and opportunities to

values, as well as the consequences local hazards might have on these

build back better, and ensures people

communities; in particular, it focuses on long-term resilience by linking

and communities are at the centre of

recovery to risk reduction, readiness, and response through actions

recovery processes

designed to reduce consequences on communities.

18 Recognise the importance of culture

There is an increased understanding and recognition of the role

to resilience, including to support

culture plays in resilience; there are improved multi-cultural

the continuity of cultural places,

partnership approaches to disaster planning and preparedness; and

institutions and activities, and to enable

there is substantially increased resilience to disasters including the

Released

the participation of different cultures

protection of cultural and historic heritage places, assets, and taonga

in resilience

(including marae).

34 National Disaster Resilience Strategy | Rautaki Manawaroa Aituā ā-Motu | DRAFT FOR CONSULTATION

under the Official Information Act 1982

Released

8. Our commitment to action

E paiherea ana mātau ki te mahi

Producing a strategy is not the end of thinking about resilience –

it’s the beginning.

Ehara te whakairo rautaki i te whakamutunga o te whakaaro mō te

manawaroa – he tīmatanga kē.

8.1 What happens next?

Efforts to tackle the challenge of accountability have

The job of the Strategy is to show what we want to achieve

traditionally tended to concentrate on improving the ‘supply

over the next ten years. It’s deliberately high level with

side’ of governance, including methods such as political

objectives broadly described. Specific actions to implement

checks and balances, administrative rules and procedures,

the Strategy are not included - doing so would make it long,

auditing, and formal enforcement processes.

cumbersome and inflexible.

These are still important, and will be built into the process

The Ministry of Civil Defence & Emergency Management

to monitor this Strategy. However, we also want to pay

will, during 2019, coordinate the preparation of a roadmap

attention to the ‘demand side’ of good governance:

of actions setting out how the Strategy objectives will be

strengthening the voice and capacity of all stakeholders

achieved. Its emphasis will be on work to be done over the

(including the public, and any groups disproportionately

next 3-5 years (and be updated overtime).

affected by disasters), to demand greater accountability and

responsiveness from authorities and service providers.

The roadmap will acknowledge the range of initiatives that

contribute to the Strategy’s objectives. Examples of these

Enhancing the ability of the public to engage in policy,

are:

planning, and practice is key.

• The implementation of the Emergency Management

We must find ever-more effective and practical ways to do

System Reforms to improve how New Zealand responds

this. This could include activities such as: representation

to natural disasters and emergencies

on governance or planning groups, deliberate efforts to

• Revised Civil Defence Emergency Management Group

engage different stakeholder groups on specific challenges,

plans and the National Civil Defence Emergency

citizen or civil society-led action, or utilising the whole new

Management Plan (which must be reviewed by

generation of engagement offered by social media.

December 2020)

• Climate change adaptation initiatives

8.3 Governance of this Strategy

The Strategy will be owned and managed by existing

The roadmap will include work about how best to give effect

governance mechanisms, including those through the

under the Official Information Act 1982

to the Strategy’s aim of a whole-of-society, inclusive, and

National Security System, and at a regional level by

collective approach to building resilience.

CDEM Groups.

Holding ourselves to account is paramount.

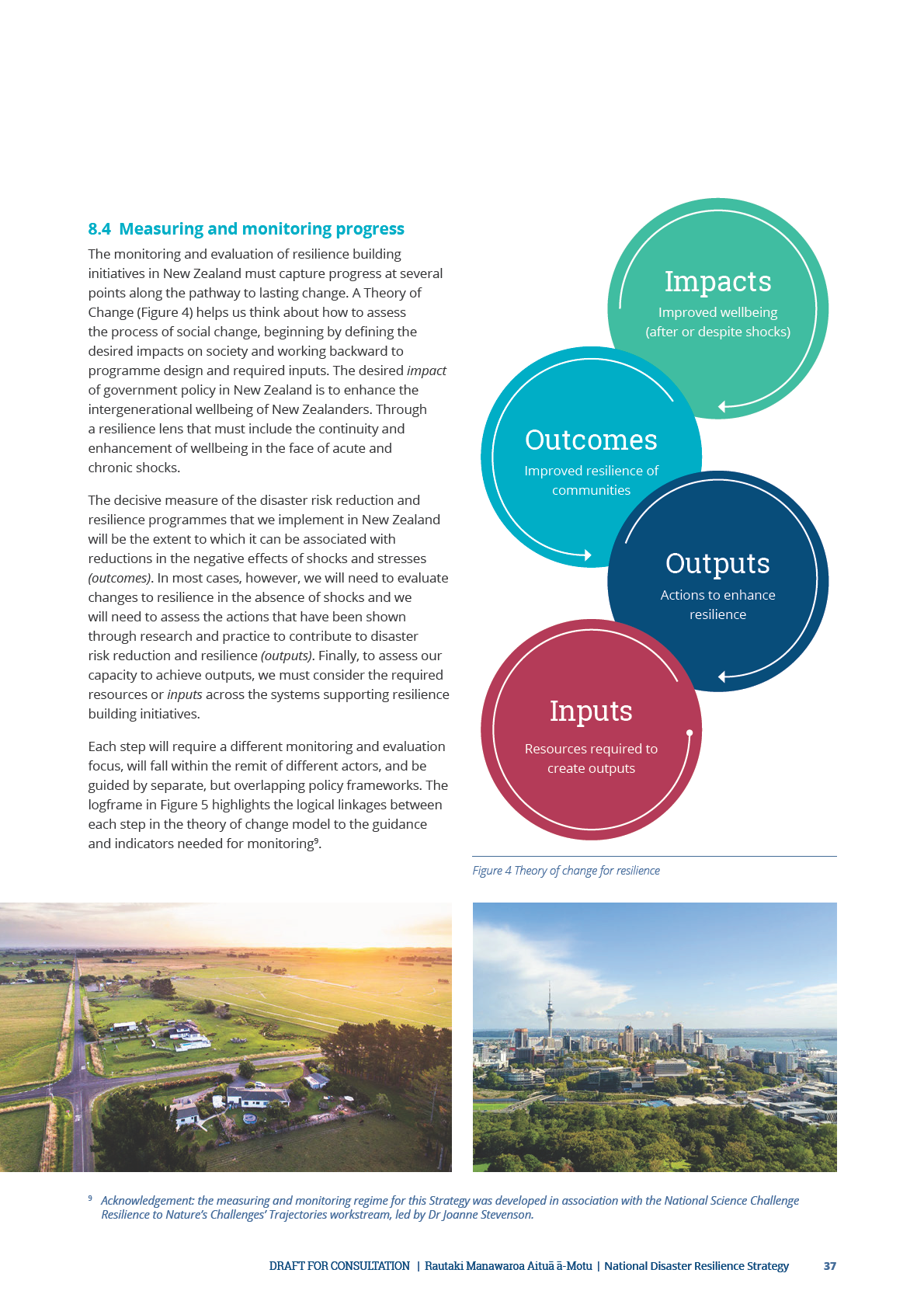

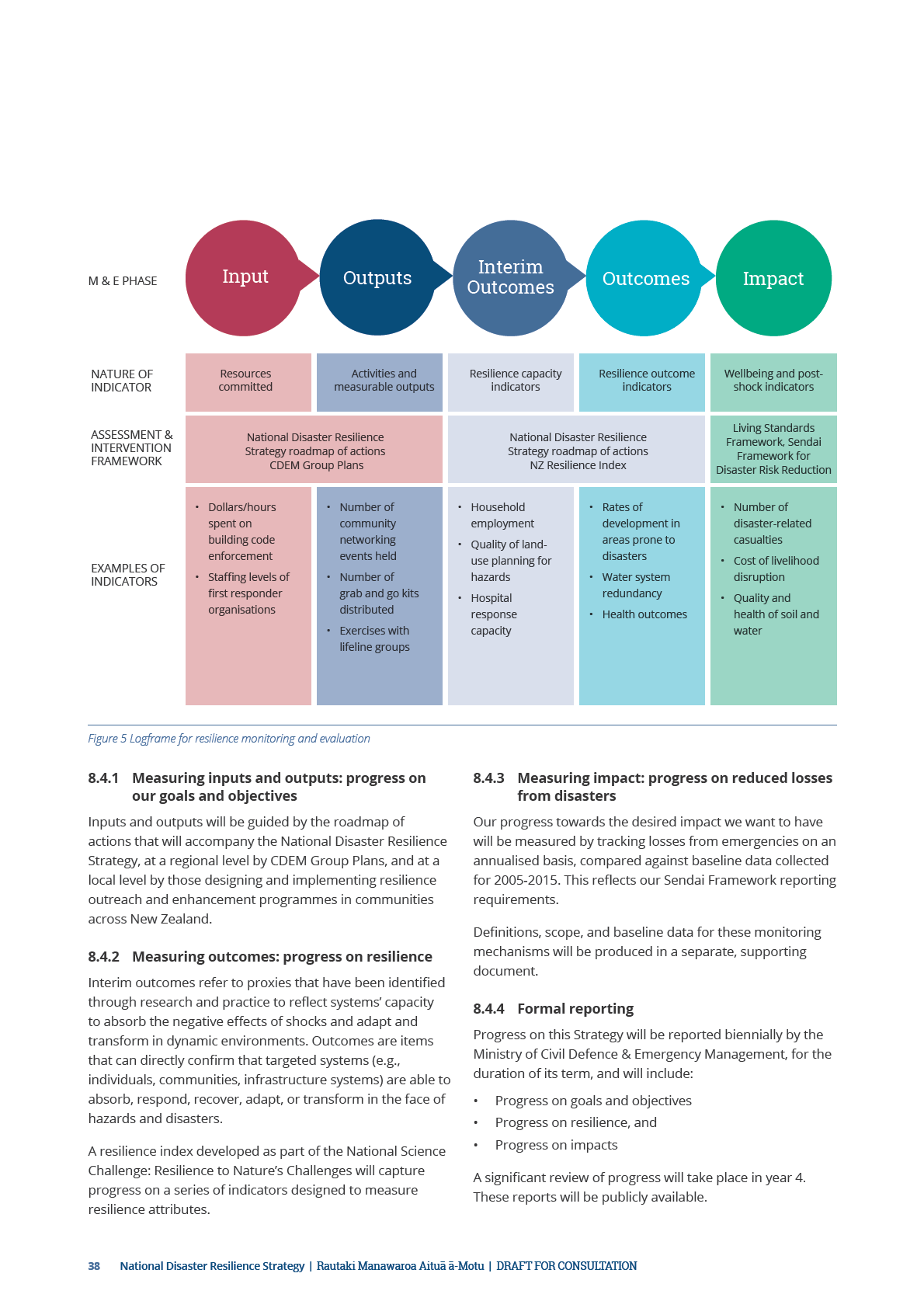

The process to develop a roadmap of actions will include

It is envisaged that this can be achieved in three main ways:

work to identify practical ways to strengthen the voice and

a principle of transparency and social accountability, formal

capacity of all stakeholders, including the public, and those

governance mechanisms, and measuring and monitoring

disproportionately affected by disasters.

progress.

8.2 Transparency and social accountability

Released

It is critical that we are transparent about both our risks

and our capacity to manage them. It is only by exposing the

issues and having open conversations that we will make

progress on overcoming barriers, and build on strengths

and opportunities.

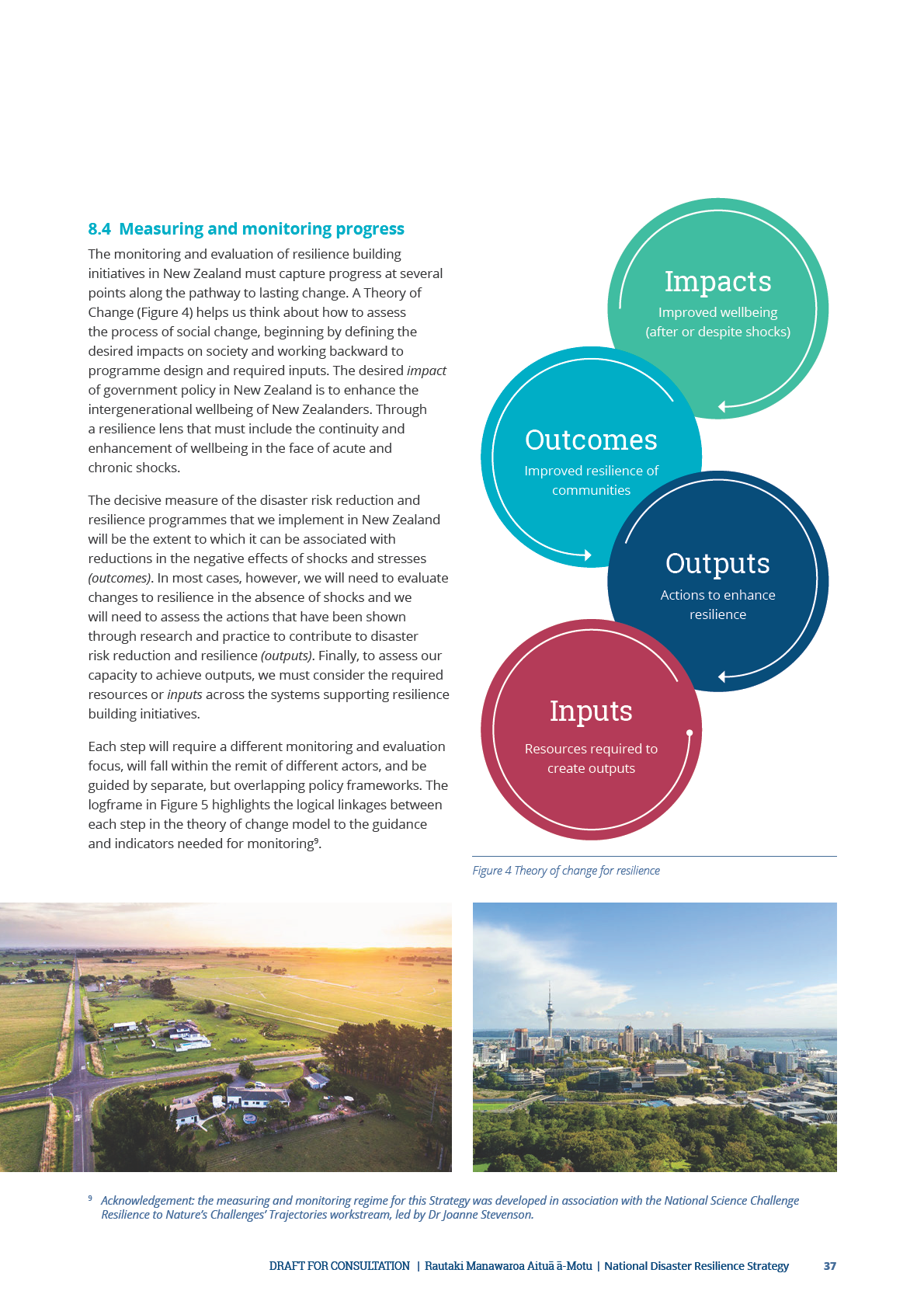

36 National Disaster Resilience Strategy | Rautaki Manawaroa Aituā ā-Motu | DRAFT FOR CONSULTATION

under the Official Information Act 1982

Released

under the Official Information Act 1982

Released

under the Official Information Act 1982

Released

under the Official Information Act 1982

Released

under the Official Information Act 1982

Released

under the Official Information Act 1982

Released

under the Official Information Act 1982

Released

under the Official Information Act 1982

Released

under the Official Information Act 1982

Released

Appendix 2: Analysis of our current state as

a baseline for this Strategy

In order to form an effective strategy for the future and move towards a state of enhanced resilience, it is useful to look at

our current state – our strengths, barriers, and opportunities – and how we capitalise on areas of strength and opportunity,

overcome obstacles to progress, and make the smartest possible choices about actions and investment. Furthermore, in the

quest to be ‘future ready’, it is useful to consider what other environmental and societal trends are occurring around us, even

now, and how we can use them to build our resilience.

Strengths

New Zealand already has a number of strengths in respect

risk management, including the CDEM Act 2002, the

of disaster resilience.

Resource Management Act 1991, the Building Act 2004,

the Local Government Act 2002, and a range of other

1. We have good social capital in our communities. New

legislation and regulatory instruments. This includes

Zealand communities are aware, knowledgeable,

regulation for land-use and building standards – critical

passionate, and well-connected. In general, they have

factors in building more resilient futures.

a strong sense of local identity and belonging to their

8. We have an effective national security coordination

environment, a belief in manaakitanga and concern for

system that takes an all-hazards approach and has

their fellow citizens, and a sense of civic duty.

governance at the political, executive, and operational

2. We are a developed country that has comprehensive

levels.

education, health, and social welfare systems, which

9. At the regional level consortia of local authorities,

build our people and look after the most vulnerable

emergency services, lifeline utilities, and social welfare

in society.

agencies (government and non-government) form CDEM

3. We have a strong cultural identity, including the special

Groups that coordinate across agencies and steward

relationship between Māori and the Crown provided

emergency management in their regions.

through the Treaty of Waitangi. New Zealand is also

10. We have an engaged and well connected science

one of a handful of culturally and linguistically ‘super-

community, including a number of platforms specifically

diverse’ countries, which brings a number of economic

targeting the advancement of knowledge and

and social benefits, and expanded knowledge and

understanding about natural hazards and resilience.

experience (the ‘diversity dividend’). We value our

In general, there are good links between scientists,

culture, our kaupapa and tikanga. We celebrate and

policy makers and practitioners. Scientists practice an

foster a rich and diverse cultural life.

increasing level of community outreach, engage in a

4. We have a high-performing and relatively stable

co-creation approach, and are focussed on outcomes.

economy. The New Zealand economy made a solid

11. Organisations and agencies work well together. While

recovery after the 2008-09 recession, which was shallow

there’s always room for improvement, a multi-agency

under the Official Information Act 1982

compared to other advanced economies. Annual growth

approach is the ‘norm’, which means better coordination

has averaged 2.1% since March 2010, emphasising the

of activities, more efficient use of resources, and better

economy’s resilience.

outcomes.

5. We have very high insurance penetration across

12. We are a small country, which makes us well-connected,

residential property. Most countries struggle to get their

uncomplicated, and agile. We can ‘get things done’ in

ratio of insured to non-insured up to an acceptable level.

relatively short order.

Because of the Earthquake Commission, New Zealand’s

13. We are experienced. We have seemingly had more than

residential insurance penetration is 98%. This means

our fair share of crises, emergencies, and disasters over

that a good proportion of the economic costs of most

Released

the last ten years. This has brought some bad times,

natural hazard events are covered by re-insurance.

but the silver lining is the awareness that it has built in

6. We have a stable political system, low levels of

everyone, the knowledge about ‘what works’ and what is

corruption, and freedom of speech.

needed, and the willingness to act.

7. We have a good range of policy in place for disaster

46 National Disaster Resilience Strategy | Rautaki Manawaroa Aituā ā-Motu | DRAFT FOR CONSULTATION

Barriers to resilience

While we have a lot going for us, we also have some things that limit our resilience. The process to develop this Strategy

identified a number of barriers to resilience, and barriers to our pursuit of resilience.

What is limiting our resilience?

What is limiting our pursuit of resilience?

1. Some of our people still suffer considerable poverty,

1. Not enough people and organisations are taking action

social deprivation, and/or health issues that limit

to prepare or build their resilience for disasters. This is

wellbeing, quality of life, and resilience.

generally either because it is seen as too expensive or

2. Our level of individual and household preparedness for

difficult, because of other priorities, because it ‘might

emergencies (including preparedness for our animals) is

never happen’, or because of an expectation of a rapid

not as high as it should be, given our risks.

and comprehensive institutional response.

3. Our businesses and organisations (including those

2. Building community resilience – even where playing a

involving animals) are not as prepared as they could

facilitative role – is resource intensive. It also requires a

be, leading to loss of service and losses in the economy

high level of skill and understanding to navigate diverse

when severe disruption strikes.

communities and complex issues.

4. Some of our critical assets and services are ageing and

3. Emergency management issues tend to be ‘headline’

vulnerable. These are in most places being addressed

issues that require immediate corrective action. This is

by asset management plans and asset renewal

understandable, and needed, but means we often focus

programmes, (including strengthening, conservation

more on fixing the problems of the day, and addressing

and restoration), but these will take time (and resources)

issues from the last event, than forecasting the future

to implement.

and taking action for the long-term.

5. We live in some high-risk areas, and are continuing to

4. Risk reduction and resilience are often perceived as

build in high-risk areas – particularly around the coast,

‘expensive’, and limiting of economic development and

on steep slopes, fault lines, reclaimed land, and flood

business growth.

plains. We live and build there because they are nice

5. At the same time, the full cost of disasters often isn’t

places to live, and because sometimes there is no other

visible (particularly the cost of indirect and intangible

choice. However, insurance in these areas may some

impacts, including social and cultural impacts), meaning

day become unaffordable. At some point we need to

it isn’t factored into investment decision-making.

consider – for ourselves, our communities, and for

6. Perverse incentives don’t encourage resilience – too

future generations – how much risk is too much?

often, as a society, we are aiming for the ‘minimum’

6. We are only just starting to tackle some of the ‘truly

standard or ‘lowest cost’. This can deter people from

hard’ issues around existing levels of risk, such as how to

aiming higher or for the ‘most resilient’ solution.

adapt to or retreat from the highest risk areas, including

under the Official Information Act 1982

7. Recovery is often underestimated. The Christchurch

to adapt to the impacts of climate change. There is likely

earthquake recovery and many other smaller events

high cost around many of these options.

have shown us just how complex, multi-faceted, difficult,

7. We have gaps in our response capability and capacity,

expensive, and long-term recovery is. Other parts of

as outlined in a recent Ministerial Review into better

the country need to consider how they would manage

responses to emergencies in New Zealand (Technical

recovery in their city or district, and give priority to

Advisory Group report, 2017). These are predominantly

resourcing capability and capacity improvements.

around capability of individuals, capacity of response

8. We have had difficulty translating resilience theory into

organisations, and powers and authorities of those

action. There is an abundance of academic theory on

individuals and organisations to act. The review also

Released

resilience, but turning that theory into practical action

identified issues with communication and technology, in

has, until recently anyway, been difficult to come by.

particular, the challenges of response intelligence and

communications staying apace with social media.

DRAFT FOR CONSULTATION | Rautaki Manawaroa Aituā ā-Motu |

National Disaster Resilience Strategy 47

Opportunities

As well as strengths and barriers, it is important to consider what opportunities we have or may have on the horizon. The

opportunities the strategy development process has identified are:

1. Awareness and understanding of disasters, disaster

7. The Government has a strong focus on wellbeing,

impacts and disaster risk, is at an all-time high following

particularly intergenerational wellbeing, and

a series of domestic events over the last 5-10 years,

improved living standards for all. Simultaneously,

including the Canterbury and Kaikōura earthquakes.

local government has a renewed interest in the ‘four

This includes a willingness to act on lessons and to do so

wellbeings’ with those concepts being re-introduced

in a smart, coordinated, and collaborative way.

to the Local Government Act as a key role of local

2. Our hazards are obvious and manifest. This is both a

government. These priorities are entirely harmonious,

curse and an opportunity: we have high risk, but we also

and lead swiftly into a conversation with both levels

have an awareness, understanding, and willingness to

of government on how to protect and enhance living

do something about them, in a way that countries with

standards through a risk management and resilience

less tangible risks might not. If we address risk and build

approach.

resilience to our ‘expected’ hazards, we will hopefully

8. We have only just begun to scratch the surface of best

be better prepared for when the ‘less expected’

resilience practice, including how to make the most of

hazards occur.

investment in resilience. There is much to learn from the

3. We have an incredible wealth of resilience-related

Triple Dividend of Resilience [see page 51] – ensuring

research currently underway, including several multi-

our investments provide multiple benefits or meet

sectoral research platforms that aim to bring increased

multiple needs, and are the smartest possible use of

knowledge to and improved resilience outcomes for

limited resources. The Triple Dividend also supports

New Zealanders. Over the next few years there will be

better business cases, allowing us to better position our

a steady stream of information about ‘what works’, and

case for resilience and convince decision-makers of the

tried and tested methodologies we can employ in all

benefits of investment.

parts of society.

9. We are a small agile nation. We are ambitious,

4. We also have a lot of other work – in terms of resilience-

innovative, motivated, and informed: we can lead the

related policy and practice – underway in organisations

world in our approach to resilience.

at all levels and across the country. Connecting the

pieces of the jigsaw, sharing knowledge, and working

together should enable even more improved outcomes.

5. There is a particular opportunity for building processes

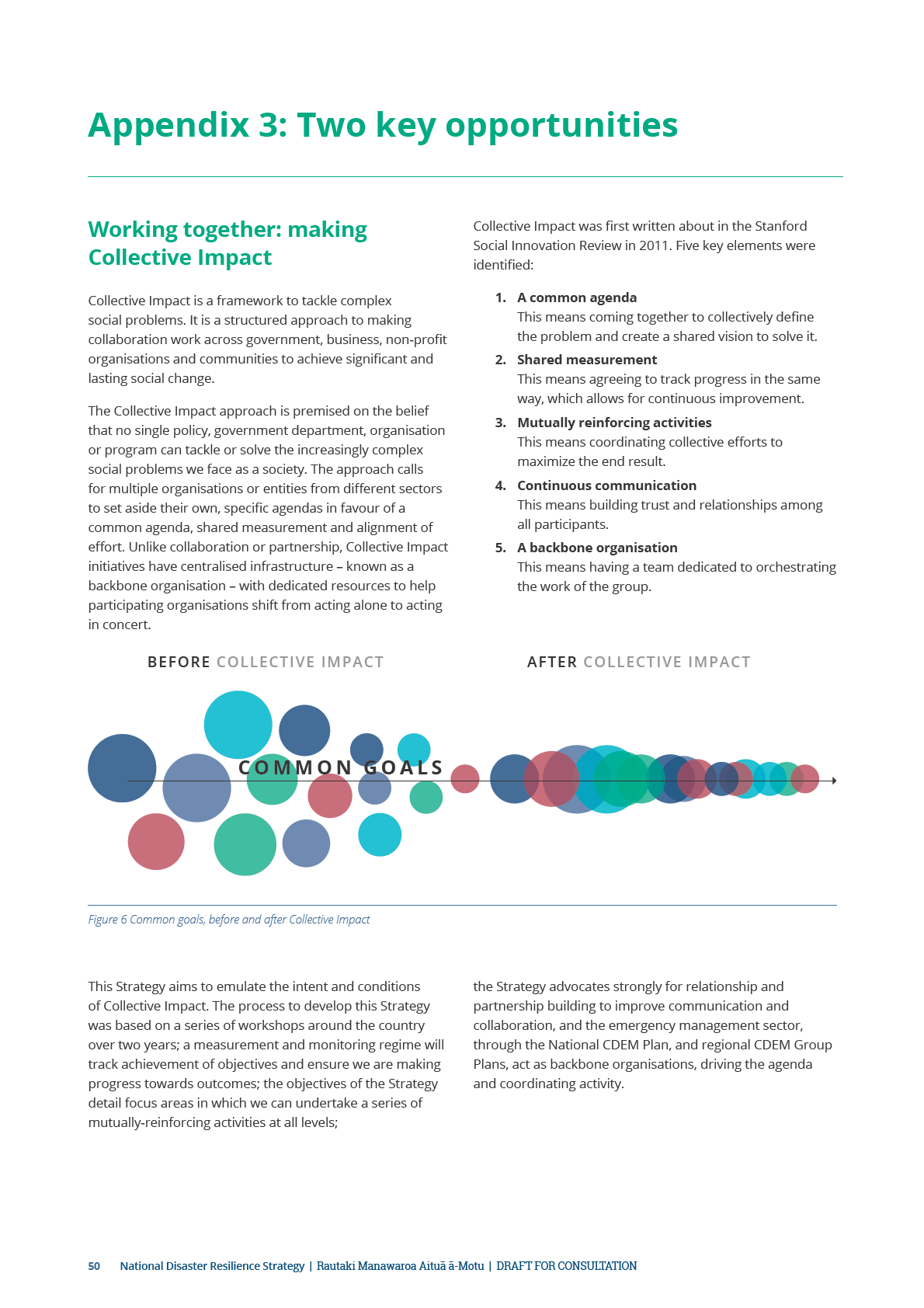

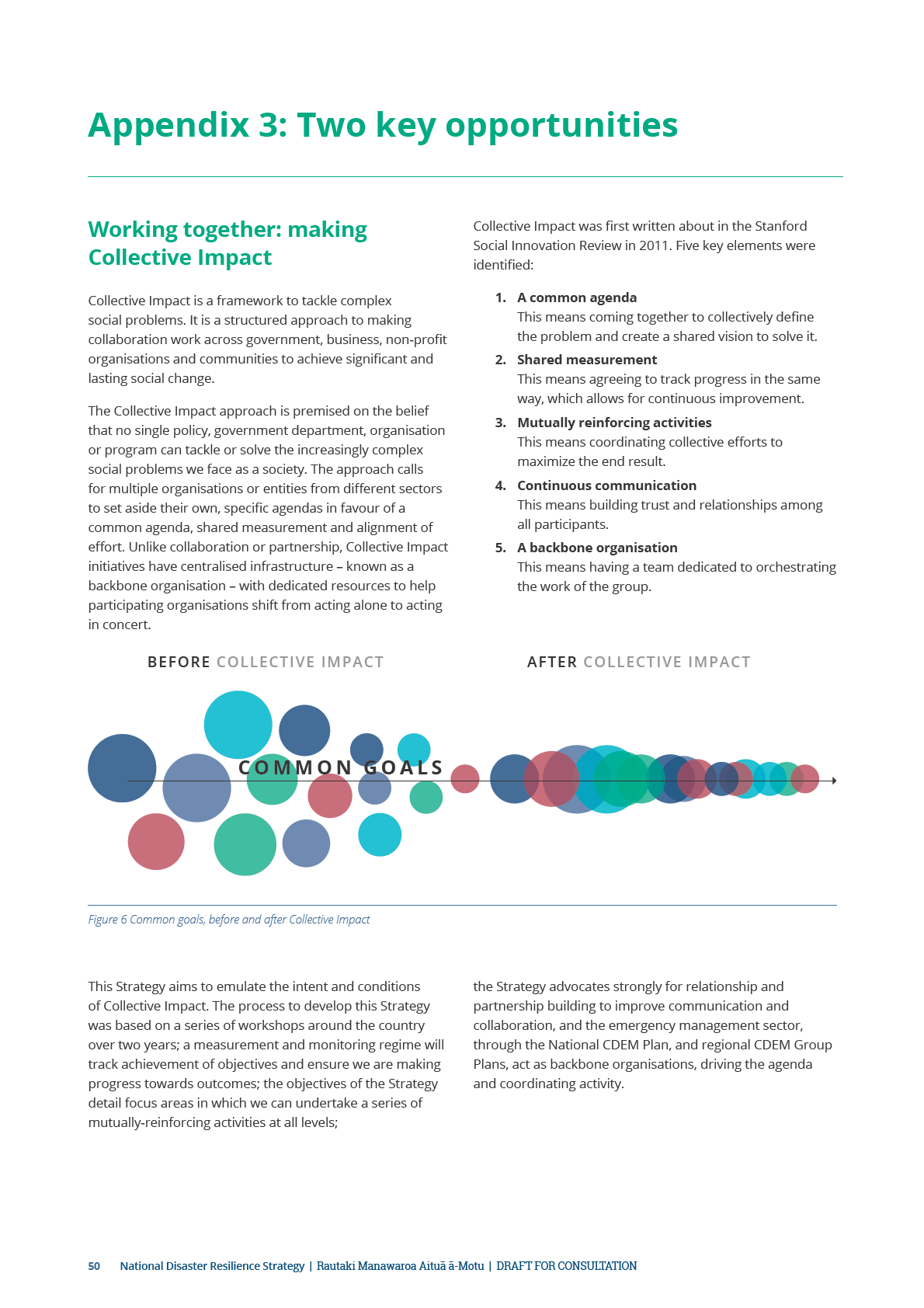

that support collective impact. Collective Impact is a

under the Official Information Act 1982

way of organising a range of stakeholders around a

common agenda, goals, measurement, activity, and

communications to make progress on complex societal

challenges. [see page 50]

6. The introduction of the three post-2015 development

agendas (Sendai Framework, Sustainable Development

Goals, and Paris Agreement for Climate Change) brings

an additional impetus and drive for action, as well as

practical recommendations that we can implement.

Released

They also bring a strong message about integration,

collaboration, and a whole-of-society approach.

48 National Disaster Resilience Strategy | Rautaki Manawaroa Aituā ā-Motu | DRAFT FOR CONSULTATION

‘Wild cards’

The world is changing at an unprecedented rate driven by technical innovation and new ways of thinking that will

fundamentally transform the way we live. As we move away from the old structures and processes that shaped our past,

a new world of challenges and opportunities awaits us. While there might be uncertainty about how some of these factors

might shape our risk and our capacity to manage that risk, there are some common implications that are critical to take

account of as we work to build resilience.

1. The revolution in technology and communication is a

5. High levels of trust across organisations, sectors and

key feature of today’s world. Regardless of the issue,

generations will become increasingly important as a

technology is reshaping how individuals relate to one

precondition for influence and engagement. This trust

another. It shifts power to individuals and common

will need to be based on more than just the existence of

interest groups, and enables new roles to be played

regulations and incentives that encourage compliance.

with greater impact. Organisations and groups that

Organisations can build trust among stakeholders

can anticipate and harness changing social uses of

via a combination of “radical transparency” and by

technology for meaningful engagement with societal

demonstrating a set of social values that drive behaviour

challenges will be more resilient in the future.

that demonstrates an acknowledgement of the

common good.

2. Local organisations and grassroots engagement is an

important component. This is driven in part by the

6. The possibility of new and innovative partnerships

aforementioned technology and communication shifts

between government, the private and not-for-profit

that give local groups more influence and lower their

sectors, may provide new platforms for positive change.

costs for organising and accessing funding, but also

The challenge of disaster risk can no longer be the

the rising power of populations in driving actions and

domain of government alone. A collective approach is

outcomes.

needed, including to utilise all resources, public and

private, available to us, and to consider innovative

3. Following on from these, populations currently under

approaches to managing and reducing risk. This

the age of 30 will be a dominant force in the coming two

requires active participation on the part of the private

decades – both virtually, in terms of their levels of online

sector, and transparency, openness, and responsiveness

engagement, and physically, by being a critical source of

on the part of politicians and public officials.

activity. Younger generations possess significant energy

and global perspectives that need to be harnessed for

7. The need for higher levels of accountability,

positive change.

transparency, and measurement. More work is required

to ensure that those tackling societal challenges have

4. The role of culture as a major driver in society, and

the appropriate means of measuring impact. These

one that desperately needs to be better understood

mechanisms will need to be technology-enabled,

by leaders across governments, the private sector, and

under the Official Information Act 1982

customised to the challenge at hand, and transparent.

civil society. Culture is a powerful force that can play a

significant role (both positive and negative, if it is not

handled sensitively), and is therefore a force with which

stakeholders should prepare to constructively engage.

Released

DRAFT FOR CONSULTATION | Rautaki Manawaroa Aituā ā-Motu |

National Disaster Resilience Strategy 49

under the Official Information Act 1982

Released

Changing the narrative:

However, there is increasing evidence that building

the Triple Dividend of Resilience

resilience yields significant and tangible benefits, even if a

disaster does not happen for many years – or ever.

In New Zealand we have first-hand, recent examples of

A 2015 report outlines the ‘Triple Dividend of Resilience’, or

how much disasters can cost. The direct costs alone can

the three types of benefits that investments in disaster risk

be significant; as we start to consider methodologies for

management can yield. They are:

counting the economic cost of social impact, the total cost of

1. Avoiding losses when disasters strike

disasters and disruptive events will be significantly more –

maybe even double the reported ‘direct’ costs.

2. Stimulating economic activity thanks to reduced

disaster risk, and

Even so, it is often difficult to make a case for investment

3. Generating societal co-benefits.

in disaster risk management and resilience, even as we cite

research on benefit-cost ratios – how upfront investment in

While the first dividend is the most common motivation

risk management can save millions in future costs. We know

for investing in resilience, the second and third dividends

these ratios to be true, we have seen examples of it, even

are typically overlooked. The report presents evidence that

here in New Zealand, so why is it such a hard case to make?

by actively addressing risk, there can be immediate and

significant economic benefits to households, the private

Other than short-term political and management cycles,

sector, and, more broadly, at the macro-economic level.

it is generally due to how we calculate ‘value’. Traditional

Moreover, integrating multi-purpose designs into resilience

methods of appraising investments in disaster risk

investments can both save costs, and provide community

management undervalue the benefits associated with

and other social benefits (for example, strengthened flood

resilience. This is linked to the perception that investing

protections works that act as pedestrian walkways, parks

in disaster resilience will only yield benefits once disaster

or roads).

strikes, leading decision-makers to view disaster risk

management investments as a gamble that only pays off

New Zealand needs to learn from this concept and ensure that

in the event of a disaster – a ‘sunk’ cost, that gives them no

our investments in resilience are providing multiple benefits to

short-term benefit.

both make smart use of our limited resources, and to assure

decision-makers that their investment is worthwhile, and will

pay dividends – in the short and long term.

1st Dividend of Resilience: Avoided Losses

Increased resilience reduces disaster losses by:

Benefits

1ST OBJECTIVE

1. Saving lives

when

2. Reducing infrastructure damage

diasters

3. Reducing economic losses

strikes

under the Official Information Act 1982

INVESTMENTS IN

2nd Dividend of Resilience: Economic Development

DISASTER RISK

Increased resilience unlocks suppressed economic

MANAGEMENT

2ND OBJECTIVE

potential and stimulates economic activity by:

AND RESILIENCE

1. Encouraging households to save and build assets

2. Promoting entrepeneurship

Benefits

3. Stimulating businesses to invest and innovate

regardless

of disaster

Released

3rd Dividend of Resilience: Co-benefits

3RD OBJECTIVE

Beyond increasing resilience, disaster risk management

investment also yields positive social, cultural, and

environmental side-benefits (‘co-benefits’)

Figure 7 The Triple Dividend of Resilience Investment – Adapted from: The Triple Dividend of Resilience – Realising development goals through the multiple

benefits of disaster risk management (Global Facility for Disaster Reduction and Recovery, the World Bank, Overseas Development Institute, 2015).

DRAFT FOR CONSULTATION | Rautaki Manawaroa Aituā ā-Motu |

National Disaster Resilience Strategy

51

under the Official Information Act 1982

Released

Item 5: Draft Cabinet Paper National Disaster Resilience Strategy: Approval and Presentation to the House

under the Official Information Act 1982

Released

under the Official Information Act 1982

Released

under the Official Information Act 1982

Released

under the Official Information Act 1982

Released

under the Official Information Act 1982

Released

under the Official Information Act 1982

Released

under the Official Information Act 1982

Released

under the Official Information Act 1982

Released

Item 6: Briefing: No Animal Left Behind: A Report on Animal Inclusive Emergency Management Law Reform

under the Official Information Act 1982

Released

under the Official Information Act 1982

Released

under the Official Information Act 1982

Released

under the Official Information Act 1982

Released

under the Official Information Act 1982

Released

under the Official Information Act 1982

Released

under the Official Information Act 1982

Released

under the Official Information Act 1982

Released

under the Official Information Act 1982

Released

under the Official Information Act 1982

Released

Item 7: Email Chain: Prep for GAC hearing on National Disaster Resilience Strategy

under the Official Information Act 1982

Released

From: Kate Littin s9(2)(a)

>

Sent: Tuesday, 5 March 2019 5:16 PM

To: Alex Hogg [DPMC] <s9(2)(a)

; Anthony Richards [DPMC] s9(2)(a)

Cc: Wayne Ricketts s9(2)(a)

Subject: FW: Prep for GAC hearing on National Disaster Resilience Strategy

Hi both

Thought it might be helpful to share these before we meet in the morning

Talking points – can discuss tomorrow

We also summarised our thoughts on the key recommendations in No Animal Left Behind, in case these points are

raised tomorrow

We’ve not yet worked our way through all of the submissions but will do so before we meet.

See you tomorrow

Kate & Wayne

Kate Littin PhD | Manager Animal Welfare Team

Animal Health & Welfare | Regulation & Assurance Branch

Ministry for Primary Industries | Pastoral House 25 The Terrace | PO Box 2526 | Wellington | New Zealand

Telephone: s9(2)(a)

| MPI tel: 0800 00 83 33 | Mobile: s9(2)(a)

Web: www.mpi.govt.nz

Follow MPI on Twitter (@MPI_NZ) and Facebook

SEEMAIL

__________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

This email message and any attachment(s) is intended solely for the addressee(s)

named above. The information it contains may be classified and may be legally

under the Official Information Act 1982

privileged. Unauthorised use of the message, or the information it contains,

may be unlawful. If you have received this message by mistake please call the

sender immediately on 64 4 8940100 or notify us by return email and erase the

original message and attachments. Thank you.

The Ministry for Primary Industries accepts no responsibility for changes

made to this email or to any attachments after transmission from the office.

__________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Released

1

MPI talking points – GAC National Disaster Resilience hearing 6 March 2019

Key points

• We note a number of submissions raise points about animal welfare, including that the draft

National Disaster Resilience Strategy should explicitly refer to animals more, and incorporate

a new objective for reform of emergency management.

• This is a high level strategy which already incorporates responsibilities towards animals in

several aspects. This includes referring to saving animal lives in the definition of ‘response’,

and reminders in the document for emergency management plans to include animals.

• In general, the concerns raised in the submissions can be addressed in the work that will

happen under the strategy, and in other local and central government work on emergency

management readiness, response and recovery.

• We don’t believe it hampers forward progress in animal welfare by NOT having a greater

focus on, animal welfare in the draft strategy.

• We believe the outcomes that the submitters are hoping to achieve are able to be achieved

under the draft strategy and under the work programmes already underway to progress

emergency management and animal welfare in emergencies.

Achievements to progress animal welfare to date

• A key achievement that has promoted animal welfare was the legislative change in 2015 that

saw animal welfare recognized as a subfunction of Welfare in the National Civil Defence and

Emergency Management Plan which reflects the role of animals in our society.

• Since then, we see an increased acceptance amongst the CDEM community of the need to

consider animal wel being alongside human and community wel being, supporting the

expectations of New Zealanders that their animals will be taken into account in responses

and recovery. Both of these aspects are best il ustrated by the recent response to the Nelson

Tasman fire, where arrangements were in place for animals to be evacuated, a system was

set up by MPI with support agencies to fol ow up on animals that needed to be left behind,

and animal owners were permitted restricted access to tend their animals where they had

not been evacuated.

• This is supported by good interagency relationships and systems established at central

under the Official Information Act 1982

government level, at a regional level and between MPI and our support agencies.

• New Zealand’s framework for animal welfare in emergency management is considered

world leading, as evidenced by calls for New Zealand to contribute to the development of

policy and research and work programmes overseas.

Work programmes underway

Released

• Planned legislative review being led by MCDEM – MPI is contributing;

• Work programmes to address points raised from previous responses, including the No

Animal Left Behind report, the published outcomes of the Port Hills fires, and lessons

learned from the Kaikoura earthquake, the Edgecumbe flood and experiences from the

recent Nelson/Tasman fire.

• These are being incorporated into MPI’s (the responsible agency for animal welfare in

emergency) workplan and include:

o

Completing regional animal welfare in emergency plans for all 16 regions

o

Developing a regional coordination system

o

Socialising the importance of animal welfare with Civil Defence Groups, and agencies

such as Police, Fire and Emergency NZ, Ministry of Health (in regards to

psychosocial support when animals die/lost/euthanased)

o

Developing information for dealing with animals in different sorts of disasters

o

Considering the development of a nationwide animal rescue capability

o

Responding to animal welfare needs in an emergency – the latest being the Nelson

fire

• There is a gap in who pays for animal welfare in emergencies – both the CDEM Act and

Animal Welfare Act are silent. We are looking at ways how this could be funded – both

legislative and by policy.

• MPI has become a respected responsible agency and the CDEM sector has confidence that

MPI will and does carry out its responsibilities for animal welfare in emergencies.

Background

• DPMC consulted on a draft National Disaster Resilience Strategy last year. MPI made a

submission that supported the Strategy – this was coordinated out of the Readiness team

(BioNZ).

• The Strategy is currently in front of the GAC, to recommend for issue in April. The current

strategy expires 9 April. The strategy is reasonably high level.

• The GAC invited public submissions on the draft strategy in February. Animal Evac

encouraged submissions with content on better incorporating animals into planning, rescue

and recovery at a national level (http://www.animalevac.nz/strategyconsult/ ). We were

unaware of this webpage.

• DPMC reported that the Committee received more than 100 submissions on animal welfare

(of a total of approx. 160). The Animal Evac page encourages reference to the No Animal Left

Behind report. We have initial views on the recommendations in that report.

• The GAC is the select committee that considers civil defence and emergency management

matters. It is chaired by Brett Hudson, National List MP and has a mix of Labour and National

members. Animal Evac is normally supported by Gareth Hughes MP.

• Separately, MCDEM (Ministry for Civil Defence and Emergency Management, part of DPMC)

is writing to Steve Glassey to acknowledge his No Animal Left Behind report, and Minister

Faafoi is writing to Gareth Hughes to thank him for sharing Steve Glassey’s No Animal Left

under the Official Information Act 1982

Behind report, and indicating that MCDEM will work with MPI on the recommendations as it

sees fit.

Released

Notes on key recommendations in No Animal Left Behind

Kate Littin, 4 March 2019

Key recommendation from No Animal Left Behind

MPI initial response

1. The need for companion animal emergency To discuss with CDEM; current animal

management to be led by traditionally human welfare sits as a sub-function of

focused agencies, such as the Ministry of Civil Welfare, which is focussed on human

Defence & Emergency Management at the welfare. This appears to achieve the

national level, and Civil Defence Emergency outcome that is recommended here.

Management Groups at the regional level, as

companion animal emergency management

should be fully integrated with human focused

emergency management as the two were

intrinsically linked.

2. That MPI to be responsible for non-companion We are.

animals such as livestock, factory farms, zoos,

aquariums, and research facilities.

3. A lack of national animal specific emergency Not too sure what the issue is here;

management plans and where plans had been regional plans have ‘legal status’. There

completed at the regional level they had not are regional plans completed or

been afforded any legal status making them underway for all 16 regions, supported

unenforceable.

by MPI.

4. That emergency management laws be We are investigating various legal

expanded to ensure the range of emergency powers with MPI Legal. This is a

powers could also be used for the protection of significant and complex issue and

animals, including adding microchipping of involves powers under a number of

animals as an emergency power.

different Acts.

5. Providing clear mandate for the rescue and We consider this is best addressed

under the Official Information Act 1982

decontamination of animals, and that such under regional CDEM plans (the

operations fall under Fire & Emergency New specifics) and at a national level by work

Zealand, to ensure human and animal rescue we are doing with FENZ. We consider

operations were better integrated.

that there is a role for agencies other

than FENZ (eg Police).

6. Emergency response and training funding for We agree wholeheartedly; we are

animal welfare be made available, rather than waiting on MPI Legal advice on some

Released

having the good will of animal charities be specific aspects, and have been working

exploited.

with MCDEM on funding for training.

7. That the two national microchipping database This is a specific point that can be picked

are enabled to share data, in particular during up at a regional level in regional plans,

emergencies to ensure improved reunification but requires agreement to at a national

rates.

level by individual CDEM groups – which

has previously not been agreed.

8. Creating an offence for placing service dog A specific point we are considering for

identification on dogs that are not certified as our work programme.

disability assistance dogs; and another offence

for failing to protect animals from hazards such

as floods, fires etc where it is reasonable to do

so.

9. Ensuring commercial operators of animal Agree. Requirements for contingency

housing facilities have documented emergency planning are laid out in the code of

management plans in place that are tested.

welfare for temporary housing, issued

under the Animal Welfare Act in 2018.

10. That local authorities need to ensure they have Agree in principle that this may be

provisions in their bylaws to allow for necessary – to be considered whether

emergency

variations

to

dog

control MPI needs to do anything specific about

ordinances such as designating emergency dog this recommendation.

exercise areas.

11. That the legal processes for entry onto For MCDEM consideration.

property to carry out rescue of animals,

including seizure, notification to owners and

disposal, including rehoming be amended as

the current laws fail to provide for rehoming of

animals seized under civil defence legislation as

disposal provisions were omitted.

12. That the National Animal Welfare Advisory NAWAC can have specific expertise in

Committee expand their prescribed expertise this regard if necessary; it has previously

to including animal disaster management given received this advice from external

the demands of climate change.

consultants and a national board

(NAWEM). We do not agree that this

should be a statutory requirement.

13. That following a disaster in the statutory For MCDEM and regional CDEM plans.

under the Official Information Act 1982

recovery transition period, those seeking rental

accommodation cannot be discriminated

against for owning companion animals to

ensure the family unit can remain together.

14. That civil defence no longer have the This needs to be worked through with

autonomous power to destroy animals in a MCDEM; we are not sure this is

Released

disaster, with new requirements to consult necessary, although would agree with

with an animal welfare inspector should this the outcome that appropriate decisions

option be pursued.

are made and that euthanasia is carried

out in accordance with the Animal

Welfare Act.

15. That a new Code of Emergency Welfare be The National Animal Welfare Advisory

introduced to provide minimum standards for Committee will be advised of this

animals during times of emergencies as recommendation (at the moment, it is

standard Codes of Welfare often are not aware of the recommendation but has

enforceable during times of emergency.

not received advice on it from MPI).

16. That animal population data is developed and Agree. MPI has this on its 2018/19 and

maintained for emergency planning purposes.

2019/20 work programme.

17. That companion animals be permitted on Presumably civil defence powers can allow

public transport to aid their evacuation during this. MCDEM will need to consider this

emergencies.

recommendation.

under the Official Information Act 1982

Released

Item 8: Email Chain: Subs Summary for GAC 6 March

under the Official Information Act 1982

Released

From: Kate Littin s9(2)(a)

>

Sent: Wednesday, 6 March 2019 2:11 PM

To: Anthony Richards [DPMC] <s9(2)(a)

Subject: Fwd: Subs summary GAC 6 March

As discussed

Sent from my iPhone ‐ please excuse brevity

Begin forwarded message:

From: Kate Littin s9(2)(a)

>

Date: 6 March 2019 at 7:32:07 AM NZDT

To: Wayne Ricketts s9(2)(a)

>, Chris Rodwell <s9(2)(a)

>

Subject: Subs summary GAC 6 March

Morning

My notes attached on submissions to GAC on the draft National Resilience Strategy – to discuss

today

Wayne – be keen to hear your thoughts on SPCA sub this morning

Kate

Kate Littin PhD | Manager Animal Welfare Team

Animal Health & Welfare | Regulation & Assurance Branch

Ministry for Primary Industries | Pastoral House 25 The Terrace | PO Box 2526 | Wellington | New Zealand

Telephone s9(2)(a)

| MPI tel: 0800 00 83 33 | Mobile: s9(2)(a)

| Web: www.mpi.govt.nz

Follow MPI on Twitter (@MPI_NZ) and Facebook

SEEMAIL

under the Official Information Act 1982

__________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

This email message and any attachment(s) is intended solely for the addressee(s)

named above. The information it contains may be classified and may be legally

privileged. Unauthorised use of the message, or the information it contains,

may be unlawful. If you have received this message by mistake please call the

sender immediately on 64 4 8940100 or notify us by return email and erase the

original message and attachments. Thank you.

Released

The Ministry for Primary Industries accepts no responsibility for changes

made to this email or to any attachments after transmission from the office.

__________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

1

In confidence - Doc for internal MPI discussion

AW submissions to GAC Feb 2019

General response

A call needs to be made whether to highlight animals more in the wording of the strategy;

Otherwise the strategy already seems to enable the outcomes that are being sought in the

submissions;

Majority of individual animal welfare subs appear to be made without reading the draft strategy.

Animal Evac recommendations:

• The GAC invited public submissions on the draft strategy in February. Animal Evac

encouraged submissions with content on better incorporating animals into planning, rescue

and recovery at a national level (http://www.animalevac.nz/strategyconsult/ ).

“I/we believe that specific, measurable and accountable objectives to better protect animals in

future emergencies will save human life, as well as that of improving animal welfare in such

events.

Under I/we would like to make the following recommendations:

Specific goals should include implementation of the recommendations made by Animal Evac

NZ’s report on animal disaster management presented at Parliament in January 2019.

An additional section under

4.4 Resilience and people disproportionately affected by

disaster; namely

4.4.5 Animals and Community

People often have strong bonds with their animals which can influence their behaviour in

emergencies. Research and experience show that if animals are not protected during

under the Official Information Act 1982

emergencies that owners will often place themselves at risk to do so. Production animals are a

key element of our economy and losses of such animals has economic and trading reputation

impacts. This strategy commits to enhancing laws and arrangements to better protect animals

from disaster, and by doing so protect human life and contribute to great levels of resilience.

Add Strategy Objective 19:

Implement world leading animal disaster management reform to better protect companion

and production animals in particular, including improvements to laws, funding, plans and

Released

capabilities.”

Summary of submissions on animal welfare

Name

Comments

Response

Carley Ferris

Need specific animal disaster management goals;

Ok but animals can be promoted without this

US has PETS – we need the same;

Need specific, measurable and accountable objectives to better

protect animals to save human and animal lives

Should include implementation of Animal Evac report

Detailed work programme not resilience strategy

recommendations

4.4 Resilience and People – add new section re animals [text

Ok but animals can be promoted without this

provided]

Insert new Strategy Objective 19 [text provided – implement world

Above and this work is underway

leading animal disaster management reform…]

Carole Adamson

Needs explicit recognition of animal link with

individuals/communities/families (eg Nelson fires)

Strategy should consider inclusion of animal welfare and animal

welfare orgs as fundamental components of resilience

HUHA

No specific comments on Resilience Strategy

Julie Duncan

No specific comments on Resilience Strategy

Should include implementation of Animal Evac report

recommendations

Julie Duncan – additional

No specific comments on Resilience Strategy

note

Lisa Praeger

AE recs

Raewyn Cowie

Specific recs to include animal welfare/provisions eg ‘felony’ to

All points possible under current law

abandon animals

SAFE

Verbatim AE recs

under the Official Information Act 1982

Soala Wilson

Have an animal disaster plan

General comment from AE

Vivienne Wright

General comments on including animals

Released

Concern at lack of transparency (presumably relating to comments

about closed consultation)

Wendy Gray

AE recs

SPCA

Specific recommendations to incorporate reference to animals as

Could be used to incorporate some references to

part of society, and explicitly recognise them in planning etc

animals if the Committee wanted to;

Seems like desired outcomes can already be met

under current draft.

Susan Elliott

AE recs

Otago CDEM

‘Planning for animal welfare before, during and after emergencies

must be explicitly embedded in the strategy’

Dog Share Collective

No specific comments but supports community approach in strategy

Ann-Marie Lynch

AE recs

Cathy Bruce

General comments

AE recs

Cheryl Easton

AE recs

Claire Hatfield

Suggests take recs from recent AE report

Jo Spence

AE recs

Joan Oxlee

AE recs

Angelika Sansom

AE recs

Emma Roache

Suggests take recs from recent AE report

Helen McGowan

General comment that animals need to be considered/rescued

Katherine Walsh

AE recs

Manako Sugiyama

AE recs

Maria Gray

General comment that animals need to be considered/rescued

Natasha Parshotam

General comment that animals need to be considered/rescued

Sandra Toomer

General comment that animals need to be considered/rescued

Rose Guscott

General comment that animals need to be considered/rescued

Theresa Parkin

Suggests take recs from recent AE report

under the Official Information Act 1982

Sharon Kirk

AE recs

Emily Brewer

General comment that animals need to be considered/rescued

James Chin

AE recs

Released

Kimberly Schick-

General comment that animals need to be considered/rescued

Puddicombe

Maria Cawdron

General comment that animals need to be considered/rescued –

animals are family too

Nancy Higgins

AE recs

Sandra Munro

General comment that animals need to be considered/rescued

Kia Barnes

General comment that animals need to be considered/rescued

Sarah Lodge

AE recs

Trudy Burgess

AE recs

Animal Evac

SG report No Animal Left Behind

Animal Evac

General comments

Animal Evac

AE recs

Russell Black

General comments to evacuate with animals etc

46 individual subs

General comment that animals need to be considered/rescued

Or AE recs

Glen George

Personal comment/anecdotes from Nelson fires

(Approx 82 total on AW

indiv subs)

(5 organisation subs)

under the Official Information Act 1982

Released