1.2.

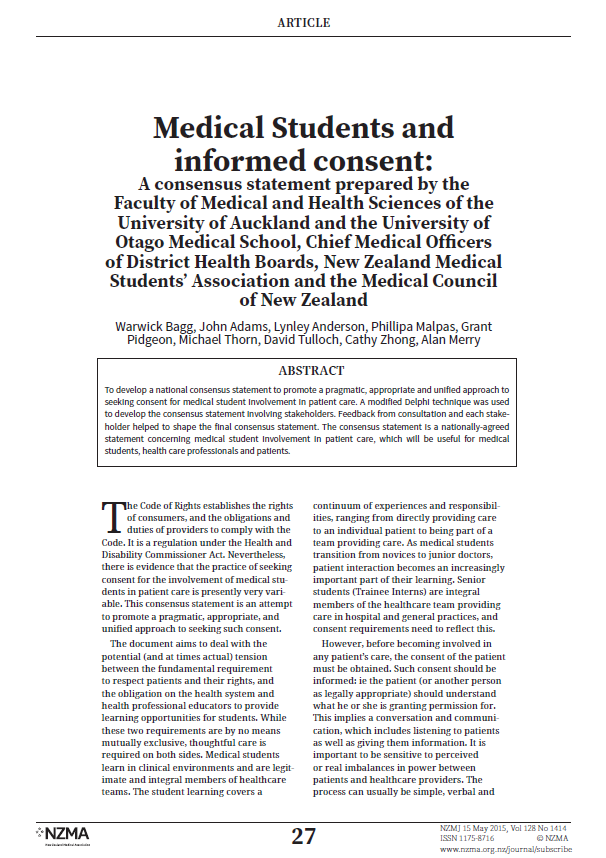

Medical Students and informed consent

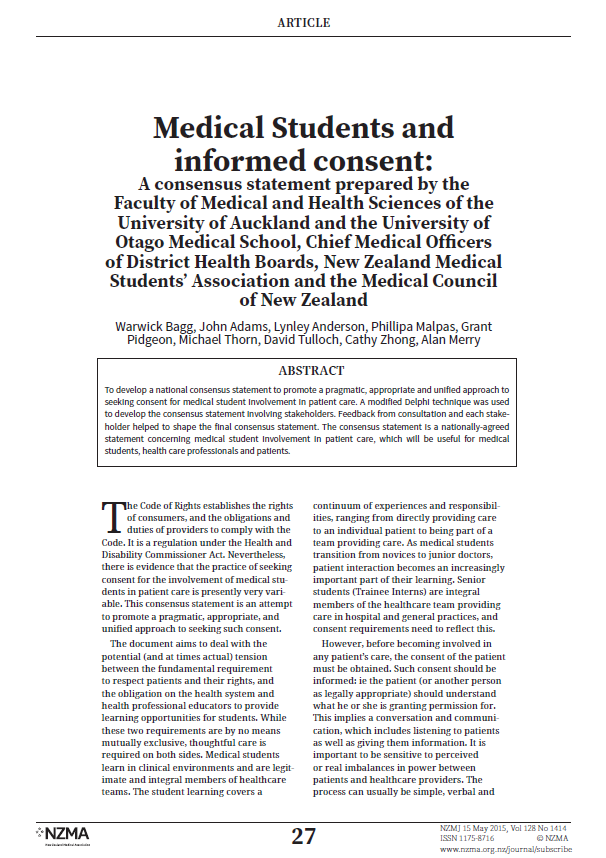

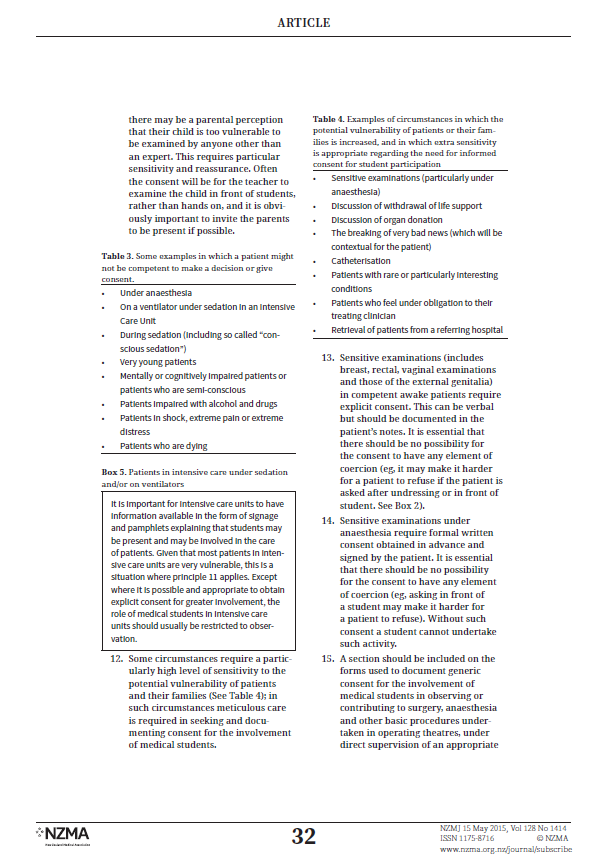

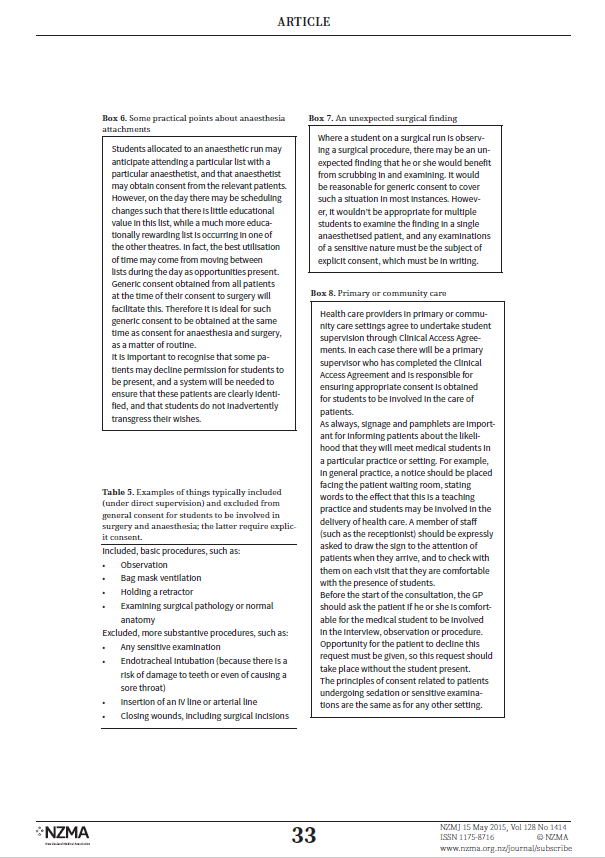

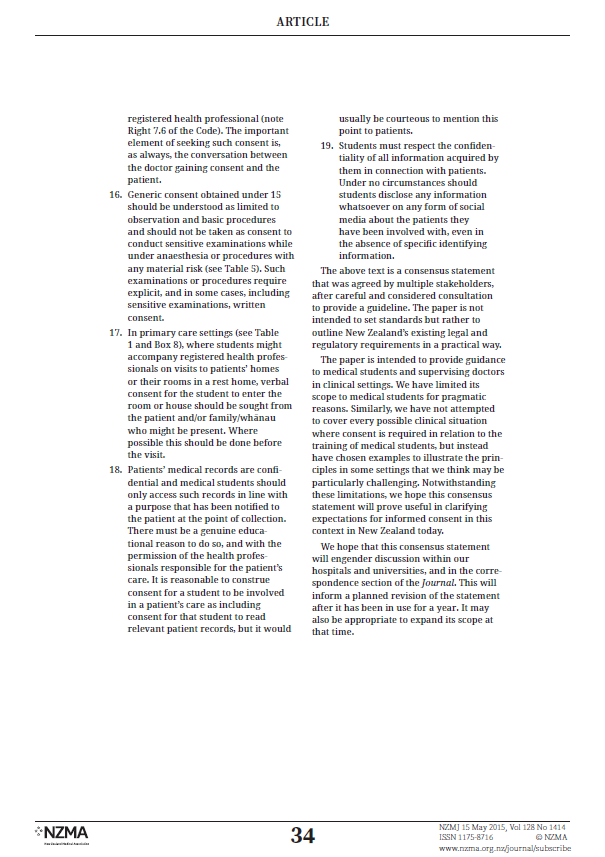

A national consensus statement was developed to promote a pragmatic, appropriate and

unified approach to seeking consent for medical student involvement in patient care. Please

review article below:

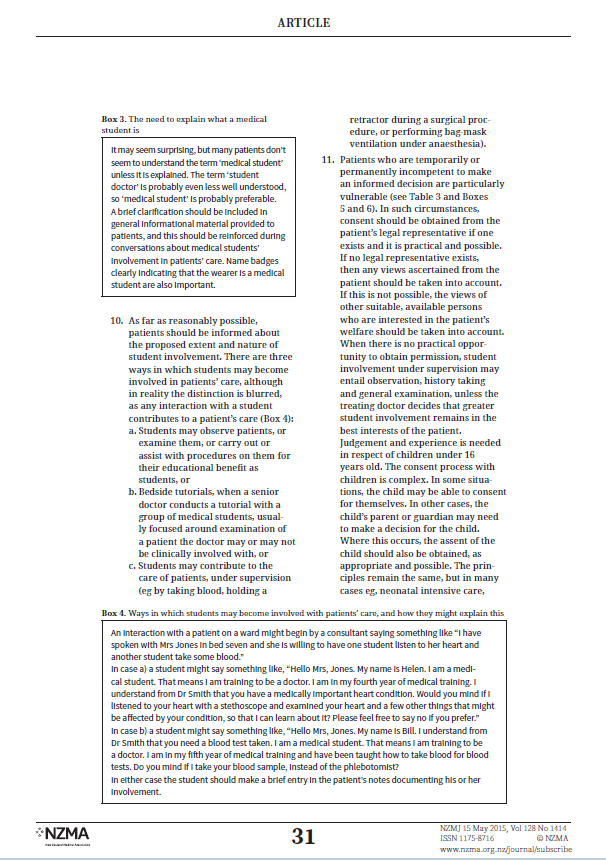

2

3

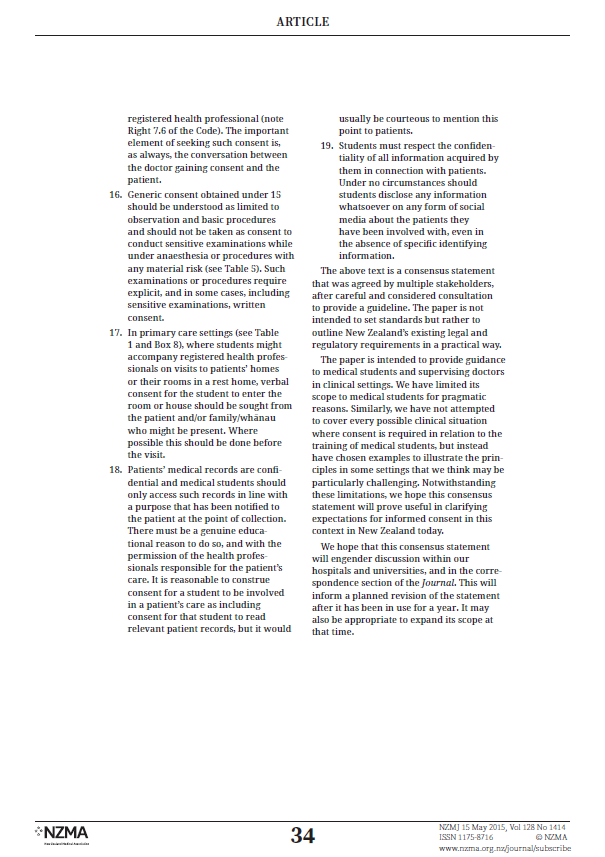

Last updated 30.10.2017

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

Excerpts from the Code of Ethics of the New Zealand Medical Association (NZMA)

Code of ethics

All medical practitioners, including those who may not be engaged directly in clinical

practise, will acknowledge and accept the following Principles of Ethical Behaviour:

1. Consider the health and well-being of the patient to be your first priority.

2. Respect the rights, autonomy and freedom of choice of the patient.

3. Avoid exploiting the patient in any manner.

4. Practise the science and art of medicine to the best of your ability with moral

integrity, compassion and respect for human dignity.

5. Protect the patient’s private information throughout his/her lifetime and following

death, unless there are overriding considerations in terms of public interest or

patient safety.

6. Strive to improve your knowledge and skills so that the best possible advice and

treatment can be offered to the patient.

7. Adhere to the scientific basis for medical practise while acknowledging the limits of

current knowledge.

8. Honour the profession, including its traditions, values, and its principles, in the ways

that best serve the interests of the patient.

9. Recognise your own limitations and the special skills of others in the diagnosis,

prevention and treatment of disease.

10. Accept a responsibility to assist in the protection and improvement of the health of

the community.

11. Accept a responsibility to advocate for adequate resourcing of medical services and

assist in maximising equitable access to them across the community.

12. Accept a responsibility for maintaining the standards of the profession.

Guide to the ethical behaviour of physicians

The profession of medicine has a duty to safeguard the health of the people and minimise the

ravages of disease. Its knowledge and conscience must be directed to these ends. Ethical

codes have developed to guide the members of the profession in achieving them. The

Hippocratic Oath was an initial expression of such a code. More recent codes have developed

from this and from a consideration of modern ethical dilemmas and these are embodied in a

number of important declarations, international codes and statements from the World Medical

Association. These include:

1. The Declaration of Geneva (1948, amended in 1968, 1983, 1994, 2005, 2009)

2. The World Medical Association International Code of Medical Ethics (1949, 1968 and

1983, 2004)

3. The following statements by the World Medical Association which deal with particular

issues:

- The Declaration of Helsinki dealing with biomedical research (1964, 1975 and 1983,

1989, 1996, 2000, 2002, 2004, 2008).

12

Last updated 30.10.2017

- The Declaration of Oslo on therapeutic abortion (1970, 1983, 2006).

- The Declaration of Tokyo on a doctor’s responsibility towards prisoners (1975, 2005,

2006).

- The Declaration of Lisbon on patient’s rights (1981, 1995, 2005).

- The Declaration of Venice which deals with terminal illness (1983, 2006).

- The Declaration of Ottawa on child health (1998, 2009).

- The Declaration of Washington on patient safety (2002).

- The Declaration of Madrid on euthanasia (1987, 2005).

- The Declaration of Delhi on health and climate change (2009)

For latest updates and new Declarations, regularly check the website of the World Medical

Association,

www.wma.net

These have been endorsed by each member organisation, including the New Zealand Medical

Association, as general guides having worldwide application.

The New Zealand Medical Association accepts the responsibility of delineating the

standard of ethical behaviour expected of New Zealand Medical Practitioners.

An interpretation of these principles is developed in the following pages, as a guide for

individual doctors.

Responsibilities to the patient

1. Standard of care

Practise the science and art of medicine to the best of one’s ability in full technical

and moral independence and with compassion and respect for human dignity.

2. Continue self-education to improve one’s personal standards of medical care.

3. Ensure that every patient receives a complete and thorough examination into their

complaint or condition

4. Ensure that accurate records of fact are kept

5. Respect for patient

Ensure that all conduct in the practise of the profession is above reproach, and

that neither physical, emotional nor financial advantage is taken of any patient.

6. Patient’s right

Recognise a responsibility to render medical service to any person regardless of

colour, religion, political belief, and regardless of the nature of the illness so long

as it lies within the limits of expertise as a practitioner.

7. Accepts the right of all patients to know the nature of any illness from which they are

known to suffer, its probable cause, and the available treatments together with their

likely benefits and risks.

8. Allow all patients the right to choose their doctors freely.

9. Recognise one’s professional limitations and, when indicated, recommend to the

patient that additional opinions and services be obtained.

10. Keep in confidence information derived from a patient, or from a colleague regarding

a patient, and divulge it only with the permission of the patient except when the law

13

Last updated 08.11.2017

requires otherwise.

11. Recommend only those diagnostic procedures which seem necessary to assist in the

care of the patient and only that therapy which seems necessary for the well-being of

the patient. Exchange such information with patients as is necessary for them to

make informed choices where alternatives exist.

12. When requested, assist any patient by supplying the information required to enable

the patient to receive any benefits to which he or she may be entitled.

13. Render all assistance possible to any patient where an urgent need for medical care

exists.

Continuity of care

Ensure that medical care is available to one’s patients when one is personally absent. When

professional responsibility for an acutely ill patient has been accepted, continue to provide

services until they are no longer required, or until the services of another suitable physician

have been obtained.

Personal morality

When a personal moral judgement or religious conscience alone prevents the recommendation

of some form of therapy, the patient must be so acquainted and an opportunity afforded the

patient to seek alternative care.

14

Last updated 08.11.2017