Lead Coordination Minister for the Government’s Response to the Royal Commission’s Report into the Terrorist Attack on the Christchurch Mosques

9 September 2021

Matthew Hooton

By email:

[FYI request #16400 email]

Ref:

ALOIA081

Dear Matthew

Response to your request for official information Thank you for your request under the Official Information Act 1982 (the Act) on 13 August

2021 for:

“the Briefing Note from the Ministry of Health dated 9 November 2020 referred to in

your letter to me of 2 August 2021. For your convenience, your letter of 2 August

2021 can be found at

https://scanmail.trustwave.com/?c=15517&d=0ZuZ4aM5ju1zc8GPXoF1ZKk60N7e-

koacEMbsJHaZA&u=https%3a%2f%2ffyi%2eorg%2enz%2frequest%2f15865%2fres

ponse%2f61183%2fattach%2f8%2fResponse%2520Letter%2520ALOIA057%2epdf”

The document you have requested is attached as Appendix 1 with some information

withheld under the following sections of the Act:

9(2)(a) to protect the privacy of natural persons

9(2)(f)(iv) to maintain the constitutional conventions that protect the confidentiality of

advice tendered by Ministers and officials.

I trust this information fulfils your request. Under section 28(3) of the Act, you have the right

to ask the Ombudsman to review any decisions made under this request. The Ombudsman

may be contacted by email at: [email address] or by calling 0800 802 602.

Yours sincerely

Hon Andrew Little

Minister of Health

Appendix 1

Briefing

Overview of work to transform New Zealand’s approach to mental

wellbeing

Date due to MO: 9 November 2020

Action required by:

N/A

Security level:

IN CONFIDENCE

Health Report number: 20201961 1982

To:

Hon Andrew Little, Minister of Health

Act

Contact for telephone discussion

Name

Position

Telephone

Information

Toni Gutschlag

Acting Deputy Director General, Mental

s 9(2)(a)

Health and Addiction

Kiri Richards

Group Manager, Mental Healt

Official h and

s 9(2)(a)

Addiction Strategy and Policy

the

under

Minister’s office to complete:

☐ Approved

☐ Decline

☐ Noted

☐ Needs change

☐ Seen

☐ Overtaken by events

Released

☐ See Minister’s Notes

☐ Withdrawn

Appendix 1

Overview of work to transform New

Zealand’s approach to mental wellbeing

Security level:

IN CONFIDENCE

Date:

9 November 2020

To:

Hon Andrew Little, Minister of Health

Purpose of report

1.

This report responds to your request for an overview of the implementation of the

1982

Government’s response to

He Ara Oranga: Report of the Government Inquiry into Mental

Health and Addiction (

He Ara Oranga). It also provides you with a summary of wider

Act

mental health and addiction work and your ministerial responsibilities under the Mental

Health (Compulsory Assessment and Treatment) Act 1992.

Summary

2.

Mental wellbeing impacts the lives of all people in New Zealand. Supporting people to

have good mental wellbeing is more important now than ever, given the wide-ranging

Information

impacts of COVID-19.

3.

A large programme of work is underway to implement the response to

He Ara Oranga.

He Ara Oranga called for the transformation of our approach to mental health and

addiction, underpinned by achieving equity and a collaborative approach with

Official

communities.

4.

This Government’s response to

He Ara Oranga is supported by the delivery of the

the

Budget 2019 investment of $1.9 billion in a cross-government mental wellbeing package.

A key focus of the Budget 2019 investment is the initiative to expand access and choice

of primary mental health and addiction support nationally ($455 million over four years).

under

This initiative is rolling out new services over five years, including in general practices

and kaupapa Māori, Pacific and youth settings.

5.

The Ministry of Health (the Ministry) is also leading the psychosocial response to COVID-

19, including the development of

Kia Kaha, Kia Māia, Kia Ora Aotearoa: Psychosocial and

Mental Wellbeing Plan (Kia Kaha).

Kia Kaha is a cross-sectoral plan that outlines a

national mental wellbeing framework to guide collective efforts to support mental

Released

wellbeing and sets out priority actions over the next 12–18 months.

6.

The development of a longer-term pathway to transform our approach to mental health

and addiction will build on

Kia Kaha and will outline the direction for our approach to

mental health and addiction over the next 10 years. The pathway will guide the actions

and investment needed to achieve the transformative change called for in

He Ara

Oranga.

7.

Alongside current work, the Ministry has also started planning for progressing Labour’s

manifesto commitments. These align strongly with the direction set by the Government’s

response to

He Ara Oranga and recent investments in mental wellbeing.

Appendix 1

Recommendations

This briefing has no recommendations and is for your noting only.

Toni Gutschlag

Hon Andrew Little

Acting Deputy Director-General

Minister of Health

Mental Health and Addiction

Date:

Date: 9/11/2020

1982

Act

Information

Official

the

under

Released

Appendix 1

Overview of work to transform New

Zealand’s approach to mental wellbeing

Context

1.

Mental wellbeing impacts the lives of all people in New Zealand. Approximately one in

five New Zealanders experience mental illness or addiction each year. Some population

groups are more at risk of poorer outcomes than others, including Māori, Pacific

peoples, younger people and people experiencing financial hardship.

2.

Mental wellbeing is not simply an absence of mental illness or addiction. It is a state of

wellbeing where people feel positive and are able to adapt and cope with life s

challenges. It is fostered in our homes, schools and communities and is influenced by

1982

wider determinants such as income, employment, housing, education, and freedom from

abuse, violence and discrimination.

Act

3.

The health and disability system plays a key role in supporting mental wellbeing through

the provision of a continuum of mental health and addiction supports to respond to

different levels of need. This ranges from wellbeing promotion activities; to primary and

community supports; to specialist services for those with higher needs, including crisis

responses and forensic services for people interacting with the justice system.

4.

Appendix One provides more information about New Zealanders’ mental wellbeing

Information

needs, outcomes and inequities, and the mental health and addiction system.

5.

COVID-19 has also had an impact on people’s mental wellbeing, including creating

heightened levels of distress, anxiety and a sense of ongoing uncertainty. This is a

normal response to such an event. Work to suppo

Official rt people’s mental wellbeing, and to

respond to people’s mental health and addiction needs, is therefore particularly

important now as it will help with both the immediate recovery from COVID-19 and will

the

lay the foundation for positive mental wellbeing in the longer term.

Inquiry into Mental Health and Addiction

under

6.

An independent Government Inquiry into Mental Health and Addiction was established

in 2018 to hear from people in New Zealand about the changes needed to address

mental health and addiction issues. Addressing inequities in outcomes was one of the

key drivers for the Inquiry.

7.

The Inquiry report –

He Ara Oranga – was presented to the then Government in

Released

November 2018 with 40 recommendations. Key shifts called for include:

a. ensuring our approach works for and meets the needs of Māori

b. moving to a holistic, whole-of-government approach grounded in wellbeing that

recognises the social, cultural and economic foundations of mental wellbeing and

looks across the life course

c. increasing access to and choice of mental wellbeing supports to ensure all people in

New Zealand receive the support they need, when and where they need it

d. designing supports collaboratively with communities, Māori and people with lived

experience of mental health and addiction issues.

Appendix 1

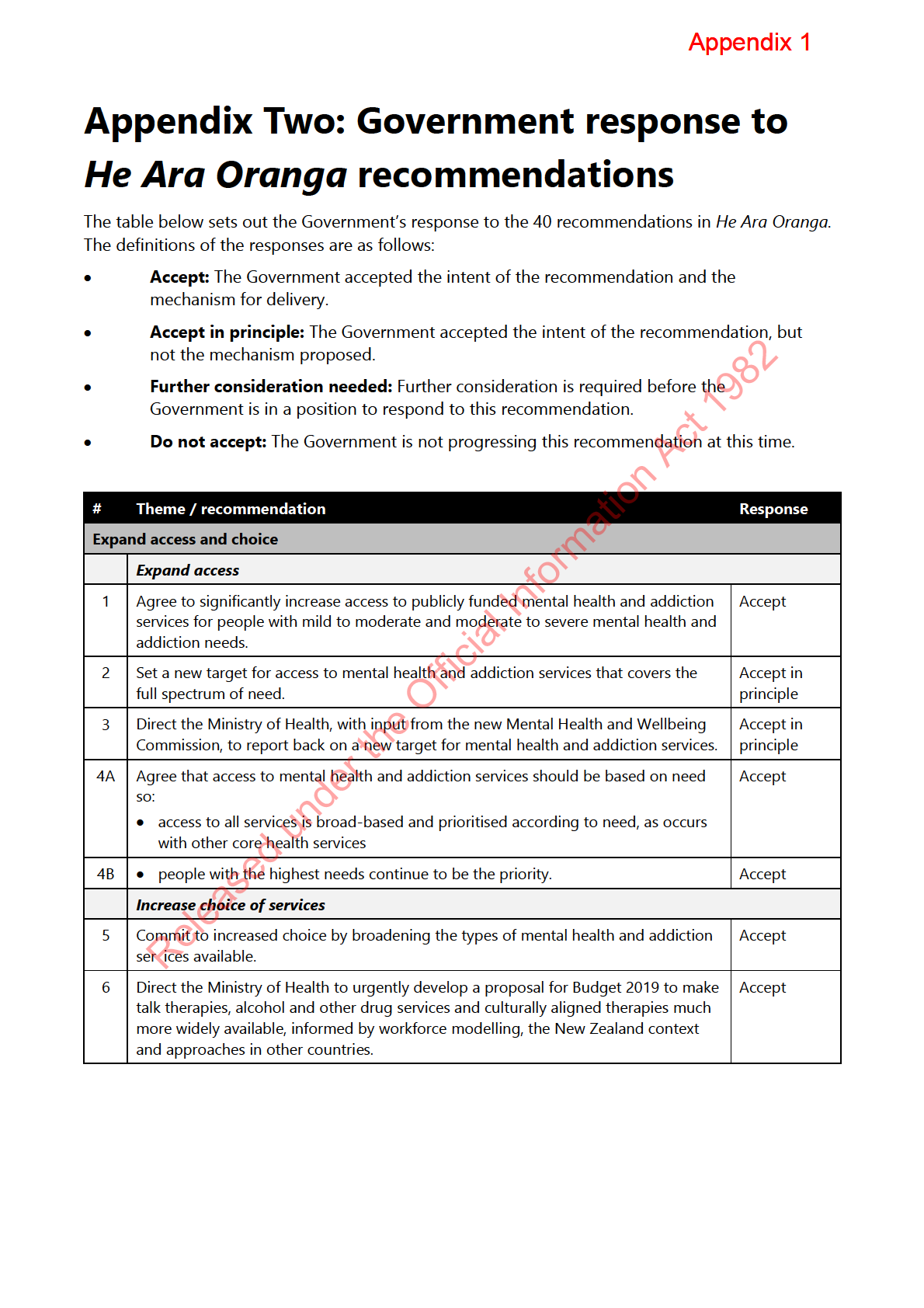

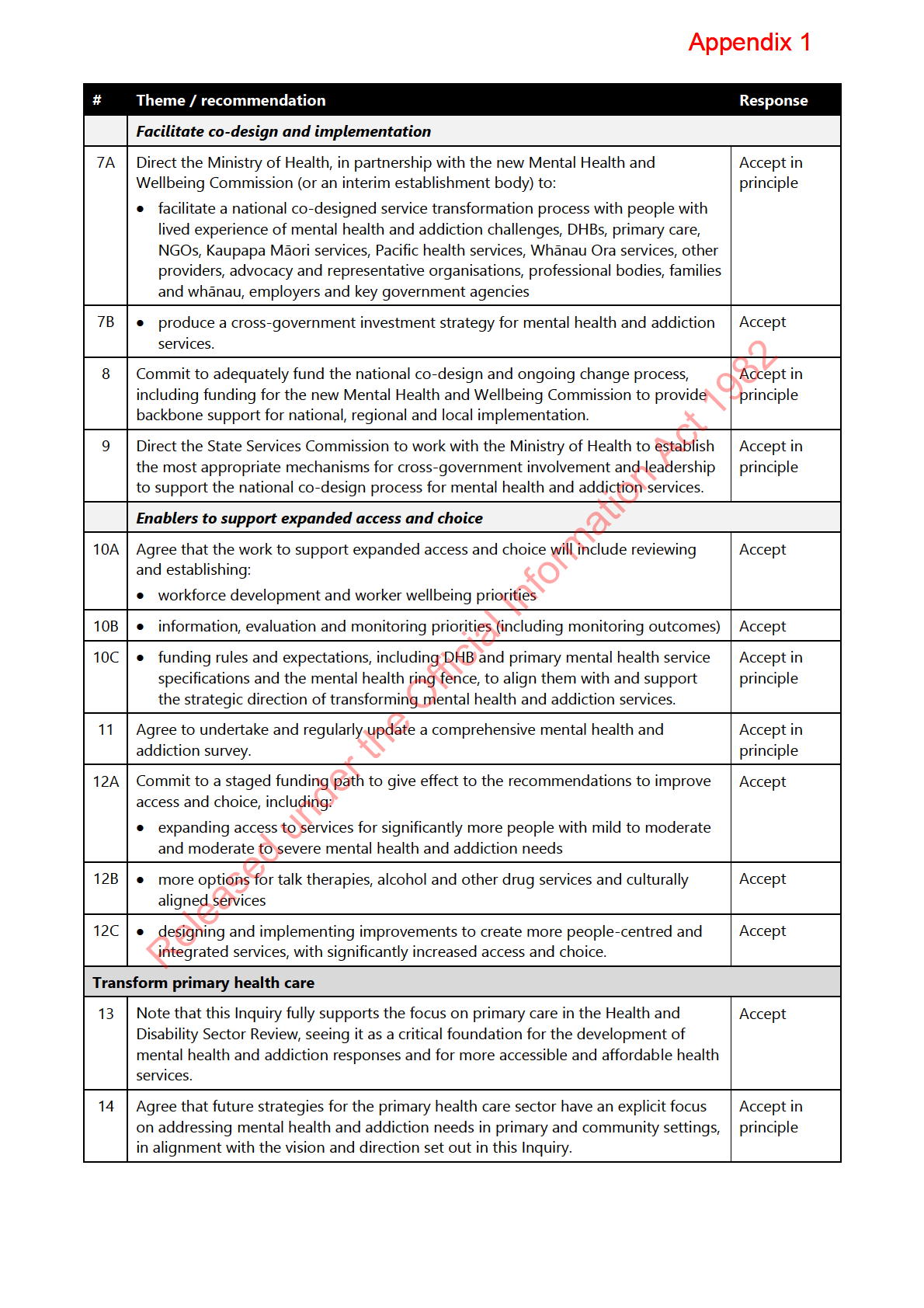

8.

The then Government formally responded to

He Ara Oranga in May 2019,

accepting,

accepting in principle, or agreeing to further consider 38 of the 40 recommendations

[CAB-19-MIN-0182 refers].

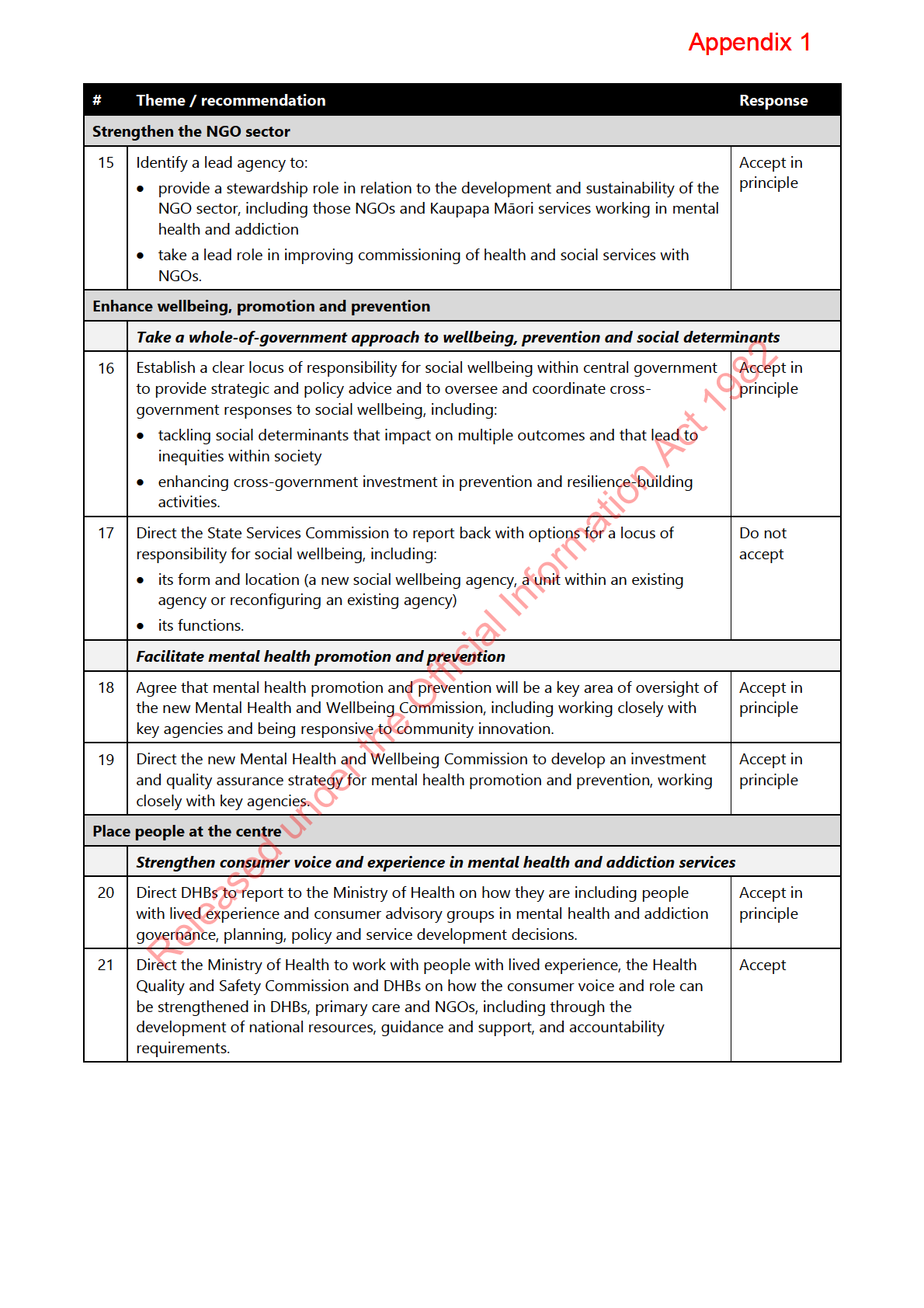

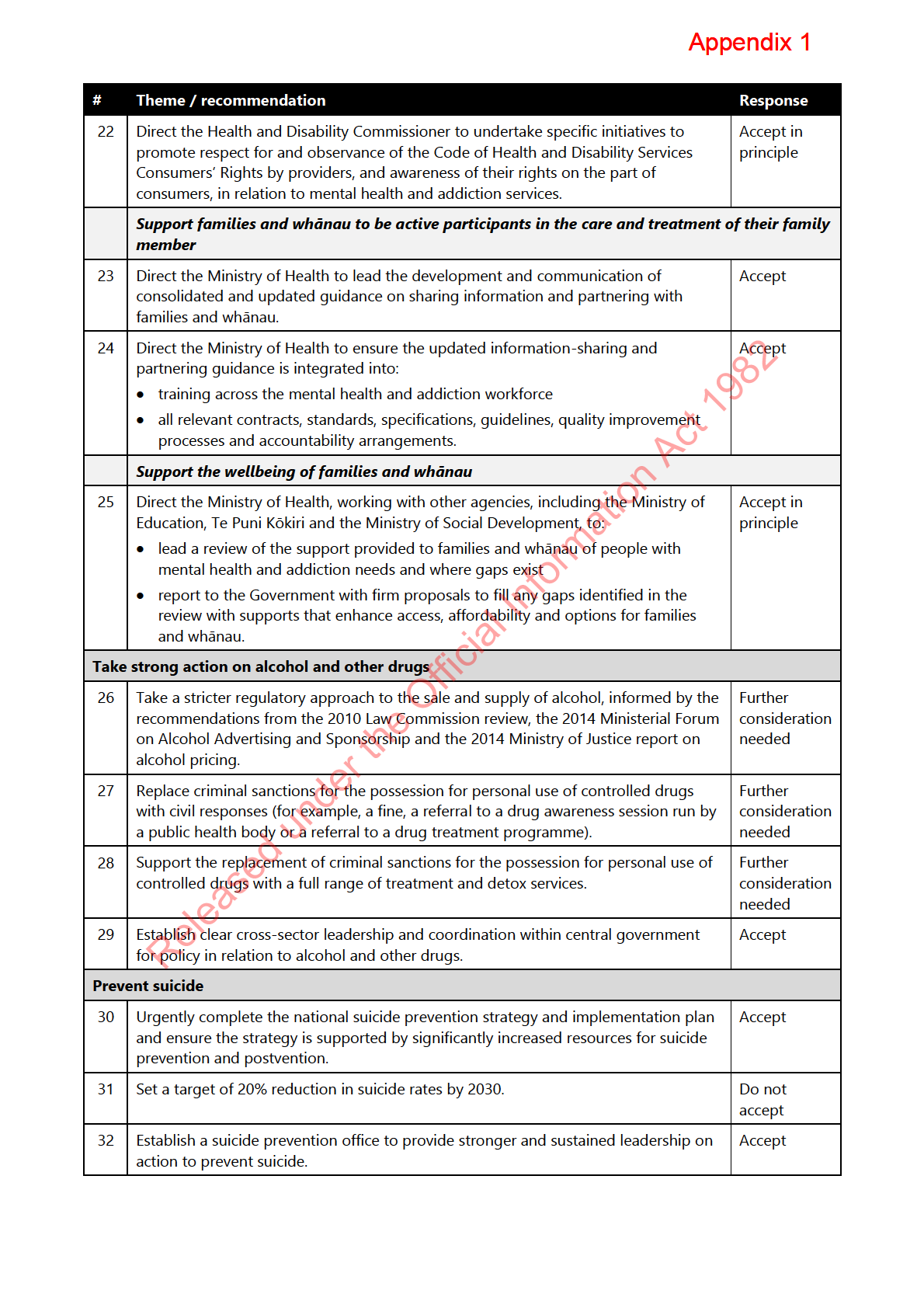

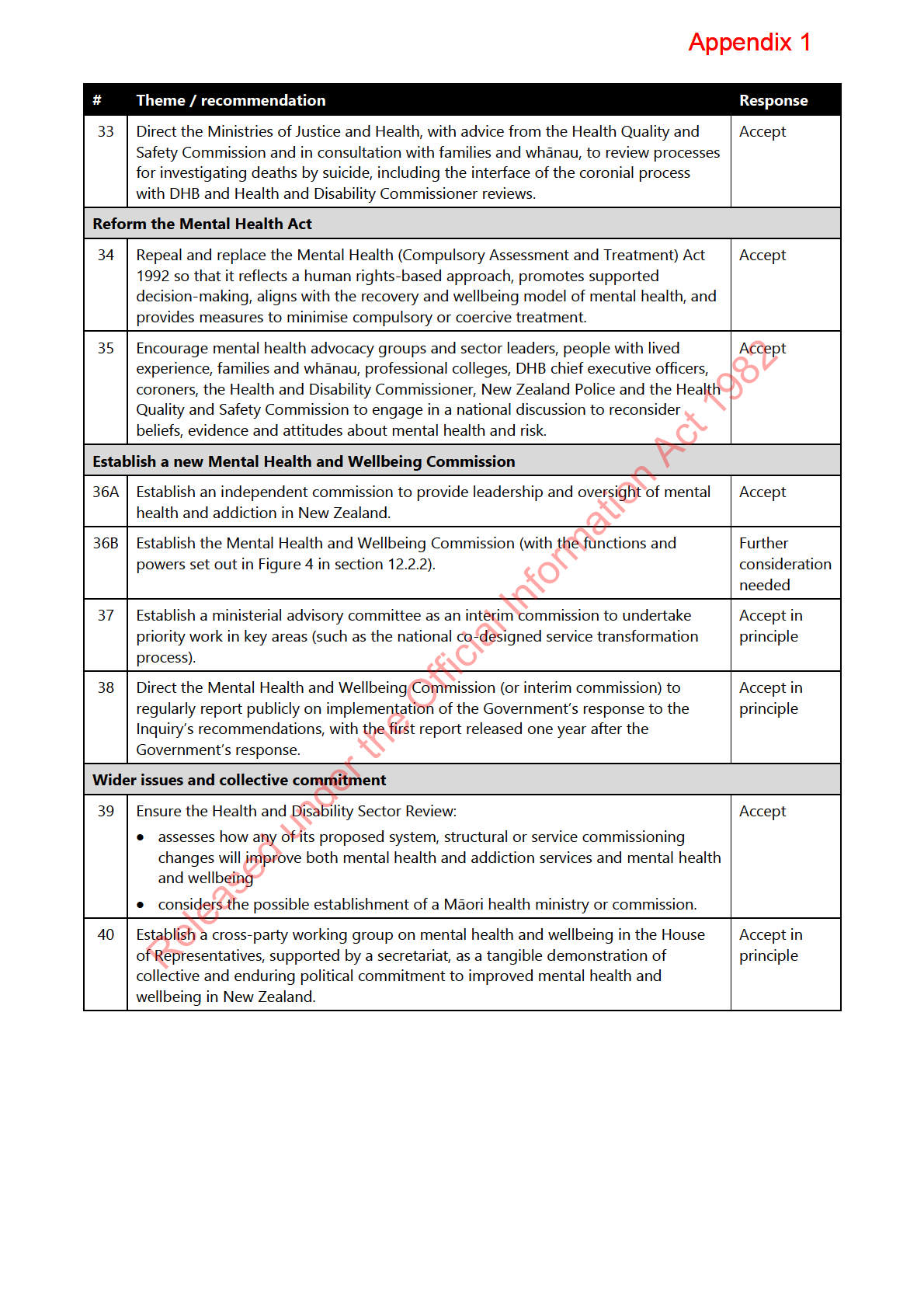

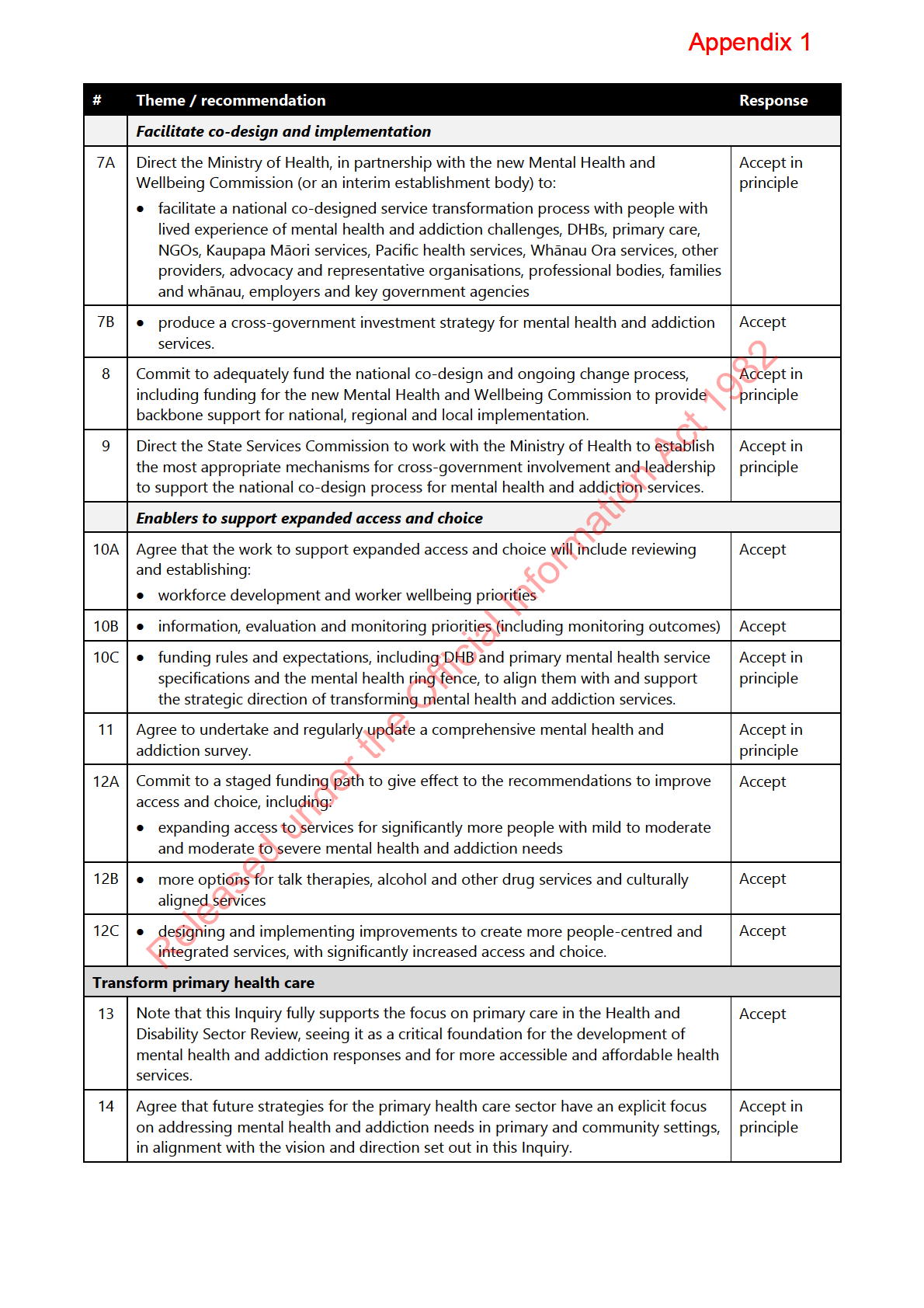

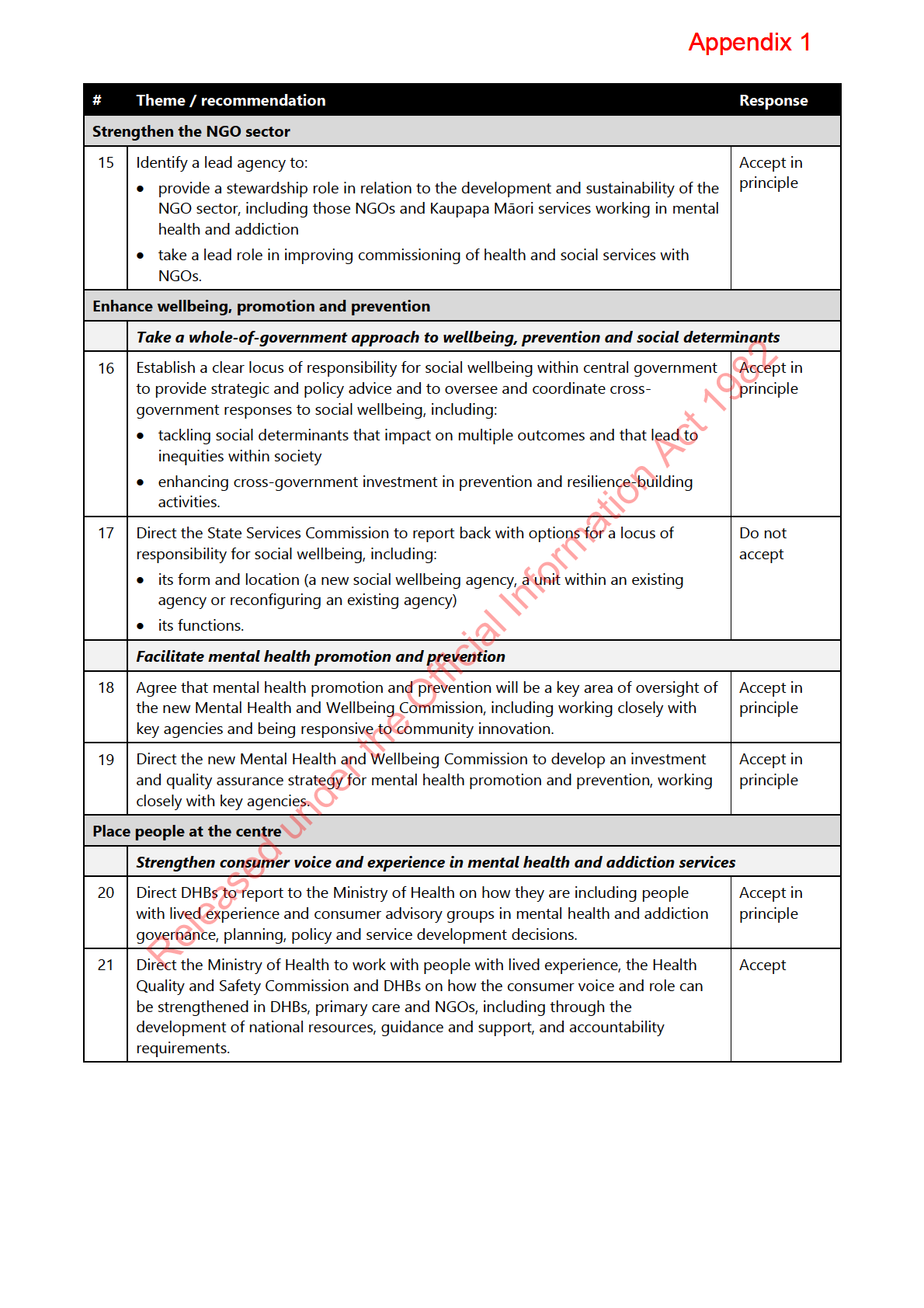

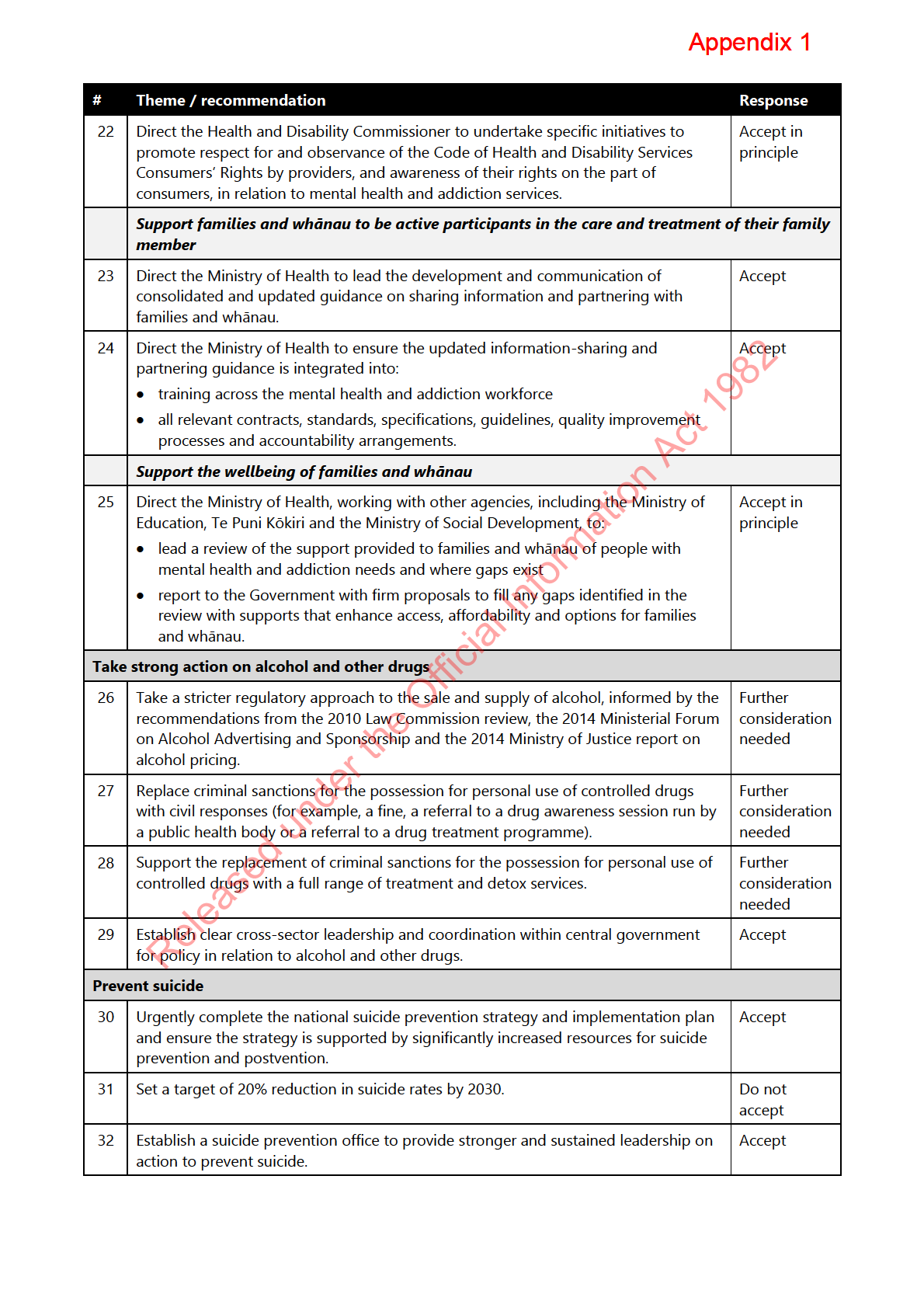

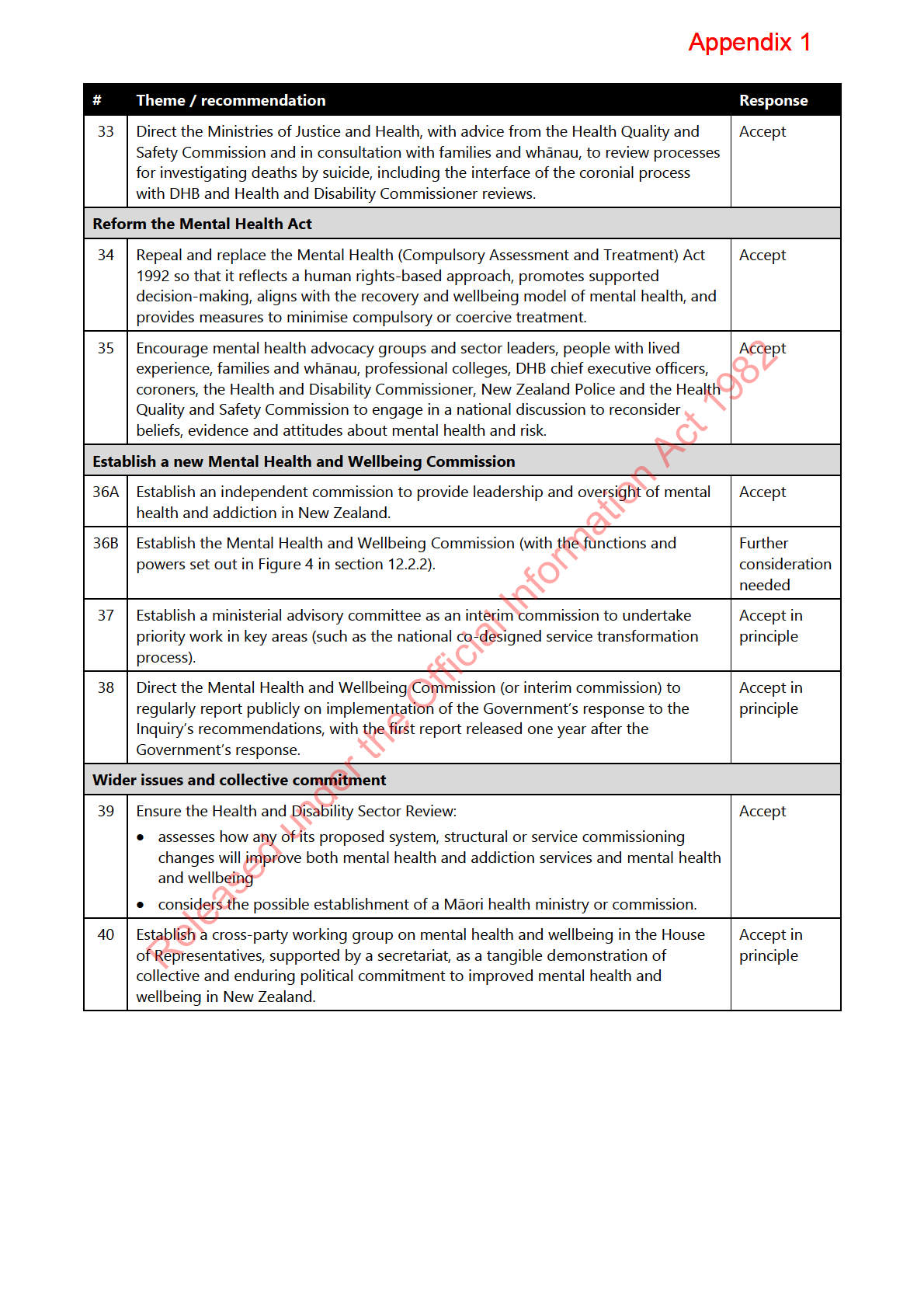

Appendix Two sets out the Government’s response to the

recommendations.

Implementing the Government’s response to He Ara Oranga

9.

Delivering on the Government’s response to

He Ara Oranga requires substantive system

shifts, actions and investment that will need to be prioritised and sequenced over the

short, medium and longer term. For this reason, the Ministry of Health’s (the Ministry’s)

mental health and addiction work programme is guided by the Government’s response

to

He Ara Oranga but has a focus on transforming the approach to mental health and

addiction that is broader than solely implementing the recommendations

.

10.

Operational matters such as oversight and administration of mental health and

addiction-related legislation, and work to support and monitor delivery of mental healt

1982 h

and addiction services, are also part of our work programme.

Act

A focus on achieving equity

11.

He Ara Oranga highlighted that there are significant inequities and unmet needs,

particularly for Māori, as well as for other population groups such as young people,

Pacific peoples, rainbow communities, disabled people, rural communities and people

interacting with the justice system. Further information about existing inequities is

included in

Appendix One.

Information

12.

Achieving equity underpins the Ministry’s mental health and addiction work. The

Ministry is beginning to address inequities through activities such as:

a. providing targeted funding for Māori and for population groups that experience

Official

inequitable mental health and addiction outcomes

b. collaboratively designing services with communities, and adopting new and

the

innovative procurement processes to support a broader range of kaupapa Māori,

Pacific and community providers to participate

c. expanding services in primary and community settings for people with mild to

under

moderate needs, who have historically had limited options for support

d. supporting increased access to services by Māori to reflect the fact that Māori have

higher rates of prevalence of mental health and addiction issues

e. improving the current application of the Mental Health (Compulsory Assessment

and Treatment) Act 1992 (the Mental Health Act) to reduce the use of compulsory

Released

treatment for Māori, while reforming the Act to embed a human rights approach.

Key areas of work underway

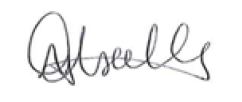

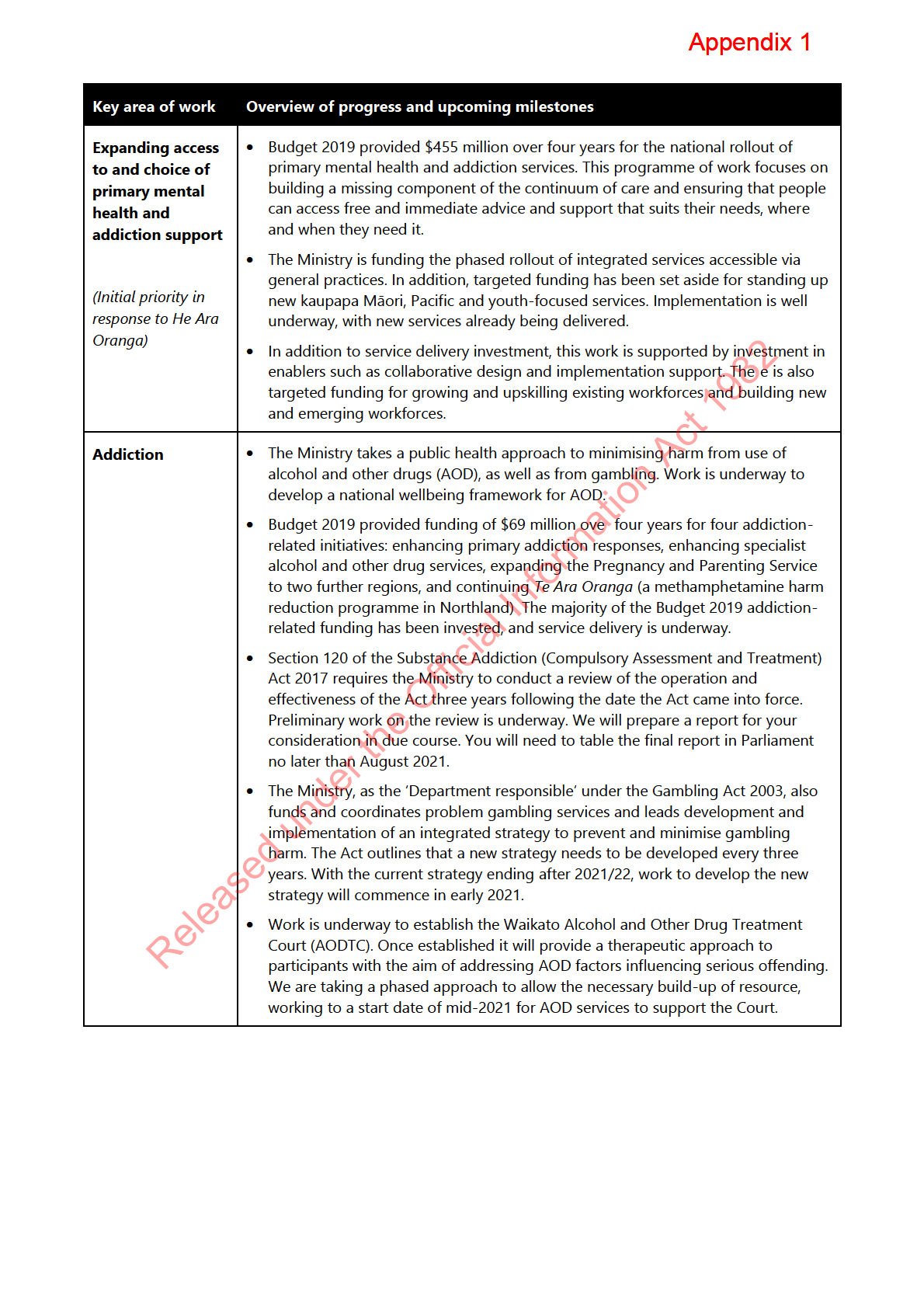

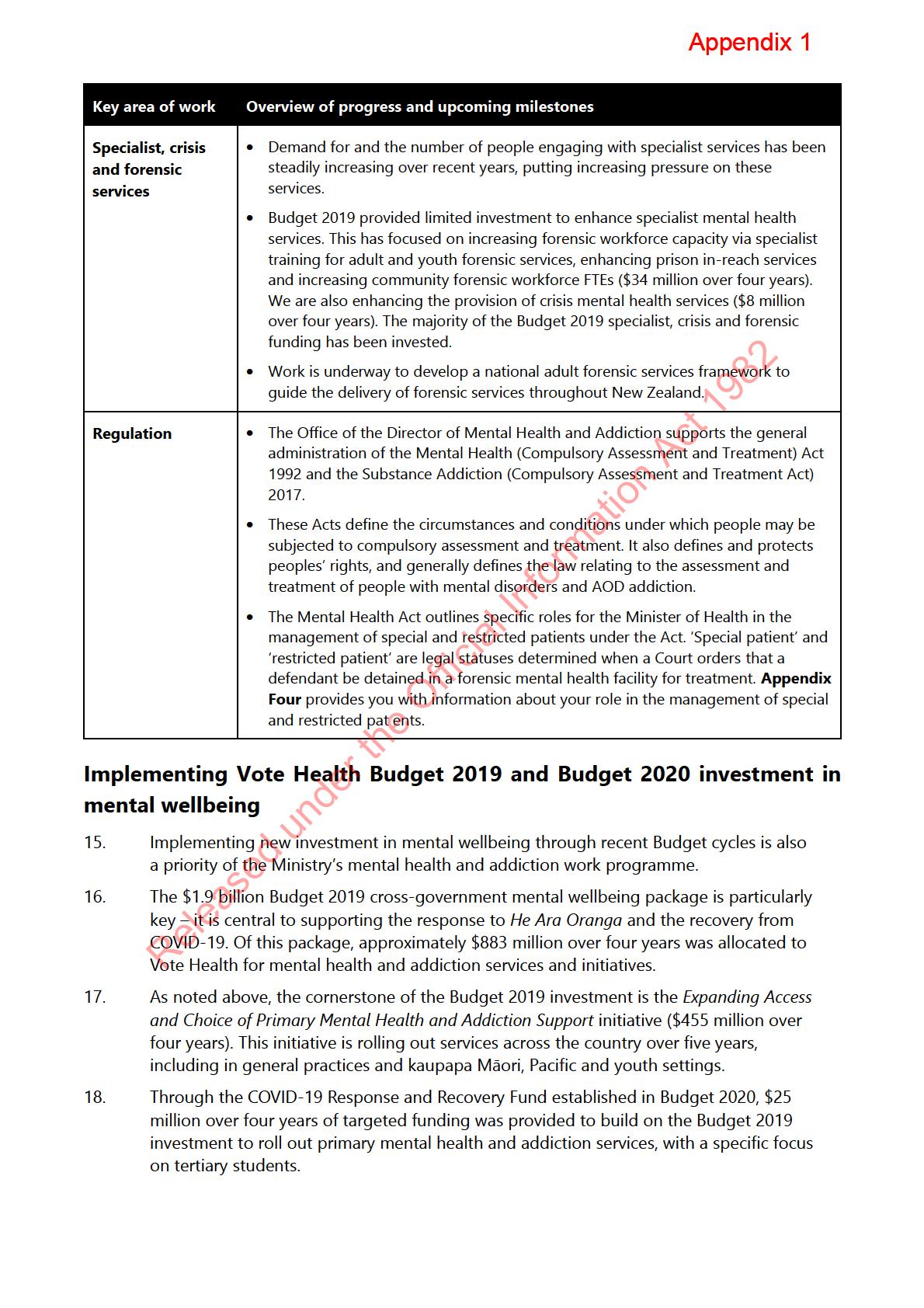

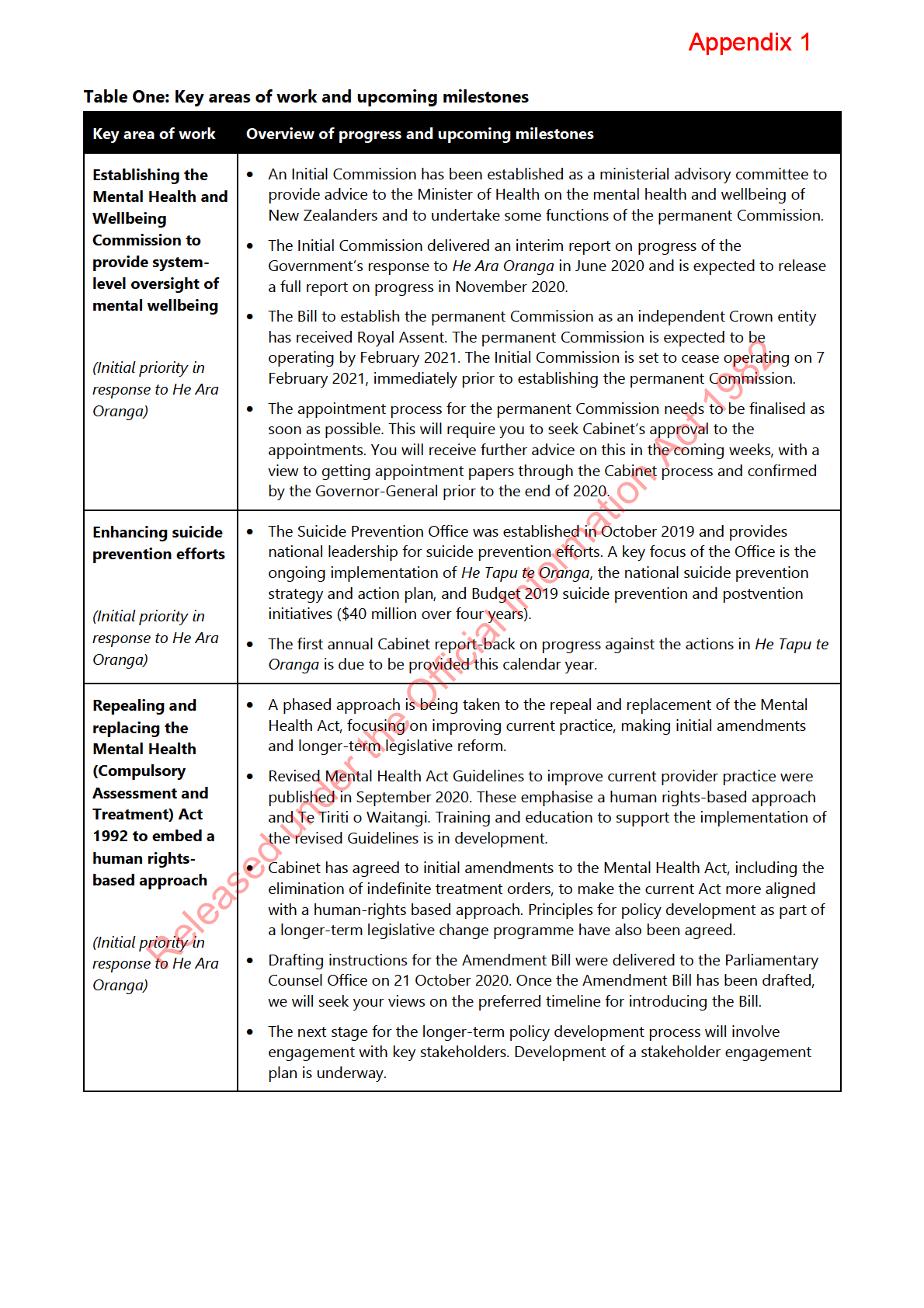

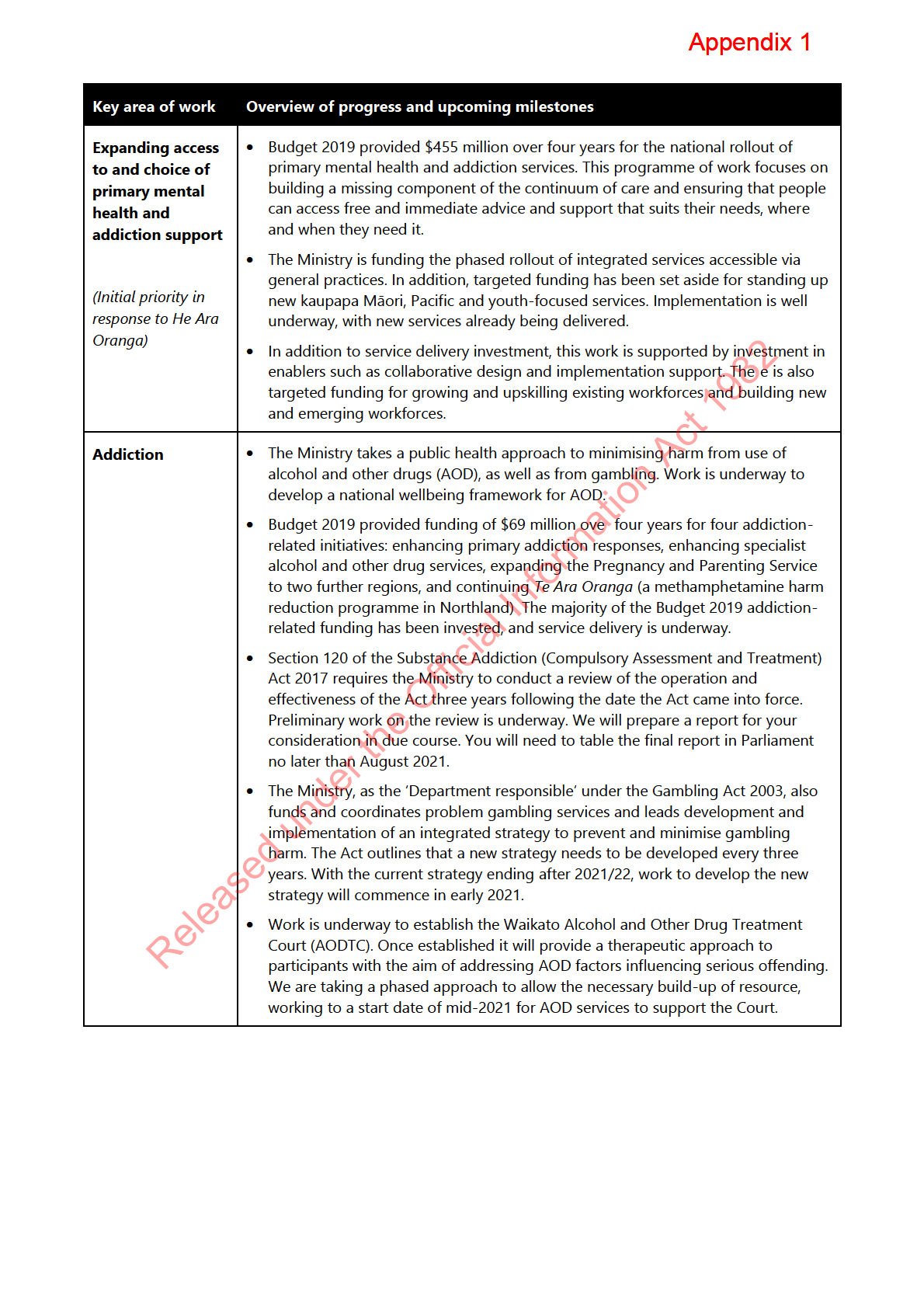

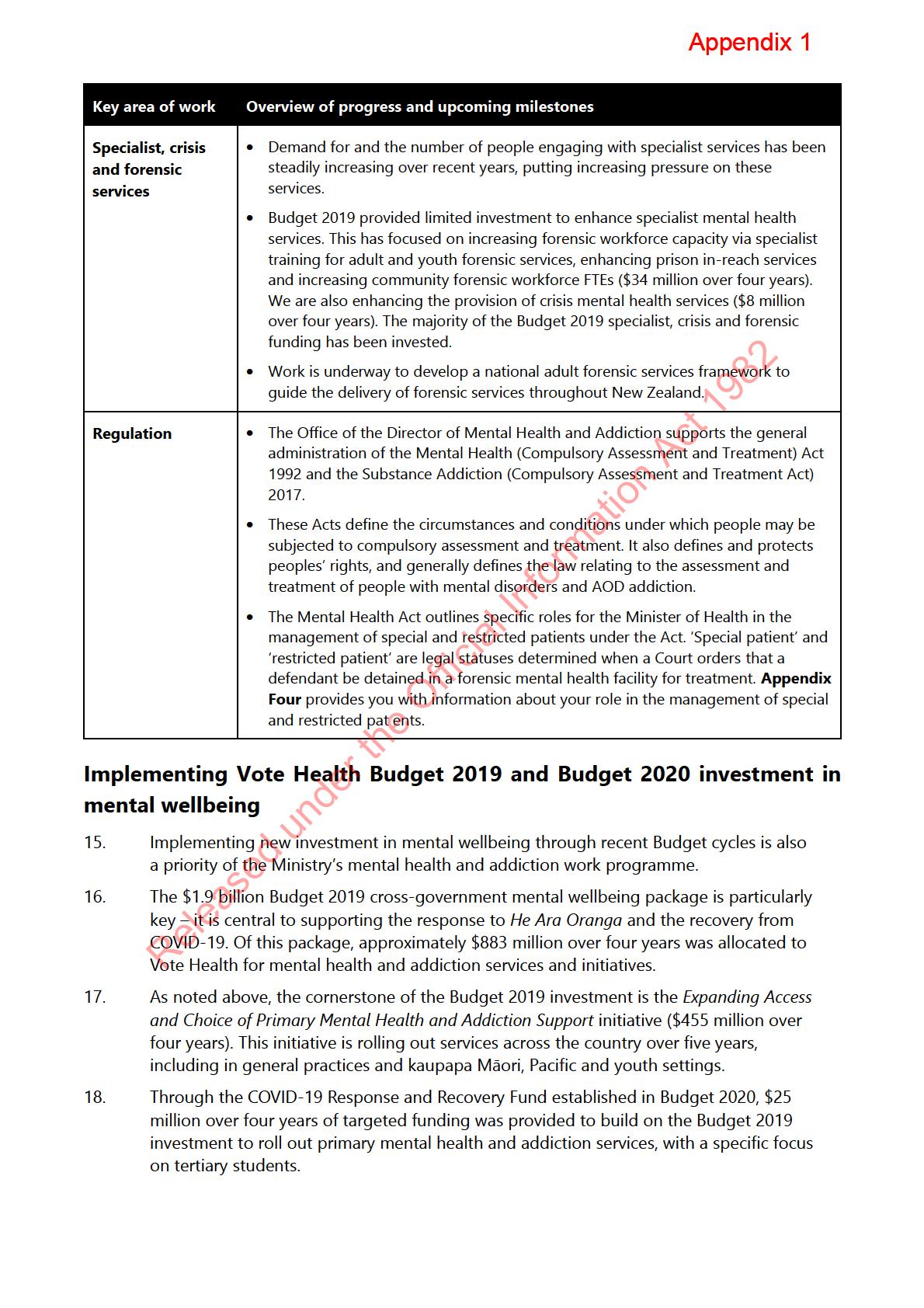

13.

Table One outlines key information about areas of work and upcoming milestones that

are underway to help transform our approach to mental health and addiction. This

includes work related to the initial priorities the then Government identified as part of its

response to

He Ara Oranga, as well as work to respond to specific recommendations in

He Ara Oranga.

14.

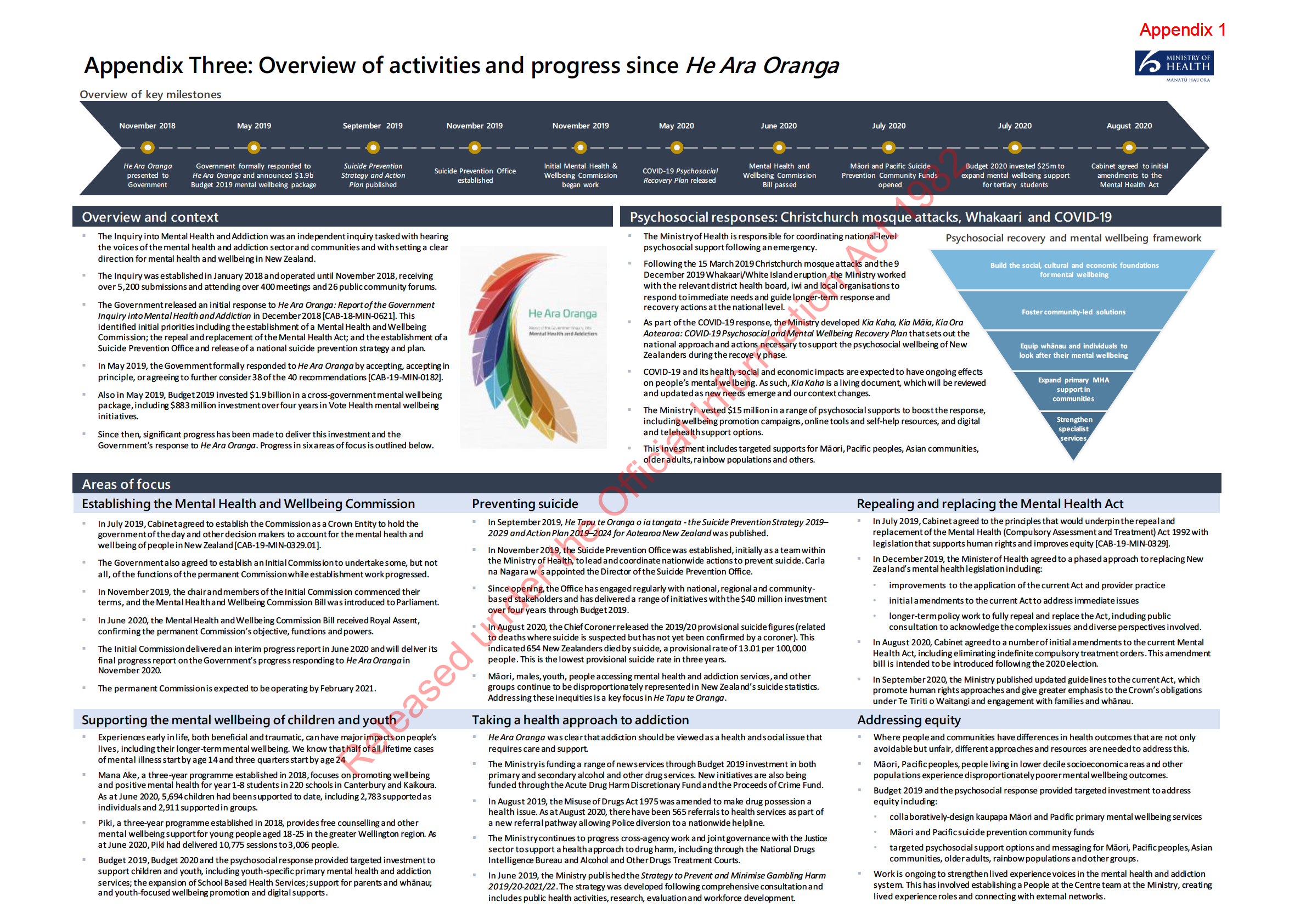

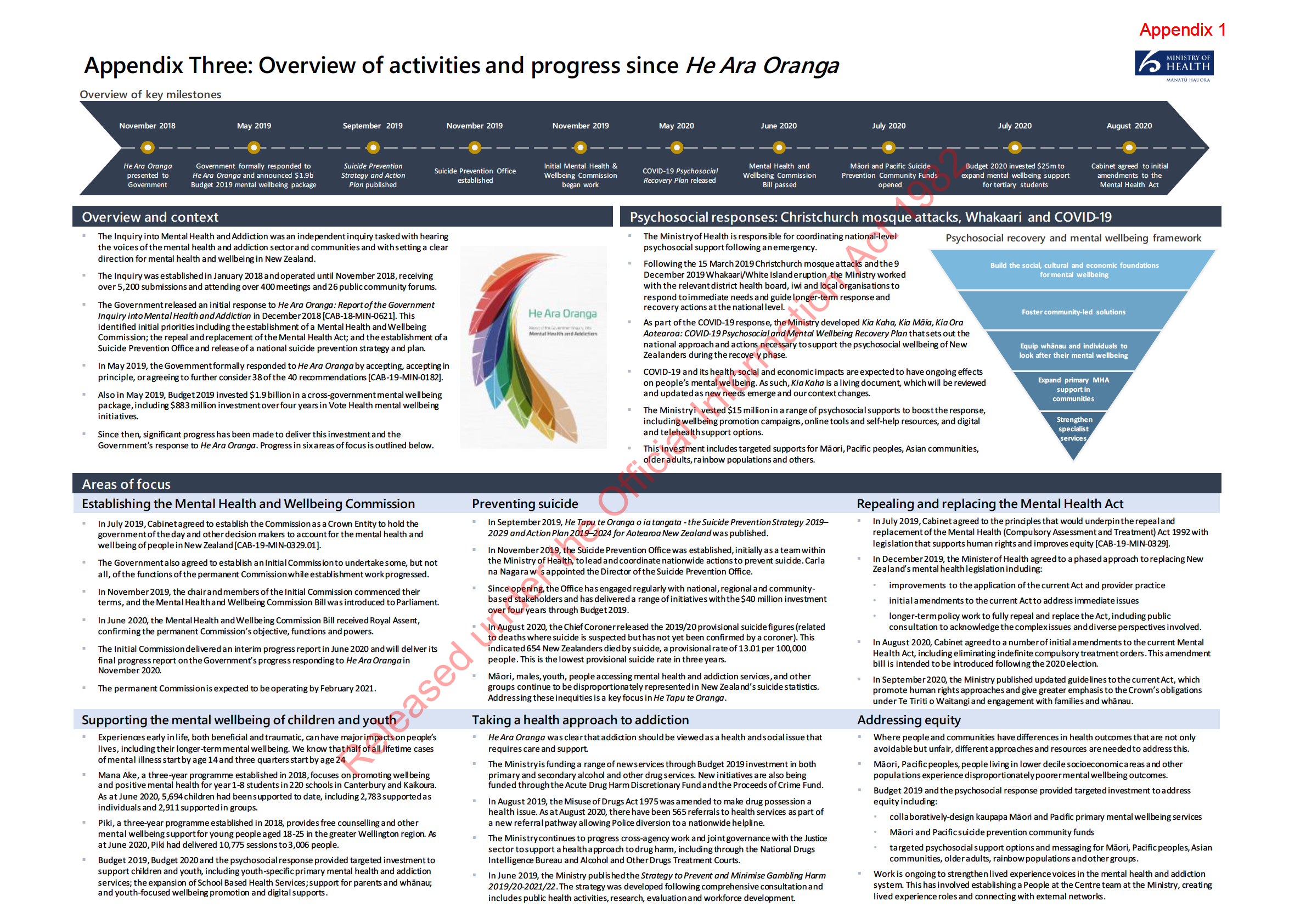

The A3 attached as

Appendix Three provides an overview of progress made since the

Government’s response to

He Ara Oranga.

1982

Act

Information

Official

the

under

Released

1982

Act

Information

Official

the

under

Released

1982

Act

Information

Official

the

under

Released

Appendix 1

19.

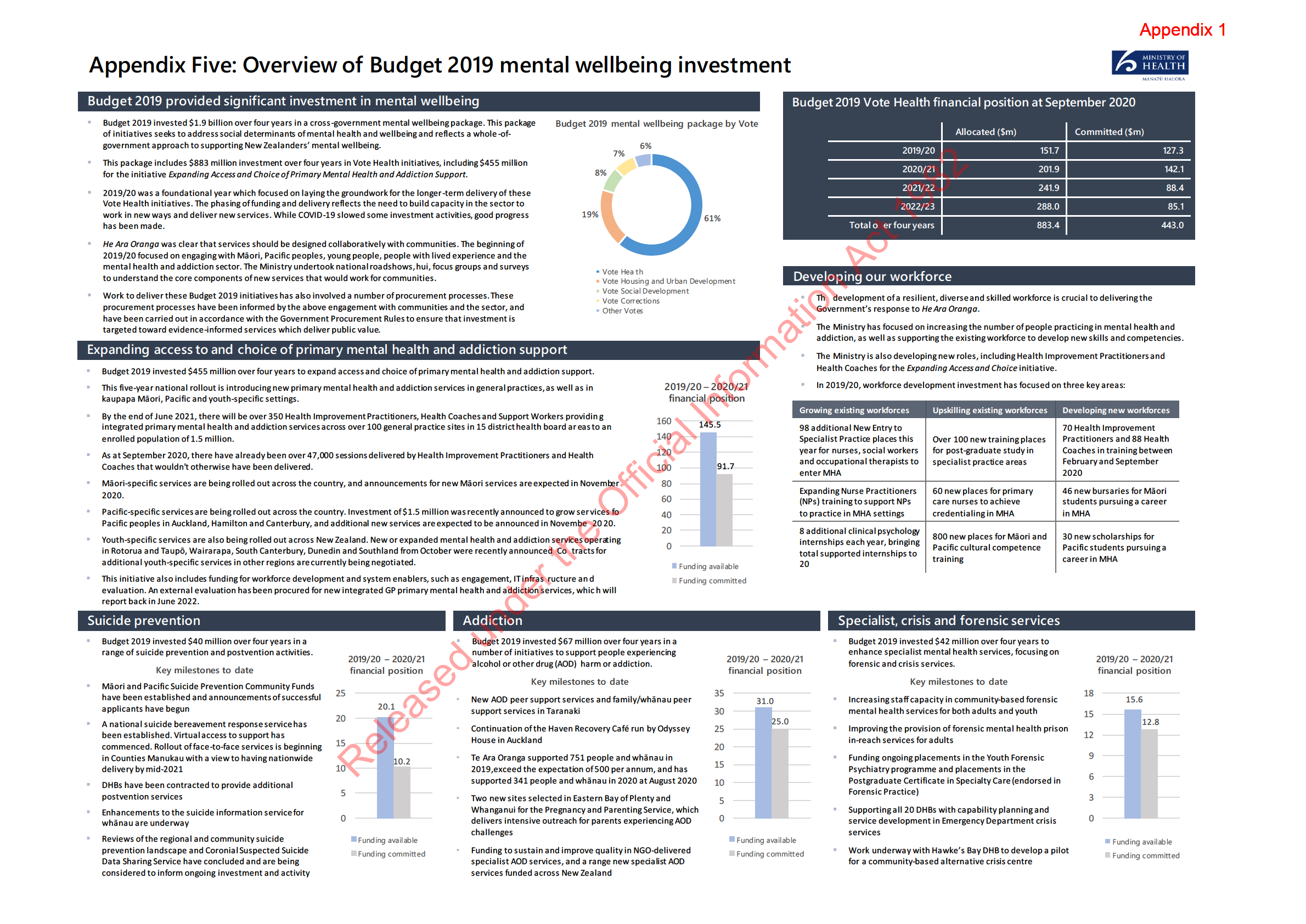

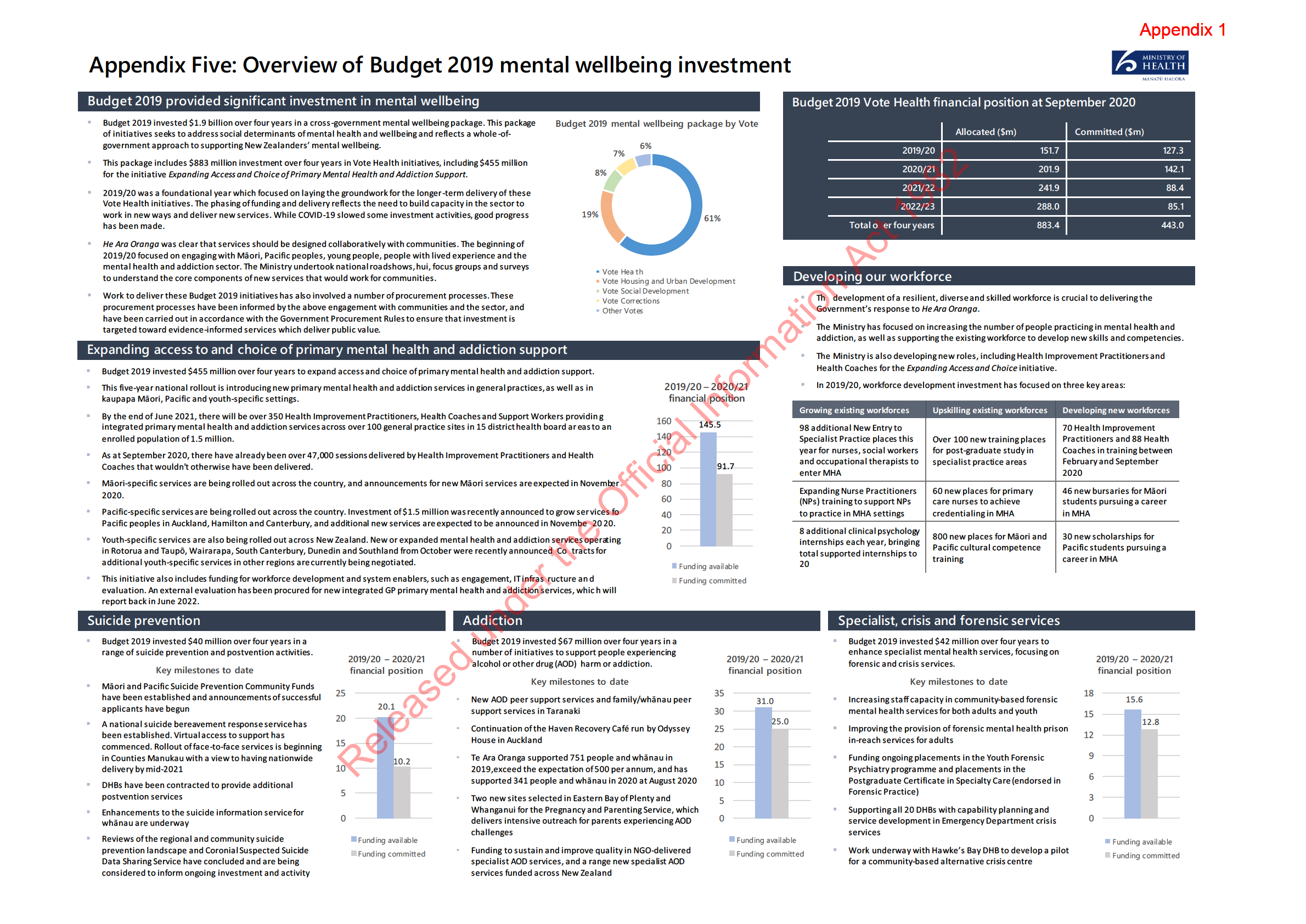

The remainder of Vote Health investment in the Budget 2019 mental wellbeing package

provided top-ups to support work in other areas such as suicide prevention, specialist

addiction treatment, school-based mental wellbeing and forensic mental health services.

20.

Delivery of Budget initiatives is well underway. The A3 attached as

Appendix Five provides an overview of progress made implementing Budget 2019 Vote Health mental

wellbeing investment.

21.

The previous Minister of Health reported monthly to the Cabinet Priorities Committee on

implementation of the Vote Health Budget 2019 mental wellbeing initiatives.

Progressing manifesto commitments

22.

The Ministry is actively planning to implement Labour’s 2020 election manifesto

commitments for new mental health and addiction initiatives once decisions are made

by you and Cabinet, including around new funding. These initiatives complement our

1982

current work programme for implementing the Government’s response to

He Ara

Oranga and recent investments in mental wellbeing

. They align strongly with our focus

Act

on supporting the mental wellbeing of children, young people and their parents and

whānau; taking a health approach to addressing AOD harm; and addressing inequitable

mental wellbeing outcomes.

23.

S9(2)(f)(iv)

Information

24.

Official

the

25.

under

26.

Released

Leading the psychosocial response to COVID-19

27.

The Ministry is leading the psychosocial response to COVID-19, including the

development of

Kia Kaha, Kia Māia, Kia Ora Aotearoa: Psychosocial and Mental

Wellbeing Plan (

Kia Kaha).

Kia Kaha is a cross-sectoral plan that sets out a national

mental wellbeing framework to guide collective efforts across national, regional and

local levels.

Appendix 1

28.

The first version of

Kia Kaha was released in May 2020. An updated version is expected

to be released before the end of the year. The updated version of

Kia Kaha represents

the first phase of a longer-term pathway to implement the response to

He Ara Oranga.

This updated version will include cross-government actions over the next 12–18 months,

including actions as part of the response to

He Ara Oranga.

29.

The Ministry is also implementing the $15 million one-off investment allocated to

support the psychosocial response. This investment has supported wellbeing promotion

campaigns, digital self-help tools, telehealth services and targeted supports for priority

populations such as Māori, Pacific peoples, Asian communities, older adults and rural

communities.

Long-term pathway for transformation

30.

The former Minister of Health was previously invited to report back to Cabinet with a

long-term pathway to transform New Zealand’s approach to mental health and

1982

addiction [CAB-19-MIN-0182 refers]. S9(2)(f)(iv)

Act

31.

The long-term pathway is intended to outline the direction for our approach to mental

health and addiction over the next ten years, and to guide the actions and investment

needed to achieve the transformative change called for in

He Ara Oranga.

32.

The long-term pathway will build on

Kia Kaha but will need to be flexible as work

progresses, including with any relevant changes in response to the Health and Disability

System Review, and as New Zealanders’ needs and aspirations change

Information . It will also need

to reflect ongoing engagement with Māori, people with lived experience of mental

health and addiction issues, whānau and communities.

33.

S9(2)(f)(iv)

Official

. The release

the

of an updated version of

Kia Kaha will help respond to public calls for a clear action plan

to implement

He Ara Oranga in the interim.

34.

Officials can provide you with further advice on next steps for progressing the long-term

pathway to help inform decisions about

under

the Cabinet report-back.

Priority areas for future investment

35.

The Government’s response to

He Ara Oranga acknowledged that multiple years of

significant and sustained effort and investment will be required to transform our

approach to mental

Released health and addiction.

36.

Moreover, while there has been a recent increase in investment in mental health and

addiction services, there is still significant pressure on some parts of the system.

37.

S9(2)(f)(iv)

Appendix 1

c. resource to support the implementation of the initial amendment to the Mental

Health Act to eliminate indefinite treatment orders

s 9(2)(f)(iv)

38.

Officials are able to provide further advice on these areas, as well as any immediate

manifesto commitments that require funding that you wish to progress.

Upcoming ministerial decisions

39.

Over the coming months there are a number of decisions that will likely need to be

sought from you or Cabinet, including the following:

a. appointments for the new Mental Health and Wellbeing Commission 1982

b. S9(2)(f)(iv)

Act

c. timing of and content for the Cabinet report-back on suicide prevention

d. progression of the Bill to implement initial amendments to the Mental Health Act

e. appointments to the Mental Health Review Tribunal and appointment of deputy

district inspectors (refer

Appendix Four for further information)

f. areas for focus of Budget 2021 mental wellbeing bids

Information

g. whether to continue providing monthly updates to the Cabinet Priorities Committee

on progress implementing the Vote Health Budget 2019 mental wellbeing initiatives.

40.

Information about indicative upcoming milestones and matters requiring ministerial or

Cabinet decisions is also outlined in

Appendix Six.

Official

Next steps

the

41.

Officials are available to discuss and can provide further information and advice on the

matters raised in this report.

under

ENDS.

Released

Appendix 1

Appendix One: Current state and system

overview

Mental wellbeing needs

1.

It is estimated that each year one in five people in New Zealand will experience mental

illness or significant mental distress, and over 50–80 percent of New Zealanders will

experience mental distress, addiction challenges or both in their lifetime. These

challenges have flow-on impacts for people’s whānau, families and communities.

2.

Suicide is a major issue in New Zealand, with persistently high suicide rates and a youth

suicide rate that is amongst the highest in the Organisation for Economic Co-operation

and Development (OECD). Every year over 550 people die by suicide. It is estimated that

1982

every year around 150,000 people will think about taking their own life; 50,000 will make

a plan to take their own life; and 20,000 will attempt to take their own life.

Act

3.

People’s mental wellbeing needs are strongly influenced by their experiences earlier in

life. Half of all lifetime cases of mental illness are thought to start by 14 years of age and

three quarters start by 24 years of age. Experiencing poor mental health early in life can

have lifelong impacts, including reduced participation in the future workforce, enduring

disability and/or poor family and social functioning Intervening early can however

significantly improve long-term outcomes and reduce future dependence on the health

Information

and social system.

Impact of COVID-19 on mental wellbeing needs

4.

COVID-19 and the measures taken to control it have affected the lives of all people in

Official

New Zealand. We have seen a direct impact on people’s mental wellbeing, including

higher levels of distress, anxiety, and a sense of uncertainty about the future.

the

5.

People’s mental wellbeing is also indirectly affected by the impacts of COVID-19 on

other areas such as education, income and employment, and family and community

relationships.

under

6.

Most people, whānau and communities can recover and adapt in challenging times, and

we have already seen positive examples of increased community cohesion, innovation

and resilience. However, we expect to see impacts on mental wellbeing and mental

health and addiction service demand continue to emerge in the coming months and

years, particularly associated with the potentially long-lasting economic impact of

COVID-19.

Released

Equity

7.

He Ara Oranga highlighted that there are significant inequities and unmet needs,

particularly for Māori, as well as for other population groups such as Pacific peoples,

refugees and migrants, rainbow communities, rural communities, disabled people,

veterans and people interacting with the justice system. People at certain stages of the

life course also experience inequitable outcomes, including young people, older people

and children experiencing adverse childhood events or in state care.

Appendix 1

8.

For example:

a. around 30 percent of Māori are estimated to have experienced mental health and

addiction challenges in the past 12 months, compared to around 20 percent of non-

Māori

b. Māori are approximately four times more likely than non-Māori to be subject to

compulsory treatment orders

c. the suicide rate among Māori is 2.1 times higher than among non-Māori

d. Māori and Pacific people are estimated to be more likely to have experienced

alcohol abuse or dependence in the past 12 months than people from other ethnic

groups (7.4, 4.2 and 2.2 percent respectively)

e. young people aged 15–24 years have the highest suicide rate of all life-stage age

groups (16.8 per 100,000 people compared to 11.3 per 100,000 people for the

general population), with Māori young people aged 15–24 years having a rate 2

1982.7

times higher than non-Māori young people

Act

f. males are more likely to experience alcohol abuse than females (16.3 percent

compared with 6.9 percent).

9.

People with mental health and addiction needs also experience disproportionately

higher levels of other health and social issues, such as poorer physical health outcomes,

homelessness, interaction with the justice system, unemployment and poverty. Poor

physical health and social outcomes are also associated with an increased likelihood of

people experiencing mental health and addiction needs.

Information

Mental health and addiction system overview

10.

Over the last few decades, the mental health and addiction sector has moved from an

Official

institutional base to a stronger focus on community-based services. There has been a

wide range of community services developed, as well as further development of

the

specialist and acute services.

11.

New Zealand’s health and disability system now provides a continuum of mental health

and addiction services. This includes:

under

a. wellbeing promotion for all New Zealanders

b. primary-level mental health, substance use and problem gambling services,

including support accessed through general practice and in the community

c. specialist services to support those with higher and more complex needs, including

crisis responses for people experiencing significant distress and forensic services for

Released

people interacting with the justice system.

12.

It is important to note that other sectors also contribute to mental wellbeing through

providing support for the social, economic and cultural foundations of mental wellbeing,

and through ensuring people’s mental wellbeing is supported through interactions with

the social, education and justice systems.

Appendix 1

Workforce

13.

The mental health and addiction workforce is diverse and includes a range of clinical

roles (eg, nurses, social workers, psychologists and doctors) and non-clinical roles (eg,

peer workers, employment support workers and cultural support workers). The

workforce in Vote Health-funded mental health and addiction services is estimated to be

around 12,500 full-time equivalent (FTE) staff and represents about 12 percent of the

total DHB workforce.

14.

In recent years, growth in the mental health and addiction workforce has been slower

than the increase in demand for mental health and addiction services. This is placing

increasing pressure on the workforce and services.

15.

He Ara Oranga called for new and different support options for New Zealanders, which

will require the development of a more diverse workforce and the use of workforces in

different ways. Workforce growth and development is a key focus of the Ministry’s work

1982

programme to implement the Government’s response to

He Ara Oranga (refer

Appendix Five for further information about workforce development)

Act

Mental health and addiction funding

16.

Historically, funding for mental health and addiction has focused on specialist mental

health and addiction services, which provided support to 3.7 percent of the population

in 2019/20.

17.

In 2018/19, of the approximately $1.53 billion of Vote Health funding spent on mental

Information

health and addiction (excluding pharmaceuticals and general medical services funded to

help treat or manage mental health matters):

a. around 95 percent was distributed via DHBs. Around 30 percent of this was used to

purchase services delivered by non-governmental organisations and primary health

Official

organisations

b. around 89 percent was spent on mental health services, and the remaining

the

approximately 11 percent was spent on addiction services.

18.

Mental health and addiction expenditure in DHBs is ‘ring-fenced’. This means that

although a DHB has discretion over where it allocates funding and can increase its

under

allocation to mental health and addiction, it cannot spend less than the previous year on

mental health and addiction.

19.

The Ministry of Health also contracts directly with NGOs and DHBs for some mental

health and addiction services. Additionally, some NGOs may receive funding from other

government agencies or through grants and philanthropic sources.

Released

1982

Act

Information

Official

the

under

Released

1982

Act

Information

Official

the

under

Released

1982

Act

Information

Official

the

under

Released

1982

Act

Information

Official

the

under

Released

1982

Act

Information

Official

the

under

Released

1982

Act

Information

Official

the

under

Released

Appendix 1

Appendix Four: Ministerial responsibilities

for decisions about special and restricted

patients

Purpose of appendix

1.

This appendix informs you of your role in the management of special patients and

restricted patients under the Mental Health (Compulsory Assessment and Treatment) Act

1992 (Mental Health Act).

Special and restricted patients

1982

2.

‘Special patient’ and ‘restricted patient’ are legal statuses determined when a Court

Act

orders that a defendant be detained in a forensic mental health facility for treatment.

3.

A defendant who is charged with an imprisonable offence and is suspected of being

mentally impaired can be assessed under the Criminal Procedure (Mentally Impaired

Persons) Act 2003 (Criminal Procedure Act). After an assessment, defendants can be

made a special patient if they meet the definition of ‘mental disorder’ in the Mental

Health Act.

Information

4.

The main categories of special patients are:

a. unfit to stand trial because of a mental disorder

b. not guilty by reason of insanity (as defined in the Crimes Act 1961)

Official

c. found guilty but the Court orders compulsory mental health treatment instead of, or

as well as, a prison sentence

the

d. people transferred from a Corrections facility (sentenced or on remand) to a forensic

mental health facility for treatment.

5.

Forensic mental health services provide treatment and rehabilitation services for

under

mentally disordered offenders, alleged offenders, or people who pose a high risk of

offending. Forensic mental health services provide inpatient treatment facilities (such as

secure units and step-down rehabilitation units) and community mental health services.

6.

When a person is made a special patient after being found not guilty by reason of

insanity, the order is for an indefinite period. A person found unfit to stand trial may be

Released

detained subject to a special patient order for up to half of the maximum sentence to

which they would otherwise be subject, to a maximum of 10 years, or until the person

becomes fit to stand trial.

7.

‘Restricted patients’ are compulsory mental health patients that present special

difficulties because of the danger they pose to themselves and others. The Court makes

decisions about restricted patient status based on an application from the Director of

Mental Health under the Mental Health Act.

Appendix 1

8.

The number of special patients is relatively small with about 130 people currently

detained under such provisions. There are currently only four people with restricted

patient status. Approximately 50 to 60 ministerial decisions are required for special and

restricted patients each year. Information on the nature and type of decisions you will be

required to make are outlined in the sections below.

Management of special and restricted patients

9.

The legal framework for managing special and restricted patients is set out in the

Criminal Procedure Act and the Mental Health Act.

10.

Special and restricted patients are detained for treatment in one of the five Regional

Forensic Psychiatric Services located in Auckland, Hamilton, Wellington (with a site in

Whanganui), Christchurch and Dunedin.

11.

Special and restricted patients are progressively reintegrated into the community by

1982

being granted leave from a secure forensic mental health facility. This approach enables

both the forensic mental health service and special patient to work towards planned

Act

treatment and recovery goals while giving due consideration to public safety.

12.

Each forensic mental health service conducts regular Special Patient Review Panels to

review the clinical progress of special patients and make recommendations for treatment

and rehabilitation. The Panels are made up of representatives from a multi-disciplinary

team that works with the special patient and may have a member external to the service.

13.

The Director of Mental Health may grant special and restricted patients up to six nights

Information

of leave per week (‘short leave’), requiring a return to hospital at least once per week

(section 52 of the Mental Health Act).

14.

Once a patient has demonstrated an ability to live safely and adaptively in the

community on unsupervised short leave, the responsible clinician can apply for longer

Official

periods of leave in the community, referred to as ‘ministerial long leave’ (section 50 of

the Mental Health Act).

the

15.

Once the responsible clinician is satisfied that the special/restricted patient no longer

requires management as a special/restricted patient, they may also apply for a change of

legal status. Figure 1 sets out the rehabilitative pathway for special and restricted

under

patients.

16.

The Minister of Health is responsible for making decisions on applications for long leave

and changes of legal status of certain special and restricted patients. These decisions

mark an important milestone in a person’s rehabilitation and reintegration into the

community. It can take years for a person to reach these milestones, and it is a

Released

meaningful occasion for them and their treating team.

Director of Mental Health

17.

The Director of Mental Health, Dr John Crawshaw, has oversight of the management of

special and restricted patients in New Zealand. The Director has specific powers in

relation to:

a. granting applications for short leave (section 52 of the Mental Health Act)

b. approving special patient transfers to another hospital (section 49)

Appendix 1

c. approving the return of certain inpatient special patients to prison, once their

mental health can be adequately managed in prison (section 47).

18.

The Director of Mental Health also considers applications for ministerial long leave and

changes of legal status and provides advice to assist the Minister of Health’s decision in

these matters. The Director is assisted by the Deputy Director of Mental Health and a

small team of advisors.

Ministerial decisions about special and restricted patients

19.

A special/restricted patient’s responsible clinician is accountable for the patient’s clinical

management in the forensic service. However, applications for long leave and changes of

legal status require a decision by the Minister of Health (and/or the Attorney-General for

certain categories of legal status).

20.

As Minister of Health you will be asked to make these decisions about special/restricted

1982

patients subject to orders under section 24(2)(a) of the Criminal Procedure Act, who have

been found not guilty of an offence by reason of insanity or deemed unfit to stand trial.

Act

21.

This level of decision-making reflects the seriousness of special and restricted patients’

status and the need to ensure that a wide range of factors are considered when making

decisions about such patients.

Ministerial long leave

22.

Under the Mental Health Act and the Criminal Procedure Act, you are responsible for

Information

granting long leave and approving changes of legal status for certain special and

restricted patients.

23.

When a responsible clinician assesses a special patient as fit to be absent from hospital,

an application will be submitted to the Director of Mental Health for consideration of

Official

long leave. The application must be supported by the Forensic Director of Area Mental

Health Services (DAMHS). The DAMHS is responsible for the operation of the Mental

the

Health Act in a district health board (DHB).

24.

Long leave applications will typically follow a sustained period of successful short leaves

in the community granted by the Director of Mental Health, up to a maximum of six

under

nights per week.

25.

The application contains supporting documents such as:

a. clinical progress notes and any notable incidents

b. a risk assessment and management plan for the patient while on leave

Released

c. the proposed conditions of leave

d. a certificate, signed by two medical practitioners, stating that the patient is fit to be

allowed to be absent from hospital (section 50(1) of the Mental Health Act).

25.

The Director of Mental Health will review all information provided, giving careful

consideration to the rights and rehabilitation needs of the patient and the protection of

the public. This cautious approach enables both the service and the patient to develop a

clear understanding of the course of treatment and future goals and gives due

consideration to public safety.

Appendix 1

26.

You would then be provided with a report setting out the Director’s advice and

requesting your decision. The report summarises the relevant aspects of the special

patient’s rehabilitative progress, risk and management plan. A glossary of terms used in

these health reports is enclosed for your information.

27.

If you choose to grant a period of long leave, a leave of absence is attached to the

health report for you to sign, giving effect to your decision. The leave of absence

includes standard conditions of leave and conditions that may be particular to certain

patients.

28.

It is convention to grant long leave for an initial period of six months, followed by

subsequent periods of 12 months if the initial leave is successful. If you choose to not

approve a period of long leave, no further action is required. The Director of Mental

Health will write to the patient’s responsible clinician about the reasons for refusing an

application.

1982

Revoking ministerial long leave

29.

Act

Occasionally the Minister is asked to revoke long leave under section 50(3) of the Mental

Health Act. This may be necessary if the conditions of leave are breached or if there are

concerns about the safety of the special patient or the public

30.

A revocation of long leave requires urgent attention, and the Minister is required to sign

the revocation within 72 hours of the patient’s return to hospital.

31.

While revoking leave is disappointing in terms of the patient’s progress, timely leave

Information

revocation demonstrates that the system in place for long leave is effective in terms of

identifying and managing risks to the patient and others.

Changes of legal status

Official

32.

Special patients acquitted on account of insanity may be considered for a change of

legal status. When a responsible clinician assesses that a special patient no longer

the

requires special patient status, an application will be submitted to the Director of Mental

Health for consideration. Applications must be supported by the Forensic DAMHS.

33.

The Director of Mental Health reviews the application, giving careful consideration to the

progress of the special patient

under and the protection of the public. The Director will provide

you with a health report summarising the special patient’s progress over time, their

treatment and rehabilitation activities, as well as any significant adverse events and risk

considerations, and a recommendation about the special patient’s legal status for your

consideration.

34.

Under section 33(3) of the Criminal Procedure Act you are required to decide whether

Released

continued detention for a special patient is necessary to safeguard the patient’s own

interests and the safety of the public. You will be assisted in your decision by advice and

a recommendation from the Director of Mental Health as noted above.

35.

In deciding whether a special patient status is no longer necessary for the safety of the

public or a person, considerations of risk are central. The Director’s advice will include

information on the special patient’s risk to self and others as assessed by the responsible

clinician using clinical tools. The range of protections and mitigations put in place by the

mental health service and the patient themselves will also be taken into account.

Appendix 1

36.

Considerations of risk are complex and multifactorial, but some key factors include:

a. the stability of the special patient’s mental state and abstinence from substance use

b. the special patient’s understanding of their mental health and how it links to their

offending

c. their level of engagement in treatment and rehabilitation plans and activities, and an

understanding of how treatment reduces their risk of future harmful behaviour

d. other protective factors such as relationship with family and meaningful

engagement in community life (such as work, learning and cultural activities)

e. the length of time living in the community without incident or recurrence of

behaviour mirroring the original offence

f. evidence of a robust management plan for the patient, should they be granted a

change of status

1982

g. whether they can be adequately managed as a compulsory patient under the

Mental Health Act.

Act

37.

If you find that the special patient’s continued detention is no longer necessary to

safeguard the interests of the person or the public, you may direct that the individual be

held as a patient subject to a compulsory treatment order under the Mental Health Act,

or that they be discharged.

38.

The reports append a direction for you to sign, should you choose to grant a change of

status.

Information

Change of status for special patients found unfit to stand trial

39.

Occasionally you will be required to make decisions about the status of special patients

who have been found unfit to stand trial. Most de

Official cisions about the legal status of this

group of patients are made by the Attorney-General, as set out in section 31 of the

Criminal Procedure Act.

the

40.

However, on rare occasions you will be required to make decisions about such patients

in concurrence with the Attorney-General. Clinicians can request a change of legal status

from the Minister of Health if the patient remains unfit to stand trial, but special patient

under

status is no longer required. This is unlikely to happen more than once a year.

Mental Health Review Tribunal findings

41.

The Mental Health Review Tribunal (the Tribunal) is appointed by the Minister of Health

under the Mental Health Act. The principal role of the Tribunal is to consider whether a

Released

patient is fit to be released from compulsory status. The Tribunal comprises of one

lawyer, one psychiatrist and one community member, and a number of deputy members.

42.

Every person subject to a compulsory treatment order is required to have their condition

reviewed at least every six months. Should a patient disagree with their responsible

clinician’s decision that they are not fit to be released from compulsory status, the

patient can apply to the Tribunal for a review of his or her condition.

43.

Applications for a change of legal status can arise when the Tribunal issues a certificate

stating that in their opinion, it is no longer necessary for a person to be held as a special

patient.

Appendix 1

44.

Section 80(5)(a) of the Mental Health Act requires the Tribunal to consider whether “the

patient’s condition still requires, either in the patient’s own interest or for the safety of

the public, that he or she should be subject to the order of detention as a special

patient.”

45.

The Tribunal describes the threshold for “requires” as high and falling between expedient

and desirable on one hand and essential on the other. The Tribunal will consider the

patient’s interest, the safety of the public and immediate and longer-term factors,

including what may happen if the patient is not a special patient.

46.

The Director of Mental Health will seek advice from the forensic mental health service on

their view of the patient’s condition and clarification of any aspects of the Tribunal’s

decision. The process for seeking a ministerial decision on a Tribunal finding is the same

as described in paragraphs 33 to 38.

Restricted patient leave and change of status

1982

47.

In relation to restricted patients, as the Minister of Health, you are also required to make

decisions about restricted patients’ detention where the:

Act

a. responsible clinician has applied for long leave

b. responsible clinician or Tribunal has found that a restricted patient remains mentally

disordered, but that it is not necessary for them to remain subject to restricted

patient status.

48.

Restricted patient long leave is handled the same way as special patients (see

Information

paragraphs 22 to 31). Change of legal status recommendations for restricted patients

must be agreed upon by you in concurrence with the Attorney-General.

Victims of special patients

Official

49.

Decisions around special patients are required to made within the current legislative

provisions; however, the notification and engagement with registered victims of special

the

patients has been problematic for the victims and the services and has led to adverse

media coverage on occasions.

50.

These challenges are due to how the legislation around victims’ rights is drafted and the

under

expectations and responsibilities for services arising from the Privacy Act, in particular

the Health Privacy Code with respect to the protection of the privacy of special patients.

51.

The Ministry is able to brief you separately on this issue and possible mechanisms to

address this.

Next steps

Released

52.

Dr John Crawshaw, Director of Mental Health and Addiction Services, is available to

assist you in making these decisions and to brief you further at your convenience.

Appendix 1

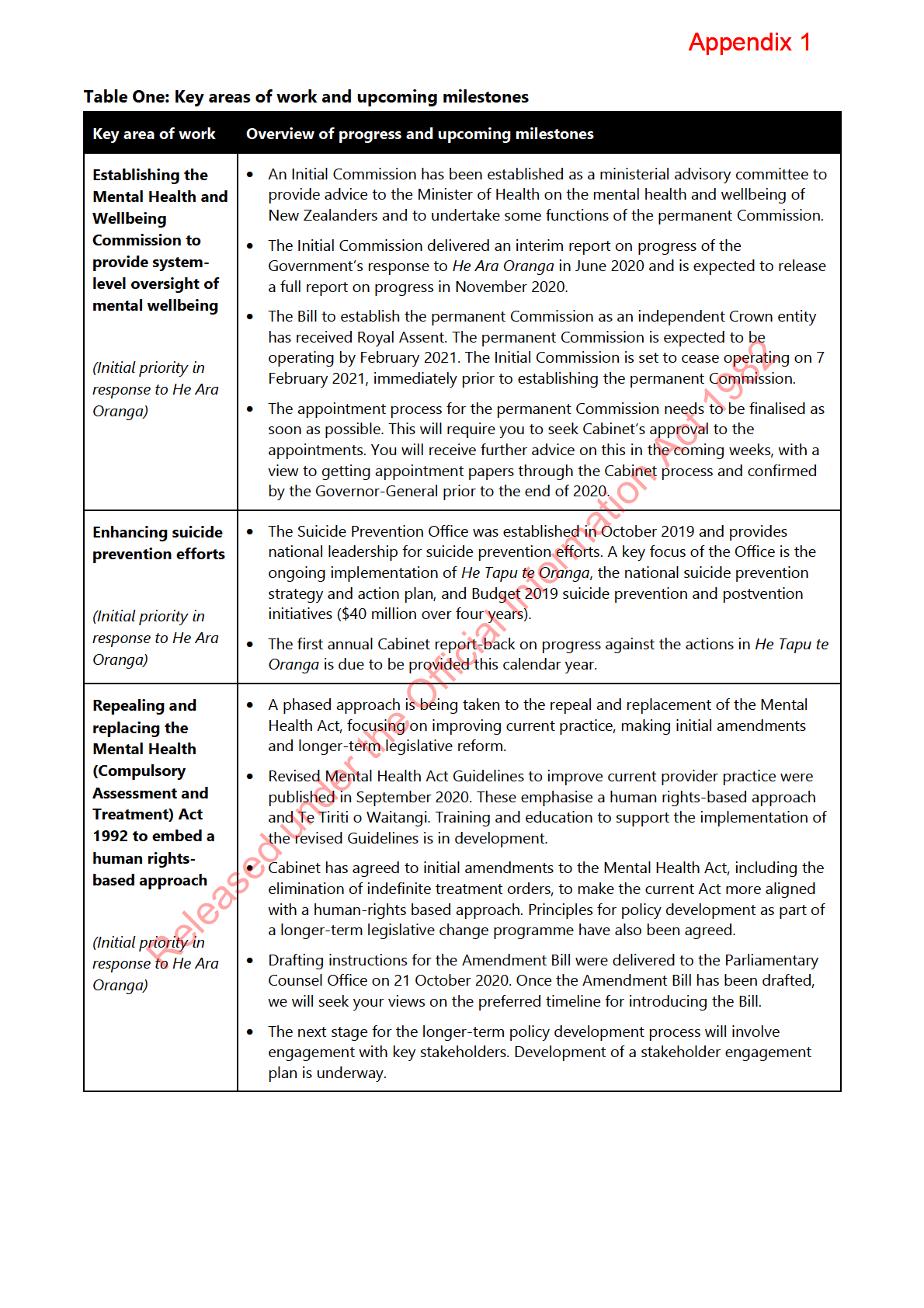

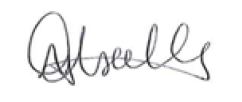

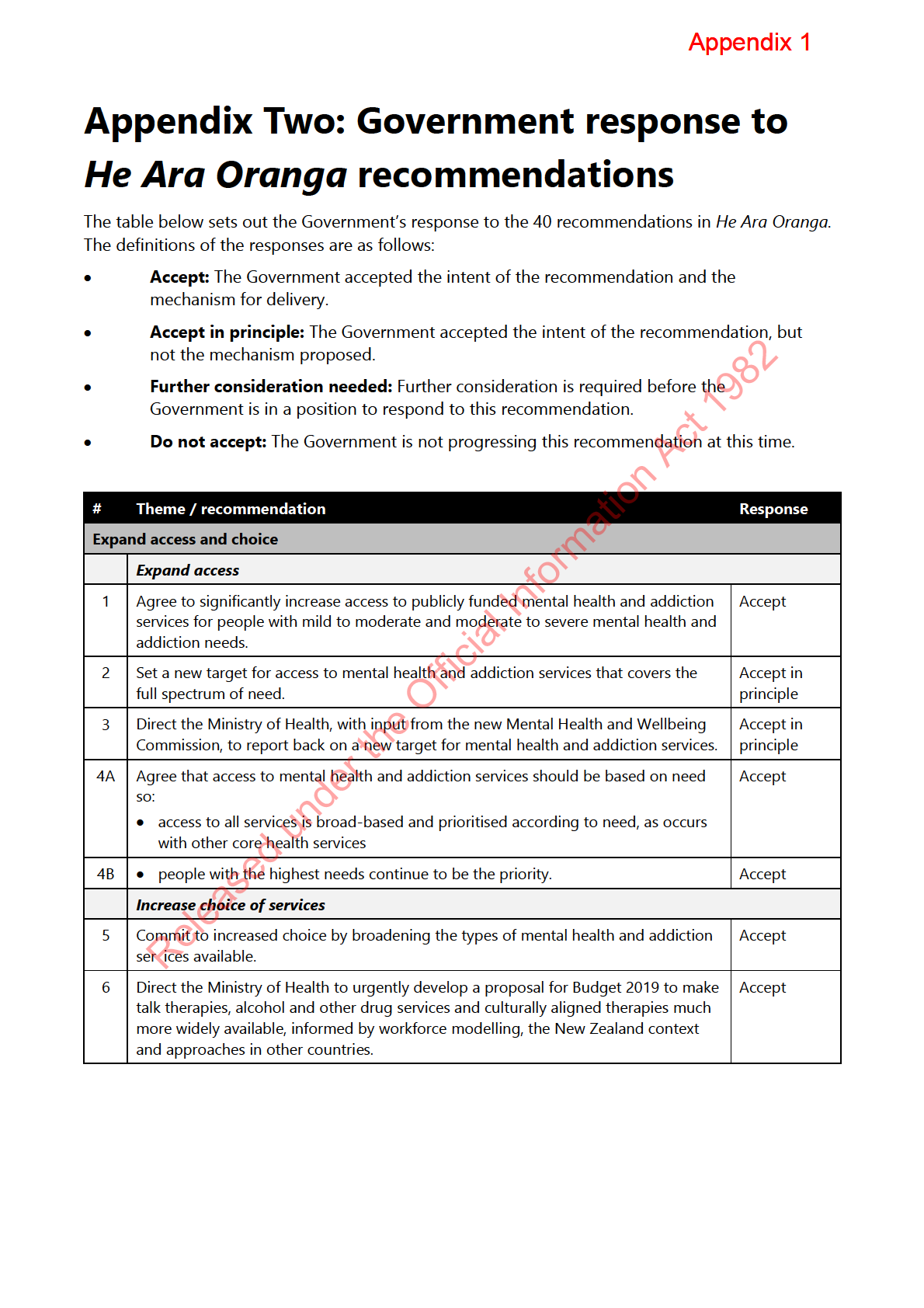

Figure 1: Special patient pathways

Special Patient found not guilty

Special Patient found unfit

Special Patient

by reason of insanity

to stand trial

transferred from Prison

s24(2)(a) CP(MIP) Act

s24(2)(a) CP(MIP) Act

s45 or s46 MHA

1982

Compulsory mental

Right to be treated as an

health treatment

ordinary patient subject to

Right to be treated as

cannot take place in

Mental Health Act (s44 MHA)

an ordinary patient

prison (s36 MHA)

Act

Detained in the hospital

until half maximum tariff

for most serious charge

Detained in a secure

If prisoner thought to be

Right to be treated in least

hospital

restrictive environment

mentally disordered, the prison

superintendent may apply for

MHA assessment

The special patient is carefully reintegrated back

into the community as their condition improves

Director can approve

leave up to six nights in

the community

Short Leave

Director can approve

(s52 MHA)

Information

leave up to six nights in

Clinical review at

DAMHS for

By Prisoner

the community

least every six

assessment

consent (s46

Short Leave

months

(s45 MHA)

MHA)

(s52 MHA)

Clinical review at

least every six

months

Ministerial Long Leave not available

Can approve leave

up to six nights in

the community

Official

Minister of Health can approve leave

Short Leave

for longer than six days on receipt of a

Joint ministerial decision with

Change of Legal

Certificate

(s52 MHA)

A-G if SP status considered

Ministerial Long Leave

medical certificate

received stating

Status

no longer necessary

Clinical review at

(s50 MHA)

no longer unfit

least every six

the

months

This leave can be revoked by

Minister (s51 MHA)

Attorney-General decision if

Ministerial Long Leave not available

no longer unfit

Certificate received indicating

under

Special patient status no

Change of Legal

longer necessary

Director of Mental Health

Status

can transfer Prisoner

Change to ordinary

Return to court

back to prison by

to face charges

MHA patient

DAMHS request

Minister of Health must

consider a change of legal

status to ordinary patient or

discharge

Released

Appendix 1

Glossary of terms used in special patient health reports

Criminal Procedure (Mentally Impaired Persons) Act 2003 (the Criminal Procedure Act)

The Criminal Procedure Act was the first significant revision of the law relating to mentally

impaired offenders in 50 years.

A defendant who is charged with an imprisonable offence and is suspected of being mentally

impaired can be assessed under the Criminal Procedure Act. At the conclusion of such an

assessment, the Court may find a defendant unfit to stand trial or acquit a defendant on account

of insanity.

The Criminal Procedure Act prescribes orders that the Court can make for the detention,

treatment and care of a defendant found unfit to stand trial or acquitted on account of insanity,

and for certain mentally impaired defendants who are convicted of an imprisonable offence.

1982

Director of Mental Health

The Director and Deputy Director of Mental Health have certain powers under the M

Act ental Health Act

in relation to special patients, including:

• the administration of matters relating to ‘special patients’, including approval of leave and

transfer

• the ability to apply to the Court for a ‘restricted patient’ order

• the ability to direct that patients be transferred between services

• the ability to instruct a district inspector to inquire into issues relating to the assessment and

Information

treatment of patients and proposed patients under the Mental Health Act

• the authority to inspect any aspect of a mental health service.

Directors of Area Mental Health Services (DAMHS)

Official

DAMHS are appointed to each DHB, as well as to the five regional forensic mental health services, by

the Director-General of Health. The forensic D

the AMHS have responsibilities in relation to special and

restricted patients, including:

• appointing health professionals to be responsible clinicians for each patient undergoing

compulsory assessment and treatment

under

• applying to the Director of Mental Health for the leave and transfer of ‘special patients’

• receiving applications for the compulsory assessment of a person detained in a penal institution

• deciding whether certain ‘special patients’ are fit to be returned to a penal institution

• directing the temporary return of certain ‘special patients’ to hospital

• receiving clinical reviews and Tribunal reviews of patients and special patients subject to a

compulsory treatment or

Released der.

District inspectors

District inspectors are lawyers appointed by the Minister of Health, with responsibilities to:

• make regular visits to hospitals and other services in the district of appointment

• conduct inquiries into any breach of legislation or breach of duty by persons employed in the

hospital or service

• monitor patients’ rights and investigate any complaints of breaches

Appendix 1

• ascertain views and wishes of patients during their course of treatment and assist where

appropriate with applications for review by a Judge or Tribunal

• prepare visitation reports for the DAMHS

• provide regular reports to DAMHS on the exercise of the district inspector’s responsibilities and

monthly reports to the Director of Mental Health.

Forensic mental health services

Regional forensic mental health services are responsible for the management of special patients and

restricted patients, within the legislative framework of the Mental Health Act and the Criminal

Procedure Act.

New Zealand legislation specifically allows for people who have been charged with or convicted of

an offence and who meet the definition of mental disorder in the Mental Health Act to be treated in

hospital for that illness. Treating the mental disorder is an important step in assisting an individual

to acknowledge and address the reasons for their offending and in doing so, can reduce the chances

1982

of future offending and significantly improve their wellbeing.

In managing special patients, forensic services are required to balance the treatment

Act and

rehabilitative needs of the individual with the safety of the public and the concerns of victims.

Index offence

The criminal offence that led to charges of which the special patient was found not guilty by reason

of insanity.

Information

Medical certificate

A certificate pursuant to section 50(1) of the Mental Health Act signed by two medical practitioners

stating that they have examined a special patient and found that they are fit to be absent from

hospital.

Official

Mental Health (Compulsory Assessment and Treatment) Act 1992 (the Mental Health Act)

the

The Mental Health Act provides the framework for the management of special patients, including

provisions for leave and transfer. The main sections of the Mental Health Act relating to the

management of special and restricted patients are:

under

• granting of ministerial long leave (section 50)

• granting of short leave by the Director of Mental Health (section 52)

• approving the transfer of special patients between facilities (section 49)

• enabling the transfer of prisoners into a forensic mental health facility for treatment (sections 45

and 46) Released

• approving the return of certain special patients to prison (section 47)

• enabling the Court to declare a patient to be a restricted patient (sections 54 to 56).

The key objectives of the Mental Health Act are to:

• define the circumstances in which compulsory assessment and treatment may occur

• ensure that both vulnerable individuals and the public are protected from harm

• identify the rights of patients and proposed patients and ensure those rights are protected

• ensure that assessment and treatment occur in the least restrictive manner consistent with safety

• provide a legal framework consistent with good clinical practice

• promote accountability for actions taken under the Mental Health Act.

Appendix 1

A ‘

patient’ under the Mental Health Act, means a person who is:

• required to undergo assessment under section 11 or section 13 of the Mental Health Act; or

• subject to a compulsory treatment order made under Part 2 of the Mental Health Act; or

• a special patient.

Mental Health Review Tribunal

The Minister of Health appoints members of the Tribunal pursuant to section 101 of the Mental

Health Act. One member must be a lawyer, one a psychiatrist, and the other a community member.

Key functions of the Tribunal in relation to special and restricted patients are:

• reviewing the condition of special patients found not guilty by reason of insanity, and reaching

an opinion as to whether “the patient’s condition still requires, either in the patient’s own

interest or for the safety of the public, that he or she should be subject to the order of detention

as a special patient” (section 80)

1982

• reviewing the condition of special patients found not unfit to stand trial, and reaching an opinion

as to whether they are no longer unfit to stand trial, and if so, whether they still require special

Act

patient status (section 80)

• reviewing the condition of patients who are subject to ‘restricted patient’ orders and reaching an

opinion as to whether the patient is fit to be released from restricted patient status (section 81)

• investigating complaints, including in relation to special and restricted patients (section 75).

Mental state

In clinical psychology and psychiatry, an indication of a person's mental health, as

Information determined by a

mental status examination.

Psychosis

Official

Psychosis occurs when a person loses contact with reality. The person may:

• have false beliefs about what is taking place, or who one is (delusions)

the

• see or hear things that are not there (hallucinations).

Responsible clinicians under

Key responsibilities of responsible clinicians include:

• determining whether or not a person is mentally disordered

• making applications to the Court for compulsory treatment orders (CTOs)

• overall management of the patient’s treatment

• regular clinical reviews of persons subject to CTOs and of ‘special patients’ and ‘restricted

patients’

Released

• ensuring consultation with the family or whānau of the patient or proposed patient unless there

are reasonable grounds not to do so.

Restricted patients

‘Restricted patients’ are compulsory mental health patients that present special difficulties because

of the danger they pose to themselves and others. The Court makes decisions about restricted

patient status based on an application from the Director of Mental Health under the Mental Health

Act. Restricted patient status is rare, with only eight people given this status since 1992. Restricted

patients have the same access to leave and change of legal status as special patients.

Appendix 1

Revoking ministerial long leave

Section 51 of the Mental Health Act permits the forensic DAMHS to direct that a patient on long

leave be admitted or readmitted to hospital if it is necessary ‘in the interests of the safety of that

patient or the public’.

Such an admission can only be for 72 hours, during which time the Director of Mental Health will

provide a health report to the Minister of Health seeking revocation of leave.

Special patients

‘Special patient’ is a legal status received when the Court orders that a defendant be detained in a

forensic mental health facility for treatment. Defendants can be made a special patient when they

meet certain criteria in terms of a mental disorder.

The main categories of special patients are:

1982

• unfit to stand trial because of a mental disorder

• found not guilty by reason of insanity (as defined in the Crimes Act 1961)

•

Act

found guilty but the Court orders compulsory mental health treatment instead of, or as well as, a

prison sentence.

Another category of special patient is where people in prison (sentenced or on remand) are

transferred under the Mental Health Act to a forensic mental health facility for treatment. The

person is transferred back to the Corrections facility when their responsible clinician considers their

mental health can be adequately managed in prison.

Information

When a person is made a special patient after being found not guilty by reason of insanity, the order

is for an indefinite period. A person found unfit to stand trial may be detained subject to a special

patient order for up to half of the maximum sentence to which they would otherwise be subject, to a

maximum of 10 years, or until the person becomes fit to stand trial.

Official

Special Patient Review Panel (SPRP)

the

Each forensic mental health service conducts regular SPRPs to review the clinical progress of special

patients. The Panels are made up of representatives from a multi-disciplinary team that works with

the special patient (e.g. psychiatrists, nurses, social workers), and may have a member external to the

service.

under

The special patient appears before the panel with support people (such as family and whānau) for a

discussion about their progress in the preceding period. The SPRP will then make comments and

recommendations for the patient’s treatment and management plan, including recommendations

about leave and change of status.

The SPRP s recommendations serve as a second multi-disciplinary team opinion for ministerial leave

Released

or change of legal status decisions and are referenced in the health reports to the Minister of Health.

Treating team

The treating team is a multi-disciplinary team that works with the special patient. Treating teams

may include psychiatrists, nurses, social workers, cultural support workers, kaumātua, addiction

practitioners, and peer support workers.

1982

Act

Information

Official

the

under

Released

Appendix Six: Indicative milestones through to 2023/24

Appendix Six: Indicative milestones through to 2023/24

Appendix 1

2020

2021

2021/22

2022/23

2023/24

2020/21 Q2

2020/21 Q3

2020/21 Q4

▪ Commence de ivery of expanded Māori services

▪ Commence phased delivery of new Māori services

▪ Integrated Primary Mental Hea th and Addiction Services

s

being delivered in over 100 general practice sites in 15 DHB

▪ Commence phased de ivery of expanded and new youth

▪ Commence phased delivery of new Pacific services

areas, providing coverage for around 1.5 mil ion people

services

Expanding

▪ Commence procurement for next tranche of youth services

▪ Commence delivery of new B20 services for tertiary students

Access and

▪ Commence procurement of new B20 services for tertiary

Choice

students

)

1982

▪ Commence estab ishment of Waikato Alcohol and Other

▪ Commence procurement processes for Waikato AOD

▪ New refined drug testing regime for Auckland AOD

▪

s

Drug (AOD) Treatment Court

treatment court

Treatment Court starts

▪ Sites identified for additional B19 primary AOD services

▪ Procurement of additional B19 primary AOD services

▪ Waikato AOD Treatment Court starts

underway

Addiction

▪ Contracts in place for additional B19 primary AOD services

Act

▪ Commence services of two additional Pregnancy and

)

Parenting Services sites (Whanganui and Eastern Bay of

Plenty)

▪ Report-back to Cabinet on progress implementing

He Tapu

▪ Additional LifeKeepers suicide prevention training

▪ Development of updated media guidelines and engagement

▪

s

te Oranga, the suicide prevention strategy (TBC pending

workshops and e-learning modules commence

with media completed

Ministerial decisions)

▪ Commence phased delivery of face-to-face bereavement

(

▪ First round of B19 Māori and Pacific Suicide Prevention

response service (note: national on ine services commenced

Suicide

Community Fund projects underway

in May 2020)

Prevention

▪ One year anniversary of Suicide Prevention Office

▪

s 9(2)(f)(iv)

s 9(2)(f)(iv)

Information

▪ Finalise updated

Kia Kaha, Kia Māia, Kia Ora Aotearoa:

▪

▪

s

COVID-19 Psychosocial and Mental Wel being Recovery Plan

s 9(2)(f)(iv)

s 9(2) f)(iv)

Psychosocial

(the Psychosocial Plan) to reflect stakeholder feedback

plan &

(

▪ Release updated Psychosocial Plan (TBC)

longer-term

pathway

Official

▪ Provide drafting instructions for initial amendments to

▪ Introduce initial amendment Bil (TBC pending Ministerial

▪ First reading and Select Committee consideration of initial

▪

▪

▪

Par iamentary Counsel Office (PCO)

decisions)

amendment Bil (TBC)

s 9(2)(f)(iv)

s 9(2)(f)(iv)

s 9(2)(f)(iv)

the

▪ Commence targeted stakeholder engagement to inform

Mental

policy development for repeal and replacement of the Act

Health Act

under

▪ Initial Commission delivers report on Government progress

▪ Permanent M ntal Hea th & Wel being Commission

▪ Monitoring and oversight of mental wel being activities

s

responding to

He Ara Oranga

established

Mental

Health and

▪ Finalise appointment process for permanent Mental Hea th

▪ Initial Commission term ends

(

& Wel being Commission (TBC pending Ministerial

Wellbeing

decisions)

2

Commission

▪ Commence procurement of additional B19 digital supports

▪ Commence service de ivery of Wel Child Tamariki Ora

▪ Commence delivery of additional B19 digital supports

s

Enhanced Support Pilots in Counties Manukau

▪ Commence service de ivery of B19 Wel Child Tamariki Ora

s

s 9(2)(f)(iv)

Released

Enhanced Support Pilot in Lakes

(

▪ Commence service delivery of pilot to improve transitions

Other

from acute mental hea th inpatient units (part of

priority MHA

Homelessness Action Plan)

)

initiatives

▪

s 9(2)(f)(iv)

Note: This is an indicative overview of potential activities to implement priority areas of the Government’s response to He A ra Oranga and the confirmed investment in mental health and addiction. Some activities are unconfirmed and subject to future Ministerial or Cabinet decisions. This is not intended to pre-empt or advise on those decisions.

Document Outline