OIA 20-E-0220 – DOC-6280869

OIA 20-E-0220 – DOC-6280869

5 May 2020

[FYI request #12599 email]

Dear Mr. Atkinson

Thank you for your Official Information Act request to the Department of

Conservation, dated 9th April 2020. You requested the following:

A copy of an unpublished DOC correspondence to see if there is any information on

the origins of the current kiwi population on Little Barrier Island and whether that

might explain the number of white kiwi that have hatched at Pukaha/Mt Bruce from

kiwi transferred from Little Barrier Island.

The citation given is as Allendorf, A., Gemmell, N., Ramstad, K., Taylor, H., Weir, J.,

and White, D. 2016. Response to DOC ref: Request for Advice -- Expert Genetic

Advice Regarding the Use of Ponui and Little Barrier Islands as Kiwi Translocation

Founders. Unpublished document DOC-2754937, 1 May 2016.

The correspondence has been released in full and includes the original request from

the department listed in the above citation (Appendix 1 and 2).

As you will note, the original request briefly summarised some of what is known

about the make-up of the founders on Hauturu/Little Barrier Island.

‘It is thought that Hauturu/Little Barrier Island, which now has close to 1000 birds,

was founded by a minimum of 3 western brown kiwi (two transferred in 1902 and

one white bird from the Taupo area released in 1913), perhaps 16 birds of unknown

provenance liberated around 1919, and an unknown number of native Northland-

type birds that had persisted on the island for hundreds or thousands of years. The

latter species was considered extinct in the late 1800s, but Oliver Haddrath has

identified the presence of Northland-type mtDNA in one of 15 samples.’

To expand and slightly correct some of the information included above, brown kiwi

were certainly on Hauturu/Little Barrier Island in the 19th century, and a specimen

collected from there is now in the Vienna Museum. This population was thought to

have died out by the time the two Taranaki birds were introduced in 1902, but given

that the island population has a unique louse not known from mainland populations,

it seems very likely that a few birds remained.

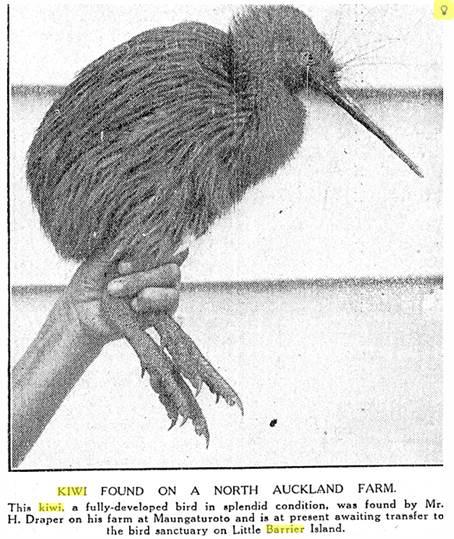

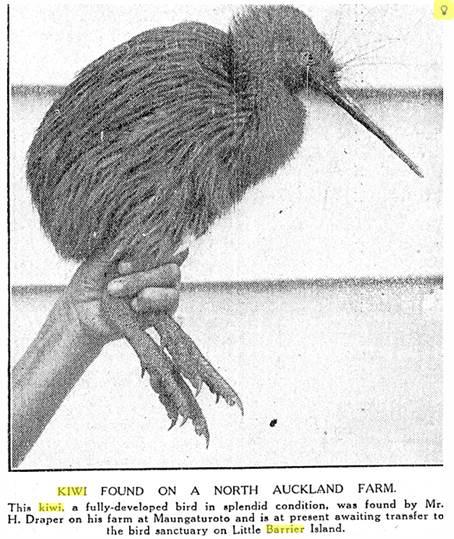

We also believe that birds may have been taken directly from Northland to

Hauturu/Little Barrier Island in the 20th century, such as the bird in this Auckland

Herald

report

of

17

November

1931

(see

“Papers

Past”

website

https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz):

In the Poverty Bay Herald on 11 September 1903 there is a report of a “fine grey kiwi

from Milford Sound” being taken to Hauturu/Little Barrier Island along with four

kakapo from Dusky Sound. This was likely a little spotted kiwi. Whether these birds,

or others, actually got to the island is not known. As an aside, nineteen great spotted

kiwi were also translocated to Hauturu in 1915, but failed.

It seems most likely that the white birds now at Pukaha/Mt Bruce are descendants of

the Taupo bird released in 1913.

We hope this information is useful to you.

Yours sincerely,

Fathima Iftikar

Director – Terrestrial Ecosystems Unit

13th May 2016

Re: Response to DOC ref: Request for Advice – Expert Genetic Advice Regarding the

Use of Ponui and Little Barrier Islands as Kiwi Translocation Founders DOC-

2754937

Signatories: Professor Fred Allendorf, University of Montana, USA

Professor Neil Gemmell, University of Otago, New Zealand

Dr Kristina Ramstad, University of South Carolina, Aiken

Dr Helen Taylor, University of Otago, New Zealand

Dr Jason Weir, University of Toronto, Canada

Dr Daniel White, Landcare Research, Auckland, New Zealand

We have been asked to provide an expert opinion as geneticists on a proposal to use

North Island brown kiwi (

Apteryx mantelli) (NIB) from Hauturu and Ponui Islands to

found or supplement mainland or pest-free island NIB populations.

Our overall message is that the Hauturu and Ponui Island NIB populations have no

genetic value whatsoever for use in restoration due to:

1. the population bottlenecks associated with their founding

2. the genetic admixture within these populations due to their mixed

provenance

Given the known histories of these populations, we are quite confident in these

assertions, even in the absence of genetic data from these sites. To be clear, the

genetic diversity of most or all NIB populations would be reduced by the addition of

Hauturu or Ponui kiwi, likely with harmful effects on population viability. Further,

establishing new populations with Hauturu or Ponui birds would be a poor use of the

few islands and sanctuaries suitable for wild kiwi conservation. A detailed genetic

analysis is unlikely to reveal anything about the Hauturu and Ponui populations that

is not already known (i.e., they each experienced a bottleneck and subsequent

admixture). Thus, money and effort put into genetic work on Ponui or Hauturu

would be better spent managing the remnant wild NIB populations that are not

already known to have experienced bottlenecks or admixture.

If birds need to be taken off Hauturu or Ponui, then they should not be mixed with

remnant mainland populations or used to start new populations. The best

‘conservation’ use of these birds would be to move them to a secure captive facility

and use them for advocacy, or to leave the birds

in situ and use these populations

for scientific research (e.g., the consequences and dynamics of hybridization

between NIB taxa).

If there are specific remnant NIB populations that show low genetic variation (e.g.,

due to bottleneck effects) or evidence of inbreeding depression, then we

recommend that birds from populations that do not show evidence of admixture,

inbreeding or bottleneck effects be used for translocation into those populations for

genetic rescue. Additional genetic work for mainland NIB kiwi is required to

implement any genetic rescue required for these populations. This would include a

detailed analysis of the genetic divergence among and genetic diversity, inbreeding

and bottlenecks within remnant NIB populations. Such an analysis would allow K4K

to design translocation and genetic management for NIB that is focused on non-

admixed remnant populations.

Work currently being conducted by Dr Jason Weir will begin to address these

questions. Unfortunately, the 62 NIB samples Dr Weir has access to may not be

representative of the total genetic diversity across the current population of 25,000

NIB. More samples from a representative number of birds across the range of each

population will be required to adequately assess the population genetics of NIB.

Establishing how much inbreeding is present within and how much divergence exists

between NIB populations is key to their effective genetic management.

Our ref: Request for Advice – Expert Genetic

Advice Regarding the Use of Ponui and Little

Barrier Islands as Kiwi Translocation Founders

DOC- 2754937

18 April 2016

TO:

Kristina Ramstad, University of South Carolina Aiken

Jason Weir, University of Toronto

Helen Taylor and Neil Gemmell, University of Otago

Kevin Parker, Massey University

Fred Allendorf, University of Montana

Daniel White, Landcare Research

cc:

Kiwi Recovery Group

Rob Fenwick, Chairman Kiwis for kiwi

Bruce Parkes, DDG Science and Policy

Carol West, Director Terrestrial Ecosystems

FROM:

Jen Germano, Kiwi Recovery Group Leader

SUBJECT:

Request for Expert Genetic Advice Regarding the Use of Ponui and Little

Barrier Islands as a Kiwi Translocation Founders

Context:

The Kiwis for kiwi Trust is a non-profit organisation set up to fund and support community groups

and iwi, hapu and whānau working to increase kiwi numbers. The Trust is currently writing their 5

year investment strategy. They are aiming to be both proactive and strategic, as well as exploring

ways to increase cost and time efficiencies in recovering the numbers of North Island brown kiwi.

This is part of a wider partnership between the Department of Conservation, community,

iwi/hapu/whānau, captive institutions and others to turn the national decline of kiwi into a 2%

increase. We are seeking an opinion from you, as an international panel of conservation genetics

experts, on one aspect of the plan as outlined below. Kiwis for kiwi, the Kiwi Recovery Group, and

the Department of Conservation would greatly appreciate advice on this proposal.

Translocation Permitting Process

Any kiwi translocations currently carried out in New Zealand require a Wildlife Act Permit.

Consideration for any decision maker in this process will be the viability of newly established

populations. In order to avoid questions that may arise at the time of decision-making, it is

proposed to explore this with relevant experts now to:

1. Enable Kiwis for kiwi to ensure they have a viable 5-year investment strategy

2. Avoid unnecessary planning costs for translocation applications that are unlikely to be

approved

3. To provide direction on how LBI and Ponui birds can contribute to conservation efforts

Current Kiwi Taxonomic and Conservation Status:

Brown kiwi (

Apteryx mantelli) is the most common of the five species of kiwi, with a total estimated

population of 25,000 birds in 2008. The species is split into four geographical populations/

Evolutionary Significant Units/Conservation Management Units/taxa (Northland, Coromandel,

Eastern, Western) which Allan Baker’s lab in Canada has identified from mtDNA and nuclear DNA

work. Jason Weir’s recent SNP study and Oliver Haddrath’s additional mtDNA work has confirmed

that these four “regional” populations are distinctive and are likely to have diverged from one

another 100-200,000 years ago, perhaps as a result of volcanic activity in the central North Island.

Three “regional” populations (Northland, Eastern and Western) numbered about 8000 birds each

and Coromandel had about 1000 birds in 2008. Jason Weir’s work has established that none of the

four “regional” populations is significantly inbred and they are not in need of genetic rescue.

Mainland populations of brown kiwi are under threat from introduced predators (especially dogs

and stoats) and are declining at the rate of 2-3% per annum in unmanaged areas, but they are

increasing by up to 10% per annum in an increasing number of managed sites, through predator

trapping, aerial 1080 poison operations, Operation Nest Egg (ONE: a head-starting programme), or

by translocations from pest-free islands or fenced sanctuaries on the mainland (kohanga kiwi).

Little Barrier and Ponui Island Kiwi:

There are currently two island populations of brown kiwi on Little Barrier Island (LBI) and Ponui that

are both at or near carrying capacity. Kiwis for kiwi has a desire to use a large number of these island

birds to found new populations of kiwi on the mainland in sites where pests are being controlled,

and to establish a new population on a pest-free island.

The information we currently have on these populations is:

• The two island populations are founded from a mix of birds from at least two different

“regions” (Northland and Western).

• The founder numbers for these islands is believed to be very low.

• It is thought that LBI, which now has close to 1000 birds, was founded by a minimum of 3

Western birds (two transferred in 1902 and one white bird from the Taupo area released in

1913), perhaps 16 birds of unknown provenance liberated around 1919, and an unknown

number of native Northland-type birds that had persisted on the island for hundreds or

thousands of years. (The latter species was considered extinct in the late 1800s, but Oliver

Haddrath has identified the presence of Northland-type mtDNA in one of 15 samples.)

• The Ponui population, which now has c.500 birds, was founded in 1964 by 6 birds from LBI

and 8 birds from Northland, but the current genetic composition of the population is

unknown.

Modelling done with Allele Retain has suggested that for brown kiwi, founder sizes for translocation

populations should be a minimum of 40 unrelated birds, and so both island populations are

presumed to have been derived from well under this target number of founders, though liberations

of birds from two or more “regional” populations may have promoted outbreeding.

Advice requested:

1) Could these two island populations be used to found or supplement mainland or pest-free

island kiwi populations?

2) What are the genetic benefits and risks of establishing or supplementing kiwi populations

from these particular “mixed-provenance” populations with low founder numbers? Do the

benefits outweigh the risks?

3) Is the current historical information held sufficient from a genetic perspective to

assess Question 2 or do we need to assess the genetic composition of the two island

populations? If the current information is not sufficient, what information do we need, how

much would this cost, what sort of samples would be required and how long would the

analysis take?

4) Could the Ponui and Little Barrier kiwi populations be made into useful conservation assets

from a genetic perspective and if so, please provide some suggestions (e.g. genetic rescue of

these populations, supplementation of widespread mainland populations, other uses)?

It would be greatly appreciated if you could respond to me with a summary of the group’s collective

advice by May 13th.

Document Outline