link to page 3 link to page 3 link to page 6 link to page 6 link to page 6 link to page 7 link to page 8 link to page 9 link to page 9 link to page 11 link to page 13 link to page 13 link to page 15 link to page 15 link to page 15 link to page 16 link to page 16 link to page 17 link to page 18 link to page 18 link to page 19 link to page 19 link to page 20 link to page 20 link to page 21 link to page 21 link to page 21 link to page 21 link to page 22 link to page 23 link to page 23 link to page 23 link to page 23 link to page 24 link to page 24 link to page 24 link to page 24 link to page 25 link to page 25 link to page 25 link to page 25 link to page 25 link to page 26 link to page 26 link to page 26 link to page 26 link to page 26 link to page 27 link to page 28

Child protection investigation policy

and procedures

Detailed table of contents

This chapter contains these topics:

Executive summary - policy and principles

• The Police commitment to victims

• Principles guiding Police practice

• Summary of child abuse policies guiding Police practice

Overview

•

Purpose

•

Who do the investigation policy and procedures apply to?

•

Background

•

Related information

Definitions and assessing seriousness of abuse

•

Definitions

•

Determining seriousness of physical abuse

Key processes in child abuse investigations

•

Case management links

Initial actions and safety assessment

•

Introduction

•

Procedure when a report of concern is received

•

Options for removing a child

-

Powers of removal

•

Managing children found in clandestine laboratories

Consultation and initial joint investigation planning with Oranga Tamariki

•

Consultation procedures

•

Initial joint investigation plans

-

Updating initial joint investigation plans

•

CPP meeting to discuss cases

•

Cases falling outside of the Child Protection Protocol Joint Operating Procedures

Making referrals to ORANGA TAMARIKI

•

Types of cases requiring referral to Oranga Tamariki

-

Flowchart

•

Referral process varies depending on case type

•

Referral of historic cases to Oranga Tamariki

Interviewing victims, witnesses and suspects

•

Interviewing children in child abuse investigations

•

Interviewing adult witnesses

•

Interviewing suspects

Medical forensic examinations

•

Primary objective of the examination

•

Timing of examinations

•

Arranging the medical

-

Specialist medical practitioners to conduct examinations

-

Support during the examination

•

Examination venues

•

Examination procedures

•

Photographing injuries

Evidence gathering and assessment

•

Police responsibility for criminal investigations

•

Crime scene examination

•

Consider all investigative opportunities

•

Exhibits

•

Dealing with suspects

•

Ongoing evidence assessment

As at 15/07/2020

Page 1 of 39

link to page 28 link to page 28 link to page 29 link to page 29 link to page 29 link to page 29 link to page 29 link to page 30 link to page 30 link to page 31 link to page 32 link to page 32 link to page 32 link to page 32 link to page 32 link to page 33 link to page 33 link to page 34 link to page 34 link to page 34 link to page 34 link to page 34 link to page 34 link to page 35 link to page 35 link to page 35 link to page 35 link to page 36 link to page 36 link to page 36 link to page 36 link to page 37 link to page 37 link to page 37 link to page 37 link to page 37 link to page 37 link to page 37 link to page 38 link to page 39

Child protection investigation policy and

procedures,

Continued...

-

Care and protection concerns arising during investigation

•

Community disclosure of offender's information

Hospital admissions for non-accidental injuries or neglect

•

Introduction

•

Medical case conferences

-

DHB immediate management plan

•

Multi agency safety plan

-

Reviewing multi agency safety plans

•

Medical information available to investigators

•

Further information

Charging offenders and considering bail

•

Determining appropriate charges

•

DNA sampling when intending to charge

-

Relevant offences

•

Determine if the offence falls within s29 Victims' Rights Act

•

Bail for child abuse offending

-

Victims views on bail

Prosecution and other case resolutions

•

Options for resolving child abuse investigations

•

Deciding whether to prosecute

-

Related information if case involves family violence

•

Matters to consider during prosecutions

•

Disclosure of video records and transcripts

•

Preparing witness before court appearance

•

Privacy of victims in court

•

Support of witnesses in court

•

Preparing victim impact statements

Responsibilities for victims

•

Victims may include parents and guardians

•

Rights of victims

•

Support after sexual violence

Final actions and case closure

•

Information to be provided to victim

•

Oranga Tamariki notification

•

Sex offender/suspect notification

•

Return of exhibits

•

Return and retention of video records

-

Destruction of master copies, working copies and other of video records

•

File completion

Health and safety duties

As at 15/07/2020

Page 2 of 39

link to page 9

Child protection investigation policy and

procedures,

Continued...

Executive summary – policy and principles

The Police commitment to victims

Police will assess all reports of child safety concerns received and:

• take immediate steps to secure the child’s safety and well being. This is the first and

paramount consideration including identifying and seeking support from family

members and others who can help

• intervene to ensure the child’s rights and interests are safeguarded

• investigate all reports of child abuse in a

child centred timeframe, using a multi-

agency approach

• take effective action against offenders so they can be held accountable

• strive to better understand the needs of victims

• keep victims and/or their families fully informed during investigations with timely and

accurate information as required by

s12 of the Victims Rights Act 2002.

Principles guiding Police practice

These principles must be applied when responding to reports of child safety concerns.

Description

Principles

Rights of the

• Every child has the right to a safe and nurturing environment.

child

• Every child has the right to live in families free from violence.

• Every child has the right to protection from all forms of physical

or mental violence, injury or abuse, neglect, or negligent

treatment, maltreatment or exploitation, including sexual abuse,

while in the care of parent(s), legal guardian(s) or any other

person who has the care of the child (see Article 19(1) of the

United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child 1989)

• Every child has the right to protection from all forms of sexual

exploitation and sexual abuse, in particular:

- the inducement or coercion of a child to engage in any

unlawful sexual activity

- the exploitative use of children in prostitution or other

unlawful sexual practices

- the exploitative use of children in pornographic performances

and materials

(see Article 34 of the United Nations Convention on the Rights

of the Child 1989).

Accountability

• Child abuse, in many of its forms, is a criminal act which will be

thoroughly investigated and the offender(s) held to account,

wherever possible.

Working

• Police will adopt a proactive multi-agency approach to prevent

collaboratively

and reduce child abuse through well developed strategic

partnerships, collaboration and cooperation between policing

jurisdictions, government and non government agencies.

• Police will maintain integrated and coordinated information

gathering and intelligence sharing methods locally, nationally

and internationally.

Service delivery

• Police will make use of new technology and other innovations

allowing them to work faster and smarter in response to child

abuse.

Summary of child abuse policies guiding Police practice

This table summarises specific Police policies relating to reports of child safety concerns

and the investigation of child abuse.

As at 15/07/2020

Page 3 of 39

link to page 10

Child protection investigation policy and

procedures,

Continued...

Practice

Policies and/or responsibilities

relating to…

Victims

• All obligations under t

he Victims Rights Act 2002 must be met

and all victim contact must be recorded.

• Victims must be given information about the progress of their

investigation within 21 days.

• Victims must be kept updated and informed of the outcome of

the investigation, including no further avenues of enquiry or the

reason for charges not being laid.

• As soon as the offender is arrested and charged, Police must:

- determine whether it is a

s29 offence, and if so

- inform the victim of their right to register on the Victim

Notification System (if they wish to do so).

• Victims must be informed of the outcome of the case and the

case closure. Any property belonging to the victim must be

returned promptly.

Investigations

• All reports of child safety concerns must be thoroughly

investigated in accordance with this chapter.

• All reports of child abuse made by children must be thoroughly

investigated in accordance with this chapter, even if the child

recants or parents or care givers are reluctant to continue.

• Police must take immediate steps to ensure the safety of any

child who is the subject of a report of concern or is present in

unsafe environments, including family violence.

• All reports of historic child abuse should be investigated in

accordance with the

Adult sexual assault investigation policy and

procedures and may include early consultation with child

protection investigators and Oranga Tamariki.

• All child abuse investigations must be managed in accordance

with the case management business process.

• All referrals made under the Child Protection Protocol Joint

Operating Procedures

(CPP) must comply with the protocol.

• Oranga Tamariki inquiries do not negate the need for Police to

conduct its own investigations into alleged child abuse.

• Interviews of a child must be conducted in accordance with the

Specialist Child Witness Interview Guide, by a trained specialist

child witness interviewer and comply with the

Evidence

Regulations 2007.

Investigators

• Investigators on child protection teams should be exclusively

focused on child abuse investigations. Where circumstances

require it, investigators on

Child Protection Teams must only

work on non-child protection matters for the shortest duration

possible.

• Investigators must consider the possibility of the suspect

continuing to offend against any child during the course of the

investigation and take appropriate action to mitigate the risk.

• Investigators of child abuse must be trained investigators (see

‘Child protection tiered training and accreditation’ in the

‘Child

protection – Specialist accreditation, case management and

assurance’ chapter).

• Where investigators are uniform attachments they may only be

the O/C (file holder/lead investigator) for physical assault cases

where the maximum penalty is no more than 5 years

imprisonment. The investigation of such cases must be under

the direction/supervision of a level 3 qualified investigator or a

As at 15/07/2020

Page 4 of 39

Child protection investigation policy and

procedures,

Continued...

level 4 qualified supervisor. They must not hold any sexual

offending files.

• All child protection investigators must comply with the

Wellcheck

support policy. Child protection investigators may, from time to

time, for personal or organisational reasons, need to be moved

out of investigating child abuse and into more general areas of

policing.

File

• All reports of child safety concerns must be recorded in NIA with

management

a 6C incident code in addition to the appropriate offence code

when an offence has clearly been identified.

• All information must be recorded in accordance with the

National

Recording Standards (NRS).

• All child abuse cases must be:

- managed using the NIA case management functionality

- categorised in NIA case management as “2 Critical.”

• All reports of concern must only be filed by a level 4 CP trained

substantive Detective Senior Sergeant (or substantive Detective

Sergeant in relieving capacity) who has also received operational

sign off from the District Crime Manager. In most instances filing

will be completed by the District Child Protection Co-ordinator

following review by the CPT supervisor.

Oversight and

As pe

r Quality Assurance and Improvement Framework (QAIF):

Monitoring

• supervisors of child protection investigators must review one file

from each child protection investigator every four months with

the results reported back to the individuals and District CP

Coordinator.

• District CP Coordinators and/or District Crime Managers must

review cases from a list provided every four months by PNHQ

with the results reported back to supervisors and the Manager

Sexual Violence and Child Protection Team

• the Manager Sexual Violence and Child Protection Team must:

- review a sample of files from every district on a yearly basis

with results reported to districts and the Police Executive

- ensure that districts comply with the audit and assurance

framework and report to districts and the Police Executive on

a quarterly basis.

Training

The Training Service Centre and the National Sexual Violence and

Child Protection Team must provide the means for:

• all employees to understand child abuse and neglect

• investigators to gain the necessary skills and knowledge to

conduct child protection investigations

• specialist child witness interviewers to gain the necessary skills

and knowledge to conduct child interviews.

Local Level

• Local Level Service Agreements must only address local service

Service

delivery matters particular to the districts or area that are not

Agreements

already covered by the CPP.

As at 15/07/2020

Page 5 of 39

link to page 9 link to page 13

Child protection investigation policy and

procedures,

Continued...

Overview

Purpose

This Police Manual chapter details:

• policy and principles guiding Police response to

child safety concerns:

-

including child abuse, neglect, online offending against children, and abuse arising

from children being present in unsafe environments

-

excluding child safety concerns arising from missing persons, truants, or child and

youth offenders. See the

Missing persons and

Youth justice chapters for procedures

in these areas

•

procedures for responding to and investigating reports to Police about child safety

concerns.

These policies and procedures are designed to ensure timely, coordinated and effective

action in response to information about child safety concerns so that children are kept

safe, offenders are held accountable wherever possible, and child victimisation is

reduced.

Related child protection policies and procedures

These related child protection chapters detail further policies and procedures around

specific aspects of Police child protection work:

•

Child Protection Policy (overarching policy) - outlines the various policies that together

comprise the Police ‘Child Protection Policy’ and provides an overview of our

obligations under the

Vulnerable Children Act 2014

•

Child protection – Mass allegation investigation

•

Child protection – Investigating online offences against children

•

Child protection – Specialist accreditation, case management and assurance

•

Child Protection Protocol: Joint operating Procedures (CPP) – between Police and

Ministry of Vulnerable Children (Oranga Tamariki)

• Joint Standard Operating Procedures for Children and Young Persons in Clandestine

Laboratories

Who do the investigation policy and procedures apply to?

These ‘Child protection investigation policy and procedures’ apply to all cases where the

victim is under the age of 18 at the time of making the complaint.

Follow the

Adult sexual assault investigation policy and procedures in cases of sexual

abuse where the victim is 18 years of age or older at the time of making the complaint.

Exceptions

Many cases have individual circumstances warranting different approaches to achieve

the most favourable outcomes for victims. There may be situations where adult victims

will be dealt with according to these procedures, depending on the nature and

circumstances of the victim and the offending — e.g. an adult victim with intellectual

disabilities being forensically interviewed as a child.

Investigations into reports of

historic child abuse, i.e. reports by an adult victim of

child abuse that occurred against them when they were a child:

• should be conducted in accordance with

Adult sexual assault investigation policy and

procedures

• should include early consultation with specialist child protection investigators and

Oranga Tamariki to consider other children who may be at risk, any relevant history

and potential for other related offending by the offender

As at 15/07/2020

Page 6 of 39

link to page 22 link to page 22 link to page 7 link to page 7 link to page 7

Child protection investigation policy and

procedures,

Continued...

• may still require referral to Oranga Tamariki (see

Referral of historic cases to Oranga

Tamariki for further information).

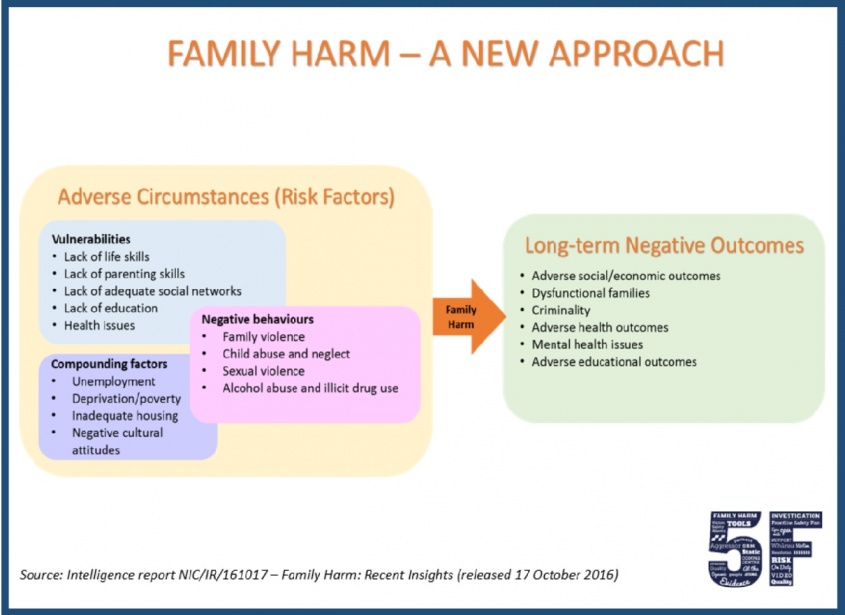

Background

Children are one of the most vulnerable members of the community. It is well recognised

that child abuse has a devastating effect on the development and growth of a child.

Children exposed to child abuse are more likely than other children to grow up to be

victims of violence, to perpetrate violence or be involved in other criminal offending.

Child abuse is a crime that often goes unreported with some child victims simply unable

to make a complaint against the offender. Child abuse is commonly found within a family

setting. Even if a child is capable of making a complaint, the pressures of the family

dynamic will often prevent them from doing so in the first instance, or persisting with the

complaint if one is made.

Child safety is a critical issue and the investigation of child abuse is given a high priority

by Police. Police has adopted a broad approach to child safety to ensure no child falls

through the cracks and is committed to a prompt, effective and nationally consistent

response to child safety, in conjunction with other agencies and community partners.

The use of formal processes ensures all the elements of good child protection practice

are applied.

Initial information about child safety concerns may come from a range of sources and

only rarely will the initial notification come directly from the child. Most often the report

comes through Oranga Tamariki.

When a report of concern is received, the safety and well being of the child is the first

and paramount consideration. Police cannot achieve this on its’ own or in isolation from

other partner agencies. An inter-agency approach is necessary to ensure the child’s

protection, enhance the accountability of the offender, and to enhance the child’s partial

or full reintegration into the family where appropriate.

There are subtle differences between investigating reports of child safety concerns and

other criminal enquiries. Most notable is the power imbalance between the child and the

offender, and the subsequent impact and consequences of abuse on the victim.

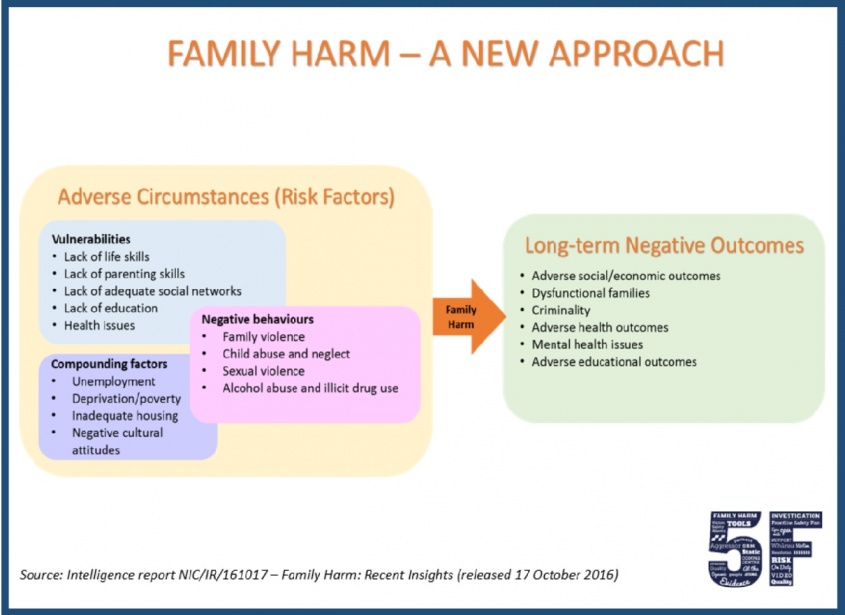

Family violence cases

The effect of exposure to family violence on children has a significant and negative

effect, whether they witness it, or are direct victims of it.

1

For CPP cases where the abuse has occurred within a family or whānau context

2 it is

important to refer cases to the appropriate family violence multi-agency forum

3 for

consideration. For Police, the CP Team must advise their District/Area Family Harm

Coordinator or equivalent of any CPP cases considered to be family violence. Do this by

entering a tasking to the District Family Harm Coordinator bringing the CPP file to their

attention.

When working with families who have experienced family violence, staff Oranga Tamariki

should consider and assess the cumulative effect of psychological harm, including the

current impact of past and/or present violence. (For more information on circumstances

in which a child or young person is suffering, or is likely to suffer, serious harm see

1 Joint Findings of Coroner C D na Nagara as to Comments and Recommendations – Flaxmere Suicides, 6 May 2016.

2 The parties involved in the situation are family members. Family members include people such as parents, children,

extended family and whānau. They do not need to live at the same address.

3 Currently this is the Family Violence Interagency Response System (FVIARS).

As at 15/07/2020

Page 7 of 39

link to page 8

Child protection investigation policy and

procedures,

Continued...

section 14AA of the Oranga Tamiriki Act 1989). This includes assessment of prior reports

of concern which did not meet the threshold for further action to be taken. This is

important as the physical and psychological consequences are highly individualised and

can vary from intense and immediate, to cumulative and long lasting. Research

demonstrates that children living with violence in their families are at increased risk of

experiencing physical or sexual abuse.

4

Calls to Police to intervene in family violence represent a vital opportunity for police to

consider and make appropriate referrals to ensure effective child protection.

Impact on Maori

Maori are significantly over represented as victims and perpetrators of child abuse and

family violence. Given this over-representation, it is extremely important that Police

focus resources and effort effectively for prevention and the investigation of cases. Maori

service providers and whänau should be engaged wherever possible to provide additional

support through Whangaia Nga Pa Harekeke. In addition, all districts have Iwi Liaison

Officers who should be used when dealing with child safety concerns. Each District, and

some Areas, also have Maori Advisory Boards who can assist with identifying service

providers and engaging whänau for additional support. This will be easier if the iwi/hapu

affiliations of children and their families are ascertained.

Non-indigenous cultural considerations

Nowadays, 1 in 5 New Zealand residents is born overseas. When immigrants settle in

New Zealand they bring with them diverse cultural and religious backgrounds that can

affect the way violence manifests and create barriers to seeking help. Those

backgrounds can include direct and indirect exposure to the ideology and practice of

Female Genital Mutilation (FGM) and under-age marriage.

Related information

This chapter should be read in conjunction with the

Child Protection Protocol: Joint

Operating Procedures (agreed between Police and Oranga Tamariki) and the

Family

harm policy and procedures.

Other related information includes:

•

Police safety orders

•

Protection and property-related orders

•

Adult sexual assault investigation policy and procedures

•

Police response to bullying of children and young people

•

Forced and under age marriage

• Multi-agency Statement on a Collaborative Response to Potential and Actual Forced

Marriage

• United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child (UNCROC)

•

Objectionable publications (includes guidance on ‘Indecent communication with a

young person’

•

Wellcheck Support Policy

• Prevention and Reduction of Family Violence - An Australasian Policing Strategy

4 Farmer, E. & Pollack, S. (1998).

Substitute Care for Sexually Abused and Abusing Children. Chichester: Wiley; Edleson, J.

(1999). Children witnessing of adult domestic violence.

Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 14(4)839-70; Cawson, P. (2002)

Child Maltreatment in the Family: The Experience of a National Sample of Young People. In C. Humphreys, & N. Stanley (eds)

(2006)

Domestic Violence and Child Protection: Directions for Good Practice. Jessica Kingsley: London.

As at 15/07/2020

Page 8 of 39

link to page 11 link to page 11 link to page 10 link to page 11 link to page 11 link to page 9

Child protection investigation policy and

procedures,

Continued...

Definitions and assessing seriousness of abuse

Definitions

This table outlines the meanings of terms used in this chapter.

Term

Meaning

6C Incident code

Any report of concern received by Police where a child is the

victim.

Acute child abuse Child abuse occurring less than 7 days before it was reported.

Adult

A person aged 18 years or older.

Case

An investigation plan describes the investigation process. It

investigation plan translates the objectives from the Terms of Reference into a

plan that sets out roles, responsibilities, timeframes, principal

activities, critical decision points and objectives for any

investigation.

Child

Unless specified, ‘child’ means any child or young person under

the age of 18 years at the time of their referral but does not

include any person who is or has been married (or in a civil

union).

Child abuse

Child abuse is defined in the Oranga Tamariki Act 1989 as the

harming (whether physically, emotionally, or sexually), ill-

treatment, abuse, neglect, or deprivation of any child or young

person.

If the victim is a child and one or more of the following exist,

the report of concern should be treated as child abuse:

•

physical, sexual, emotional or psychological abuse

•

neglect

• presence in unsafe environments (e.g. locations for drug

manufacturing or supply)

• cyber crime exploiting children

• child trafficking.

Child centred

Child centred timeframes are timeframes that are relevant to

timeframes

the child’s age and cognitive development.

Child protection

Trained investigators, often in remote or rural locations,

portfolio holders

responsible for investigating reports of concern about child

safety. These investigators are not exclusively focussed on child

protection and may be called upon to investigate other serious

crime in the location.

Child safety

Child safety concerns include offences or suspected offences

concerns

relating to the physical, sexual, emotional abuse or neglect of a

child. These categories overlap and a child in need of protection

frequently suffers more than one type of abuse.

CPP

The

CPP exists to ensure timely, coordinated and effective action

(Child Protection

by Oranga Tamariki and Police so that:

Protocol Joint

• children are kept safe

Operating

• offenders are held to account wherever possible

Procedures)

• child victimisation is reduced.

The CPP sets out the process for working collaboratively at the

local level, and as a formally agreed national level document, it

will be followed by all Oranga Tamariki and Police staff.

CPP case

An agreed case between Police and Oranga Tamariki of child

abuse being investigated in accordance with the

CPP.

As at 15/07/2020

Page 9 of 39

link to page 9

Child protection investigation policy and

procedures,

Continued...

CPP case list

A complete list of all CPP cases that are open to either Oranga

Tamariki, Police or both. This list is generated by Oranga

Tamariki using the Te Pakoro Report 100 CPP Case List. This list

is reviewed at least monthly during the CPP meetings.

CPP contact

The Oranga Tamariki staff member with responsibility for

person (Oranga

overseeing CPP cases in a site.

Tamariki)

CPT

A Child Protection Team (CPT) is exclusively focussed on

(Child Protection

responding to reports of child safety concerns. A CPT is made

Team)

up of trained investigators reporting to a supervisor.

Oranga Tamariki

Was Child, Youth and Family

Oranga Tamariki

These are the categories used by Oranga Tamariki.

timeframes

Category

The child or young person is…

Critical

No safety or care identified; mokopuna is at risk

24hrs

of serious harm, and requires immediate

involvement to establish safety.

Very urgent At risk of serious harm but has some protective

48hrs

factors present for the next 48 hours. However,

as the present situation and/or need is likely to

change, high priority follow up is required.

Urgent

At risk of harm or neglect and the

7 days

circumstances are likely to negatively impact on

mokopuna. Options of safety and supports have

been explored but remain unmet. Vulnerability

and pattern exists which limits the protective

factors.

Emotional abuse

Emotional abuse is the persistent emotional ill treatment of a

child, which causes severe and persistent effects on the child’s

emotional development.

Harm

Ill treatment or the impairment of health or development,

including impairment suffered from seeing or hearing the ill

treatment of another.

Historic child

Reports by an adult victim of

child abuse that occurred against

abuse

them when they were a child and they are over 18 at time of

reporting the abuse.

(Adult Sexual Assault procedures apply)

Initial joint

An initial plan jointly created by Oranga Tamariki and Police to

investigation plan record agreed actions on the agreed template.

(IJIP)

Iwi, Pacific and

Police employee, usually (but not always) a constable, with

Ethnic Liaison

indigenous and/or ethnic language and cultural skills,

Officers

responsible for managing relationships between Police and

Maori, Pacific and Ethnic communities.

As at 15/07/2020

Page 10 of 39

link to page 9 link to page 11 link to page 11

Child protection investigation policy and

procedures,

Continued...

Neglect

Neglect within the

CPP context is when a person intentionally ill-

treats or neglects a child or causes or permits the child to be ill-

treated in a manner likely to cause the child actual bodily harm,

injury to health or any mental disorder or disability. The ill-

treatment or neglect must be serious, and avoidable.

For example:

• not providing adequate food, shelter or clothing

• not protecting a child from physical harm or danger

• not accessing appropriate medical treatment or care[1]

• allowing a child to be exposed to the illicit drug

manufacturing process

• allowing a child to be exposed to an environment where

volatile, toxic, or flammable chemicals have been used or

stored.

Physical abuse

The actions of an offender that result in or could potentially

result in physical harm or injury being inflicted on a child. This

can also be known as a non-accidental injury (NAI). The test for

seriousness is determined by considering the action, the injury

and the circumstances (see

Determining seriousness of physical

abuse below).

Psychological

A person psychologically abuses a child if they:

abuse

• cause or allow the child to see or hear the physical, sexual, or

psychological abuse of a person with whom the child has a

domestic relationship, or

• puts the child, or allows the child to be put, at real risk of

seeing or hearing that abuse occurring.

(s3 Domestic Violence Act 1995)

Note: The person who suffers the abuse is not regarded (for the

purposes of

s3(3)) as having:

• caused or allowed the child to see or hear the abuse, or

• put the child, or allowed the child to be put, at risk of seeing

or hearing the abuse.

Sexual abuse

Sexual abuse is an act involving circumstances of indecency

with, or sexual violation of, a child, or using a child in the

making of sexual imaging.

Specialist child

A recorded interview that can be used as part of an investigation

witness interview where a child has, or may have been, abused or witnessed a

(SCWI)

serious crime. It may later be used as evidence in the Court.

Victim

A person against whom an offence is committed by another

person. A victim may also include a parent or legal guardian of a

child or young person.

Determining seriousness of physical abuse

There are three areas to consider in determining whether physical abuse meets the

threshold for referral as a CPP case:

1. the action (of the abuse)

2. the injury inflicted (outcome or result)

3. the circumstances (factors in the case).

Any single action and/or injury listed below will

meet the threshold for referral as a CPP

case.

As at 15/07/2020

Page 11 of 39

Child protection investigation policy and

procedures,

Continued...

Any of these actions (methodology, how it was done)

• blow or kick to head

• shaking of an infant

• strangulation

• use of an object as a weapon (e.g. broom, belt, bat etc)

• attempted drowning.

OR

Any of these injuries (outcome or result)

• a bone fracture

• burn

• concussion or loss of consciousness

• any injury that requires medical attention

• any bruising or abrasion when the:

- child is very young, e.g. infant not yet mobile and/or,

- the position and patterning make it unlikely to be caused by play or another child

or accident.

Circumstances or factors of the case

Where the initial action or injury does not meet the threshold outlined above, the

following circumstances or factors may warrant referral as a CPP case.

Factor / background Consider …

The vulnerability of the

especially:

child

• children under 5 years

• age and vulnerability of pre-pubescent children

• disabilities in any age

More than one offender for example:

• both parents/caregivers

• multiple family members

History of abuse

• other incidents of concern, escalation of abuse

• multiple previous similar events

• previous non-accidental death of a sibling or child in

household

• abuse undertaken in public or in front of non-relatives.

A high degree of

• a complete loss of control by the offender, such as a

violence

frenzied attack

• enhanced maliciousness or cruelty in the abuse

• the degree in relation to age and vulnerability of the

victim

The offender's history

• severe and frequent family violence

and background

• serious or extended criminal history

Location of the incident for example:

• educational, care, or health facility

Nature and level of

• notifier witnessed abuse

concern from the

• notifier’s source

notifier

• professional opinion indicates serious concern.

As at 15/07/2020

Page 12 of 39

link to page 15 link to page 15 link to page 17 link to page 17 link to page 18 link to page 18 link to page 18 link to page 21 link to page 21 link to page 24 link to page 26 link to page 26

Child protection investigation policy and

procedures,

Continued...

Key processes in child abuse investigations

Case management links

This table aligns the case management process steps that apply to Police investigations

generally and provides links to relevant information and requirements in these

procedures, specific to child abuse investigations.

Not all steps will apply in every case and the order may vary depending on the individual

circumstances.

Process

Case management action

Related procedures in this or in

step

other Police Manual chapters

Step 1

Record incident, event or

occurrence

Details are recorded into the Police

computer system and a case

created.

All reports of child safety concerns

must be recorded in NIA with the 6C

incident code in

addition to the

appropriate offence code when an

offence has clearly been identified.

Step 2

Initial attendance

• Initial actions and safety

Police respond to the report,

assessment

enquiries commence, evidence is

- immediate actions (e.g.

gathered or other action taken as

removal) to ensure the child’s

necessary.

safety

- managing children found in

clandestine laboratories (joint

operating procedures with

Oranga Tamariki)

• Consultation and initial joint

investigation planning with

Oranga Tamariki

• Making referrals to Oranga

Tamariki

After initial assessment,

referring cases to Oranga

Tamariki to agree future actions

and priority.

Step 3

Gather and process forensics

•

Medical forensic examinations

Detailed scientific scene examination

• Evidence gathering and

is conducted. Forensic evidence is

assessment

gathered and analysed, and its

relevance recorded and assessed.

Step 4

Assess and link case

Consider the application of

Initial assessment and review of all

procedures in the Child protection -

available information. Other related

'Mass allegation investigation' and

or relevant cases are identified.

'Investigating online offences

Cases are closed (filed, or

against children' chapters.

inactivated) or forwarded to

appropriate work groups for further

investigation.

As at 15/07/2020

Page 13 of 39

link to page 18 link to page 18 link to page 18 link to page 21 link to page 21 link to page 23 link to page 23 link to page 24 link to page 26 link to page 26 link to page 23 link to page 32 link to page 32 link to page 34 link to page 34 link to page 37 link to page 35

Child protection investigation policy and

procedures,

Continued...

Step 5

Prioritise case

• Consultation and joint

Cases identified for further

investigation planning with

investigation are assigned a case

Oranga Tamariki

priority rating score based on crime

• Making referrals to Oranga

type and the presence of factors

Tamariki

affecting the need for urgent

After an initial assessment of the

investigation.

case, cases are referred to

Oranga Tamariki for consultation

All child abuse cases are recorded as

and to agree future actions and

“2. Critical” under NIA Case

priority.

Management.

Step 6

Investigate case

• Interviewing victims and

Initial investigation is conducted to

witnesses

bring the case to a point where a

•

Medical forensic examinations

suspect can be identified and all

• Evidence gathering and

preliminary enquiries necessary

assessment

before interviews are complete.

• Consider appropriate strategies

for

mass allegations and

online

offending investigations

•

Interviewing suspects

Step 7

Resolution decision/action

• Charging offenders and

Deciding on formal or informal

considering bail

sanctions, prosecution or other

• Prosecution and other case

action, confirming the

resolutions

appropriateness of charges and

offender handling and custody suite

actions.

Step 8

Prepare case

• Prosecution file and trial

Court files are prepared, permission

preparation

to charge obtained from supervisor

•

Criminal disclosure

and actions such as disclosure

completed.

Step 9

Court process

• Criminal procedure - Review

Where a not guilty plea is entered, a

stage (CMM process)

case management memorandum

and case review hearing occurs

before trial (judge alone - categories

2 & 3, or trial by jury - categories 3

& 4).

Step 10

Case disposal and/or filing

•

Final actions and case closure

Occurs when a case will be subject

• ‘Prevention opportunities and

to no further action because all

responsibilities’ in the

‘Specialist

reasonable lines of enquiry have

accreditation, case management

been exhausted without result or the

and assurance’ chapter)

matter has proceeded to a resolution

in the court system or by alternative

action. As per the tiered training

model only Level 4 trained staff can

file CP cases.

All steps

•

Responsibilities for victims

Consider Police responsibilities

for victims throughout the

investigation.

As at 15/07/2020

Page 14 of 39

link to page 10 link to page 16 link to page 17

Child protection investigation policy and

procedures,

Continued...

Initial actions and safety assessment

Introduction

Police receive reports of child safety concerns through a variety of reporting channels,

such as telephone calls to Communications Centres, the watchhouse counter, or police

become concerned when attending an incident. In every case, the priority is to ensure

the child's immediate safety. You should also ensure that your local

CPP contact is

notified as soon as practicable.

Procedure when a report of concern is received

Follow these steps when initially responding to reports of child safety concerns.

Step

Action

1

Obtain brief details of what the reported concern is about to enable a risk

assessment to be completed to determine the appropriate initial response.

This should include:

• personal details of the informant, complainant and/or the child

• brief circumstances of concern/complaint

• brief details of timings and about the scene

• offender's details.

Do not question the child in depth at this stage.

• If the child has disclosed sexual or physical assaults to an adult, take this

person’s details and use what they say to form the basis of information for

the notification.

DO NOT ask the child again what has happened to them if

a clear disclosure has already been made and an adult present can give

you the information.

• If it is unclear what the child has said

and:

- there are no urgent safety issues,

DO NOT question the child any

further. Take details from the informant and forward necessary

correspondence for enquiries to be made

- it is absolutely necessary to speak to the child to ascertain their safety,

ask open ended questions, e.g. "Tell me what happened?" "When did

that happen?"

DO NOT continue to question the child if it becomes clear

while speaking to them that an offence has occurred.

2

Consider if there are immediate concerns for the child’s care or safety

requiring immediate intervention. (Family violence information may be

relevant to determining the risk). Determine the appropriate action to ensure

immediate safety, e.g.:

• arrest if there is sufficient evidence of an offence and remove the offender

from the home

• if there is insufficient evidence to arrest and charge the offender, consider

issuing a

Police safety order which would remove the person

• removal of the child (see

Options for removing a child below)

•

manage children found in clandestine laboratories.

If the report is received at a watchhouse, immediately contact a supervisor or

child protection investigator to determine what intervention is required.

3

Consider whether Iwi, Pacific or Ethnic Liaison Officers attendance could be

beneficial.

4

Record details of the case in NIA. Regardless of any other offence/response

code used,

Code 6C must be entered in NIA to indicate that the attendance

related to a report of concern about a child.

As at 15/07/2020

Page 15 of 39

link to page 10

Child protection investigation policy and

procedures,

Continued...

5

If the situation does not require immediate intervention:

• complete a CPP referral form (POL 350 in Police Forms> Child Protection)

and email to [email address] and your local

Police CPP contact for

further investigation (use CPP email address). This referral should be

completed by the attending officer before going off duty on the day of the

report

• follow the

Family harm policy and procedures if family violence was

involved.

6

Take necessary initial actions relating to criminal investigations to:

• preserve crime scene and physical evidence where relevant

• secure witnesses

• locate and detain suspected offenders.

7

When circumstances permit, provide parents and caregivers with a copy of the

pamphlet

'When Police visit about your child's safety'. This provides

information about why Police are talking to them, what happens next, what

will happen with a case and who they can contact for further information.

Options for removing a child

Remove a child when:

• it is not safe to leave them there or you believe, on reasonable grounds that if left,

they will suffer, or are likely to suffer, ill treatment, neglect, deprivation, abuse or

harm, and

• there is no other practical means of ensuring their safety.

Powers of removal

If you believe that removing the child is necessary, you may enter and search:

Power

Description

Without a

This is a Police power and can only be invoked when police believe

warrant

on reasonable grounds it is critically necessary to remove that

child to prevent injury or death.

(s42 Oranga

Tamariki Act 1989 When exercising the power you must:

(OTA))

• produce evidence of identity, and

• disclose that your powers are being exercised under s(

s42(2))

and

• a written report must be made to Commissioner of Police within

3 days of power being exercised (s42(3)). Complete

notification "Child/Young Person Arrest/removal" in Microsoft

Outlook to comply with this requirement.

With a place of

OT staff normally obtain place of safety warrants, although police

safety warrant

may assist with executing the warrant. (While police may apply

for such a warrant it would be highly unusual to do so).

(s39 OTA)

On entry, police (or social worker) may remove the child if they

still believe on reasonable grounds that the child has suffered, or

is likely to suffer, ill-treatment, serious neglect, abuse, serious

deprivation, or serious harm.

With a warrant

When the court is satisfied a child is in need of care and

to remove

protection, it may issue a warrant for the child’s removal from any

place and for them to be put in Oranga Tamariki care. These

(s40 OTA)

warrants are sought by when there are ongoing care and

protection concerns.

As at 15/07/2020

Page 16 of 39

Child protection investigation policy and

procedures,

Continued...

Managing children found in clandestine laboratories

Where children or young persons are located by police in a clandestine laboratory during

a planned termination phase of an operation or in the course of regular police duties,

Oranga Tamariki must be notified under the

Child Protection Protocol Joint Operating

Procedures.

Neglect as defined in the Protocol, includes situations where a child or young person is

found to have been exposed to the illicit drug manufacturing process or an environment

where volatile, toxic or flammable chemicals have been used or stored for the purpose of

manufacturing illicit drugs.

The

Joint Standard Operating Procedures for Children and Young Persons in Clandestine

Laboratories outlines full roles and responsibilities for Police and Oranga Tamariki staff.

They also outline emergency powers for unplanned situations where children and young

persons are located inside clandestine laboratories.

As at 15/07/2020

Page 17 of 39

link to page 11 link to page 11 link to page 21

Child protection investigation policy and

procedures,

Continued...

Consultation and initial joint investigation planning with

Oranga Tamariki

Consultation procedures

This table outlines the steps to be taken by the Police CPP contact person when receiving

notice of a child abuse concern.

Step

Action (by Police CPP contact person unless otherwise stated)

1

Review the accuracy and quality of the information provided in the referral

and any initial actions already undertaken (e.g. the child’s removal and/or the

offender’s arrest). Arrange any further necessary inquiries.

2

Make an initial assessment of the seriousness of the case (see

Determining

seriousness of physical abuse).

If the case falls within the guidelines of the

CPP (physical, sexual, neglect)

complete and email a CPP referral form (Police Forms>Child Protection) to the

Oranga Tamariki National Call Centre ([email address]) and cc your local

CPP EMAIL address. (See

Making referrals to Oranga Tamariki for when and

how to make referrals).

If there is any doubt as to the degree of seriousness and whether t

he CPP

applies, the case should be referred for further discussion with Oranga

Tamariki.

3

The CPP contacts from Police and Oranga Tamariki at a local level consult

about the CPP referral. This consultation may occur at the same time as the

case was referred. This consultation should be clearly evidenced and recorded

on the nationally agreed template in the respective case management

systems.

The consultation should:

• share information or intelligence about the particular case

• confirm if the referral meets the threshold of the CPP

• discuss any immediate action required to secure the immediate safety of

the child

• consider whether a multi-agency approach is required.

4

The CPP contacts from Oranga Tamariki and Police discuss the case and agree

on an Initial Joint Investigation Plan (IJIP). The purpose of the IJIP is to

ensure that we work together to secure the child’s immediate safety and

ensure any evidence is collected.

Oranga Tamariki record the IJIP on the nationally agreed template and

forward a copy to Police as soon as practicable. This should be done within 24

hours. In some circumstances it may be agreed between the consulting

Oranga Tamariki and Police CPP contacts that Police record the IJIP.

In all cases, necessary steps must be put in place immediately to secure the

child's safety and any other children that may be at risk.

As at 15/07/2020

Page 18 of 39

Child protection investigation policy and

procedures,

Continued...

5

After a case is confirmed as a CPP case

• update NIA and note it is a CPP case

• prioritise and assign the case to the most appropriate investigator, taking

into account the recommended maximum case assignments for

investigators. Cases awaiting assignment must be reviewed at least once a

month and any identified concerns or risks while the case is waiting,

appropriately managed. (See the

Child Protection - Specialist accreditation,

case management and assurance chapter for more information).

6

CPP case record:

• Oranga Tamariki create a CPP record in their electronic case management

system (CYRAS).

• Police confirm that the case is recorded as a CPP case in their electronic

case management system (NIA).

7

Following the agreement of an initial joint investigation plan (IJIP) the tasks

outlined in the IJIP

will be reviewed via the CPP meeting to ensure they have

been completed as agreed. The CPP contacts must communicate any

significant updates which occur in the intervening period.

Note that only cases closed by

both agencies can be removed from the CPP

case list at a CPP meeting.

8

If the case is not confirmed as a CPP case:

• Police will record the case in NIA case management system and record the

reason why the referral was not confirmed as a CPP case

• Police may continue an investigation role outside of the CPP process to

determine if there is any on-going role in terms of prevention.

Initial joint investigation plans

Agreement on the Initial Joint Investigation Plan

The CPP contacts from Oranga Tamariki and Police will discuss the case and agree on an

Initial Joint Investigation Plan (IJIP). Its purpose is to ensure that we work together to

secure the child’s immediate safety and ensure any evidence is collected.

Oranga Tamariki will record the IJIP on the nationally agreed template and forward a

copy to Police as soon as practicable. This should be done within 24 hours. In some

circumstances it may be agreed between the consulting Oranga Tamariki and Police CPP

contacts that Police record the IJIP.

The IJIP must consider the following:

• the immediate safety of the child involved and any other children who may be

identified as being at risk

• referral to a medical practitioner and authority to do so

• the management of the initial interview with the child

• if a joint visit is required due to the risk of further offending, loss of evidence, the

likelihood of the alleged offender being hostile, or any concerns for staff safety

• collection of any physical evidence such as photographs

• any further actions agreed for Police and/or Oranga Tamariki including consideration

as to whether a multi-agency approach is required.

The tasks outlined in the IJIP

will be reviewed via the CPP meeting to ensure they have

been completed as agreed. The CPP contacts must communicate any significant updates

which occur in the intervening period.

Updating initial joint investigation plans

As at 15/07/2020

Page 19 of 39

link to page 21

Child protection investigation policy and

procedures,

Continued...

The tasks outlined in the IJIP

will be reviewed via the CPP meeting to ensure they have

been completed as agreed. The CPP contacts must communicate any significant updates

which occur in the intervening period.

As the criminal investigation progresses for CPP cases, case updates and further tasks

will be recorded in the respective case management systems and in the on-going case

investigation plan. The case investigation plans must be updated as necessary to ensure

that appropriate interventions are maintained. Ongoing consultation between Police and

Oranga Tamariki is crucial for the effectiveness of the CPP and for the victim and their

family to receive the best service from both agencies.

CPP meeting to discuss cases

CPP meetings will be held at least monthly or more frequently as required between the

Oranga Tamariki and Police CPP contacts.

Oranga Tamariki will make the CPP Case List (Te Pakoro Report 100) available to Police

prior to the CPP meeting.

In order to ensure that the CPP meetings are productive and focused, the following

standing agenda items have been agreed:

• review the CPP Case List to ensure all cases are recorded

• confirm both agencies have a copy of the agreed IJIP and all of the agreed actions

from the IJIPs have been completed

• case update on the progress of the Oranga Tamariki investigations

• case update on the progress of the Police investigations

• record any further tasks

• advise any case investigations which have been closed and the outcomes

• discussion of any concerns or issues.

One set of agreed formal minutes, using the meeting minute template (word document),

must be taken for each meeting held. These minutes will be shared between the two

parties, agreed and retained as per the CPP.

Cases falling outside of the Child Protection Protocol Joint Operating

Procedures

Not all care and protection concerns require a response under the

CPP. The CPP sets out

the criteria for those that do. If the concerns do not meet the CPP threshold, this does

not mean that the role of Police and Oranga Tamariki is at an end.

Oranga Tamariki will complete an assessment of care and protection concerns. Police

will ensure that any family violence cases that do not fall within the CPP threshold are

referred to the District/Area Family Harm Coordinator or equivalent for follow up.

There will be some cases that are initially identified as CPP, but new information means

the CPP threshold is no longer met, or the criminal investigation cannot be progressed.

As above, this does not mean that that the role of Police and Oranga Tamariki is at an

end, but that the CPP is no longer the correct process for investigation.

See als

o Making referrals to Oranga Tamariki for further information about when and

how referrals to Oranga Tamariki or other Police services should be made.

As at 15/07/2020

Page 20 of 39

link to page 11 link to page 11 link to page 18

Child protection investigation policy and

procedures,

Continued...

Making referrals to Oranga Tamariki

Types of cases requiring referral to Oranga Tamariki

Police are informed of a variety of situations requiring notification to Oranga Tamariki

that a child may be at risk. These cases fall into four general categories.

Category

Examples

Child abuse

• physical abuse

• sexual abuse

• neglect

• sexual imaging of child

Family violence

• where there is a direct offence against a child or young

person

• neglect of child or young person (as pe

r CPP definition of

neglect), or

• anytime where after an investigation has taken place that

factors indicate a concern for safety that warrants statutory

intervention.

(See “Child risk information and Reports of Concern” (ROC) to

Oranga Tamariki in the

Family harm policy and procedures).

Environment /

• clan lab

neglect

• unsafe home

• car crash

• abandonment

• cyber crime exploiting children

Other criminal

• child identified as a suspect / offender

activity

Many of these concerns, other than those meeting the

CPP, can be dealt with outside of

the CPP processes (see

Consultation and initial joint investigation planning with Oranga

Tamariki in these procedures).

Referral process varies depending on case type

This table outlines how referrals to Oranga Tamariki should be made for different cases.

Category of

How should referrals to Oranga Tamariki be made?

referral

As at 15/07/2020

Page 21 of 39

link to page 10

Child protection investigation policy and

procedures,

Continued...

Child Protection

CPP referrals from Police to Oranga Tamariki can be made in

Protocol cases –

four ways:

criminal offence

• a phone call between local staff, followed by an electronic CPP

against a child

referral form (POL 350 in Police Forms>Child Protection)

• electronically using the CPP referral form

• electronically forwarding the CPP referral form between the

Oranga Tamariki National Contact Centre and Police Comms

Centre’ Crime Reporting Line

• via the OnDuty Family Harm mobility solution.

The method adopted will depend on the initial point of contact

and required urgency of response. E.g. if the situation does not

require immediate intervention, email (using the CPP email

address) a completed CPP referral form to your CPP contact for

further investigation before going off duty on the day of the

report.

Note that if Oranga Tamariki were involved in immediate

actions to ensure child safety, there is no requirement for the

CPP contact person to forward the CPP referral to the Oranga

Tamariki National Contact Centre.

Family violence

Where there is repeated exposure to family violence or concerns

referrals

exists which do not meet the CPP threshold, an OT Report of

Concern (ROC) can be made. If concerns arises at a Family

Harm event, this should be fully outlined in the investigation

narrative and discussed at the multi-agency table. A ROC can be

initiated off the table via the OT representative.

Note: If there is evidence of serious child abuse, the CPP

referral process, using the Pol 350, applies.

Environment /

The Oranga Tamariki National Call Centre (NCC) should be

neglect referrals

informed of situations where concerns held for the well being of

the child due to their environment may require a Oranga

Tamariki risk assessment. This can be by:

• phone call to

0508 family

• email to NCC via email address

[email address]

Other criminal

This is managed through Police Youth Services on completion of

activity

the investigation case file for an offender identified as a child.

Minor or trivial

Minor or trivial cases do not have to be referred to Oranga

cases

Tamariki.

Referral of historic cases to Oranga Tamariki

When a report of historic child abuse is received, a risk assessment must be completed

to assess the risk the offender may currently pose to children. The assessment should

consider (amongst other factors):

• currency and timeframes of offending

• the suspect's current access to children

• nature of offending, e.g. preferential or opportunist sexual offender

• multiple victims

• occupational, recreational or secondary connection to children, e.g. school teacher,

volunteer groups, or sports coaches.

Even though the victim is now an adult it may be appropriate to consult with Oranga

Tamariki to resolve any current care and protection concerns of children at risk from the

alleged offender.

As at 15/07/2020

Page 22 of 39

Child protection investigation policy and

procedures,

Continued...

Interviewing victims, witnesses and suspects

Interviewing children in child abuse investigations

All interviews of child abuse victims or of childwitnesses to serious crime must be

conducted carried out according to the

Specialist Child Witness Interview Guide by

specially trained specialist child witness interviewers (SCWI).

The

Specialist Child Witness Interview Guide details policy and guidelines relating to

specialist child witness interviews:

• agreed jointly by Oranga Tamariki and Police

• for trained specialist child witness interviewers of Oranga Tamariki and the Police,

and their supervisors and managers.

The policy and guidelines detailed in the Guide ensure specialist child witness interviews

are conducted and recorded in accordance with the

Evidence Act 2006 and the

Evidence

Regulations 2007 and that best practice is maintained.

Interviewing adult witnesses

When interviewing adult witnesses in child abuse investigations, follow:

•

Investigative interviewing witness guide, and

• additional procedures in

Investigative interviewing - witnesses requiring special

consideration (e.g. when the witness has suffered trauma, fears intimidation, or

requires an interpreter).

Interviewing suspects

When interviewing suspects in child abuse investigations, follow the

Investigative

interviewing suspect guide including procedures for suspects requiring special

consideration (e.g. because of age, disability, disorder or impairment, or where English is

a second language).

As at 15/07/2020

Page 23 of 39

link to page 18 link to page 18 link to page 25 link to page 25 link to page 25

Child protection investigation policy and

procedures,

Continued...

Medical forensic examinations

Primary objective of the examination

The child's well being and safety is paramount. Therefore, the primary objective of a

medical forensic examination is the victim's physical, sexual and mental health, and

safety. Of secondary importance is the opportunity to collect trace evidence. The medical

forensic examination should be promoted to the victim and their family in this way.

Timing of examinations

The timing for a child's medical examination should be considered when the

initial joint

investigation plan is agreed between the Police and Oranga Tamariki contact persons.

The urgency of a medical examination will depend on the circumstances in a particular

case. Always consult with a

specialist medical practitioner when making decisions about

the timing and nature of examinations.

Type of case Timing

Acute sexual

A specialist medical practitioner must be contacted as soon as

abuse cases

possible. Capturing forensic evidence that may disappear, using a

medical examination kit and/or toxicology kit, is particularly important

in the first 7 days after sexual abuse.

If three or four days have passed since the abuse, the examination

may not be as urgent, but should still be considered, primarily for the

victim's wellbeing and for trace evidence capture. This recommended

course of action should be discussed with the victim, their family and

the specialist medical practitioner.

For further information see “Medical forensic examinations” in the

Adult sexual assault investigation policy and procedures.

Acute physical These cases often come to Police attention due to medical intervention

abuse

already occurring at hospitals or doctors surgeries. In other cases, the

examination should be arranged as soon as possible in consultation

with the victim, their family and the specialist medical practitioner.

Bruises and other injuries may take a number of days to best appear

and a further assessment should be made at the follow-up medical

appointment. Consult with the specialist medical practitioner as to

when this should be arranged.

Non acute /

These are non-urgent cases where the medical response can be

therapeutic

arranged at a time convenient to the medical practitioner, the child

and their family. In non acute sexual abuse cases there is little

expectation of locating forensic evidence but the medical examination

is necessary for the assurance of the victim and family (e.g. that there

is no permanent injury, pregnancy, sexually transmitted infections).

In older physical abuse cases a medical examination may be required

to verify concerns of past injury that may be detected by examination

or X-ray.

Arranging the medical

Where a medical examination of a child is considered necessary, refer the child to a

specialist medical practitioner for that examination.

As at 15/07/2020

Page 24 of 39

link to page 9

Child protection investigation policy and

procedures,

Continued...

The medical practitioner must be consulted as to the time and type of examination

required, based on the information received from the child/informant. Except for urgent

medical or forensic reasons, arrange the examination at a time and place that is least

stressful to the child. Also consider religious or cultural sensitivities when conducting the

medical examination.

The medical examination should be completed in a

child centred timeframe and by an

appropriate medical practitioner. This will avoid causing unnecessary trauma by having

to re-examine a child previously examined by a practitioner without specialist knowledge

and expertise.

Specialist medical practitioners to conduct examinations

In cases of serious child abuse, doctors who are DSAC (Doctors for Sexual Abuse Care

Incorporated) trained are the preferred specialist.

Whether the child victim is medically forensically examined by a specialist paediatric or a

general medical examiner varies around New Zealand. When briefing the medical

practitioner about the circumstances and timing of the medical examination, canvas with

them the question of who is best to conduct the examination. The decision is made by

the medical practitioner taking into account the child's age, their physical development

and the nature of their injuries.

Support during the examination

A parent or legal guardian who is not the suspect or another competent adult with whom

the child is familiar should accompany the child for the examination, unless that is not

appropriate in the circumstances.

Examination venues

Medical examinations should be conducted at a Sexual Assault Assessment & Treatment

Service's (SAATS's) recognised venue, e.g. paediatric clinics of District Health Boards or

doctors' clinics. They must not take place at Police premises unless purpose built

facilities exist which are forensically safe environments.

Examination procedures

The police role in a medical examination of child victims of serious physical and sexual

abuse are essentially the same as for adult victims. Follow the procedures "Before

conducting medical examinations" and "Examination procedures" in the ‘Medical forensic

examinations’ section of the

Adult sexual assault investigation policy and procedures

when preparing for and conducting medical forensic examinations of child victims.

Photographing injuries

The recording of physical injuries is important to corroborate an account of abuse.

Medical practitioners will identify during their examination any injuries that should be

photographed and may decide to sensitively take these during the examination. Police

can also take photographs of the victim's physical injuries with the victim's or parent/

guardian's full consent. An appropriately trained Police photographer should be used for

this.

Consult with the specialist medical practitioner as to when photographs should be taken.

Bruises and other injuries may take a number of days to appear so consider the benefits

of taking a series of photographs to record the changes.

A support person should be present to support the victim while photographs are being

taken and afterwards.

As at 15/07/2020

Page 25 of 39

link to page 29

Child protection investigation policy and

procedures,

Continued...

Evidence gathering and assessment

Police responsibility for criminal investigations

NZ Police is the agency responsible for the investigation of any criminal offending. They

have a statutory obligation to investigate any report they receive alleging that a child

has been, or is likely to be, harmed (whether physically, emotionally, or sexually), ill-

treated, abused, neglected, or deprived (

s17 OT Act 1989).

While the investigation process for child abuse complaints has many similarities with

other criminal enquiries there are subtle differences such as the power imbalance

between the child and the offender as well as the subsequent impact and consequences

of the abuse on the victim.

Investigators need understanding and sensitivity in all interactions with the victim and

their families. They also need an appreciation of offenders' motivation. For example,

does a sexual offender appear opportunistic or preferential in nature? Is the event well

planned, ill-conceived or stumbling? Is what appears to be a minor physical assault a

pattern of increasing violence?

As for any other criminal investigation, child abuse investigations must be undertaken in

a way that evidence gathered is admissible in court proceedings. Correct procedures

must be followed to ensure the strongest possible case can be put before the courts to

hold an offender accountable. This will increase the likelihood of a successful prosecution

and enhance outcomes for the victim, their family and the wider community.

Crime scene examination

Follow standard investigation procedures detailed in the Police Manual for:

•

crime scene examination

• gathering and securing

physical and forensic evidence.

Consider all investigative opportunities

Also consider other investigative opportunities, such as history of family violence, area

canvas, location of further witnesses, propensity (similar fact) evidence, Intelligence

office input (e.g. prison releases, known sex offenders, similar crime etc), media

releases, contact with the Police

Behavioural Science Unit and other potential case

circumstances.

See also:

•

Hospital admissions for non- accidental injuries or neglect in this chapter

• the Child protection -

'Mass allegation investigation' and

'Investigating online offences

against children' for information about managing:

- multiple allegations of serious child abuse committed by the same person or a

connected group of people

- allegations associated with education settings

- online offences investigations involving children, including indecent communication

with a young person under 16

Exhibits

Follow standard investigation procedures for:

• locating, recording and photographing exhibits in situ

• securing, labelling and packaging, handling and retention of exhibits

• analysis, assessment and court presentation

• final action, i.e. appropriate return, disposal or destruction.

As at 15/07/2020

Page 26 of 39

Child protection investigation policy and

procedures,

Continued...

Always consider the potential sensitivity of exhibits for scientific assessment, especially

those cases of a sexual nature. Sound handling processes must be adhered to, recorded

and able to be outlined.

Dealing with suspects

Identifying and locating suspects