6 July 2018

SUBMISSION

Please accept this as my submission in relation to how EPA conducts its risk assessments for new and

existing hazardous substances.

I am currently the Waikato Regional Councillor for Taupo-Rotorua and the Chair of WRC’s

Environmental and Services Performance Committee. Although some of my knowledge of the issues

addressed here have come through my council role, I am not submitting this on behalf of Council. It

is my personal submission.

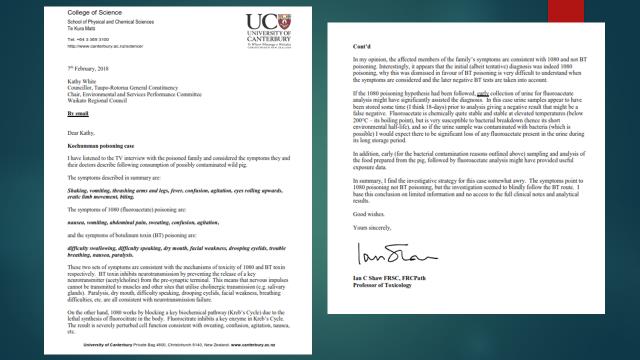

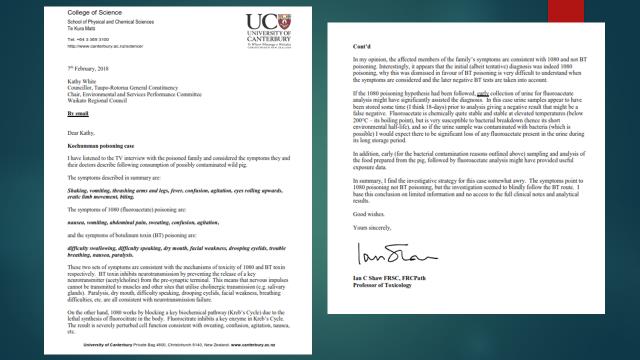

My comments are primarily in relation to vertebrate toxic agents, sodium fluoroacetate and

brodifacoum, as I believe that the risks involved in individual operations are much greater than you

have assessed and this highlights the deficiencies in the risk assessment methodology. This is partly

due to:

1.

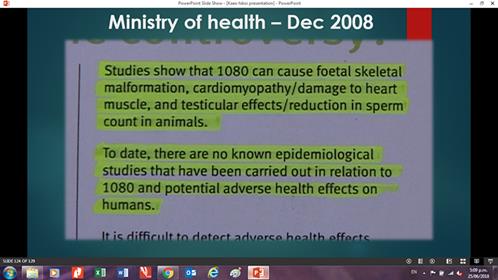

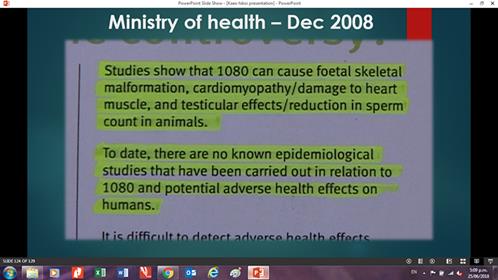

Vital studies not having been done (in a range of areas, but especially epidemiology) -

Official Information Act requests submitted in 2008 and 2018 confirmed that no

epidemiological studies have been conducted on 1080 (see appendix). These are studies

that should have been done to determine health risks to people, livestock, pets and wildlife,

before approval was ever granted to use 1080. No one has required this to happen over the

more than six decades of 1080 use. Epidemiological studies should be a requirement as part

of a risk assessment;

2.

Our technology not being as advanced as other countries - pesticides have been deemed

as harmful to mitochondria especially to the foetus at parts per trillion (UK), but in New

Zealand we only assess harm from 1080 at 2 parts per billion. This inadequacy in testing

technology prevents us from being able to do meaningful risk assessments in terms of

human and wildlife health;

3.

Not having testing facilities available for a number of essential tests - for example, we

cannot test for fluorocitrate in New Zealand, which is a metabolite of sodium flouroacetate.

Because the test isn’t available in New Zealand, it’s unlikely that the test is ever done, let

alone it being part of a testing protocol. Penny Fisher, previously of Landcare Research, told

me the fluorocitrate test is an important test for assessing the risk of 1080. I believe that

failure to provide facilities that can do such a test, when it’s known that this test would

probably produce positive results in many 1080 poisoning incidents, is in my opinion,

negligent;

4.

Agencies failing to follow Landcare Research protocols in terms of sampling and testing

water for 1080, leading to inaccurate analysis of total water testing results and distorted

risk assessments. The Landcare Research protocol states that tests should be done within 8

hours (when a test is most likely to be positive) and 24 hours after a 1080 drop (when the

toxin is likely to be diluted and undetectable). However the Medical Officer of Health does

not require the 8 hour test even though this is in the protocol. Agencies are not even asked

to state on the form what amount of time passed before the samples were taken. However

when I asked NIWA for information about this, I was told that all of the samples recently

taken for OSPRI were taken at 24 hours. As very few water tests are done at a time when

1080 is most likely to be detectable in water (within 8 hours) and all tests are lumped

together when reported no matter what time they are taken, statistics are skewed towards

negative results and a general conclusion that “1080 in water is safe.” This gives people a

false sense of security about 1080 in water, and has in fact led to more 1080 being

discharged to water. Imagine if people were not tested for alcohol in their breath until 24

hours after they had consumed it. It would be inaccurate to conclude that it is safe to

consume alcohol and drive, based on these test results. It would only tell us that alcohol is

no longer detectable. The reason for me using this analogy is in the following point.

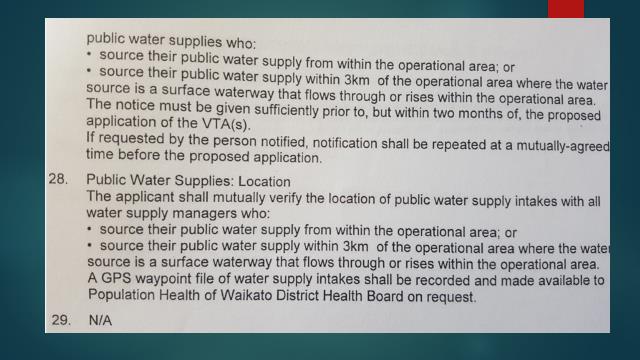

5.

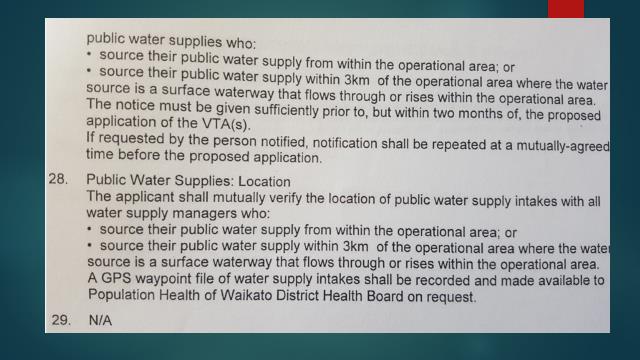

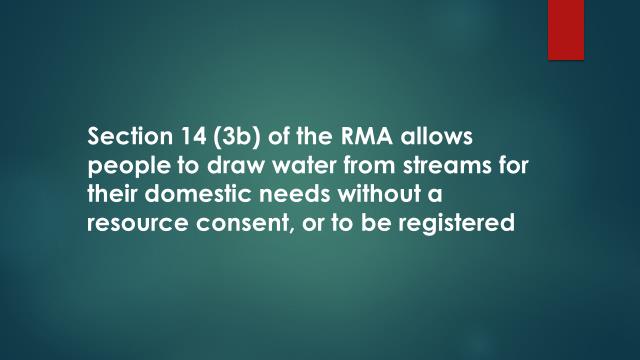

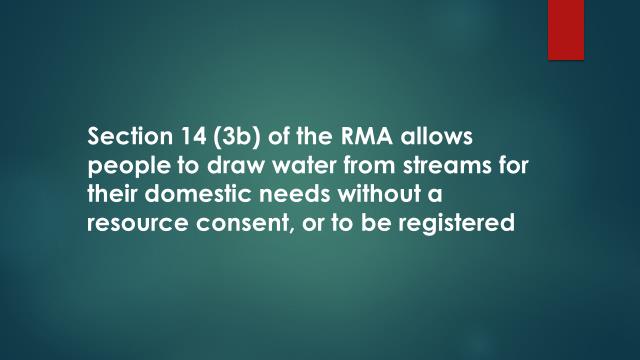

A lot of people have unregistered water takes, which is allowable under the RMA. These

people are at risk of 1080 poisoning because they continue to draw water via pipes from

streams, on the day of a poison drop because they have not been notified of the day and

time of the drop, and they have not been offered water mitigation. See appendix. The

Medical Officer of Health does not require DoC, OSPRI or other agencies to walk the streams

to identify unregistered people who are drawing water from streams (see DoC

correspondence). Many of these unregistered people are supplying water to large numbers

of people for domestic use and watering livestock. On the Coromandel Peninsula, we

identified one such person who was supplying water to 70 households plus stock. He had

not been advised to stop drawing water while the 1080 drop happened. This failure to

identify unregistered water takes, the failure to notify them of the need to stop drawing

water, and the failure to offer them an alternative water supply, is a huge risk to human-

and livestock-health. The EPA does not take this into consideration in a risk assessment.

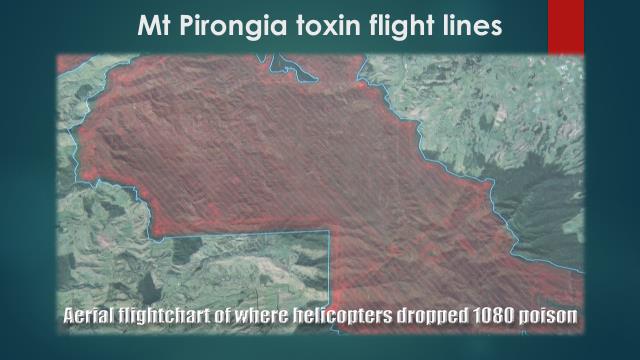

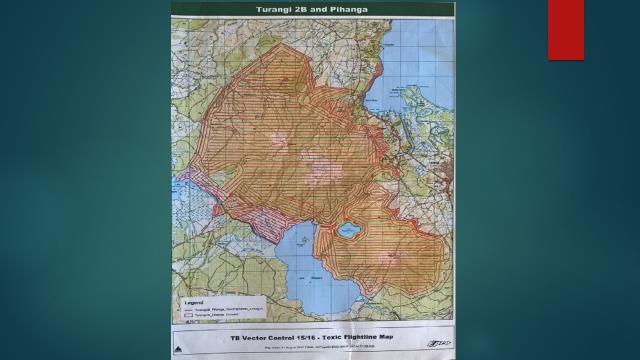

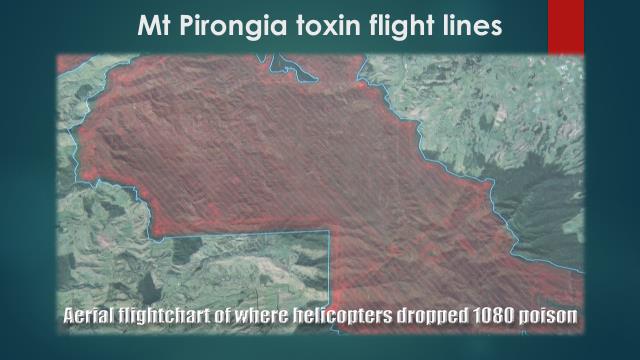

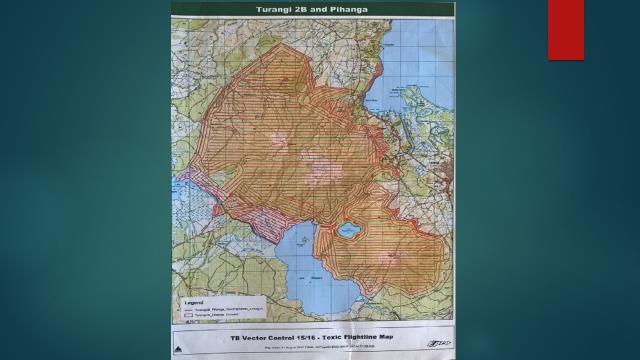

These large numbers of unregistered water users are at risk of poisoning in the hours

immediately after a poison drop because baits are dropped across almost all waterways, as

confirmed by official GPS toxin flight-charts of poison operations (see appendix flightcharts);

6.

People are unaware that 1080 is discharged into most waterways. Most people are

unaware that pest contractors are permitted to discharge 1080 baits across land and water.

There is nothing on the warning signs to indicate this, and there is no reason for people to

think that this would be allowed, given our attitudes to effluent and hazardous substances

in water. Warning signs and all correspondence should make it clear to people that poison

baits and carcasses may be present in water; entitlements to water mitigation should also

be made clear. This needs attention within your risk assessment methodology.

7.

Agencies not being fully transparent about by-kill numbers – there are numerous cases in

the Poisoning Incident Register (see working document at

https://docs.google.com/document/d/18c9NXa4NsZp5bzEm4WM8a

P_Us41DjXXMuxkHHcqap3U/edit?usp=sharing, and in correspondence

with agencies involved in poisoning, that indicate lack of transparency about pets, livestock

and wildlife that are killed unintentionally in poison operations

https://youtu.be/K7vtWj 5Utg The disparity between official records and veterinary

surveys, showing the number of dog deaths from 1080, for instance highlight that risk

assessments and decision-making has been flawed (see the article about the National

Poison Centre and Otago University survey regarding dog deaths by 1080).

http://www.scoop.co.nz/stories/SC1111/S00030/at-least-65-dogs-in-a-year-poisoned-by-

1080-in-new-zealand.htm

8.

Pest contractors not following label requirements – the manufacturer’s label and the

Safety Data Sheet in all its iterations over time, have made it clear that pest contractors

should avoid contaminating water with poison baits, and that where practicable, poisoned

carcasses should be removed or buried. This has recently been endorsed by Charles Eason

as best practice, but neither of these things are being done. Failure to remove poisoned

carcasses increases the secondary and tertiary risks of contaminating the food chain.

9.

Food chain contamination risks – pigs in particular are at risk from scavenging poisoned

carcasses (1080 and anticoagulants such as brodifacoum), but many other animals are also

at risk, such as eels and trout. There is a current warning out not to consume trout for a

week after a 1080 poison drop. Scientists have also warned recently that pigs can consume

large amounts of 1080 before succumbing to the toxin. Most people are not aware of such

risks. See appendix.

10. Maori concerns re 1080 contamination of mahinga kai, rongoa, and wahi tapu have been

widely ignored, as has the mauri of water. No one is able to guarantee that food sources

such as puha and watercress, pigs, koura and tuna have not been contaminated, or that

spiritual sensitivities have been protected.

11. A NES was not possible for 1080 because of the potentially significant adverse effects of

individual poison operations. This was a statement in the business case analysis of options

for streamlining the regulatory regime for 1080. Despite this, the government in 2017

pushed on to EXEMPT 1080, brodifacoum and rotenone from the protection of the RMA,

through their passing of the Exemptions Regulations. This legislation change has

dramatically increased the risk profile of 1080 because there are no longer resource

consents with conditions applied for individual operations. Consultation has reduced and

tensions have risen. This is something that needs seriously addressing in a risk assessment

methodology.

Benefits – the assessment of benefits versus costs has ignored the following:

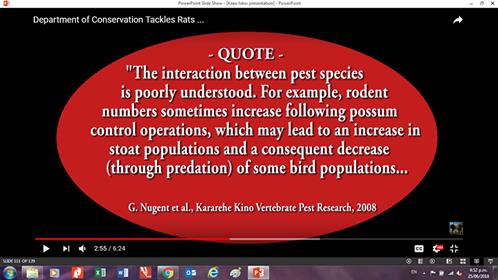

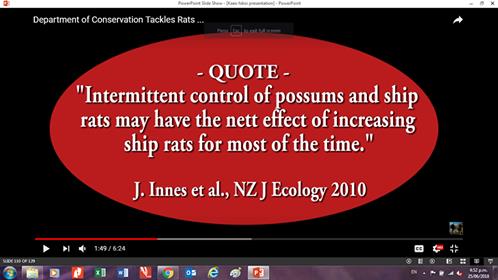

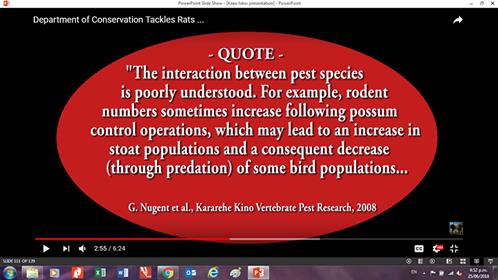

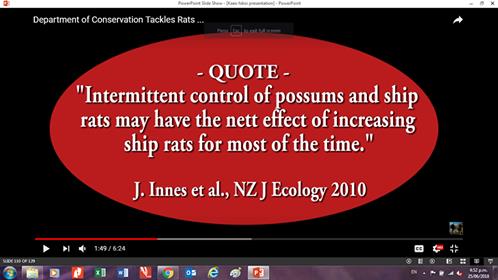

1. There is no evidence of long-term population benefit for native wildlife populations

from use of 1080 – Didham and Ruffell in 2016 investigated 195 pest-controlled

locations in the upper North Island, and declared that only two bird species had

benefited at a population level from pest control. “Pest control was found to affect

surprisingly few species with only kereru and tui being more abundant

https://newzealandecology.org/nzje/3296.pdf Negative unintended consequences are

common from pest control (Ruscoe study). Rat numbers often explode within six

months of a 1080 drop.

2. Underestimating the risks of 1080 or other toxins to birds that are small, vulnerable,

in low numbers, or are slow to breed. Kea for instance are at high risk in areas where

1080 is used. Their populations have dwindled significantly from being high numbers at

a time when there were also plenty of possums, rats and stoats, to being extremely low

numbers at a time when money spent on toxins in pest control has never been higher.

The risk assessment for kea has failed, because toxins continue to be used in these

areas despite OIA records proving that high numbers of kea have been found dead with

1080 residues.

3. Areas where 1080 has not been used are not being adequately studied to enable

quality cost-benefit analysis and comparisons. For instance, the Okahu Valley (where

no 1080 is used) has healthy populations of kiwi. Kiwi chicks and eggs are often

translocated from this unpoisoned area to poisoned areas. In contrast, in places where

vast quantities of toxins have been used, such as the Pukaha sanctuary (Mt Bruce) and

the Tongariro National Park, there have been very poor results in terms of kiwi surviving

to adulthood. The costs of using 1080 are high, not just in economic terms. The benefits

are exaggerated. See the following videos about high numbers of kiwi deaths in Pukaha

https://youtu.be/yGTVaTATbOg and Tongariro https://youtu.be/1gR674m7a00

4. The risk of 1080 to our Clean, Green 100% Pure brand - we have no idea how much

our country’s widespread use of 1080 has impacted on people’s ability to make a living

and export products. We know people who have been prevented from using possum

meat and fibre, and wild venison in products destined for overseas markets, but we

don’t know how many opportunities we have missed because people know that we use

one of the world’s deadliest poisons aerially near and on farms. There have also been

scares where products such as butter have been quarantined. Any risk assessment

should also consider the opportunity costs and benefits to our country’s brand.

Regards

Kathy White

APPENDIX

APPENDIX

Permission issued by the Medical Officer of Health for discharge of 1080