Dear New Zealand Police,

I would like to request copies of these 14 Police Manual chapters:

1) Covert Human intelligence source

2) Intel - Collection management

3) Intel - Decision-making and planning

4) Intel - Deconfliction

5) Intel - Evaluating effectiveness of intel

6) Intel - Intelligence categories

7) Intel - Intelligence for investigations

8) Intel - Intelligence policing methods

9) Intel - Intel igence products

10) Intel - Introduction to intel igence

11) Intel - Issue motivated and protest groups' intel igence

12) Intel - Legal opinion

13) Intel - Selection of operation names

14) Intel - The intelligence cycle

Yours faithfully,

Sebastian

The Intelligence cycle

Table of Contents

Table of Contents

2

Summary

4

What s the New Zea and Po ce Inte gence Cyc e?

4

D agram

4

Direction

6

How does d rect on occur?

6

Scann ng

6

P ann ng

6

Repor ng cyc es

6

Genera ask ng

7

Terms of Reference

7

Collection

8

P anned, focused and coord nated co ect on

8

How does nformat on enter Po ce?

8

Tasked co ect on

8

Open-source nformat on

9

Evaluation

11

Adm ra ty Grad ng System

11

Examp es

11

Collation

12

Analysis

13

What s ana ys s?

13

Types of ana ys s

13

Inference Deve opment Mode

15

Responses

17

What are responses?

17

Purpose of responses

17

Dissemination

18

What s d ssem nat on?

18

Four standard product types

18

L nk ng products and dec s on-mak ng

19

Know who he key dec s on makers are and how o nf uence hem

19

Dec s on makers are rare y n e gence profess ona s

19

P ck he r gh presen a on s y e and forma

19

Dec s on makers are faced w h mu p e compe ng demands

20

Know wha s mpor an

20

Seek c ar y on wha dec s on makers expec

20

Focus on peop e and con ex

21

Key dec s on makers may be ou s de he mmed a e po c ng env ronmen

21

Be aware of he cons ra n s on dec s on mak ng

21

Review

22

Feedback

22

Components of good products

22

Products w be better nformed by nvo v ng others

23

We wr tten products do not confuse facts and op n ons

23

Good ana ys s needs to add rea va ue

23

T me ness s a ways a factor

23

Execut ve summar es are key to focus ng attent on

23

Good products get to the po nt

23

Exper ence for Po ce off cers s ma n y about ev dence

23

Good aw enforcement ana ys s

24

Products must comp y w th po cy, procedure and eg s at on

24

The Inte gence cyc e

Summary

This section contains the following topics:

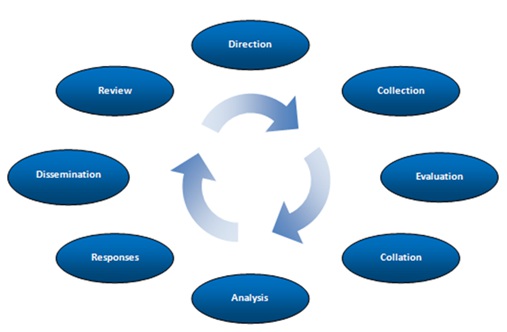

What is the New Zealand Police Intelligence Cycle?

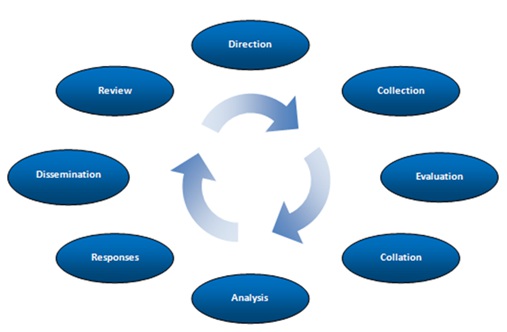

Diagram

What is the New Zealand Police Intelligence Cycle?

The Intelligence Cycle sets out a model for how information is processed into intelligence in order to inform decision

making and drive action. It is essentially a business model for intelligence. The cycle is a continuous, iterative process.

Every new piece of data or information can be evaluated and incorporated into an ongoing interpretation of crime and

crash environments, and turned into actionable intelligence.

Raw information gathered through the collection process is not intelligence. Rather, intelligence is the knowledge derived

from the logical integration and interpretation of that information, which renders it sufficiently robust to enable Police to

draw conclusions related to a particular victim, crime, criminal, road trauma or event.

In reality, the cycle is not simply a linear, sequential process. Intelligence staff will often be simultaneously collecting,

collating and analysing information streams against multiple problems, and with direction occurring and being refined at

various stages. In this respect it is iterative and does not simply take one cyclic revolution and conclude. An analyst may

seek direction, collect, collate, analyse, review, seek further direction, collect and collate several times over before

reaching robust analytical conclusions and recommendations. Similarly, the cycle may be adapted or abbreviated by

experienced practitioners where timeframes are short or other pressures are at play.

Despite this, the Intelligence Cycle is the most elementary mechanism depicting how intelligence staff apply a process to

transforming information into intelligence.

Diagram

The Intelligence Cycle was developed specifically for the New Zealand Police by a working group of intelligence specialists

supporting the National Intelligence Office in 2008. It revised and refined a nine stage model designed by the Policing

Development Group in 2004. It consists of these eight parts:

Direction

Collection

Evaluation

Collation

Analysis

Responses

Dissemination

Review

4/24

The Inte gence cyc e

5/24

The Inte gence cyc e

Direction

This section contains the following topics:

How does direction occur?

Scanning

Planning

Reporting cycles

General tasking

Terms of Reference

Direction is the initiating stage of the Intelligence Cycle. Effective direction ensures that intelligence effort is appropriately

prioritised and aligned to organisational strategies and objectives. Direction may be internal from within the intelligence

unit or external from the Executive or other parts of the organisation. Occasionally direction may be driven from the

bottom up by individual intelligence staff. Similarly, direction in its broadest sense could be received from other

Government agencies or ad hoc organisations.

Direction should be clear and managed through a central point (either the National Intelligence Centre or respective

District Intelligence management).

How does direction occur?

Direction can be generated in four general ways including:

Scanning

Planning

Reporting cycles

General tasking

Scanning

Scanning is a constant process whereby ongoing (i.e. not specifically targeted) data collected by Police and partner

agencies is used to:

identify recurring problems or issues of concern to the community and Police

select problems or issues for closer examination

identify the consequences of the problem for the community and Police

enable intelligence led prioritisation of problems

develop broad goals for the responses which will be developed later on within the intelligence cycle

confirm that the problems/issues exist, and to the extent that they may be reported on

determine the frequency of the problem and how long it has been occurring.

Planning

Planning what product is required, for whom, and then how data will subsequently be collected is crucial to the

intelligence process. Effective planning assesses existing data and ensures that additional data collected will fill any gaps

in current information holdings. Intelligence planning and subsequent collection are a joint effort that requires a close

working relationship between analysts, who understand how to manage, compile, and analyse information, and collection

managers, field intelligence officers, and other specified staff.

Planning requires that Intelligence staff, often in direct consultation with decision makers, identify the outcomes they

want to achieve from their collection efforts. This identification directs the scope of the analyst's effort, for example an

analysis to identify youth gangs in Counties Manukau, or a more complex inquiry to determine the likelihood that criminal

extremists or terrorists will attack facilities during a major international event hosted in New Zealand. Collection planning

and Collection are specifically covered in the next section.

Reporting cycles

6/24

The Inte gence cyc e

Police reporting cycles for intelligence are triggered by core products and processes designed to provide direction and

tasking.

Strategic

Produced every two year and linked to the development of district and service centre business

assessments

plans.

Tactical assessments Produced quarterly by districts to inform the Tasking & Coordination process.

The reporting cycle is logically linked in to scanning and planning.

The Deployment model and the advent of District Command Centres is driving changes to tasking and reporting

mechanisms for Intelligence. These have to result in the development of standardised operating procedures or national

best practice.

General tasking

Intelligence products are generally client solicited. Simply stated, the intelligence group is tasked by the client to generate

a product. The analyst's task is to find answers and seek insights relating to a defined problem by applying the intelligence

process. Examples of product types resulting from general taskings could include:

problem profiles

subject profiles

knowledge products

FLINT Products.

Effective application of intelligence processes is reliant on clear direction, problem articulation and prioritisation from

decision makers.

Terms of Reference

Terms of Reference (ToR) are the outcome of the Direction stage of the Intelligence Cycle. The ToR effectively forms an

agreement of what the client requires and what the analyst/intelligence staff can or will provide. It should define the

problem (as far as this is possible in the early stages of a product or project), and outline the agreed aim, objectives and

scope of the product. The Terms of Reference should be finalised through a process of communication and negotiation

either directly between the client and the analyst (or the Intelligence manager). A ToR template is available on the

Intelligence Community Sharepoint.

7/24

The Inte gence cyc e

Collection

This section contains the following topics:

Planned, focused and coordinated collection

How does information enter Police?

Tasked collection

Open source information

Collection is the directed, focussed gathering of information to meet intelligence requirements.

The New Zealand Police Intelligence Collection Framework (November 2013) clearly articulates collection principles and

processes for Collection. It is the prime reference for all matters of intelligence collection and collection planning.

Planned, focused and coordinated collection

To be effective, intelligence collection must be planned, focused and coordinated. Intelligence is reliant on access to

information from an array of sources and agencies (SANDA) including information held in Police databases such as NIA,

Investigation Management Tools, CARD and mapping applications. This information enables Police to produce a

comprehensive picture of the crime and road trauma environments and to determine its priorities. The application of

information management policies and procedures ensures that the appropriate information is recorded and developed as

intelligence, and that this intelligence is maintained and accessible to assist decision making through the tasking and

coordination process.

In order to effectively focus collection there must be very clear guidance at every level about what needs to be collected.

This is usually gained by the analyst understanding what product they are required to produce or more generally, what

questions they are required to answer. By process of understanding what information is already held or available,

information gaps can be determined and understood. These are sometimes referred to as 'known unknowns.'

Once information gaps are understood, intelligence staff need to plan and assign the most appropriate collection asset to

address the particular requirement. This means that analysts and collection managers must understand the capabilities,

limitations and strengths of each SANDA. This understanding also includes the legal powers used to request information,

how long it takes SANDA to collect and deliver information, limitations such as security (including information security),

how long it takes to task them / request them, how SANDA can be affected by other events, weather, locations, technology,

workload and so on.

How does information enter Police?

Information enters Police in one of these three ways.

Tasked collection

is deliberately sought out and collected.

Routine collection

is collected as a result of another policing activity.

Volunteered information

is given to Police.

s.6(c) OIA

8/24

The Inte gence cyc e

s.6(c) OIA

Consideration of information sources should include:

open and closed source information, i.e., public access information and structured Police systems

Source Protection and security

information management

sanitisation processes compliance with relevant legislation, rules and regulations.

Open-source information

Open source information is any type of lawfully and ethically obtainable information that describes persons, locations,

groups, events, or trends and that exists within the public domain. When raw open source information is evaluated,

integrated, and analysed it potentially provides new insight about intelligence targets and trends. Open source

information is wide ranging and includes:

all types of media

publicly available data bases

directories

databases of people, places, and events

open discussions, whether in forums, classes, presentations, online discussions on bulletin boards, chat rooms, or

general conversations

social media

Government reports and documents

scientific research and reports

statistical databases

commercial vendors of information

websites that are open to the general public even if there is an access fee or a registration requirement

search engines of Internet site contents.

The main qualifier that classifies information as open source is that no legal process or covert collection techniques are

required to obtain the data. While open source data has existed for some time, the prolific use of the internet has

increased its accessibility (and volume) significantly. It can be difficult to assess the accuracy, reliability and objectivity of

open source information.

Raw information obtained from open sources tends to fall into two categories: Information about

individuals and

aggregate information. Issues to consider with open source information include:

what types of open source information about a person should be kept on file by the Police concerning a 'person of

interest' who is not actually a suspect

how aggressive should Police be in gaining open source information on people who expressly sympathise and/or

support crime or a criminal or terrorist group as determined by statements on a web page, but do not appear to be

part of a criminal group or terrorism act nor active in the group

how do Police justify keeping information on a person when a suggestive link between the suspicious person and a

criminal or terrorist group has been found through open source research, but not a confirmed link through validated

and corroborated evidence.

The fact that information is open source should not dissuade an analyst from using it. There can be useful and insightful

information available from open sources. For example, news services have national and international networks of

communications and informants with trained staff to conduct research and investigate virtually all issues that would be of

interest to the public. As a general rule, responsible news organisations also have editorial policies to ensure that the

information is valid, reliable, and corroborated.

As such, the news media is a sound source of information that should be part of an analysts 'toolkit'. However, staff should

note that open source does require special handling, and like any information, needs to be evaluated for reliability and

credibility.

9/24

The Inte gence cyc e

Remember: Inaccurate collection efforts can lead to flawed conclusions, regardless of the analytical tools and skills

employed.

10/24

The Inte gence cyc e

Evaluation

Evaluation is the process of assessing data and information for reliability and credibility.

Admiralty Grading System

As much as possible, all incoming information should be graded using the Admiralty Grading System (AGS), which confirms

SANDA and data reliability and accuracy.

Often information will be reported to an intelligence section or recorded as a noting by Police staff. It is not these staff

members that should be evaluated, but rather the source from which that staff member originally gained the information.

Evaluating sources and data ensures that analysts can approach data with a degree of confidence (or uncertainty as the

case may be), and their subsequent product can then reflect this.

The AGS is used in NIA and CID. It is a two part evaluation:

Reliability of SANDA

Accuracy of information

A Completely reliable

1 Confirmed by other sources

B Usually reliable

2 Probably true

C Fairly reliable

3 Possibly true

D Not usually reliable

4 Doubtful

E Unreliable

5 Improbable

F Cannot be assessed

6 Cannot be assessed

Examples

If. . .

then. . .

a fairly reliable informant passes information that is confirmed by other sources

this is graded (evaluated) as

C1.

a usually reliable source passes doubtful information

this is graded as B4.

a new source or agency passes information which cannot be confirmed by other sources

this would be graded as F6.

and provides no clue as to accuracy

Note: On confirmation it may

change to F1.

Intelligence staff should always consider including the AGS directly within products (quoting it similarly to the Harvard

Referencing System) if either:

the content will raise questions of accuracy

specific and individual pieces of information will likely affect decisions or tactics.

Care must be taken that decisions to record (or not record) the grading of certain pieces of information in an intelligence

report does not inadvertently identify the source (or source type). s.6(c) OIA

11/24

The Inte gence cyc e

Collation

Collation is the process of receiving, logging, storing and cross referencing information so that it can be easily located and

retrieved for analysis. Collation is the fourth part of the Intelligence Cycle.

The collation process ensures that data is reliably received, accounted for, indexed and kept in a logical order. This process

makes it easier to manage and integrate potentially massive volumes of data and information in a way that it can be used

for analysis.

Often cited as a matter of collation, data accuracy and integrity is both an issue of collection and collation. Certainly data

entry can be a function of collation and accuracy is of paramount importance. Human factors will often come into play

where large quantities of data are being manually entered or electronically copied and pasted. Poor quality original data is

not however a matter of collation. That said, this may require data cleaning or formatting to occur at the collation stage.

While in many cases intelligence staff do not have line control over data entry staff, Intelligence staff should advocate for

and champion both the need for capturing notings and data, and accurate data entry. Collation includes the management

of the collated data once in its storage medium or database, and the subsequent production of initial collation summary

products such as graphs, charts and spreadsheets etc. These often serve as preliminary supporting products to commence

or enable the analysis process.

12/24

The Inte gence cyc e

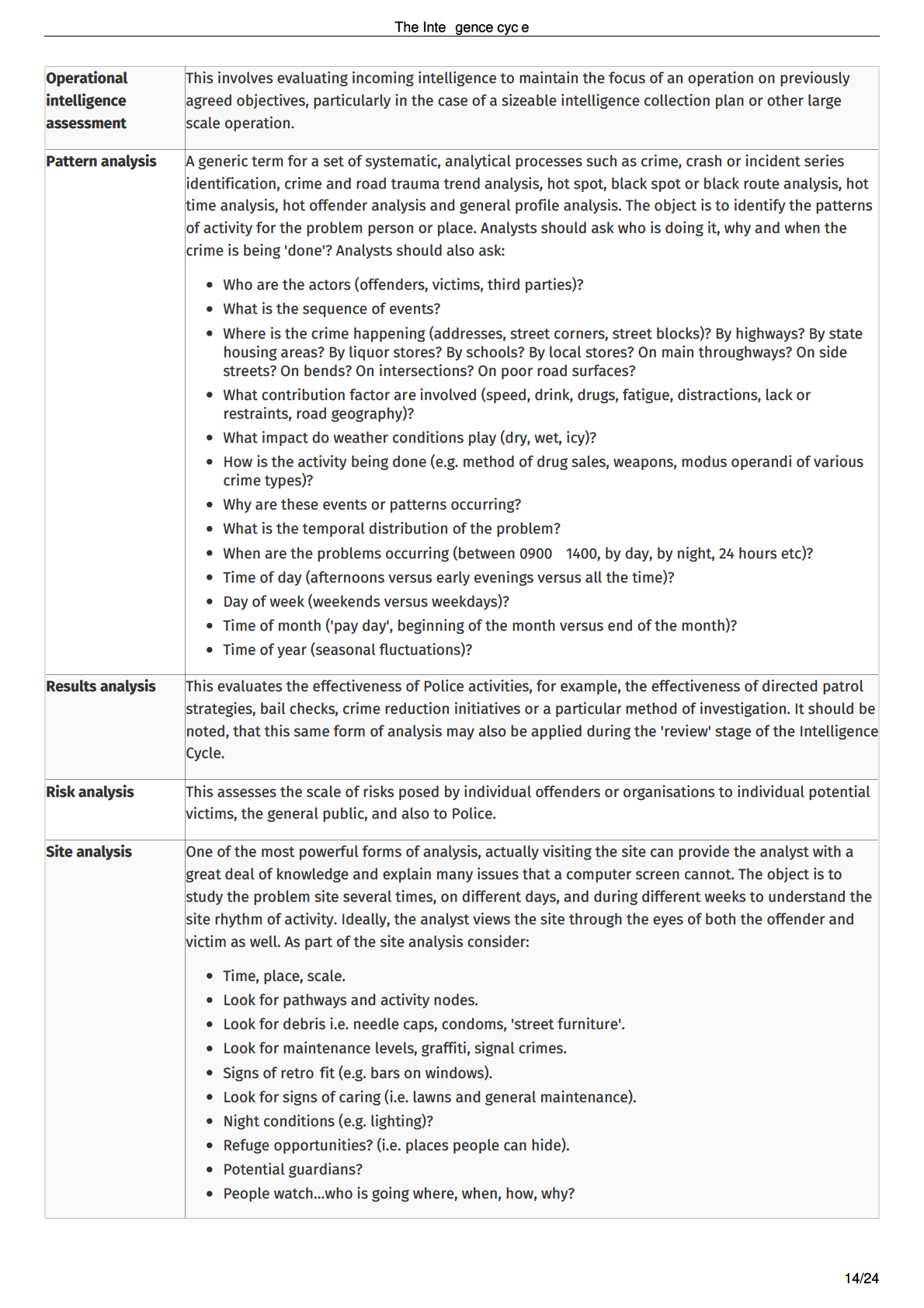

Analysis

This section contains the following topics:

What is analysis?

Types of analysis

Criminal business profiles

Demographic/social trends analysis

Market profiles

Network analysis

Operational intelligence assessment

Pattern analysis

Results analysis

Risk analysis

Site analysis

Subject profile analysis

Use analysis

User analysis

Inference Development Model

What is analysis?

Analysis is the converting of raw information into an intelligence product by breaking down that information into its

component facts and inferences, then integrating these with existing information and intelligence holdings to identify

patterns and trends (or the lack thereof). In criminal intelligence, the identification of root causes and drivers of defined

problems is also a critical function of analysis.

The interpretation of the resulting conclusions is what produces intelligence. The most fundamental interpretation method

is to ask the '5WH' interrogatives:

who,

what,

when,

where,

why and

how? Similarly, the application the questions 'so what?'

and 'what does this mean' allow analysts to consider implications and focus on predictive conclusions. This also helps to

avoid common pitfalls of simply restating facts or describing the collated information.

Types of analysis

The use of defined analytical techniques and products, created using recognised structured analytical tools and methods,

is fundamental to the development of intelligence products. The specifics of the situation will determine the number and

combination of analytical techniques and products that should be drawn on to inform intelligence product requirements. A

greater understanding of the problem can be acquired by overlaying the results of analytical work. Analytical options

include, but are not limited to, those shown in this table.

Criminal business

These contain detailed analysis of how criminal operations or techniques work, in the same way that

profiles

a legitimate business might be explained.

Demographic/social This is centred on demographic changes and their impact on crime and road trauma. It also analyses

trends analysis

social factors such as unemployment and homelessness, and considers the significance of population

shifts, attitudes and activities.

Market profiles

These are continually reviewed and updated assessments that survey the criminal market around a

particular commodity, such as drugs or stolen vehicles, or of a service, such as street prostitution, in

an area.

Network analysis

This not only describes the links between people who form criminal networks, but also the

significance of these links, the roles played by individuals and the strengths and weaknesses of a

criminal organisation.

13/24

The Inte gence cyc e

Probability statement

Qualitative statement

% Probability

ALMOST CERTAIN

The event will occur in most circumstances

>95%

LIKELY

The event will probably occur in most circumstances

>65%

POSSIBLE

The event might occur at some time

>35%

UNLIKELY

The event could occur in some circumstances

<35%

RARE

The event may occur in some exceptional circumstances

<5%

(Source:

Looking ahead with confidence: our Organisational Risk Approach, New Zealand Police Risk, Assurance and

Governance Group, 2n

d Edition, 2014)

16/24

The Inte gence cyc e

Responses

This section contains the following topics:

What are responses?

Purpose of responses

What are responses?

Fundamentally, responses are attempts to describe an action based solution to an identified problem following analysis.

They broadly aim to prevent and reduce crime.

The SARA problem solving model developed in the United States of America in the 1980s and usually attributed to John Eck,

defines responses as:

Brainstorming for new interventions.

Searching for what other communities with similar problems have done.

Choosing among the alternative interventions.

Outlining a response plan and identifying responsible parties.

Stating the specific objectives for the response plan.

Carrying out the planned activities.

(www.popcenter.org)

Responses are often couched under the heading of 'Recommendations'. Debate in the intelligence community continues as

to the validity and legitimacy of intelligence analysts posing recommendations to decision makers.

Ultimately, it should be made clear to both analysts and decision makers that recommendations are simply that. They are

not binding directions to act. Analytical recommendations may be strengthened by use of credible and applicable research

and the input of subject matter experts and operational practitioners. There will never be a compulsion for decision

makers to act on analytical recommendations, the final decision being theirs alone this is the essence of command

responsibility.

Purpose of responses

Responses should be considered with a view to answering these questions:

How can we reduce the opportunity to offend?

How can we reduce the offender's desire (motivation) to offend?

How and when can we increase the likelihood of apprehension / increase the 'risk' to the offender?

How and when can we reduce the suitability of targets to the offender(s)?

How and when can we increase the 'capable guardianship' around places, products and people (victims)?

Another way to consider responses is to consider the 'mechanism' by which the response reduces or prevents crime, using

situational crime prevention techniques (

Tilley, 1998). Tilley outlines 25 techniques under the headings:

Increase the effort (for the offender)

Increase the risks (for the offender)

Reduce the rewards (for the offender)

Reduce the provocations (for the offender)

Remove excuses (for the offender).

17/24

The Inte gence cyc e

Dissemination

This section contains the following topics:

What is dissemination?

Four standard product types

Core intelligence products

Knowledge products

Analytical products

Frontline Intelligence (FLINT)

Linking products and decision making

Know who the key decision makers are and how to influence them

Decision makers are rarely intelligence professionals

Pick the right presentation style and format

Decision makers are faced with multiple, competing demands

Know what is important

Seek clarity on what decision makers expect

Focus on people and context

Key decision makers may be outside the immediate policing environment

Be aware of the constraints on decision making

What is dissemination?

Dissemination is the communication and distribution of raw or finished information or intelligence to decision makers and

consumers. The fundamental tenet of dissemination is to get intelligence to those who need it, and have the right to use it,

in whatever form is deemed most appropriate, in time for it to be useful.

Four standard product types

New Zealand Police disseminate intelligence through verbal briefings and by these four standard intelligence product

types.

Core

Such as the strategic and tactical assessments and problem and subject profiles.

intelligence

products

Knowledge A Knowledge Profile provides an overview of a general topic or issue and serves to highlight current

products

knowledge and specific areas of concern or priority.

Analytical Such as pattern analysis, market profile, road trauma risk profile, road user analysis, crash analysis, RSAP road

products

safety risk assessment, network analysis, criminal business profile, operational intelligence assessment, result

analysis, risk analysis and environmental trend analysis.

Frontline

Such as subject profiles, intelligence reports and, at times, special notices. Increasingly disseminated by via

Intelligencemobility platforms.

(FLINT)

To be fully effective (and acknowledging the reality of resource constraints) intelligence units need to be able to generate

a wide range of outputs. With mobility platforms becoming more accepted medium for intelligence reporting, and other

technological innovations, analysts should seek to be innovative in their dissemination.

The production and dissemination of strategic products is particularly important if decision making within individual

districts is to avoid a recurring emphasis on short term, response and/or incident focused policing.

A combination of well directed strategic, operational and tactical intelligence products will provide a robust reporting

18/24

The Inte gence cyc e

framework that will enable decision makers to align policy, resources and responses with objectives and priorities.

Linking products and decision-making

Know who the key decision-makers are and how to influence them

Usually, decision makers are identified from the organisational hierarchy chart, but other key individuals may not appear

on it. For example long standing and experienced detectives will often have significant influence over how investigation

units work, even if they have no formal management responsibility. Equally, a crime or road trauma reduction strategy may

require the involvement of partner agencies whose direct interests may be quite different to Police. Identifying and

understanding how key individuals operate, what their interests are and how they see the world will often be important in

influencing how intelligence outputs are received and subsequently used.

Decision-makers are rarely intelligence professionals

This usually means that they need clear, straightforward advice written in a language free of jargon and complexity. To be

useful, intelligence products need to be written for the decision maker and not for other intelligence professionals. They

should also be short: all decision makers are time poor.

Pick the right presentation style and format

For many analysts lengthy written reports or detailed briefings, backed by extensive data, may appear to be the only way

to 'get the message across'. These are often necessary and important, but in reality, there are many other, and often better,

ways in which to communicate material. According to the management guru Henry Mintzberg, "It is more important for the

manager to get… information quickly and efficiently than to get it formally" (

Mintzberg, 1973).

Some options to consider are listed in this table.

19/24

The Inte gence cyc e

VisualisationMany people prefer to receive information visually, e.g. as mind maps, link charts and 'pictures'. While there

are multiple software programmes that will provide high quality charts, spreadsheets or maps, it is important

for decision makers to understand that while they support and facilitate effective presentation

they do not

represent the actual analysis. Deciding what to map, how to manipulate data in a spreadsheet or represent

information on a timeline is analytical the visualisation product itself is not a substitute or proxy for the

thinking (analytical) element of the intelligence process.

One-to-one These allow for two way questions and answers, can often supplement written reports, and are an effective

informal

way to quickly get the main points of a message across. For information to flow effectively, analysts must be

briefings

embedded around and have access to decision makers at every level.

Text and

E mail has become the major tool for communicating but in some places the sheer volume of information

electronic

that requires attention can be overwhelming. This means analysts need to find ways to differentiate their

messages

product. This doesn't mean marking emails 'urgent' or using bold coloured fonts. Instead, develop a

reputation for being the sender of short, clear, relevant messages that are always of value to the recipient.

Corridor

Often the opportunity to influence arises at odd and unexpected times. Meetings in the meal room, in the

sessions

lunch queue or riding the lift together are often key moments in winning time and attention. A brief exchange

of views and ideas can often lead to more substantial analysis. The ability to network effectively both

formally and informally is a critical skill.

Visibility

Getting out from behind the computer terminal and being seen around (for example, turning up to listen to

the Police Commissioner's speech to a local business group) and offering general views and ideas about

policing will create an expectation that the analyst already has something to offer. Sharing good news,

making a point of explaining the impact of a piece of work, contributing to newsletters and so on, all create

visibility, making it more likely that when the intelligence product arrives on the decision maker's desk that

it is seen as coming from a person that already has valuable ideas to offer.

Understand In policing many analysts have no idea what happens to their products and therefore little or no idea about

the power of the impact they have made. Knowing what style and format works is clearly important. The overall message is

different

summed up by

Gardner (2004 p.101); "Individuals learn most effectively when they can receive the same

formats

message in a number of different ways, each re presentation stimulating different intelligence".

Decision-makers are faced with multiple, competing demands

Intelligence may be important in making choices, but other factors will also weigh heavily. A long running media campaign

against a particular crime problem or a sensational headline will often set the agenda. Though such issues may appear to

be a distraction they cannot be ignored. Intelligence has an important role to play in helping decision makers to deal more

effectively with these problems.

Know what is important

Generating intelligence products and firing them out in the hope that 'something' will stick is a recipe for frustration and

failure. Decision makers with few staff and policing a limited geographical area need products with a distinct, detailed and

well informed local flavour. Area commanders may expect to see what the common issues are and where opportunities

exist for attacking shared problems while district commanders and national managers will normally require a broader,

more strategic viewpoint that perhaps addresses a problem from a whole of organisation, or even whole of government

approach. It is very unlikely that a single report will adequately address each need or interest and analysts need to

determine what's important at each level.

Seek clarity on what decision-makers expect

Decision making priorities are often ill defined and subject to change. New requirements can emerge very quickly and

what was a major issue last week can be off the agenda today. For analysts this means staying in touch with the latest

thinking so that outputs can be directed at the right issues. Agreeing terms of reference with clear objectives and keeping

20/24

The Inte gence cyc e

these updated will help, but effective, frequent communication is vital. Crucially, analysts must know who they are writing

for and why the product is needed. In most agencies decision making will go on regardless of whether or not the

intelligence picture has been painted, and adding real value is about the ability to deliver the right product, in the right

format at just the right time.

Focus on people and context

"If you are interesting people will want to be with you. People will seek your company. People will enjoy talking to you…"

(

De Bono, 2004). The best analysts have presence, engage in effective verbal and non verbal behaviour, and have the

ability to read a situation and tailor their contribution accordingly. While these may be qualities that appear intangible

they can be practised and when used successfully will contribute to the impact made.

Key decision-makers may be outside the immediate policing environment

The drive towards multi agency partnership working and the blurring of lines of responsibility that accompany the move

towards a more holistic all of government approach to tackling crime, leads to a more complex and flexible decision

making environment. This has clear implications for police intelligence which needs to respond effectively to such new

demands.

Be aware of the constraints on decision-making

All law enforcement decision makers operate in a world of finite budgets, limited resources and time constraints. Most are

burdened with the expectations of more senior managers, organisational performance regimes, and unmet public

expectations. Equally, the introduction of electronic forms of communication has significantly increased the amount of

information circulating to managers. All of this is competition for analysts. Intelligence outputs that fail the test of real

world understanding are likely to be of limited value, and analytical units that establish a reputation for being

disconnected from the day to day realities of policing will generally find it difficult to have any meaningful input to

decision making.

21/24

The Inte gence cyc e

Review

This section contains the following topics:

Feedback

Components of good products

Products will be better informed by involving others

Well written products do not confuse facts and opinions

Good analysis needs to add real value

Timeliness is always a factor

Executive summaries are key to focusing attention

Good products get to the point

Experience for Police officers is mainly about evidence

Good law enforcement analysis

Products must comply with policy, procedure and legislation

Review is the task of examining intelligence processes and products to determine their effectiveness, and the responses in

terms of their effect (impact) on the criminal environment.

Often analysts and intelligence units do not know what has happened to or with the intelligence they provide to decision

makers or whether it has been effective. It is axiomatic that intelligence staff will often hear 'when they got it wrong,' and

traditionally, negative feedback has been more forthcoming than positive or constructive commentary. Any formal or

informal mechanism which can structure feedback and review of analytical effort is to be encouraged.

Review is both a critical part of the New Zealand Police Intelligence Cycle but also the cross cutting organisational

competency of

challenging for continuous improvement.

Feedback

There is often no formal method for tracking and evaluating intelligence product therefore one way to review it can be to

include a feedback form with each product that is disseminated. Feedback forms, if used, should ask specific questions

relating to the usefulness of the intelligence and the appropriateness of the dissemination method.

The simple form consists of several open ended questions about the product, which the end user is asked to complete

and return to the originator. The questions gauge how the intelligence was used, if it was not used then why not, what its

value was, and how it could have been made better.

The feedback has additional value in that the analyst becomes privy to the value and quality of their product as others see

it. The end result is intelligence that is used and valuable, and intelligence products and practitioners that become

increasingly more efficient and effective over time. Intelligence supervisors can also use the feedback to assess the value

of their unit's products, to assist in assessing unit productivity, and to assist in individual performance monitoring. The

feedback may also be helpful to support existing or request additional resources.

It should be stressed that a feedback form will never have the accuracy, timeliness, or even for that matter, frankness, as

that of face to face feedback made directly with consumers (internal and external). This method of evaluation should be

preferred over feedback forms which often are simply not completed.

Analysts and intelligence units are strongly urged to know and understand their decision makers' requirements, priorities,

challenges and preferences. A professional relationship where candid and frank feedback can be sought and given is the

ideal in terms of providing effective, responsive intelligence.

Similarly, where intelligence and analysis is used to support an operation, investigation, major event or project, the

opportunity should be taken to honestly debrief the activity and identify lessons learned. This should encompass strengths

and opportunities as well as well ineffective processes and weaknesses.

Components of good products

22/24

The Inte gence cyc e

"The better you understand your subject the more likely you can produce material with insight" (

Pease, 2006)

This may seem obvious but too often analysts work with single data sets or information streams, fail to read widely around

their subject, and miss the latest research or thinking. There are different ways to think about problems and there are

many fields outside law enforcement medicine, geography, science, mathematics, philosophy, business that all have

ideas, concepts and methodologies that can assist effective crime and road trauma intelligence analysis. By limiting

solutions to traditional fields it may be possible to make a short term or marginal difference but real progress is likely to

require new (or at least innovative) thinking. The best analysts have a broad view of the world around them and can

effectively apply the learning from other disciplines.

Products will be better informed by involving others

A community or neighbourhood profile for example will always benefit from input of those working closest to the problems

on the ground. Consultation and taking advice is essential a computer system and its captured data only contain some of

the information necessary for effective analysis.

Well written products do not confuse facts and opinions

Confusing fact with opinion can lead to criticism, and at worst it can lead to flawed decision making and action. The

separation of facts, evidence, opinions, judgments, hypotheses, conclusions and recommendations is a critical element of

the analytical tradecraft and fundamental to the generation of effective product.

Good analysis needs to add real value

The biggest criticism of many intelligence products by operational staff is that they simply provide 'news and weather'

information already known about events that have occurred and with no sense of how they relate to the future. Analysts

should avoid the temptation to simply reorganise or represent information that is already widely available. This will

become increasingly challenging in the District Command Centre environment where reporting timeframes are becoming

more and more compressed.

Timeliness is always a factor

There will always be intelligence gaps (unknowns) and it is usually the case that conclusions and recommendations need to

be made on incomplete data. But this needs to be set against the fact that timeliness in the dissemination of an

intelligence product is almost always critical and this will often mean exercising judgement about when to publish or

report. Though negotiation around deadlines can help it takes insight and bold analytical decision making to know when

to call it a day

Executive summaries are key to focusing attention

Analysts will often know that a subject is complex and that reaching a clear and firm view can be difficult, but for decision

making simple is often best. For analysts this is a particular challenge and writing accurately and in a style that allows non

experts to understand the argument and action the product is a skill that needs significant practice. Lengthy products, for

example, may never be read in full by busy decision makers. Using an executive summary, stressing key findings and

highlighting action points may all be essential to focus attention on the right issues.

Good products get to the point

There is a temptation for analysts (particularly those new to the field) to want to 'show all their workings'. Sometimes this

may be necessary or needed, but in general such detail is best avoided in the main body of a report. The 'noise' it creates

can often detract from the main message. Detailed workings need to be available to defend any challenge, but it shouldn't

be necessary for them to be fully reported, particularly in a situation where analysts and decision makers have confidence

in their respective roles.

Experience for Police officers is mainly about evidence

In writing for a policing audience it is important to remember that the search for facts is often paramount. Poorly drafted

prose that meanders across a chosen subject, or reports written in the style of a work of fiction are unlikely to positively

influence serious decision making and make the task of the intelligence unit harder. That said, it is not an analyst's role to

23/24

The Inte gence cyc e

seek evidence to a forensic level it is simply not possible to do this and simultaneously be future focussed and

predictive.

Good law enforcement analysis

Good law enforcement analysis should be bold (but not foolhardy) and seek out the truth. Good analysts bring a

professional, objective approach to law enforcement. If analysts don't make decision makers uncomfortable at least some

of the time then it's likely that they are not doing their job properly.

Products must comply with policy, procedure and legislation

This is particularly the case where sensitive intelligence is concerned. This means recognising the need to know principle

(balanced against the principles of need to share); adherence to any restrictive disclosure obligations for example

criminal justice sector partners will often place limits on what can be done with their intelligence products; and most

products should bear an appropriate security classification. It is important that intelligence officers and analysts

understand these issues because slack application of the rules will undermine trust and confidence and may threaten

sensitive sources or operations. Equally, over classified material, which is too tightly controlled, can seriously hamper the

effective use and application of products for decision making. The observation "if I can't use it don't tell me about it" is

still a familiar (and wholly flawed) comment heard in many police investigation units.

Version number:

3

Owner:

Director: National Intelligence

Publication date:

06/03/2015

Last modified:

26/09/2017

Review date:

06/03/2017

Printed on : 01/04/2021

Printed from : https://tenone.police.govt.nz/pi/intelligence cycle

24/24

Issue motivated and protest groups' intelligence

Table of Contents

Table of Contents

2

Purpose

3

Background

3

When can nte gence be co ected?

3

Enter ng and query ng nte gence n NIA

3

Procedure for en er ng n e gence n o NIA

3

Re ated nformat on

7

Issue mot vated and protest groups' nte gence

s.6(c) OIA

s.6(c) OIA

5/8

Issue mot vated and protest groups' nte gence

Version number:

1

Owner:

Director: National Intelligence

Publication date:

16/03/2016

Last modified:

01/12/2020

Review date:

16/03/2018

Printed on : 01/04/2021

Printed from : https://tenone.police.govt.nz/pi/issue motivated and protest groups intelligence

8/8

Introduction to Intelligence

Table of Contents

Table of Contents

2

Summary

3

Overview of intelligence

4

Prevention First: Intelligence Operating Strategy

5

Intelligence people and products

6

Co ect ons

6

Informat on management

6

Ana ys s

6

Management

6

Inte gence products

6

Dep oyment and the f ve Prevent on F rst pr or ty areas

6

Prepare for p anned events

7

Work w th partner agenc es

7

Ma nta n a prevent on m ndset

7

Th nk 'cr me tr ang e'

7

3i model

8

Interpreting the criminal environment

9

Influencing decision makers

10

Decision makers' impact

11

Introduct on to Inte gence

Summary

This section contains the following topics:

Overview of intelligence

Prevention First: Intelligence Operating Strategy

3/11

Introduct on to Inte gence

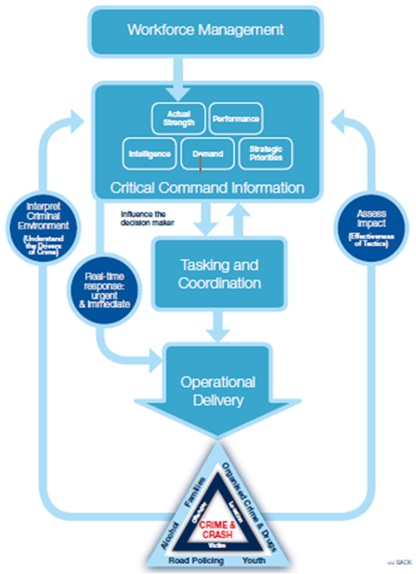

Overview of intelligence

The goal of Intelligence in Police is to enable decision makers to prevent crime and road trauma problems and promote

safe communities. It achieves this goal when it provides accurate, timely and actionable advice to decision makers that

nforms and supports operational activity and contributes to the achievement of organisational objectives.

ntelligence is a key component of Police Critical Command Information (CCI), which underpins the Prevention First

National Operating Strategy. It is used to inform and drive the deployment of operational resources, enable understanding

of the criminal environment and facilitate evidence based action, particularly in respect of priority and repeat victims,

offenders and locations.

ntelligence includes people, products, processes and partnerships.

The intelligence process is an interpretative one that has analysis at its heart. The intelligence cycle guides this process. It

entails the collection, evaluation, collation and analysis of information from a diverse range of sources and agencies. The

analysis component integrates relevant information to form a cohesive understanding of a problem or environment, and

nterprets that understanding so that decision makers can decide what action to take. Intelligence draws conclusions and

nferences from facts and patterns. It anticipates future behaviours, and identifies trends and risks. It is future focused.

The intelligence cycle is completed by the formulation of responses to defined problems, timely dissemination to clients

and stakeholders, and review of effectiveness of both products and processes. It is iterative and dynamic not linear and

sequential.

ntelligence outputs are intelligence products, which take different forms depending on the end use and intended

audience. Intelligence products must have a customer: intelligence should add value to information and should be

actionable.

ntelligence is critical for decision making, planning, targeting, and crime and road trauma reduction as well as community

safety. Police depend on intelligence at all levels, and cannot function effectively without good intelligence.

4/11

Introduct on to Inte gence

Prevention First: Intelligence Operating Strategy

The intelligence process is focused on interpreting the criminal and crash environment and informing decision makers so

they can have a real impact in directing the policing response. In turn, decision makers influence intelligence by setting

priorities and requesting intelligence products. See: Intelligence Operating Strategy.

nte gence-operat ng-strategy.pdf

2.93 MB

5/11

Introduct on to Inte gence

Intelligence people and products

Collections

Intelligence Officers (IOs)

Field Intelligence Officers (FIOs)

Intelligence Collections Coordinators (ICCs).

Information management

Intelligence Support Officers (ISOs)

Intelligence Support Assistants (ISAs).

Analysis

Trainee Analysts

Analysts

Senior Analysts

Lead Analysts.

Management

Intelligence Supervisors

District Intelligence Supervisors

District Managers of Intelligence (DMIs)

National Intelligence Centre (NIC) Managers

National Manager: Intelligence.

Each role has specific functions that relate to its part of the model, and each requires specialist training to carry out those

functions. The roles and functions are set and governed by the Professional Development in Intelligence Programme

(PDIP), which is administered by the National Intelligence Centre.

Intelligence products

The Police intelligence product framework is designed to support staff at all levels from frontline officers to middle and

senior management through a combination of:

Core intelligence products regular action oriented outputs generated within areas, districts and nationally, to drive

daily operational activity.

Analytical and knowledge products which provide insight into specific problems family violence, burglary, road

policing, serious crime investigations etc to drive short, medium and longer term decision making and resource

allocation.

Frontline products (including FLINT) designed to improve situational awareness of supervisors and frontline officers

and a core opportunity within the Police mobility programme

Deployment and the five Prevention First priority areas

Intelligence will:

target active offenders

constantly scan the criminal and crash environment and identify opportunities for action focus advice to key local

decision makers, particularly Area and District Commanders

maximise forensic intelligence opportunities act urgently, particularly around persistent offenders

use intelligence products to understand trends and patterns in the criminal and crash environment and set priorities

in tasking & coordination meetings

encourage frontline staff to routinely submit quality notings to develop the intelligence picture

usually require production of a range of intelligence products over an extended period of time to solve persistent

problems

use the VOLT (Victims, Offenders, Locations, Trends) report to inform the targeting of repeat/priority offenders,

6/11

Introduct on to Inte gence

victims, locations

support short medium term (tactical) interventions and longer term sustainable interventions (treatments).

Prepare for planned events

Intelligence will:

highlight key events up to 3 6 months ahead to enable planning and resource allocation decisions

support and staff a Joint Intelligence Group where deemed necessary for major pre planned events and know how

it operates

maximise the use of the RIOD (Real Time Intelligence for Operational Deployment) platform to deliver timely

intelligence.

Work with partner agencies

Intelligence will:

develop jointly owned intelligence products (JOIPs) with key partners share information in accordance with agreed

protocols

work with partners to leverage their available knowledge and resources to support joint priorities

share intelligence skills, knowledge and resources to build cross agency capacity and capability

explore opportunities for joint problem solving with partners.

Maintain a prevention mindset

Intelligence will:

deliver timely intelligence in support of District Command Centres

use forward looking intelligence products to focus staff time, effort and interventions on 'preventing the next crime

and crash'

deliver intelligence products focused on emerging or persistent policing and community problems

link intelligence with other components of Critical Command Information to inform deployment

act with urgency particularly in respect of active offenders and emerging trends and problems.

Think 'crime triangle'

Intelligence will:

focus on victims, offenders and locations

use qualified analysts and other experts to apply crime science and situational crime and crash prevention theories.

7/11

Introduct on to Inte gence

3i model

This section contains the following topics:

Interpreting the criminal environment

Influencing decision makers

Decision makers' impact

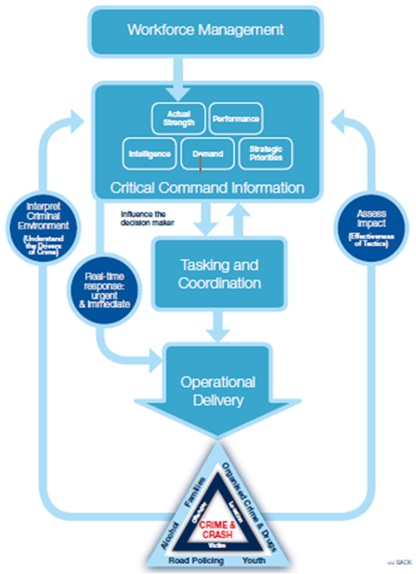

The intelligence process is focused on interpreting the criminal and crash environment and informing decision makers so

they can have a real impact in directing the policing response. In turn, decision makers influence intelligence by setting

priorities and requesting intelligence products.

The 3i model consists of three inter related elements:

the criminal environment

intelligence

decision makers.

Intelligence includes processes, products and people, and in the 3i Model 'intelligence' means all three.

These elements are linked by three processes:

interpret

influence

impact.

The model provides a consistent, integrated and cohesive approach to reduce crime and victimisation. To be successful

each part of the model must be operating effectively.

8/11

Introduct on to Inte gence

Interpreting the criminal environment

ntelligence needs accessible and reliable information to identify actual and perceived crime and road trauma problems.

One of the key tenets of intelligence led policing is that every Police employee is a collector of intelligence. The onus is on

the collector to record and advise the appropriate intelligence unit of any information relating to emerging crime including

organised crime, and road trauma.

ntelligence uses information to develop intelligence products (documents) that identify patterns in crime or road trauma

and practical ways to disrupt them. Identifying patterns and problems depends on in depth situational awareness.

ntelligence focuses on crime and road trauma problems that have the greatest impact on offending rates. These include

hot locations (time and space), hot targets (victims and commodities), and hot offenders.

9/11

Introduct on to Inte gence

Influencing decision makers

Discussion between intelligence staff and decision makers about intelligence products is an essential part of the 3i model.

Delivery of an intelligence product must be based on clear direction and priorities from decision makers, usually set in a

tasking and coordination meeting.

The aim of the interactions is to ensure intelligence activities are focused on priorities, products are timely and useful, and

suggested actions will have the desired effect.

10/11

Introduct on to Inte gence

Decision makers' impact

s decision makers, Police and appropriate partners respond to the identified crime or road trauma problem and take

action in order to have an impact on the crime and road trauma environment. Effective use of well directed Police and

partner activities are the actions taken to reduce crime and road trauma.

Version number:

6

Owner:

Director: National Intelligence

Publication date:

06/03/2015

Last modified:

26/09/2017

Review date:

06/03/2017

Printed on : 01/04/2021

Printed from : https://tenone.police.govt.nz/pi/introduction intelligence

11/11

Intelligence products

Table of Contents

Table of Contents

2

Executive summary

3

Standardised intelligence product templates

4

Make-up of the product suite

5

Intelligence Instructions

6

RIOD

7

Intelligence Framework

8

Intelligence Indicators

9

Intelligence Report (IR)

10

Subject Prof e

10

VOLT

10

FLINT

10

Da y Assessment

11

Inte gence products

Executive summary

Intelligence assessments (products) enable Police commanders to acquire an understanding of the criminal environment

they have the responsibility for. In general, Intelligence assessments enable accurate and timely decision making and drive

the tasking and coordination process.

Key, critical points for staff to note:

Standardised intelligence product templates, loaded into the NZP Intelligence RIOD site, must be used.

All intelligence assessments, unless there is sensitivity, must be created in the RIOD site and published to it.

3/11

Inte gence products

Standardised intelligence product templates

A number of standardised intelligence product templates have been in use since 2007. These have been reviewed several

times to ensure they remain relevant. The most recent review was conduct in 2015 and looks to provide templates that

meet current requirements and are aligned with the 2015 Intelligence Roadmap.

The templates are designed to work with the Police mobility strategy, in that they can be disseminated to staff and decision

makers in a broader range of methods to enable them to be read on mobility devices or accessed via RIOD.

4/11

Inte gence products

Make-up of the product suite

The product suite has been designed to provide a small range of templates to meet the needs of clients at District and

National level.

Template

Primary use

Intelligence

To indicate problems and trends at a strategic level requiring additional analysis

Indicators

Intelligence ReportA tactical, Operation and Strategic template for decision making

Subject Profile

A comprehensive profile of an individual, location or commodity

VOLT

An assessment designed to identify deployment opportunities to short / medium term problems (two

weekly or monthly)

FLINT

Information to front line staff

Daily assessment Summarise activity in the previous 24 hours and identifies opportunity for immediate deployment

5/11

Inte gence products

Intelligence Instructions

Since 2009 each product template has been supported by a set of guidelines. The new templates are more flexible for the

analyst to determine what is required for the client, however they are accompanied by a clear set of Instructions that are

designed to force analytical rigour within the assessment.

6/11

Inte gence products

RIOD

All templates will be loaded into the NZP Intelligence RIOD site. Assessments must be created in the RIOD site to provide

intelligence staff with visibility of assessments being undertaken by analysts. It will provide the National Manager:

Intelligence visibility of all assessments being conducted across NZP.

RIOD will also provide a point of storage for the following:

Storage

Working folder Subject Profile

Storage of Word doc's for update. Intel access only.

Working folder

Storage of all draft Word assessments. Intel access only.

Published folder

Where completed assessments are published. All RIOD user access.

All assessments, unless there is sensitivity, must be created in the RIOD site and published to it. A set of RIOD user

instructions is available here via the Systems Manager. Some assessments created for specific operations or exercises will

be locked down to provide access only to specific users.

The RIOD process is consistent with that of a Joint Intelligence Group (JIG). It provides familiarity should a District need to

activate a JIG in response to a threat or exercise.

7/11

Inte gence products

Intelligence Framework

The Intelligence Product Framework diagram highlights the six assessments and their primary use and client. The Flint is an

immediate term report primarily for communicating valuable information to front line staff. In contrast the Intelligence

Report (IR) is designed to be flexible enough to provide analysis on a range of tactical, operational and strategic

assessments. The primary client is a decision maker.

8/11

Inte gence products

Intelligence Indicators

Intelligence Indicators is a short one paragraph first level assessment of an emerging trend or risk, often at the strategic

level. At a District level the indicator may reflect Area deployment needs. It has replaced the Tactical Assessment, and is

designed to give the decision maker an introductory understanding of an emerging or chronic problem.

The decision maker will then determine if the problem is one they require further information on or are likely to deploy to.

If so, the Intelligence manager and the decision maker can agree to conduct a more detailed analytical assessment of the

problem.

A range of indicators can be raised to decision makers at one time, however unlike the Tactical Assessment the Intelligence

Indicators process is designed to raise a trend or problem at a time where the issue or problem is current. There is no

requirement to wait for the monthly tasking and coordination meeting to raise an Intelligence Indicator.

s.6(c) OIA

An indicator will briefly describe the problem and its potential size or impact. It will also indicate the benefits deeper level

analysis will provide.

Once tasked to undertake deeper analysis the Intelligence Report (INTREP) template should be used.

A detailed set of instructions are provided with the Intelligence Indicators process. The Instructions replace previous

Tactical Assessment guidelines.

9/11

Inte gence products

Intelligence Report (IR)

The Intelligence Report (IR), often referred to as the INTREP, is the primary document Intelligence uses to present findings

of analysis and make recommendations relating to a Crime, Road Safety or Community Safety problem.

It is a product that can be requested by a decision maker or tasked by and Intelligence Manager. It is flexible to the needs

of the particular analysis being conducted. For quick intelligence reports at a district level, the analyst may choose not to

include several sections (e.g. Contents or Key Findings) of the template, but for more strategic analysis the analyst may

include all sections and include an A3 summary as well. The template is designed so the client can read the Key Findings

and Recommendations sections and gain a clear understanding of the problem. A set of instructions for the use of the

INTREP template are to be followed.

The IR template can be used for a wide range of assessments including the following:

the activities of an individual or group (criminal, traffic and community safety)

an individual victim or trend in victimisation

a problem with a specific location (crime trend in a specific geographical location)

crime problem

strategic or knowledge assessment

road safety assessment

problem profile

any other intelligence requirement that can be tasked to.

When the activities of a person are required to be analysed, historic practices require a decision maker subject profile

template to be used. This has changed and the IR template is now to be used. The primary reason for this is discussed in

the Subject Profile section. The structure of the template allows for operational decisions to be made in respect of that

individual as either an offender or a victim.

Subject Profile

The Subject Profile can be about an individual a location or a commodity. It will be the one Intelligence product to record

information about a particular person, location or commodity. Each Profile will have an updated assessment section.

Example: An offender has a subject profile that covers a wide range of information about that person including

victimisation, offending, and risk. If additional information suggests that person needs to be deployed to an IR template

will be used to present an assessment of all new information in combination with existing information held in the Subject

Profile. The IR is the taskable document that goes to the decision maker, however the analyst will then use this new

analysis to update the offenders Subject profile. This will mean there could be numerous IR's relating to the activity of an

individual, but there will only ever be one Subject Profile of that person.

All Subject Profiles, both District and National, will be stored in word format compartment in the NZP Intelligence RIOD site

that is only visible to intelligence staff. All subject profiles will additionally be saved in pdf and stored in the NZP

Intelligence RIOD library for general access by Police.

The subject profile must contain the most recent information about the person, location or commodity, and will have a

short assessment that provides a quick snapshot of the risk.

VOLT

This assessment is one that is not mandatory but where used is designed to provide opportunity for decision makers to

make deployment decisions to acute chronic crime problems. As opposed to the Daily assessment, it will consider Victims,

Offenders, Locations and Trends that need to be impacted upon. E.g., a daily assessment will identify incidents that are

occurring in a 24 hour period that are consistent with existing medium to long term crime problems previously identified in

the VOLT.

FLINT

10/11

Inte gence products

A FLINT product is a short 1 page information report that relates to a 'Person, Vehicle or Other topic' that is required to be

communicated to front line staff for their awareness. Often FLINT's will convey staff safety risks, or relate to high

risk/volume offenders that are required to be apprehended.

They are communicated to front line staff mobility devices via the District Command Centres.

Daily Assessment

The Daily assessment is an electronic product that is the result of a daily scanning process. It is designed to provide

decision makers with tactical forward looking opportunities to impact on individuals (wanted people, increase

victimisation) and locations that pose a risk if not deployed to. It may summarise occurrences occurring in acute or chronic

problem locations that have been analysed in the VOLT. It is used in daily tasking meetings.

Version number:

3

Owner:

Director: National Intelligence

Publication date:

08/03/2016

Last modified:

26/09/2017

Review date:

08/03/2018

Printed on : 01/04/2021

Printed from : https://tenone.police.govt.nz/pi/intelligence products

11/11

Intelligence for investigations

Table of Contents

Table of Contents

2

Executive summary

4

Overview

5

Purpose

5

Va ue

5

In e gence as a phase

5

Ro es and respons b t es

5

Cha n of command

6

Process

7

Genera pr nc p e

7

In t a scop ng

7

Terms of reference

7

Estab shment

7

T meframes

8

Resources

8

Accommodat on

8

Inte gence correspondence process

8

Ongo ng rev ew

8

People

10

Pr nc p es

10

Structure

10

Superv sor

10

Func on

11

Pre requ s es

11

Sk s and know edge

11

Ana yst (Lead, Sen or or Ana yst)

11

Func on

11

Pre requ s es

11

Sk s and know edge

11

Inte gence Support Off cer (ISO)

12

Func on

12

Pre requ s es

12

Sk s and know edge

12

Co ect ons (FIO/IO)

12

Pre requ s es

12

Sk s and know edge

12

Mentors

13

Initial phase

14

Ongo ng nte gence process

14

Post nvest gat on

15

Products

16

Genera pr nc p es

16

Chart ng and nte gence products

16

Sequence of even s and me ne char s

17

Ne work ana ys s

17

Compara ve case ana ys s

17

Commod y f ow char

17

Te ecommun ca ons ana ys s

17

Mapp ng

17

Subjec prof e

17

Cr m na bus ness prof e

17

Informa on repor

17

In e gence repor

17

Secur ty of product

17

C ass f ca ons

17

Phys ca s orage ransm ss on and des ruc on of In e gence produc s and char s

18

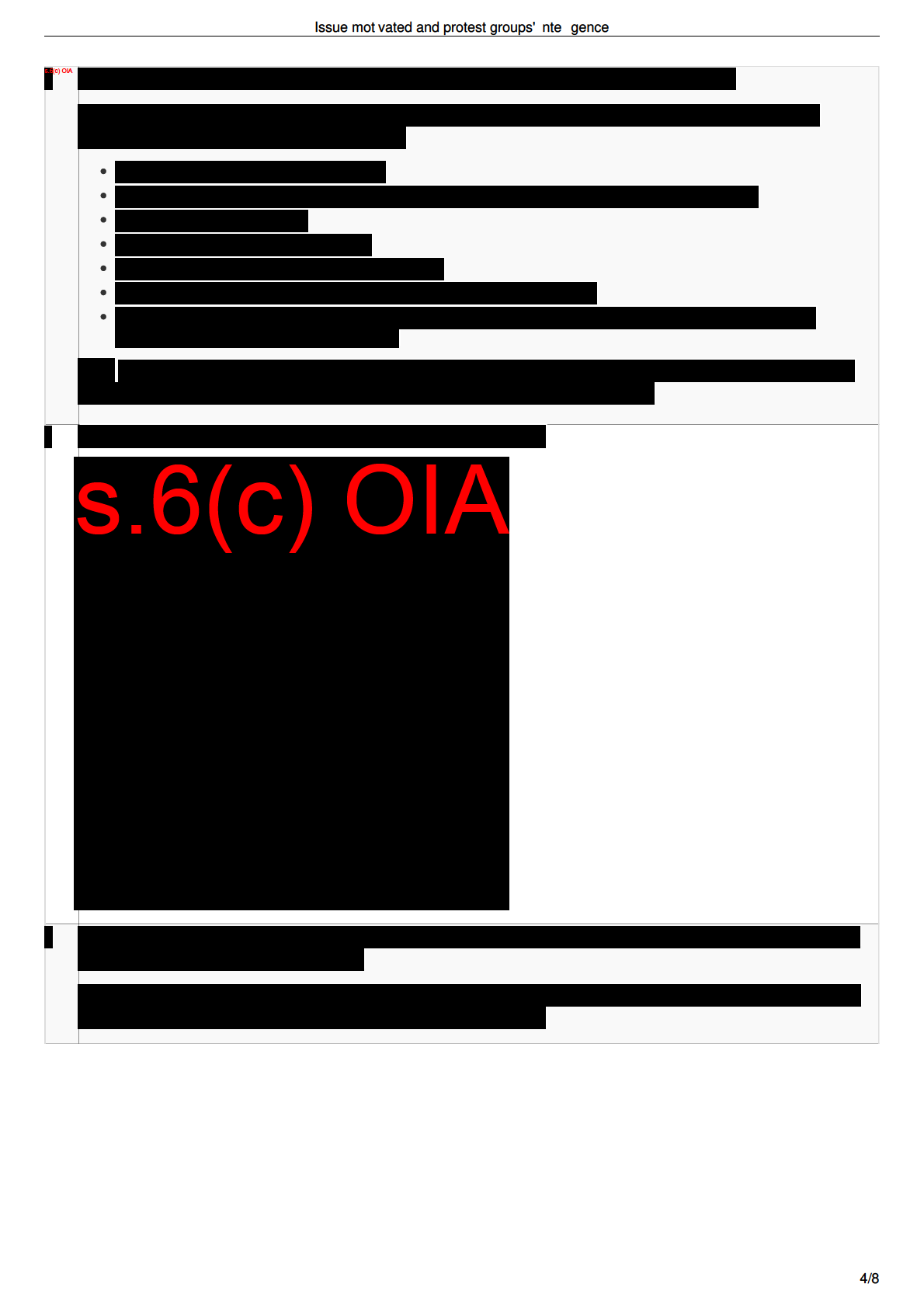

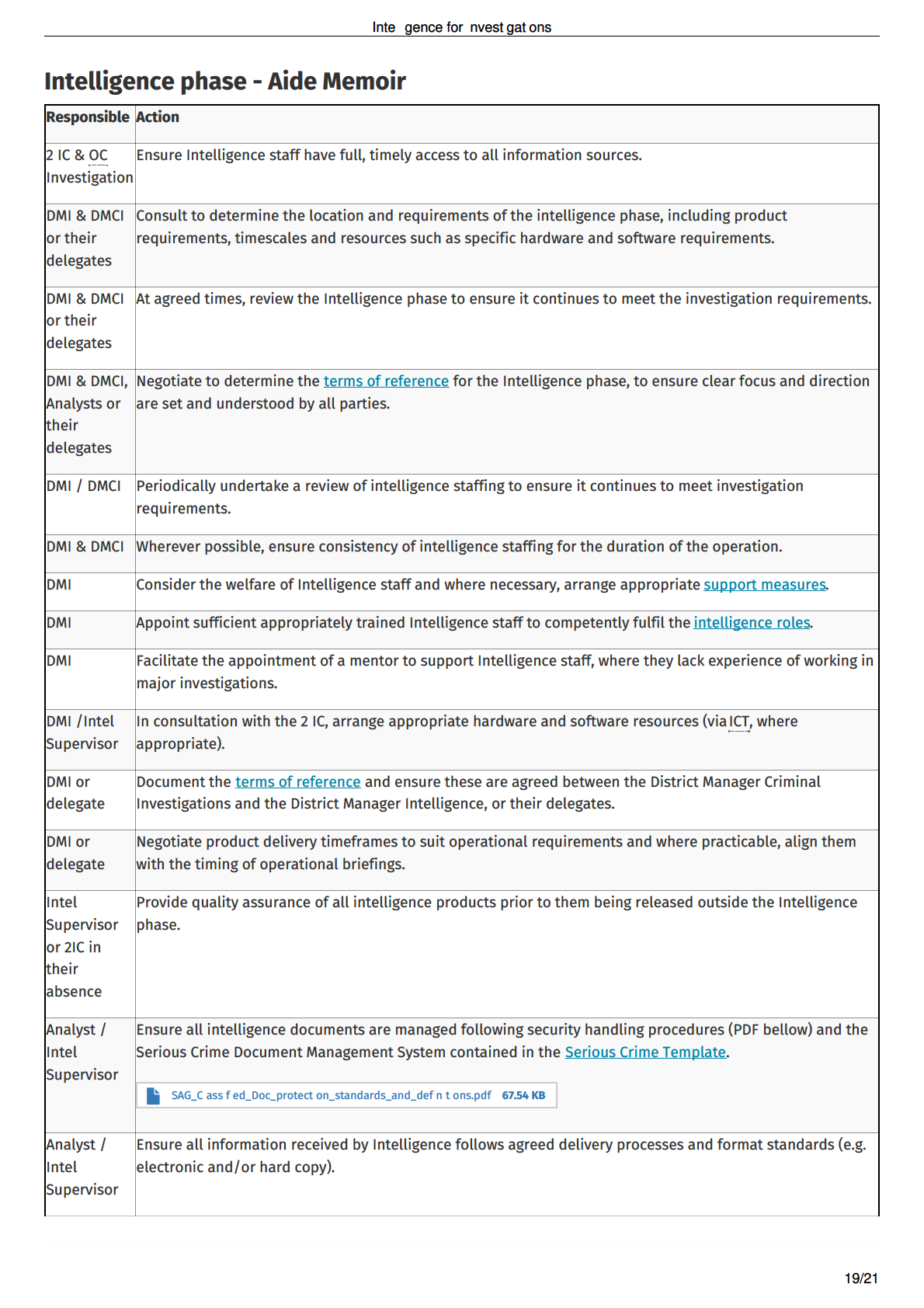

Intelligence phase - Aide Memoir

19

Glossary

21

Inte gence for nvest gat ons

Executive summary

The I4I intelligence process is designed to support and inform investigations with the provision of timely, accurate and

actionable intelligence products that are responsive to the needs of the investigation.

Key, critical points for staff to note:

The use of analytical support from Intelligence is essential in the planning of any major, serious or organised criminal

investigation.

The District Manager Intelligence, in consultation with the District Manager Criminal Investigations or their delegates,

will determine the staffing requirements and physical location of the Intelligence phase.

In all time critical investigations (e.g. homicide, kidnapping etc), Intelligence staff must be capable of working to

demanding timelines in a high pressure environment.

4/21

Inte gence for nvest gat ons

Overview

This section contains the following topics:

Purpose

Value

Intelligence as a phase

Roles and responsibilities

Chain of command

The use of analytical support from Intelligence is essential in the planning of any major, serious or organised criminal

investigation.

The 'Intelligence' chapter provides a common framework for agreed standards, rules, procedures and guidelines for

Intelligence. This part of the chapter provides direction to the intelligence phase of major, serious and organised crime

investigations, hereafter referred to as 'investigations'.

The District Manager Intelligence or delegate will consider requirements in consultation with the District Manager Criminal

Investigations and allocate intelligence staff and resources at the earliest stage possible and throughout the investigation

as appropriate. This will ensure intelligence products that are provided to investigations, are the result of appropriate and

effective collection, collation, management and interpretation of information.

Purpose

The principle function of intelligence is to provide analysis to inform and influence decision makers, who in turn provide

direction to the ongoing investigation process. Intelligence staff are important to this process and ensure decision makers

at all levels are aware of facts, assessments and knowledge gaps.

The intelligence cycle is an ongoing process which ensures every new piece of information available to the investigation, is

assessed with rigour to determine its significance or relevance to tdraw conclusions in order to influence decision makers.

Value

If the intelligence phase is implemented at an early stage of an investigation, then supported by analytical insight

operational decisions can be made regarding intelligence gaps, target identification and the effective deployment of

resources.

Intelligence can:

Analyse information to inform decision makers of opportunities to maximise the use of existing or limited resources.

Focus intelligence gathering through identifying intelligence gaps.

Prioritise lines of enquiry.

Provide a projection of likely future criminal activity.

Assist in the disruption of further crime and incidents (criminal activity).

Promote intelligence into mainstream policing.

Identify associated offenders, offending, trends and new lines of enquiry.

Intelligence as a phase

Within investigations, Intelligence is a professional discipline in its own right. In order to perform effectively, Intelligence is

subject to robust processes, with clearly defined functions and deliverables.

Roles and responsibilities

The investigations (I4I) processes are designed to enhance the structure and capability of the intelligence phases in

investigations.