Organisational Capability Governance Group

Cover Sheet

Reference

Organisational Capability Governance Group

Cover Sheet

Reference OCGG/20/32

[Obtained from the Executive Services team]

Paper title

Fleeing Driver Events: Investigation Practice Guide

Sponsor

Deputy Commissioner Glenn Dunbier

Presenter/s

Assistant Commissioner Sandra Venables

Prepared by

Nigel Thomson, Public Safety Team, Christchurch

Kelly Larsen, Fleeing Driver Programme Manager

Meeting date Tuesday 17 November 2020

[Paper is due with ES six working days before scheduled meeting date]

1982 to Ti Lamusse

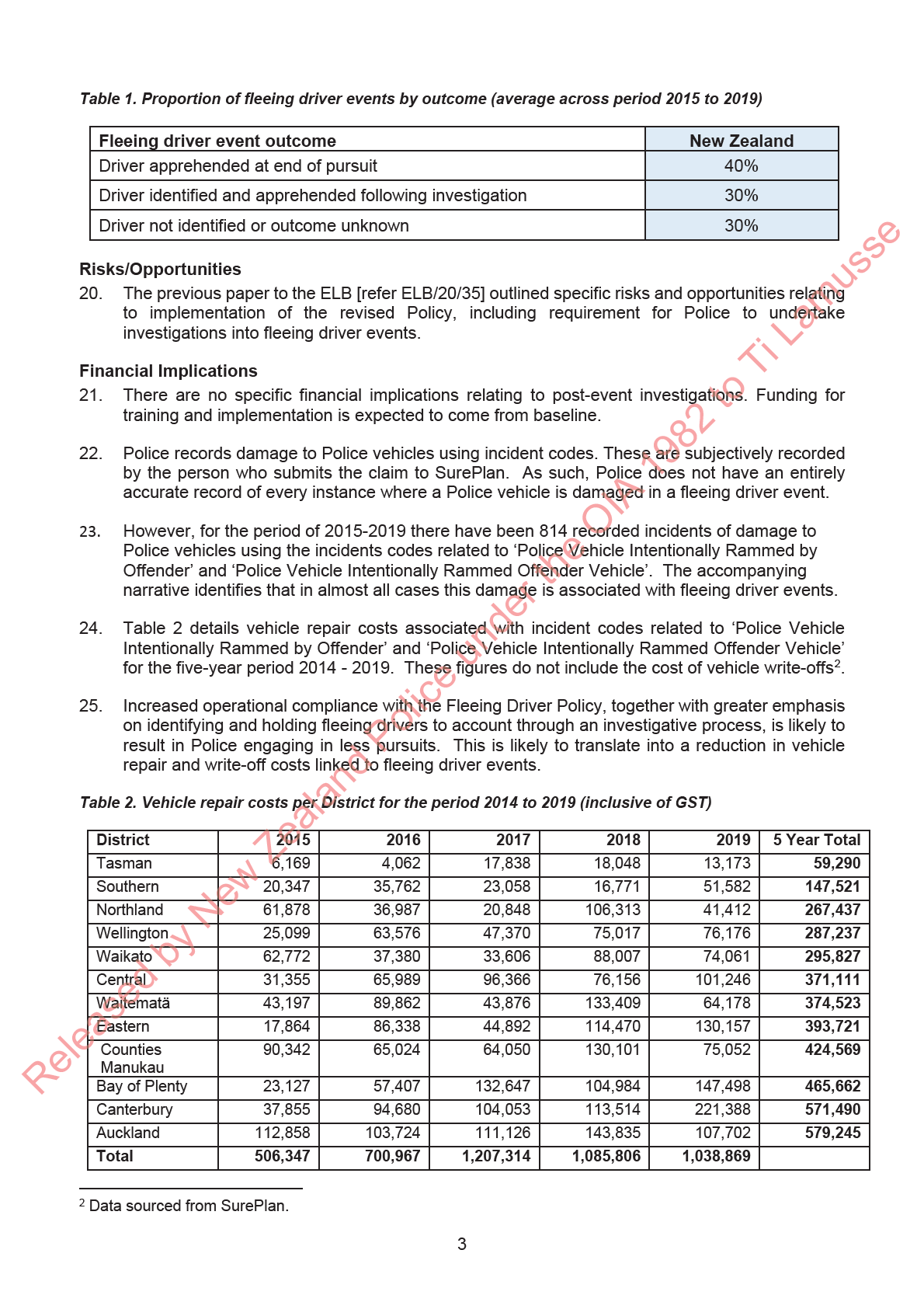

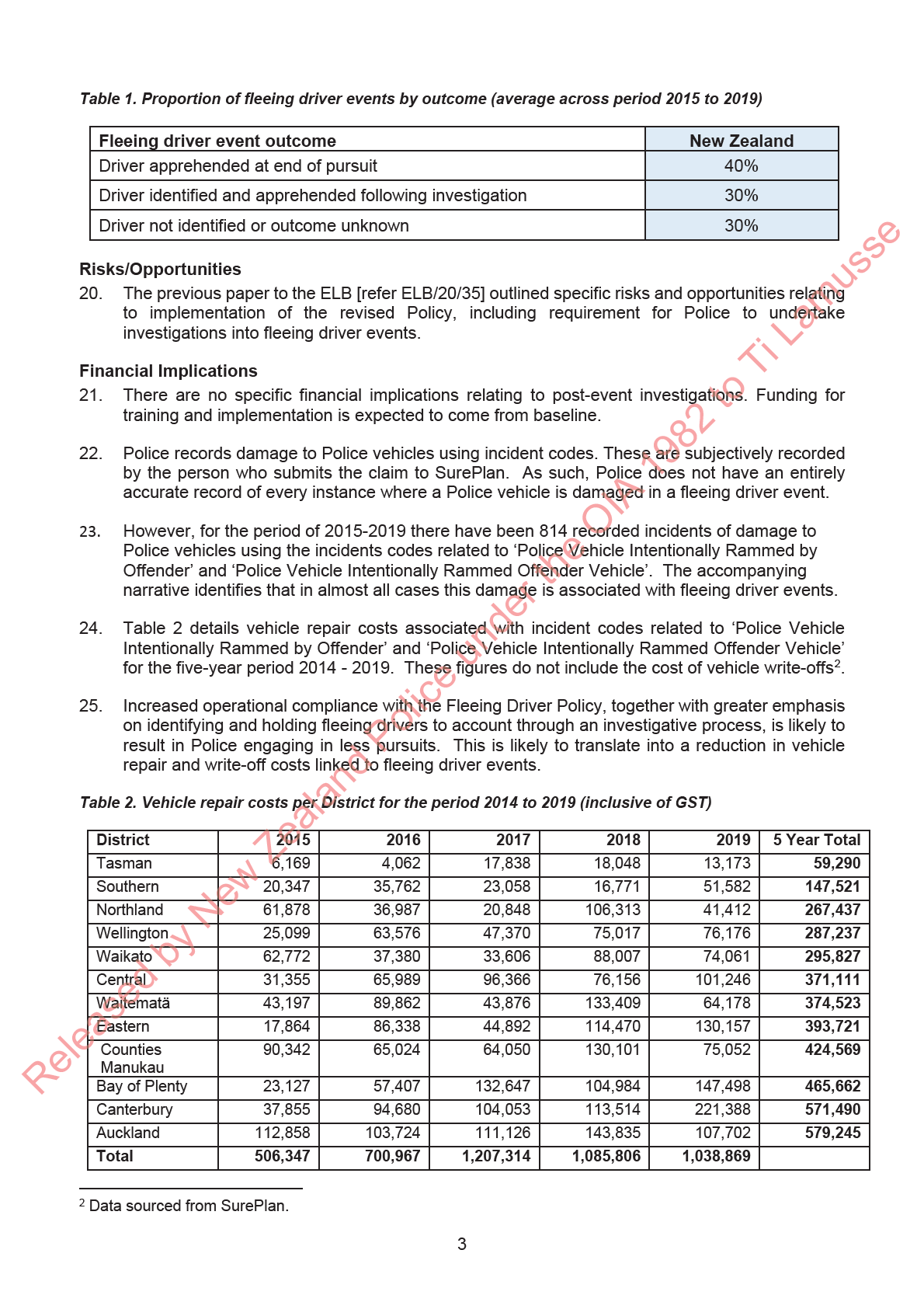

Consultation required

Unless specifically directed by the paper’s Sponsor, the paper should be presented to at least one of the four sub

governance groups in the first instance, using the appropriate governance group paper template.

If the contents of this paper are such that they are to be presented to the SLB only, consultation may stil need to be

undertaken with other work groups / service centres / districts to ensure their views have been sought and are accurately

reflected in this paper.

For consultation purposes, please use the following group email addresses: ‘DL_Assistant Commissioners’ and

‘DL_GovernanceConsultation’. These email lists are frequently updated.

Please double click the boxes to tick which groups / individuals have been consulted regarding this paper and include their

feedback in the Feedback Received section.

Police under the OIA

Tick Group / individual

Specify, if required

Assistant Commissioners

Executive Directors

Consultation Group (SLB Papers)

District staff (specify)

External (specify)

Other (specify)

While a sponsor can exempt a paper from seeking consultation this should be an extremely rare occurrence. If your

Sponsor deems consultation to be unnecessary, a full explanation must be provided below:

by New Zealand

TRACKING:

(for ES use only)

Released

Organisational Capability Governance Group

Reference

OCGG/20/32

Title

Fleeing Driver Events: Investigation Practice Guide

10 November 2020

Purpose

1.

The purpose of this paper is to provide the Strategic Leadership Board (SLB) with a nationally

consistent practice guide for post-event investigations following fleeing driver events.

2.

This information will assist the SLB in considering and approving proposed revisions to the

Fleeing Driver Policy (the Policy), specifically the requirement for mandatory post-event

investigations to ensure driver accountability.

Executive Summary

3.

The Executive Leadership Board (ELB) considered proposed revisions to the Policy on 18 May

2020 [refer ELB/20/35].

1982 to Ti Lamusse

4.

Arising from this discussion, the ELB requested the development of a nationally consistent best

practice process for post-event investigations following fleeing driver events.

5.

A hui was undertaken in July 2020 with a range of District staff to discuss what a best practice

investigation process looked like, to ensure that fleeing drivers and any person enabling this

behaviour, are held to account.

6.

The proposed Fleeing Driver: Investigation Practice Guide (Appendix A) is the result of those

discussions, and wider internal consultation.

7.

The overarching principle of the Fleeing Driver Policy is that public, vehicle occupants(s) and

Police employee safety takes precedence over the immediate apprehension of a fleeing driver.

8.

A key principle of the Policy is that an inquiry is preferred over the com

Police under the OIA mencement of a pursuit.

9.

Increased emphasis on using investigations rather than pursuits to identify and hold fleeing

drivers to account will realign operational practice with policy and wil have safety benefits. It is

likely that fewer pursuits wil result in fewer injuries and deaths from fleeing driver events.

10. This aligns with our vision and our purpose, as well as our goals of safe roads and safe

communities. While there is a risk that fewer pursuits may lead to a decrease in the overall

apprehension rate, this is outweighed by the safety benefits and the comparatively high

apprehension rate currently achieved through post-event investigations.

11. It is recommended the OCGG notes this information when considering and endorsing the

by New Zealand

proposed revisions to the Policy, specifically the requirement for mandatory post-event

investigations.

Fleeing Driver Policy – Mandatory Post-Event Investigations

12. Proposed revisions to the Fleeing Driver Policy give effect to the agreed recommendations

detailed in the joint Independent Police Conduct Authority and New Zealand Police thematic

Released

review;

Fleeing Drivers in New Zealand: A collaborative review of events, practices, and

procedures (the Review)

.

1

13. The Review recommends Police strengthens oversight and post-event accountability processes

for fleeing driver events (Recommendation 5). This includes introducing a requirement for officers

to record a fleeing driver event as either resulting in an arrest (K9), or requiring further

investigation (K6), where it has not been possible to identify or apprehend the driver. This would

arise in situations where Police signal a driver to stop, the driver fails to stop or remain stopped,

and:

• Of icers elect not to initiate a pursuit

• Of icers initiate, but then abandon a pursuit

• Of icers initiate a pursuit, but the driver subsequently abandons the vehicle and is unable

to be located.

14. The proposed Policy revisions emphasise that where a fleeing driver event does not result in an

apprehension, there must be a robust investigation to identify the driver and hold them to account.

Where immediate follow up is required, the Pursuit Controller wil direct an available supervisor

to lead these enquiries. Follow-up enquiries may include obtaining vehicle registration details

(e.g. s.6(c)

locating the vehicle, or speaking with the owner or hirer of the vehicle to obtain

information which may lead to the identification of the driver.

1982 to Ti Lamusse

15. The rationale for this change is that by requiring officers to undertake robust investigations, rather

than initiating or continuing pursuits Police wil manage high-risk drivers in a way that:

•

reduces the number of pursuits;

•

increases public and staf safety;

•

increases fleeing driver accountability; and

•

enhances public trust and confidence.

Fleeing Driver Event Investigations

16. The ELB requested the development of a nationally consistent investigation practice to ensure

an effective response to fleeing driver events.

17. A hui was undertaken in July 2020 with a range of District staff to discuss what a best practice

Police under the OIA

investigation process in relation to fleeing drivers needed to encompass. Participants agreed the

current Fleeing Driver Policy was robust. They also agreed with the need to strengthen the post

event investigations and establish nationally consistent best practice to ensure that fleeing

drivers, and anyone enabling this behaviour, are held to account.

18. An increased emphasis on using investigations rather than pursuits to identify and hold fleeing

drivers to account wil have safety benefits. There is a higher likelihood of death and serious

injuries occurring during pursuits compared with other Police responses (besides firearms) with,

on average, six and 41 per 1,000 events resulting in fatal and serious injuries respectively.1

Therefore, it is likely that fewer pursuits wil result in fewer injuries and deaths from fleeing driver

events.

by New Zealand

19. While there is a risk that fewer pursuits may lead to a decrease in the overall apprehension rate,

this is outweighed by potential safety benefits and the relatively high apprehension rate already

achieved through post-event investigations [refer Table 1].

Released

1 Based on number of fleeing driver events involving fatal and serious injuries per 1,000 events by year for the

period 2005 to 2017 from the joint Independent Police Conduct Authority and New Zealand Police thematic

review;

Fleeing Drivers in New Zealand: A collaborative review of events, practices, and procedures.

2

Resourcing / Staff Implications

26. The requirement to undertake investigations into all fleeing driver events may result in staff

allocating more time to investigations. However, it is anticipated the revised Policy wil not have

significant resourcing or people implications overall.

IT Implications

27. There are no anticipated IT implications as the CARD system and policies around the coding and

resulting of fleeing driver events have already been implemented.

Māori, Pacific and Ethnic Peoples

28. Police acknowledges there are a disproportionate number of young Māori men involved in fleeing

driver events. Increased emphasis on using investigations (rather than pursuits) to identify and

hold fleeing drivers to account may improve safety outcomes for this demographic due to fewer

serious injuries and deaths.

29. However, this may stil result in a disproportionate effect for Māori. For example, an investigation

resulting in criminal charges may be the entry point into the criminal justice system.

30. In many instances it wil be appropriate to take prosecutorial action. Consideration ought to be

1982 to Ti Lamusse

given to supported resolutions such as alternative justice pathways for young or first-time

offenders to address potential inequities.

Alignment with strategic priorities

31. Increased emphasis on identifying and holding fleeing drivers to account through a robust

investigation process is likely to reduce the number of pursuits, which wil increase the safety of

the public and our people. This aligns with our vis on and our purpose, as well as our goals of

safe roads and safe communities.

32. Ensuring fleeing drivers are held to account aligns with our functions of maintaining public safety

and law enforcement, thereby ensuring that we have the trust and confidence of all.

Legislative Implications

33. There are no anticipated legislation implications.

Police under the OIA

Health and Safety Implications

34. An increased focus on investigations rather than pursuits to hold fleeing drivers to account is

likely to reduce health and safety risks for our people, as a result of engaging in fewer pursuits.

This wil ensure our people are safe and feel safe.

Training and Implementation Implications

35. Development and delivery of appropriate, effective training wil be required to communicate the

requirement for post-event investigations to be completed, which adhere to the investigation

process developed.

by New Zealand

Case Management

36 Case management processes are applied to all cases. When an occurrence is first created in

NIA, the system wil determine from the offence or incident code the category of the offence or

incident.

37. Current

Released ly offences related to fleeing driver events are assigned a category of 9, which includes

all tasks/incidents and minor traffic matters.

38. Only categories 1-4 are included within the scope of the case management programme

reporting framework. These categories are:

4

• 1 – Mandatory

• 2 – Critical

• 3 – Priority

• 4 – Volume

39. To ensure the investigation of fleeing driver events is prioritised against competing demand, it

is recommended that all offences relating to fleeing drivers are assigned a case category of 2 -

Critical.

District Implications

40. Effective District prioritisation and oversight wil be required to ensure post-event investigations

are conducted in a timely manner and completed to a high standard.

41. It is dif icult to quantify what impact (if any) the requirement to complete post-event investigations

wil have in terms of demand and resourcing. Feedback from some Road Policing Managers is

that they don’t anticipate this will result in a significant increase in investigation time. In contrast,

other Districts believe the investigation process wil have capacity and capab lity impacts.

42. Work is currently underway to develop reporting to support Districts to monitor the status of

fleeing driver investigations, which will help ensure accountability

1982 to Ti Lamusse

Implications for other Agencies

43. There are no specific implications for other agencies.

Public Relations

44. Following the approval of the proposed investigation practice guide, Media and Communications,

together with the Fleeing Driver Action Plan Steering Group, wil develop an appropriate

communication strategy to convey this information to staff nationally. Delivery of Fleeing Driver

investigation training could be facilitated through a mandated course in My Learning in My Police.

Consultation

45. As a result of the hui, the Fleeing Drivers: Investigation Practice Guide was developed and

circulated to the working group for review and feedback.

Police under the OIA

46. This paper and the proposed investigation process were circulated to the Fleeing Driver Action

Plan Steering Group, before being sent out for wider consultation via the Consultation Group

(ELB&SLT Papers) distribution list.

47. Feedback was received from Counties Manukau, Waitemata, Eastern, Bay of Plenty and

Central districts, as well as from Policy Group, Assurance Group and the Of ice of the

Commissioner. Feedback is summarised in Appendix A.

Recommendations

It is recommended the OCGG:

by New Zealand

(i)

Note that ELB requested development of a nationally consistent investigation process to hold

fleeing drivers to account.

(ii)

Note that this paper is intended to assist the ELT in considering and approving the revised Policy

and should be considered alongside the paper discussed on 18 May 2020 [refer ELB/20/35].

Released

(iii)

Endorse the Fleeing Driver Event: Investigation Practice Guide (Appendix A).

(iv)

Direct that the Fleeing Driver Event: Investigation Practice Guide is attached to the Fleeing Driver

Policy.

5

48.

Endorse the recommendation

that all offences relating to fleeing drivers are assigned a case

category of 2 - Critical.

_________________________________

Glenn Dunbier

Deputy Commissioner: District Operations

1982 to Ti Lamusse

Police under the OIA

by New Zealand

Released

6

APPENDIX A

FLEEING DRIVERS: INVESTIGATION PRACTICE GUIDE

Fleeing Driver Policy

1.

The overarching principle of the Fleeing Driver Policy is that public, vehicle occupants(s) and

Police employee safety takes precedence over the immediate apprehension of a fleeing driver.

2.

One of the key principles is that an investigation is preferred over the commencement or

continuation of a pursuit wherever possible.

Definition

3.

A fleeing driver is any driver who has been signalled to stop by a constable, but fails to stop or

remain stopped, or a driver who flees as a result of Police presence, whether signalled to stop or

not.

1982 to Ti Lamusse

4.

A fleeing driver event has occurred as soon as a driver signalled to stop fails to do so, regardless

of whether the officer decides to initiate a pursuit with that driver.

Police Powers to Stop Vehicles

5.

The powers Police rely on to stop a vehicle are found in the following legislation:

a. Land Transport Act 1998, Section 114. The offence and penalty for failing to stop for an

enforcement officer is detailed in the Land Transport Act 1998, Section 52A.

b. Search and Surveil ance Act 2012 Section 9 and Section 121. The offence and penalty

relating to stopping vehicles is detailed in the Search and Surveil ance Act 2012, Section

177.

c. Prohibition of Gang Insignia in Government Premises Act 2013

Police under the OIA , Section 8 outlines the

powers, offence and penalty to stop a vehicle to exercise powers of arrest or seizure.

d. The COVID-19 Public Health Response Act 2020, Section 22. The offence and penalty

relating to the exercise of enforcement powers is detailed in Section 27 of the Act.

Holding Fleeing Drivers to Account 6.

If the driver of the fleeing vehicle is apprehended at the time of the event, the file is to be managed

in the normal manner by the initiating Police unit, with appropriate action taken against the driver

and/or passengers.

by New Zealand

7.

Where there is a mandatory period of disqualification, a prosecution is likely to be the most

appropriate course of action, however this does not preclude consideration of alternative

supported resolutions (e.g. a referral to Te Pae Oranga).

8.

If a pursuit is either a) not initiated, or b) abandoned, an investigation must be undertaken to

identify the driver and hold them to account.

Released

Creating the Fleeing Driver Investigation File 9.

Every fleeing driver event reported to the Police Emergency Centre must be resulted with either

a K6 (reported) or a K9 (arrest).

7

24. A search of the Police Infringement Bureau (PIB) database may provide avenues for enquiry if

an infringement notice has previously been issued to a driver of that vehicle. Email PIB Intel at

[email address]

25. If the vehicle has not been stolen, make enquiries at the address of the registered person as

soon as practicable to establish who is in possession of, or likely to be driving the vehicle. s.6(c)

26. Section 118(4) of the Land Transport Act 1998 requires the owner or hirer of the vehicle to provide

all information in their possession or obtainable by them, which may lead to the identification and

apprehension of the driver. The owner or hirer must provide this information

immediately.

27. If the registered person is based in a dif erent geographical area of New Zealand, initiate a 4Q

event through the Police Emergency Centre. The requirement is to speak with the owner or hirer

of the vehicle and obtain all information which may lead to the identification and apprehension of

the driver.

28. If initial enquiries to locate and speak with the registered person are unsuccessful, a NIA part file

is to be created and submitted to a supervisor for forwarding to the appropriate District to action.

1982 to Ti Lamusse

29. Complete a Formal Writ en Statement (FWS) and attach to the NIA file.

Details of Driver Supplied to Police 30. Where details of driver have been supplied to Police, but the driver is stil required to be located,

consider digital signage or a FLINT if there is potential risk to the public or Police.

31. Link the driver to the NIA file.

32. Enter either a ‘Sought’ or ‘WTI’ alert in NIA, with the text:

Required to be arrested / interviewed

in relation to a fleeing driver event at [time] on [date] in [place].

33. Provide direction in the NIA entry about how the information is to be submitted to the Of icer in

Charge of the file.

Police under the OIA

34. Update the NIA narrative detailing action taken.

Details of Driver Not Supplied to Police on Request

35. Where the details of driver are not supplied to Police on request, create a prosecution file

(summons) for ‘failing to supply information as to the identity of the driver’, as required under

Section 118 of the Land Transport Act 1998.

36. Serve the summons on the person who failed to provide the details to Police. Endorse the service

of the summons prior to submit ing the file.

by New Zealand

37. Attach all relevant documentation to the NIA file at case level.

38. Update the NIA narrative detailing action taken.

39. Consideration ought to be given to seeking discretionary disqualification under Section 80 of the

Land Transport 1998 for the offence of ‘failing to supply information as to the identity of the driver’

Released

on the basis that the vehicle was involved in a road safety offence.

40. Prepare the file for prosecution.

Vehicle Located in a Public Place – No Person(s) Present

9

41. The vehicle can be seized and impounded pursuant to the Section 123(1)(b) of the Land

Transport Act 1998 if the driver of the vehicle failed to stop (or remained stopped) as signalled,

requested or required under Section 114, Land Transport Act 1998

42. There is provision to impound the vehicle for 28 days under Section 96(1AB), Land Transport Act

1998 if an enforcement officer believes on reasonable grounds that a driver of the vehicle failed

to stop (or remained stopped) as signalled, requested or required under Section 114, Land

Transport Act 1998.

43. There is provision to impound the vehicle under Section 122(1) of the Search and Surveil ance

Act 2012, which allows an enforcement officer to move a vehicle to another place if they ‘find’ or

‘stop’ the vehicle, and have lawful authority to search the vehicle but it is impracticable to do so

at that place.

44. Section 122(2), Search and Surveil ance Act 2012 also allows an enforcement officer who has

the power to arrest a person, to move a vehicle to another place if they find or stop the vehicle,

and have reasonable grounds to believe it is necessary to move the vehicle for safekeeping.

45. Arrange for the vehicle to be towed to the appropriate local storage provider.

1982 to Ti Lamusse

46. Enter an ‘Impound’ alert against the vehicle in NIA as this wil assist with vehicle movements and

chain of custody.

47. Depending on the nature of the fleeing driver event, a search of the vehicle contents should be

considered as best practice. Refer to Appendix B. This Legal Memorandum sets out the legal

obligations to consider when searching impounded vehicles.

48. Al property seized by Police should be recorded in ‘PROP’ and the owner (if identified) provided

with an inventory receipt within 7 days.

49. A forensic examination of the vehicle should be considered as best practice to identify the driver

and/or vehicle occupants, as outlined in Section 123(1)(b) of the Land Transport Act 1998.

Police under the OIA

50. Request that Police Communications create a 4F event (Fingerprinting).

51. Notify the local SOCO. Advise them of the location of the vehicle and NIA file number relating to

the fleeing driver event.

NOTE: To subsequently review the results of the SOCO examination, the forensic case notes

made by the SOCO examiner wil be attached under the Forensic Node in the NIA file. These

notes wil state whether the identity of any person was identified during the examination.

52. Ensure all identified person(s) are linked to the NIA file.

by New Zealand

53. Complete follow up enquiries in relation to person(s) identified as a result of the forensic

examination to determine their relationship with the vehicle and/or people.

54. s.6(c)

55. Conduct an interview based on the Best Practice Interviewing Suspects Guidelines.

Released

56. Where the evidential sufficiency and public interest tests detailed in the Solicitor General’s

Prosecution Guidelines are met, charge the person with the initial offence identified, failing to

stop and any associated offending.

10

57. Create the appropriate summons / arrest / youth aid / alternative resolution file and submit for

supervisor endorsement and direction.

58. Attach all relevant documentation to the NIA file at case level.

59. If the person(s) identified in the forensic examination lives in a dif erent geographical area of New

Zealand, create a NIA part file and submit to a supervisor for forwarding to the appropriate District

to locate and interview.

60. If the registered person refuses to provide information to Police as required under Section 118(4)

of the Land Transport Act 1998, refer to the ‘Details of Driver not supplied to Police’ section of

this document.

61. Where the fleeing driver is identified, but is still required to be located, consider digital signage

or a FLINT if there is potential risk to the public or Police.

62. Enter either a ‘Sought’ or ‘WTI’ alert in NIA, with the text:

Required to be arrested / interviewed

in relation to a fleeing driver event at [time] on [date] in [place].

63. Provide direction in the NIA entry about how the information is to be submitted to the Of icer in

1982 to Ti Lamusse

Charge of the file.

64. If Police establish the vehicle was used in a fleeing driver event and the vehicle is not registered

in the name of the current owner, or with the current address of that person, a non-operation

order may be affixed under Section 248 of the Land Transport Act 1998. This prohibits the vehicle

from being driven on a road until such time as it has been registered in the name and current

address of the owner.

65. Update the NIA narrative detailing action taken

Vehicle Located on Private Property 66. If the general provisions of entry onto private property under Section 119 of the Land Transport

Act 1998, or under Section 120 of the Search and Surveil ance Act 2012 do not apply (i.e. fresh

Police under the OIA

pursuit, loss/destruction evidence, used in further offending, or impractical), obtain a search

warrant to enter, seize and impound the vehicle as per Section 119(5) of the Land Transport

Act 1998.

67. Attach an electronic copy of the Search Warrant Application and the Warrant to the NIA file at

case level.

68. Interview the vehicle owner(s) and/or occupants of the address to determine who had

possession of the vehicle on the ‘applicable day’.

69. Arrange for the vehicle to be towed to the appropriate local storage provider as per the

by New Zealand

conditions sought in the Search Warrant.

70 Enter an ‘Impound’ alert against the vehicle in NIA as this wil assist with vehicle movements and

chain of custody.

71. A forensic examination of the vehicle should be considered as best practice to identify the driver

and/or

Released vehicle occupants, as outlined in Section 123(1)(b) of the Land Transport Act 1998.

72. Request that Police Emergency Centres create a 4F event (Fingerprinting).

73. Notify the local SOCO. Advised them of the location of the vehicle and NIA file number relating

to the fleeing driver event.

11

NOTE: To subsequently review the results of the SOCO examination, the forensic case notes

made by the SOCO examiner wil be attached under the Forensic Node in the NIA file. These

notes wil state whether the identity of any person was identified during the examination.

74. Ensure all identified person(s) are linked to the NIA file.

75. Complete follow up enquiries in relation to person(s) identified as a result of the forensic

examination to determine their relationship with the vehicle and/or people.

76. s.6(c)

77. Conduct an interview based on the Best Practice Interviewing Suspects Guidelines.

78. Where the evidential sufficiency and public interest tests detailed in the Solicitor General’s

Prosecution Guidelines are met, charge the person with the initial offence identified, failing to

stop and any associated offending.

79. Create the appropriate summons / arrest / youth aid / alternative resolution file and submit for

supervisor endorsement and direction.

1982 to Ti Lamusse

80. Attach all relevant documentation to the NIA file at case level

81. If the person(s) identified in the forensic examination lives in a dif erent geographical area of New

Zealand, create a NIA part file and submit to a supervisor for forwarding to the appropriate District

to locate and interview.

82. If the registered person refuses to provide information to Police as required under Section 118(4)

of the Land Transport Act 1998, refer to the ‘Details of Driver not supplied to Police’ section of

this document.

83. Where the fleeing driver is identified, but is still required to be located, consider digital signage

or a FLINT if there is potential risk o the public or Police.

Police under the OIA

84. Enter either a ‘Sought’ or ‘WTI’ alert in NIA, with the text:

Required to be arrested / interviewed

in relation to a fleeing driver event at [time] on [date] in [place].

85. Provide direction in the NIA entry about how the information is to be submitted to the Of icer in

Charge of the file.

86. If Police establish the vehicle was used in a fleeing driver event and the offender is not the

registered owner, a non-operation order may be affixed under Section 248 of the Land Transport

Act 1998 This prohibits the vehicle from being driven on a road until such time as it has been

registered in the name and current address of the owner.

87. Update the NIA narrative detailing ac

by New Zealand tion taken.

District Review and Monitoring 88. The file holder’s immediate supervisor is responsible for monitoring and reviewing the timeliness

and quality of the fleeing driver investigation in NIA.

89. Each D

Released istrict wil nominate a person who is responsible for auditing and monitoring all fleeing

driver investigation files. In many cases this wil be the person responsible for reviewing the

District’s Fleeing Driver Notifications.

12

90. District oversight wil ensure that fleeing driver investigations are progressed in a timely manner,

meet a consistently high standard of investigation and effectively mitigate the risk fleeing drivers

pose to our communities by identifying and holding offending drivers to account.

91. As part of the audit and review process, the District reviewer wil ensure that:

a. There is a corresponding NIA investigation file for every fleeing driver notification.

b. On completion of the District Review, the Fleeing Driver Notification form is printed as a

PDF document and attached to the NIA file.

c. The correct offence code has been used to assist with the national audit process.

d. Investigations are of a high standard and follow the Fleeing Driver Investigation Practice

Guide.

e. Feedback is provided to the supervisor to acknowledge good practice, and to address

any identified areas for improvement.

1982 to Ti Lamusse

Police under the OIA

by New Zealand

Released

13

APPENDIX A

Legal Memorandum relating to General Principles of Search and Inventory

1.

Police are entitled to search a vehicle they have impounded in order to make an inventory

of personal property for the benefit of the owners of the vehicle or owners of the property.

Police are entitled to search the vehicle without warrant provided they do so reasonably

and for the purpose of preserving property and identifying its owner. Searches of this

nature conducted reasonably and for these purposes, will not breach Section 21 of the

NZ Bil of Rights Act.

2.

Police have a discretionary common law duty to take possession of items of property in

circumstances where an owner is unable to take steps to secure the safety of that

property.

3.

Where there is no immediate or imminent danger to the impounded vehicle and there is

a high possibility that the property in the vehicle would be stolen, lost or damaged if left

unprotected, the public have a legitimate expectation that Police wil secure and care for

that property.

1982 to Ti Lamusse

4.

When Police take action to protect or preserve property but not in connection with any actual

or anticipated criminal offending, Police becomes a bailee and is under a legal obligation to

keep the property safe and if possible, return the property to the owner. The legal obligation

arises from the decision to take responsibility for the property, regardless of whether the

owner's identity is known or not.

5.

If it is necessary to conduct a search of the property to ascertain its ownership and/or its

nature, that search must not be done unreasonably. An excessive search or one conducted

for an ulterior purpose, for example to obtain evidence of criminal offending, would not be

reasonable and indeed may be unlawful. But if a police officer is genuinely acting for the

predominant purpose of preservation of property, the fact that he or she may suspect wrong-

doing associated with the property wil not, in itself, make the dealing with the property either

unlawful or unreasonable at common law or under Section 21 of the New Zealand Bil of Rights

Act.

Police under the OIA

a. If an occupant of an impounded vehicle denies ownership or knowledge of property

located in the vehicle, Police can legitimately inspect the contents in order to

ascertain the description of the property and the identity of its owner.

b. If, in the course of examining property in an impounded vehicle, an officer finds

evidence of criminal offending, any relevant power to search without warrant under

the Search and Surveil ance Act should immediately be engaged so that that

evidence can be examined and seized lawful y.

by New Zealand

Released

14

Feedback received

Reference

OCGG/20/32

Title

Fleeing driver events: Investigation Practice Guide

Date paper sent for

Wednesday 23 September 2020

1982 to Ti Lamusse

consultation

In the table below, please record the names of those people consulted, their feedback and your action or recommendations. Please clearly state if no response is received from any

parties. If consultation has not been undertaken, a full explanation must be provided on the Cover Sheet.

Key themes

Feedback provided

Action taken or recommended following the

feedback

Support for the paper Overall, feedback received was positive, with all submit ers expressing

support for the paper and the investigative process detailed.

• The practice outlined wil possibly have an impact on reducing

the number of fleeing driver events occurring in our District,

which result in D&SI as a result of the incident.

Police under the OIA

• The suggested best practise may positively affect the number of

District vehicles intentionally rammed or damaged as a result of

Fleeing Driver incidents.

• We support it as positive step forward.

• The document clearly identifies actions to be taken and avenues

for enquiry which should provide some consistency. It would be

good to see more emphasis on the follow up investigation as

these aren’t always completed as they should be. This may be

addressed in the proposed audi

by New Zealand t process.

15

Released

• The practice guide looks good. The intent of this paper and the

process described are very worthy and thorough. Any steps we

can take to reduce the risk posed by fleeing driver incidents are

worth the ef ort.

1982 to Ti Lamusse

• This is an extremely sound initiative and aligns with delivering

what the public expect and deserve – especially in reducing

harm to communities and groups where we need to increase

positive interactions e.g. Youths, Māori.

• This is great thank you, makes perfect sense.

• This has significant frontline safety benefits via giving us more

time to investigate fleeing drivers for potential threats before we

pursue.

• Fully supportive – the policy strikes me as being very

comprehensive too, and that’s great.

Police under the OIA

• We have identified poor investigation practice as a key failing in

identifying offenders, [so this wil support efforts] to improve our

overall performance.

Resource implications While supportive of the intent and objectives of the paper, some

A high percentage of fleeing driver events are

reservations were expressed about the resourcing required to carry out already resolved by way of investigation (30%),

fleeing driver investigations.

however any potential increase in resource

required is difficult to quantify.

• I would have thought that completing an investigation into a

fleeing driver event is a consider

by New Zealand ably longer and more resource- Arguably, an increased emphasis on resolving

intensive process than a pursuit?

fleeing driver events by way of investigation may

result in time and cost savings.

16

Released

Eastern

Eastern

Currently, when someone is injured or kil ed as a

It is resource intensive and wil require co-ordination across shifts, as

result of a pursuit, Police commit significant

many of these are night shifts and then they go onto days off. This

resources to the criminal investigation and any

makes it challenging to identify who would hold the file.

subsequent prosecution, the IPCA investigation,

the employment investigation, and the coronial

1982 to Ti Lamusse

There is work that ISU could potentially do but with everything this

inquiry, as well as the media response and

would mean a review of priorities

engagement with the victim’s family.

Counties Manukau

From a welfare perspective we also need to factor

in welfare officer time, leave and rehabilitation

1. The number of Fleeing Driver incidents within our District are

time if one of our people is physically or

considerable, and the subsequent investigation process as

psychologically injured as a result of the pursuit.

proposed would impact and capability.

The broader social cost per fatality is $4.56

2. In our current environment, frontline staff (who are predominantly million. For non-fatal injuries, the average social

the engaging unit) wil not have time outside of their BAU to give cost is estimated at $477,600 per serious injury

sufficient investigation action to these incidents. Bearing in mind and $25,500 per minor injury.3

that some units may be involved in several fleeing driver

incidents in one shift.

The comparison is a simple investigation and

Police under the OIA

prosecution file, versus criminal / IPCA /

3. Due to their inexperience, they would not be capable of

employment investigations, media headlines that

completing the entire investigation, which as suggested would

negatively impact trust and confidence in Police,

need Search Warrant applications being prepared, cell-phone

grieving family, friends, colleagues and an

warrants, and visits to various addresses to locate vehicle

avoidable death.

owners and possible driver suspects….whilst continuing their

frontline BAU They simply do not have the skil or experience,

In the national hui there was debate about who

nor the time in a frontline PST position.

should hold the investigation file. Some Districts

wanted these to go to their enquiry office, but not

all Districts have an enquiry office.

by New Zealand

3 https://www.transport.govt.nz/mot-resources/road-safety-resources/roadcrashstatistics/social-cost-of-road-crashes-and-injuries/

17

Released

4. Currently RP staff do follow up inquiries and Search warrants

The alternative view was that the investigation file

with ISR suspects, and this severely impacts on their BAU. If

should sit with the officers initiating the pursuit

they were to conduct investigations into the Fleeing Driver

except in exceptional circumstances (e.g. crash or

events they initiate, it would severely impact RP productivity.

fatal pursuit, which generally sit with CIB).

1982 to Ti Lamusse

5. Fleeing Drivers need to be held accountable, but we would need There was further discussion that the

a dedicated position/s to effectively investigate files for fleeing

investigation practice guide should not be

drivers.

prescriptive about the ‘how’, but rather allow each

District to determine how to allocate their

6. By having a single point, they can be easily monitored as

resources, dependant on structure and demand,

suggested in #89 for compliance to the process and good

to achieve the desired outcome.

investigation procedure. Increased knowledge of the process

would lead to more streamlined and effective investigations.

7. I would suggest 2 x FTE in ISU to undertake the investigation

process to hold the fleeing driver accountable, if the unit who

initiated the pursuit could not resolve it on the shift.

Police under the OIA

Consistent approach It was noted the paper was not specific about how fleeing driver events

Refer above.

to assigning files

would be assigned for investigation.

• What’s our expectation about how the matters are passed on to

investigation / enquiry units?

• A nationally consistent (at the very least a TM consistent)

approach to assigning these files for investigation [would be

useful].

by New Zealand

18

Released

For example, if a car registered to Orewa is pursued in Papakura

who should hold the investigation? And which workgroup wil

take on the investigations? These matters could be prescribed

at a national level to set clear expectations.

1982 to Ti Lamusse

Priority of

How to prioritise fleeing driver investigations against competing demand Paragraphs 36 – 39 added to include a

Investigations

was raised several times.

recommendation that all offence codes relating to

fleeing drivers be assigned a case category of

• I’d like to see the policy address the priority of these

‘Critical’.

investigations from a case management perspective.

• What priority wil be afforded to these [investigations] against

other demand?

Case Management

It was noted that robust case management wil be required to ensure

Paragraph 42 added.

files are resolved within appropriate timeframes.

A new reporting platform is being developed for

Feedback identified that national reporting would be useful to assist with Fleeing Driver Notifications. This is expected to

Police under the OIA

oversight and monitoring of investigations.

be operational by April 2021. There wil be

internal reporting built into the programme, and

• It would be helpful if a reporting tool (Business Objects or SAS)

SAS reporting will also be available.

could be built and sent out to Districts on a monthly basis to

assist with the auditing to ensure consistency and accountability. An interim solution wil be explored.

• Central District provided a potential solution for consideration.

The following suggestion was proposed to enhance the audit process:

• With the large number of PREC c

by New Zealand odes for actual offences

Work is underway with the Police Emergency

available, could we have a new incident code for any fleeing

Centres and Assurance Group, Strategy and

Service to identify the best solution.

19

Released

driver event? I would propose 6U (close to 1U but stil distinct),

Currently the code ‘PURS’ is used in CARD,

which is currently not in use.

which enables the transfer of event data from

CARD through to NIA.

Then any fleeing driver event, regardless of what the correct

1982 to Ti Lamusse

offence PREC code might be, could be entered 6U into CARD

A fleeing driver event is not able to be recoded by

by Comms, which would streamline the data retrieval/review

officers via mobility, however these events can be

process.

recoded by the Police Emergency Centres on

request. For example, where an elderly driver is

A failsafe could be included whereby a 6U could not be recoded not aware of the Police signal to stop, or in the

or K1d without supervisor approval (much the same as 5Fs

event of a visiting driver, who did not understand

currently). With the opportunity to conduct this review on

the correct action to take when signalled to stop.

procedure and with the high risk fleeing driver ncidents pose, as

well as to promote and allow for a robust auditing process, I

would think a mandatory supervisor approval for recode is

appropriate and would also look good from an external scrutiny

(i.e. IPCA) point of view.

Language and format Policy Group provided recommendations for rewording to enhance

Recommendations incorporated as appropriate.

Police under the OIA

clarity.

The Police Instructions team identified the term ‘good practice’ is

Paper amended to Fleeing Drivers: Investigation

preferable to ‘best practice’.

Practice Guide and all references updated.

The Police Instructions team also identified significant repetition that

occurs under different fleeing driver results / situations.

• The policy could be significantly reduced in content if [we could]

The working group discussed the issue of

process map and convert to tables. This would deliver enhanced repetition, but felt it was helpful for people to be

readability to users and when added to the Fleeing Driver policy able to follow through the process for a given

by New Zealand

wil have consistent style and language.

situation i.e. vehicle located public place.

20

Released

Once the Fleeing Driver: Investigation Practice

Guide has been approved, we will work with the

Police Instructions team to integrate the content

into the Fleeing Driver Policy in a way that

ensures consistency and maximises readability.

1982 to Ti Lamusse

Alternative

A question was raised around whether an additional recommendation

If an offence carries a penalty of mandatory

Resolutions

be made that this change is specifically considered as part of Te Pae

disqualification, then only the Courts have

Oranga/Community panels, to see if changes can be made to

jurisdiction.

accommodate.

Contravention of section 114 of the Land

Transport Act 1998 (i.e. failing to stop or remain

stopped when signalled to do so) carries a

mandatory period of disqualification.

However, paragraph 7 of the Fleeing Driver:

Investigation Guide refers to alternative

resolutions. Te Pae Oranga has been added as a

specific example for consideration.

Police under the OIA

Legislative Change

Feedback received from one District was that legislative change would

Forwarded to the Policy and Partnerships team

assist with the investigation process, enabling a greater number of

for assessment and follow up. Response below.

offending drivers to be identified.

Registration to ‘persons unknown’

• It is currently the purchaser’s responsibility to change ownership

This is an interesting proposal. We’l get this

of the vehicle As a result, a significant number of vehicles on

logged on the issues register for further work

the road are registered to ‘

persons unknown’. This is regularly

given it clearly relates to supporting investigations

seen when dealing with impounded vehicles. This wil

into fleeing drivers and our shifting preference

automatically result in the investigation being halted. Therefore,

towards this, rather than pursuit.

I believe legislative change needs to occur to place the onus on

by New Zealand

the vehicle seller to ensure correct ownership of the vehicle is

Other options being explored in terms of

recorded.

legislative change include:

21

Released

Comment was made that the judiciary regularly ‘convict and discharge’

- Minimum sentencing option (penalty) for

defendants for failing to stop matters.

failing to stop

• Until there is a decent penalty in place, there is no accountability.

- Minimum non-concurrently served

1982 to Ti Lamusse

There is not even any point in following up with a prosecution,

imprisonment for intentionally driving at an

but we do.

enforcement officer or emergency worker,

including the ramming of a police car

It was also noted that if the owner or driver fails to provide details it’s a

fine only penalty through the courts.

- Vehicle seizure for vehicle owners who fail

to identify driver details of a vehicle that

• It would be a benefit is a change could be made to the penalty

has failed to stop

for a breach of 118(4).

- A change to the penalty for a breach of

118(4)

Police under the OIA

by New Zealand

22

Released