Integrated Targeting and Operations

Centre (ITOC)

2016 Review

under the Official Information Act 1982

Simon Murdoch

Released

May 2016

link to page 3 link to page 5 link to page 5 link to page 5 link to page 6 link to page 9 link to page 11 link to page 13 link to page 18 link to page 18 link to page 21 link to page 21 link to page 21 link to page 22 link to page 22 link to page 23 link to page 23 link to page 25 link to page 25 link to page 25 link to page 27 link to page 29 link to page 32

Contents

Foreword............................................................................................................................... 3

Part One: ITOC – Evolutionary Development ....................................................................... 5

Timeline/Milestones ........................................................................................................... 5

The National Targeting Centre (NTC) – Forerunner of ITOC ............................................. 5

The 2008-13 Border Strategy and Priority Work Programmes ........................................... 6

1982

From NTC to ITOC (Expectations – Mission and Functions) .............................................. 9

The Targeting Function ................................................................................................... 11

Act

Part One: Summary Observations/Conclusions ............................................................... 13

Part Two: Value Proposition ............................................................................................... 18

Post-Interview Key Points and Findings about Current Value .......................................... 18

Value Proposition ............................................................................................................ 21

Information

Offshore arrangements and event-specific domestic operational coordination: ............ 21

Maritime border knowledge management – awareness and coordination: ................... 21

Official

Maritime targeting: ....................................................................................................... 22

the

Joint target analysis and development: ........................................................................ 22

ITOC configuration: ...................................................................................................... 23

Overall impact – border sector mission and indicative development goals: .................. 23

under

Part Three: Conclusions, Recommendations and Suggestions .......................................... 25

Conclusions ..................................................................................................................... 25

Recommendations and Suggestions ............................................................................... 25

Released

Annex A: ITOC Prehistory and Timeline ............................................................................. 27

Annex B: Terms of Reference and List of Agencies Consulted .......................................... 29

Annex C: Australian System ............................................................................................... 32

Page 2 of 32

Foreword

This Review was commissioned by the governance group for ITOC which set its Terms of

Reference (see Annex B). The Reviewer proposed a methodology which was accepted. It

involved the circulation to interested agencies and within Customs of a questionnaire based

around the TOR; this was followed by in- person interviews, covering senior and mid-level

managers, past and present, as well as two CEOs. Those agencies and entities which were

thus consulted are listed under Annex B but the views of individuals have been generalised

in this report. The Reviewer received full cooperation and views were expressed thoughtfully

and frankly by all interviewees.

1982

The Review was supported logistically by Customs. The Reviewer expresses appreciation to

Act

Customs for this support and warmly thanks Matt Haddon for his expertise and his many

other helpful contributions.

What follows in the report is largely self-explanatory. It was clear enough from the Terms of

Reference and became even more apparent as the Review progressed, that the story of

ITOC cannot be divorced from the evolution of border sector institutional architecture in

machinery-of-government terms. Shifts in strategic priorities for border protection between

human and economic security have also had a bearing on the perceived value of ITOC as a

Information

small but capable asset for the collective border community. Customs has persisted in

articulating this element of value in the face of developments which went in other directions.

The big question, which the Review was asked to explore, is whether ITOC has a future as a

Official

sector-serving entity. Answering it took the Review to a wider underlying question – whether

capability developments within the sector member agencies over the seven years since

ITOC`s establishment had, in aggregate, carried the sector significantly closer to the point of

the

“a single border system” which had been the declared goal of the 2008-13 Border Sector

Strategy. The extent to which this Strategy, which set the developmental direction for the

border sector, remains relevant is unclear.

under

The conclusions and recommendations of the Review turn both of these questions back to

the Border Sector Governance Group with some suggestions about where future value may

lie. Whereas some officials hold a view that “things have moved on” and the moment for a

collective version of ITOC has passed, it may be more fruitful to think about ITOC in terms

less of organisational form than of risk management functions, of how they need to evolve or

improve in future to meet dynamic border sector risks, and then of what institutional

Released

architecture best suits these needs. Some of these functions are currently being performed

quite efficiently by agencies, and collaboratively up to a point. But they may need to advance

to higher levels of collaboration in terms of system harmonisation and practice

interoperability if the sector is to continue to serve national and international security well.

The Reviewer also took into account that in the period since ITOC was established and the

sector Strategy was first developed, there have been important changes in New Zealand’s

national security policy settings, management doctrine, and the governance arrangements

under the Officials Committee for Domestic and External Security Coordination (ODESC). A

Page 3 of 32

refresh of the 2008-13 Strategy by the Border Sector Governance group (BSGG), as is

recommended, would also be worthwhile on these grounds.

The Review contains, in Part One, an evolutionary history of ITOC and commentary on the

2008-13 Strategy, as well as on the emergence of advanced targeting as the critical new

technology for border risk management. Part Two is about ITOC`s value as seen by

interviewees in terms of its present utility as a sector and a Customs asset and of what

future value an entity with ITOC`s functions and capabilities could provide within the border

sector and beyond. Part Three contains conclusions and recommendations, some of which

are necessarily speculative and are therefore cast as ideas for further follow up.

1982

Act

Information

Official

the

under

Released

Page 4 of 32

link to page 5

Part One: ITOC – Evolutionary Development

Timeline/Milestones

1.

Although ITOC was not formally established until 2011, Customs had been reshaping,

and modernising its approach to border protection and control for some years. It was

well aware of the synergies to be unlocked by de-siloisation done in tandem with the

other border agencies. The option of a structural unification of the sector had been on

the table in New Zealand, as well as internationally, for even longer. Annex A outlines

this evolutionary story, including the various developmental milestones and factors

1982

influencing the eventual shape and character of ITOC. The following sections cover

the most recent developments in greater detail.

1

Act

The National Targeting Centre (NTC) – Forerunner of ITOC

2.

With the advent of tighter requirements for advance information about passenger and

goods movements (especially post 9/11), and leaps in technology (for data

management and bio-identification) new border control tools became available for

developed countries. These tools enable the targeting function. Targeting, in the

Information

border context, applies to the functions and practices which aim to prevent border

security breaches by the early application of screening and profiling techniques to

identify probable risk actors and threat behaviour patterns. By the use of analysis the

profiles can be applied to mass data to narrow the risk-scape progressively, and to

prioritise decisions about threat reduction, interdiction and investigation operations.

Official

Customs in particular recognised this as a step-change in border security tradecraft –

a generic capability.

the

3.

Customs also believed that a wider public management doctrine shift (“managing for

outcomes”) which demanded cross-sectoral responses to cross-cutting problems, and

emphasised sector clusters, could bring border sector architecture issues back into

under

focus. It might even reopen the option of a full merger of all border management

functions under a single agency, but at least it could mandate non-structural

integration and accelerate a process across agencies of harmonised risk management

involving certain common border security functions, and shared services affecting the

operational/enforcement frontline, or the enabling infrastructure behind it.

Released

4.

The common function Customs foresaw as being particularly suitable for integration

was targeting. A multi-agency “integrated border targeting team” could deepen the

range and quality of information and intelligence about border sector risks and threats

upon which the targeting function depends.

1 The documentation upon which this summary is based comes from Customs files. There appears to have

been no recorded interagency reporting (e.g. Joint Ministerial submissions, budget papers or ODESC

briefings) and it is assumed that such interagency consultation as occurred took place informally or on the

fringes of sector governance (BSGG) meetings. As part of its NTC and ITOC project management, which

reported upwards to Customs Executive Leadership Team, Customs kept border partner agencies informed,

but not consulted. Until recently, no standing body for ITOC governance existed.

Page 5 of 32

5.

This expectation was clearly reflected in the NTC project documentation. Customs

planned not just the Customs-specific “NTC Implementation Project”, but also a

multiagency “NZ Inc Implementation Programme”.

6.

At the core of the NTC Project was Custom`s ambition to address “border and security

risks” from people, craft and goods holistically. This would enable Customs to act more

coherently across its various enforcement activities and efficiently in terms of not

having its regimes set at an overall level of security precaution that would impose

heavy compliance costs on legitimate traders or travellers. Customs aimed for better

integrated information, improved knowledge management (especially intelligence

analysis) and to achieve a new standardised targeting process, with common rules for

profiling within Customs. This would require both a structural realignment and

reallocations of command, control and communications. The NTC was to be a

1982

centralised entity, part of the new Intelligence, Planning and Coordination (IP&C)

group providing services to operational staff and decision-makers based in the field.

Act

7.

The question of how Customs should manage information and share knowledge

(especially knowledge derived from sensitive intelligence) was part of an IP&C

realignment programme. But in fact, although it utilised intelligence analysts in the

targeting teams and was part of the IP&C group which included Intelligence, NTC itself

was established as a separate unit to the existing intelligence component. Some of

Customs’ key overseas partners, by contrast, post 9/11, had undertaken broader re-

Information

structuring and institutional realignments aimed directly at the fusion of all forms of

border security knowledge, including what had previously been very

compartmentalised intelligence. This was not solely in order to strengthen homeland

security against foreign passenger threats. Facilitation of trade became more

dependent on the perceived quality of border security management (particularly for

Official

exports to the United States of America).

the

8.

In June 2006, the NTC commenced operations at a Customs’ premises in Mangere

with a staff of 55 Customs’ employees. Partner agencies with a presence at Mangere

were initially the Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry/Biosecurity New Zealand; later

Immigration New Zealand and Maritime New Zealand. Police were not a partner at this

under

time. The costs of establishing the NTC were borne entirely by Customs from within

baseline

.

The 2008-13 Border Strategy and Priority Work Programmes

9.

This public document emerged from an extensive Cabinet process. The first of its kind,

Released

it was issued in October 2007 by the chief executive level Border Sector Governance

Group (BSGG) created a year earlier after a State Services Commission (SSC) review.

It defined the border sector as a group of six agencies – Customs, Labour (Immigration

NZ), the Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry, the Ministry of Transport (and its three

Crown Entities – Civil Aviation Authority, Aviation Security and Maritime New Zealand),

the New Zealand Food Safety Authority and the Department of Internal Affairs. BSGG

core membership was the first four.

Page 6 of 32

10. The structural options for a merger/amalgamation to create a single border operations

force, or a unified border service, or the further step to a single “homeland security”

agency – in vogue overseas – had all been rejected by Cabinet. Instead it opted for “a

more functional approach” to deliver “joint sector outcomes” emphasising systems

integration. It would not entail legal or administrative change to the current

responsibilities of any agency. Although the Ministerial level is not mentioned in the

strategy, the Cabinet portfolio arrangements were not changed.

11. The New Zealand border sector would therefore remain vertical in its architecture of

six agencies (and other public entity stakeholders, all with border-related missions or

interests) but, by intent, increasingly horizontal in output production and delivery,

progressively building one border management system. This was a federated model

resting on collaboration principles, firm but not binding; agencies would apply them

1982

“according to their own planning and service delivery needs”. The strategic objective –

system integration – would be brought about progressively through dedicated

Act

programmes of work to realign agency machinery and processes to make them more

accessible and interoperable, particularly at the physical border. A sector budget line

would be created. An active governance posture by BSGG (not just passive monitoring

but “directive/overseeing”) was seen as essential. Four work programmes were to be

given priority. Each would have projects managed by its own multidisciplinary, cross-

agency team.

Information

12. Of the four priority work programmes thus established, one in particular was relevant

to ITOC and this Review – the risk-profiling of people, goods and craft before they

arrive at the physical border. The goal was to develop “a shared border sector

intelligence/risk framework and related border alert system to service whole sector”.

This was further defined under the protection header in the Border sector operational

Official

context and work programme priorities outlined in Figure 1 below.

the

Facilitation

Protection

Partnership

under

Operational environmental drivers

- Speed/cost/effectiveness trade offs

- International competitiveness

- Complexity and change

- International developments

Intelligence/Risk/Profiling environment

Released - Links between types of offending

- Constraints and opportunities

- Complex problems and need for ready

response to threats

- Technology is a key enabler

- Tools to target risk without increasing staff

numbers

- Border agencies at different stages of

intelligence, risk management and profiling

development

Page 7 of 32

Facilitation

Protection

Partnership

Aims for intelligence, risk and profiling

environment

1. Make available the best possible information to

front line decision-makers

2. Increase protection through coordination and

collaboration

Enabling priorities

Intelligence/risk/profiling

Develop a shared border sector intelligence/risk

framework and related border alert system to

service whole sector

Identity

1982

Develop identity processes at the border for

facilitation, protection and partnership

Act

Sector-wide operational design principles

1. Some areas of operation will need national consistency.

2. Technology is a significant enabler but needs to be future-proofed, and accompanied by behaviour

changes to make it work.

3. Existing investments will be optimised as far as possible; more than one agency will use border

assets

4. Border agencies and stakeholders will leverage off one another’s’ knowledge and standards and

border infrastructure needs. Costs will be met appropriately across the system.

Information

Intelligence/Risk/Profiling

General

Need holistic picture of the border and resulting

risks. Effective risk management is needed to

enable facilitation.

Official

Security of Information

Need to balance security of and access to

information

the

Need workable privacy and information security

frameworks

Tools & methodologies

Standards are required, with ANZS 4360:2004

under as the base.

Technology is a key integration tool

Use technology for staff to do more value-d

adding tasks.

Links

Whole-of-border intelligence-enforcement

flows.

Released Private sector is an important source of

information

Need for interoperability with other jurisdictions.

Figure 1: Border sector operational context and work programme priorities – Protection

Page 8 of 32

From NTC to ITOC (Expectations – Mission and Functions)

13. Customs’ IP&C Review (commenced in mid-2009 after the change of government)

described NTC as “the first step” towards a more strongly coordinated approach to

border risk management and the targeting of high risk persons and goods. The next

step, as seen by Customs, was to enhance support for more rapid and efficient

responses to identified border threats. This would be achieved by moving the targeting

function and elements of Customs’ then operational planning and coordination

arrangements closer together.

14. In developing the ITOC project charter (March 2010) Customs continued, as it had with

NTC, to think in wider sectoral terms, aiming at consistency with the Strategy. The

Charter said ITOC was to be “a multiagency-focussed facility, and with growth in

1982

membership in the future, may be a catalyst to the merging of border management

functions”. Elsewhere in project documentation the need to develop multiagency

Act

accords and to establish multiagency national standards and shared governance

arrangements (a Joint Interagency Coordinating Group) are outlined.

15. The particular Customs’ elements to be centralised in ITOC were:

i.

The watch function – previously a function performed regionally in ports-based

operational teams on a limited hours schedule. Now ITOC would provide a

Information

continuous nationwide over-watch.

ii.

The planning function – if a response operation required extra Customs’

resources (e.g. from another workgroup), ITOC`s planners would plan for and

coordinate the deployment of the increment/reinforcement elements and redirect

Official

or prioritise human or other resources for the operation in question. The

provision of analytical and logistic support for an operation commander would

the

continue to come from the relevant operational work area to be augmented by

ITOC as required.

iii.

Knowledge management and decision support by maintaining higher-level

under

domain and situational awareness, including the contact with other agencies

contributing to a particular operation. It was clearly stated that the command of

operations in the field was not ITOC`s role except in certain specific

circumstances. The default position remained that the relevant local/regional

operations group would command.

iv.

Targeting – the risk profiling and target development process which, at this time,

Released

was seen as both a growing necessity for Customs’ own business needs and

potentially a multiagency function, an integral part of the ‘single border

management system’ under the 2008-13 Strategy.

16. With a common location and an integrated staff the new ITOC would offer 24/7/365

day services. It would identify risks, assess threats, provide targeting directions, help

plan responses to threats, and help direct or coordinate the conduct of operational

responses as required.

Page 9 of 32

17. ITOC would also better serve as the clearing-house and contact point for a range of

Customs overseas liaison interests and border sector/homeland security entities with

who very close partnerships had been established.

18. Both this new operational coordination (support) function and the targeting function

would consume and generate information. ITOC would also need to become the

institutional home for a multiagency approach to ‘border sector awareness’ through the

fusion of information and intelligence-derived knowledge between Customs and a

group of existing and potentially new agency partners. The main objective regarding

fusion was not necessarily a single intelligence repository but to better share law

enforcement and regulatory information across the border sector.

19. This change also brought Customs’ targeting function a step closer to its Intelligence

1982

group. The new premises at the Auckland Customhouse offered improved security

features making it easier, in principle, for other agencies to bring various kinds of

Act

information into a common space where it might become fused, or at least more

readily available. Unlike the Mangere facility, ITOC would also have the ability to

handle highly classified intelligence.

20. Besides the opportunity for better sharing of strategic knowledge (the border risk-

scape), Customs foresaw that the real-time situational awareness required for

operational or tactical decision-making could also be generated on a fused or

integrated basis between agencies (the ITOC Charter had expressed the aim as “to

Information

ensure integration of collection, sharing and analysis of intelligence with respect to

targets that are a threat to border security”). Customs incorporated a state-of-the-art

visual display system – a video wall – in the design for the new ITOC premises in the

Auckland CBD. Planning provision was also made to develop the means to deliver an

Official

even fuller situational awareness capability – a ‘Common Operating Picture’ – in the

form of an electronic capture and display of multiple activities in real time,

the

simultaneously available to both frontline and rear. This multi-layered geospatial

capability had initially been a military tool but law enforcement and homeland security

entities overseas had been adopting it more widely.

under

21. Customs’ project documentation for ITOC acknowledged some risks, including failure

to secure interagency uptake and participation. Behind this (although not as explicitly

stated) were some deeper constraints. Fusion as a concept had known limitations.

Some would be imposed between domestic agencies by standard operational (‘need-

to-know’) security. Furthermore, certain types of information from overseas partners

whether strategic or tactical, could not be shared freely; it was generally vouchsafed by

one counterpart to another (e.g. Customs to Customs) under specified conditions of

Released

use. It had to be handled according to the rules and restrictions of the originators.

Absent a new joint information management platform, or at the least, a clear set of

information management protocols, these were enduring constraints for sector wide

knowledge management.

22. Similarly, the aim of a higher level of national cross-agency interoperability in other

functional areas (e.g. interventions and investigations) also had ongoing restrictions

because the agencies had no common legal basis for exercising the various powers

Page 10 of 32

required to enforce border controls, and this in turn created different doctrine and

operational practices.

23. Customs had a clear idea of what sorts of operations might be supported by ITOC.

Their operational environment is made up of pre-border, at-border and post-border

activities. At each of these, there are three kinds of operations:

i.

‘routine’ enforcement – normal operational activity in ports and airports.

ii.

‘deliberate’ – pre-planned operations to mitigate or neutralise identified risks and

latent or materialising threats (including those exposed by targeting) of a certain

magnitude or complexity.

1982

iii.

‘contingency’ – time critical interventions against actual events where border

security had been or was about to be breached, and response operations

Act

mounted.

24. Customs’ experience was that it could have all three types of operations in progress at

any one time, and it could also be a party to operations which border partner agencies

had initiated for their own or wider national security reasons.

25. It was also Customs’ belief that beyond its value to Customs, ITOC, with its Auckland

CBD location and then technical advancement opportunities, offered a new capability –

Information

a multipurpose infrastructure and scaleable platform – for multiagency command,

control and coherence in either deliberate or response operations of a certain scope

and complexity.

26. In mid-2011, ITOC commenced operations in the Auckland CBD with a staff of 65

Official

Customs employees. Partner agencies with a presence were MPI, NZSIS, Immigration

NZ and Maritime NZ; Police and AvSec joined later. The costs of establishing ITOC –

the

both capital and operating – were borne exclusively by Customs from within baseline

although the video wall received extra appropriation via a business case. The average

annual Customs’ budget allocation for ITOC over the past three years is $4.4 million.

under

The Targeting Function

27. Customs’ institutional grasp of the power of targeting matured between NTC and ITOC

and has continued to do so with uptake of new technology supported by other

investments in, and practice with, profiling tools. The ability to access mass data about

Released

goods and people flows prior to the physical movement, to screen it electronically and

to integrate layers of information and interrogation into it so as establish risk profiles

and selectively target them is now central to its risk management.

28. Recent performance data suggests that productivity, in terms of alert hit rates, is

increasing exponentially and can be directly associated to the capacity of the

technology to cope with increases in the number of profiling rules with which the data

can be interrogated. There appears to be a virtuous circle as inputs from profiling,

intelligence and frontline feedback are sequenced into the process by experienced

Page 11 of 32

operatives. As a business practice which enables border risk management, targeting is

now in common use amongst overseas partners with whom important profiling inputs

are exchanged.

29. The underlying technology and the applications are the same or similar. However,

there are some fundamental differences in how the three New Zealand border

agencies need to set their risk parameters and how much reliance they put on the

frontline intervention. Customs can rely on its targeting processes to treat a bigger

proportion of travellers and traders as trustworthy (not requiring primary line scrutiny)

based on their profiling than can MPI. MPI’s risk parameters have to cover

unintentional or adventitious contamination or infection. Immigration NZ, for reasons

related to the role played by agents in its pipeline, and because it is still building its

profiling infrastructure and expertise, regards primary line scrutiny, as a more 1982

significant input to its risk management. Immigration NZ therefore needs a high level of

interaction and feedback between its frontline and its targeting staff. There are also

Act

differences in the quality of advance information between the maritime border and the

air border. In short, at present, there are parts of the targeting function where agencies

interests, capabilities and practice are not uniform or convergent.

30. Nonetheless targeting can still be considered a common business practice and border

sector craft and the agencies can still benefit from harmonising practice – to some

considerable extent. The potential for joint or teamed approaches lies most clearly in

Information

the application of data analytics to information and core data sets which are

increasingly being interfaced, and then in the application of profiling tools enriched by

intelligence inputs to the mass information. It is a progressive knowledge refinement

process which can utilise common infrastructure, methodology and practices.

Official

31. Given that the process must accommodate differences in type and nature of the risks,

these inherent commonalities in respect of core information and data sets, targeting

the

tools, and techniques and methodologies across the sector, will need to be leveraged

in practice and could be expected to emerge organically as practice matures.

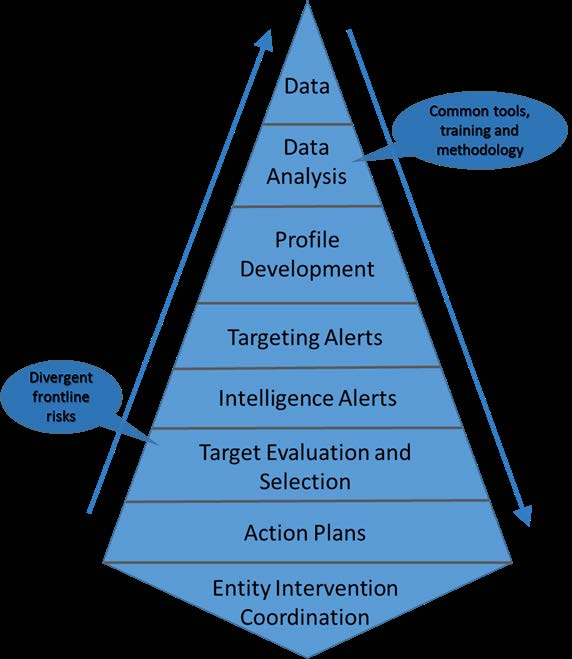

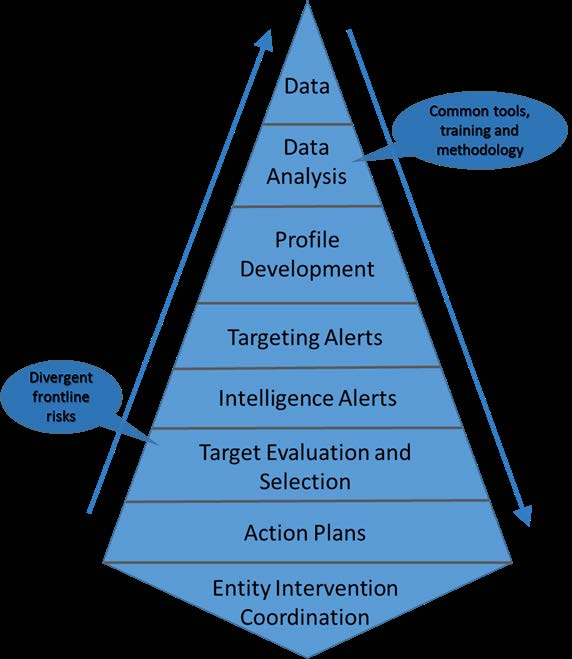

32. The following diagram (

Figure 2) considers a commonality and divergence continuum

under

with regard to the border risk targeting functions. This primarily looks at traditional law

enforcement security risks versus biosecurity risks although can be applied to the

majority of agencies risks to a greater or lesser extent. It leads to the suggestion that

the most fruitful area for multiagency collaboration lies at the top of the process where

the commonalities are greatest.

Released

Page 12 of 32

1982

Act

Information

Figure 2: Targeting commonality and divergence continuum

33. MPI and Customs have further significant developments at hand in respect of goods

Official

and trade (beyond the Joint Border Management System (JBMS) Trade Single

Window). The broader aim of the JBMS project is to provide a greater level of

the

information access, risk assessment and work flow management for both agencies.

This, when fully rolled out, will shift data sharing and integration to a new level not so

far seen elsewhere in the New Zealand border sector. In this sense the ‘facilitation’

objective prioritised in the 2008-13 Strategy, at least as it affects trade and commerce,

under

has been achieved by Customs and MPI.

34. Whilst the JBMS project has no direct impact on the configuration of ITOC, MPI also

has a major internal project to further develop its capability to analyse data to inform

several of its risk management processes and this may yet impact.

Released

Part One: Summary Observations/Conclusions

35. Customs developed the NTC and later ITOC over a decade, principally for their own

business improvement (effectiveness and efficiency) reasons. The costs were borne

by Customs.

36. Customs also saw NTC/ITOC in a wider border sector context where outcomes (public

safety and trade facilitation) and outputs (security risk management and related

Page 13 of 32

protection or control operations) were increasingly interdependent between agencies

and therefore required enhanced interoperability.

37. Customs always saw itself as the hub agency for the border sector. This arises not

only from the fact that it is the only agency with border management as its sole and

central statutory mission but also from the reality that the Customs systems have

provided core elements of the systems architecture for border management. Other

partners and stakeholders “orbited” around Customs. It therefore expected to lead the

way, in the sense of having to prepare Customs’ infrastructure and systems for other

agencies to connect with in order to enable deeper interoperability. In this context, the

expression “build it and they will come” was used by some Customs staff recalling the

NTC/ITOC planning phases.

1982

38. Customs had also expected that the fact of co-location would, over time, stimulate

recognition that integrated targeting was both necessary and technically feasible.

Act

Common doctrine and practice standards would evolve. At the time it was not as clear

as it is now that this does not apply end-to-end but to some parts of the targeting

continuum than in others.

39. In Customs’ planning for both NTC and ITOC, the gaps and obstacles to systems

integration, full knowledge fusion, centralised risk management and the various

constraints to functional interoperability were directly acknowledged. The need for

intelligence sharing for risk recognition (not threat response activation) – that is,

Information

strategic (not tactical) intelligence reporting collated and disseminated within the sector

and beyond to key partners (such as the Police) – was one such gap identified.

40. The need for an authorising and mandating process to further align systems,

Official

intervention doctrines and enforcement practices – through a “border accord” by

border sector governance leadership – was foreshadowed.

the

41. The establishment of BSGG and the subsequent promulgation of the 2008-13 Strategy

and work programmes appeared to meet this purpose. The strategy sets a goal of a

“more integrated and responsive border management system”. The targeting function,

primarily under the ‘protection’ work stream (refer

Figure 1) was to be a specific point

under

of focus. Customs NTC/ITOC plans were congruent with this.

42. It had, however, always been in Customs mind that the general tide of public

management doctrine in New Zealand, towards ‘joined-up’ government, with an

emphasis on sectoral and cross-sectoral outcomes, might, one day, carry the border

sector into a more defined hub and spokes architecture, or even to a unitary structure.

Released

This was a rational enough expectation, based on international comparisons. But the

2008-13 Strategy expressly ruled it out.

43. Other later machinery-of-government changes under the 2012 Better Public Services

reforms have somewhat taken border partners into other structural alignments – into

different sector configurations with different mission priorities.

44. The Reviewer does not intend this comment to be read as criticism of the decisions

that took Immigration NZ into an economic growth mega-agency (MBIE) and which

Page 14 of 32

tied Biosecurity NZ into an expanded primary industries mega-agency (MPI). They

were made by a different government from the one which owned the 2008-13 Strategy

and the economic (productivity) rationale especially in the immediate post-GFC context

(2008-11) was compelling. However, in the sense that all such acts have

consequences, one perhaps underappreciated consequence was that other pressures

and priorities besides border sector security interoperability came to the fore. At a time

of severe budget constraints, integrating border facilitation, and reducing compliance

for traders/tourists became the higher priority (e.g. JBMS Trade Single Window).

45. Furthermore the Strategy, spread across the three fields – Facilitation, Protection and

Partnerships – was intentionally incremental. In particular, it is not surprising that

progress towards knowledge fusion and integrated targeting has been incremental.

The obstacles to it foreseen by Customs – some extrinsic in nature – have persisted,

1982

and have constrained progress.

Act

46. The means by which the goals of the 2008-13 Strategy were to be achieved were

clearly not hard wiring but soft wiring – an “accord” based on collaboration, not

compulsion. Agencies retained their autonomous status; the border sector was a

confederation. Members would form “coalitions of the willing” and they were expected

to opt into resourcing the projects mandated by the BSGG as the programmes rolled

from design to implementation.

47. It is not clear whether the BSGG has formally reviewed progress and constraints

Information

across the Protection agenda as a whole, or in the subsidiary work programmes in

which enhanced targeting interoperability is a specified sectoral objective. Some

interviewees felt that ITOC had progressively become disconnected – “left to its own

devices” – from any wider sense of sector strategy and mission.

Official

48. The 2008-13 Strategy may have been overtaken or subsumed in other sector policy

documents or understandings, of which the Reviewer is unaware.

the

49. In any event, in a way the Strategy has lived on. There have been and are still efforts

towards its objectives at a sub-sectoral level, notably between Customs and MPI, in

the various components of the JBMS initiative.

under

50. Also, operational cohesion for border protection has been sustained, if not improved,

because of longstanding relationships and well-established practices for on-the-ground

collaboration, including between investigation and enforcement arms.

51. From a wider national security perspective, over the decade 2005-15, there do not

Released

appear to have been any major operational failures that could be traced back to

dysfunctionality of border sector response attributable to risk management or

knowledge management deficiencies. In fact, during this period there have been

several border security risk mitigation and threat management successes where cross-

sector collaboration was essential (for example, the Rugby World Cup). Sector

sensitivity to emergent risk and readiness also appear to have been well maintained

through exercising (for example, people-smuggling / mass arrivals).

Page 15 of 32

link to page 16

52. In addition, for some border agencies/partners, 2008-15 has been a time of heightened

alert or high operational tempo (for example, biosecurity issues) necessitating focus on

their core business, their business models and their support systems.

53. And it appears that all the core border agencies – and other collaborating agency

partners – have still managed to find resources to make certain capability investments.

So in terms of aggregate border readiness, and protection and facilitation capabilities,

it could also be said that national security may well have been improved.

54. Whether the various bespoke and agency-dedicated systems and tools fully

complement and reinforce each other or simply duplicate and whether a more

coordinated sectoral approach to capability might have further enhanced the sector’s

systemic capability are questions beyond the scope of this review.

1982

55. It is pretty clear, however, that the need for ITOC to provide capabilities which others

Act

did not possess a decade ago, particularly for operational coordination and crisis

management, has been much reduced.

56. This leads the Reviewer to conclude that overall sector governance (and indeed other

governance, for example, ODESC) have perhaps “left well alone” the border sector. It

has generally been seen as functional. It had its strategy and knew the Government’s

priorities, its evolutionary systems developments were a work-in-progress and its

operational performance overall was satisfactory. The saying “if it ain’t broke, it

Information

doesn`t require fixing” is true – up to a point.

57. It may, nonetheless, be time for BSGG undertake a strategy refresh and reaffirm the

importance of agencies leaning towards not away from the 2008-13 Strategy agenda

Official

of systems harmonisation and alignment. It can be argued, consistent with the

direction of the all hazards national security framework, that because the risk-scape

will continue to change and perhaps grow more complex, a wider range of border

the

effects will be required to meet a widening span of sectoral and cross-sectoral needs.

Therefore, agency systems will need to work ever more inter-operatively and across

the sector not just for tactical reasons but also if they are to emerge eventually as the

“one border management system” ordained by the 2008-13 Strategy.

under

58. The sector architecture itself also deserves some consideration. As it stands it is a

federated / loosely affiliated structure comprised of largely separate services which

interoperate to achieve border security/facilitation effects, in the same way that the

service arms of the New Zealand Defence Force interoperate (but there is no

comparable central command and no joint headquarters).

2

Released

59. A refresh led by BSGG could therefore ask if the sector`s evolutionary progress is

visibly towards highest interoperability at the points of highest interdependency where

risk management might otherwise fail.

2 Australia`s institutional architecture for border management reflects a different approach to border sector

integration from New Zealand’s. It has taken the structural path, amalgamating Customs and Immigration into

a single department (Department of Immigration and Border Protection) and also bringing previously separate

operations into one force (Australian Border Force) under one command. This resulted in integration of

targeting and operations in respect of all the non-biosecurity components of border protection. A further

summary is at Annex C.

Page 16 of 32

60. As for the 2008-13 Strategy systems integration agenda, the path itself may not have

changed; shared knowledge, aligned doctrine and harmonised practices (“no silos

within sectors”). A refresh might establish what has happened through or without the

work programmes and it could seek a consolidated picture of present and future

capability investment intentions.

61. A refresh should also look closely at the ‘protection’ work stream (refer

Figure 1) of the

2008-13 Strategy. It should ask what was intended in the “intelligence/risk profiling”

programme particularly in light of what is now known of the potential of automated data

analysis.

62. Specifically for Customs, a refresh needs to deliver some clarity about the future

sectoral value proposition of ITOC.

1982

Act

Information

Official

the

under

Released

Page 17 of 32

Part Two: Value Proposition

Post-Interview Key Points and Findings about Current Value

63. This section explores the question of present value on the basis of interviews and

responses to a questionnaire sent to the ITOC Governance Group agencies and some

of the partner/stakeholder entities identified in the 2008 BSGG terms-of-reference.

64. Customs itself is confident it is now getting most of what it wanted from ITOC. In

particular, it is getting results in terms of successful interdictions/seizures at the border

1982

from its investments in the targeting function, especially as its technical capabilities

have expanded around data analysis and smarter profiling tools. This is against a

backdrop of rising passenger volumes, rising cargo and mail volumes, and behavioural

Act

dynamics at vector or entity level. Customs shares with most New Zealand partner

agencies a particular sense of exposure to maritime border risks from craft and

passengers.

65. It has also become possible for Customs to achieve a higher degree of functional

alignment between intelligence and targeting – a situation it had been seeking since

the review of its IP&C Group – and ITOC is integral to this.

Information

66. Some progress has been made towards the wider sectoral goal – border protection

intelligence de-compartmentalisation – but the same systemic inhibitions about

privacy, information sharing and operational security that have affected other sectors

dog the border sector. ITOC has not become the centre of an interagency fusion

Official

function. In some respects, in fact, intra-sectoral accesses may have become more

constrained.

the

67. ITOC has become a recognisable “front-of-shop” for Customs externally. Overseas

partners can approach or be approached through ITOC. Whereas Customs values

ITOC as a reliable clearing house for its various offshore partnerships and regional

under

connections, other agencies do not see it as a collective facility representing the

international face of the New Zealand border sector. Agencies largely conduct their

own business bilaterally with counterparts.

68. An interesting observation was made, separately by two senior officials, about the

extent to which border management doctrine itself is shifting internationally towards

Released

balancing the traditional vector-specific risk management model (that is, single

movements of sea cargo/vessels, air cargo or passengers) with an entities-based

approach which spans all vectors and focuses on persons and cohorts with the

capability and intent to exploit border controls. This reflects strategic determination to

manage risk earlier – pre-border, not at border – and it may not apply equally to all

national circumstances. But it is a matter for consideration whether more pre-border

offshore collaborations of a multiagency nature are likely and should be explicitly

recognised as a future management challenge in the New Zealand context.

Page 18 of 32

69. If so, it may impact on ITOC`s future usefulness. It appears that there is presently no

institutional coordination point for the offshore engagements for the border sector as a

sector. That degree of agency autonomy in border sector diplomacy may well have

been, and may still be, quite appropriate for policy, information exchanges and even

political consent and assurance matters. But interviewees asked whether is it so for

the more complex operational matters that will inevitably arise with agencies

expanding both the range of overseas partnerships (for example, to cope with a

deeper internationalisation of organised crime) and the depth of offshore pre-border

operational engagement required to be effective in deterring or disrupting threats.

ITOC itself, in terms of its present form, may not be the answer to this question, but it

could be part of a functional solution if this were seen as a new strategic area for

systems integration.

1982

70. The present group of border sector partners – those with a presence at ITOC – held

views on a spectrum of mildly positive to rather negative about ITOC`s value to their

Act

agencies. The MPI group is the largest; it is made up of tactical intelligence analysts,

data analysts and target evaluators. Other agencies have, or have had, a one or two

person liaison presence. Some saw their interests better served by repatriating their

co-located staff, who appear to feel that the tasks being carried out were for their

parent agency, not the border sector. The greater benefit has been perceived in

stronger internal alignment and such external interfaces as were necessary with

Customs, or other partners, could be managed virtually. For some, the CBD location of

Information

ITOC was problematic because their efficiency gains came from frequent and easy

interaction between frontline staff and “their own” targeting specialists. The idea of

improving this situation by having an ITOC satellite facility at Auckland and

Christchurch airports received some support.

Official

71. Those partners closest to ITOC`s day to day business expressed misgivings about

culture and working environment. Some issues (incidents) have arisen involving

the

partner staff where accommodations amongst partner agencies have not been able to

be found and matters have escalated. There are feelings of marginalisation. Customs

acknowledges that there is some foundation for these attitudes and wants the new

cross-agency “governance” group to support its management, and guide it to effective

under

solutions to future matters of this kind. This is a sensible and overdue development.

72. The Reviewer wonders, however, because these are in many respects matters of

“feel” and “touch” regarding the working environment, it would be better to mandate the

group in a “management advisory” rather than classic governance role – expected and

entitled to be called upon, and consulted by management, contribute in a hands-on

Released

way to issue-management with practical solutions and carry their parent agencies

along with such solutions.

73. The senior interviewees from partner agencies were also aware of these matters, but

were less inclined to see them as devaluing ITOC itself. They generally felt ITOC had

bought efficiencies to Customs from which sector agencies benefited indirectly but as

a sector fusion centre and a sector communications and operations hub, it was an idea

whose time had not come or had passed (“things have moved on”).

Page 19 of 32

74. But they still saw some potential in reaffirming or renewing a sense of common

direction about border security risk management, better sectoral information sharing

and in continuing to treat targeting as a function with elements which are amenable to

very close, if not fully integrated practices, by border agencies.

75. The vast majority of Customs’ border protection activities are ‘routine’ and are carried

out by the relevant teams. They often require some bilateral collaboration between

agencies’ frontline team leaders, but do not require significant ITOC involvement. By

the same token, Customs’ own experience is that, in these cases, if called upon (for

example, at times of very high tempo) ITOC can supply planning and logistics inputs of

a high professional standard.

76. When Customs has the lead agency role in ‘deliberate’ operations of significant scale

1982

and complexity, involving other agencies, it relies on ITOC support. Other agencies,

notably Police and MPI, tend to use their own centres for tactical command and handle

Act

strategic oversight from their Wellington facilities close to the national security

apparatus run by DPMC. There are successful examples of the use of ITOC by lead

agencies other than Customs for joint operations where the delivery of effects at the

frontline/border are a big part of the tactical plan.

77. ITOC is capable of providing facilities for cross-agency crisis management in a

national civil emergency response, as it did for Customs in the Christchurch

earthquake, or in a wider event with international or regional actors. Many interviewees

Information

acknowledged that ITOC has such a contingency value, especially in Auckland.

78. A question asked by interviewees concerned the relationship between the National

Maritime Coordination Centre (NMCC) and ITOC particularly in regard to the fusion of

Official

sector information to create a common operating picture. NMCC is differently

governed. It is under its own CEO sector configuration (the Maritime Security

Oversight Committee not BSGG), is hosted by Customs but co-located with NZDF,

the

and has a formalised multiagency character, charter and mission.

79. That mission, leaving aside the rationing of maritime patrol assets for civil stewardship,

sovereignty and regulatory enforcement operations, is to support New Zealand

under

maritime domain awareness of physical activities and vessel/craft presences inside the

county’s Exclusive Economic Zone and beyond in the high seas approaches to it.

ITOC is a user of the NMCC`s current geospatial picture, which is multiagency-

sourced and fused up to a point defined by information security boundaries.

80. ITOC likewise produces for Customs a multi-layered picture of its operations onshore

Released

and offshore, maritime and aviation, more akin to that developed by NZDF. Other

border sector agencies and border entities have been developing similar capabilities,

as has Police.

81. But interviewees noted the absence of anything approaching a comprehensive holistic

multiagency security risk/threat awareness product for the maritime border

(passengers, crew and craft) – in contrast to the aviation border. There appears to be

room for some forward thinking in the border sector community about whether this is a

significant knowledge and systems gap. Some particular concerns exist about visits by

Page 20 of 32

cruise ships. Regulatory agencies such as Maritime NZ have risk management (vessel

safety and environment) alerting information and mitigation duties to discharge in the

same locations as Customs and other maritime border protection agencies. Risk

assessment, threat recognition and operational de-confliction are interests in common

which can be serviced by shared knowledge.

Value Proposition

82. With regard to ITOC`s future value, the following propositions, which arise from the

conversations with agencies and their feedback to the questionnaire, could guide

BSGG and other sector discussion and analysis. There are six broad areas where

future border sector interests potentially align. Within each area there are specific

1982

tasks and functions which appear multiagency in nature and which could involve ITOC

itself or the capabilities it houses. The future institutional shape of ITOC and its

Act

organisational configuration should be determined by decisions about future tasks and

functions. An evaluation of these propositions should involve testing for overall impact

in the wider context of border sector strategies and future developmental priorities.

Offshore arrangements and event-specific domestic operational coordination:

• Overseas partner arrangements and messaging – for pre-border operations

offshore involving more than one agency at either end and for Pacific regional

Information

support.

• Established, known, 24/7 accredited contact point and clearing house for

counterpart National Targeting Centres.

Official

• Large scale operational coordination and headquarters element capability for

certain domestic cross-agency operations (deliberate and responsive), and for

the

exercising.

• Profiling/Targeting capability for wider national security risk evaluation (including in

response to the risk shift to departures).

under

• Secure functionality for Customs or multi-agency use if business continuity fails at

other locations (for example, Auckland airport) or as ops/crisis centre for civil

defence and emergency management purposes.

Maritime border knowledge management – awareness and coordination:

•

Released

There is an opportunity, leveraging the NMCC and multiple agencies, to develop a

joint technology platform (geographic information system based common operating

picture) in support of the border sector responsibility to manage maritime border

security holistically and direct border risk responses. This would ensure the NMCC

knowledge product for maintaining maritime awareness and asset tasking and

coordination compliments ITOC’s product which is aimed at border response

planning and coordination functions.

• A stronger planning, coordination and de-confliction capability – covering small craft

arrival and departure season, cruise industry, maritime operations, risk vessels and

Page 21 of 32

maritime events – appears needed, and would be best enabled by a holistic

knowledge product.

• It would first require obstacles to secure information management and

communications functionality for multi-agency use to be addressed.

• Interested ITOC parties include: Customs, MPI, Immigration (and MBIE – offshore

oil industry), Maritime NZ and Police. Additional interested parties could include the

Environmental Protection Agency, the Ministry of Health, NMCC and NZDF.

Maritime targeting:

• A broader and better consolidated maritime border risk targeting process covering

commercial vessels (cargo, fishing, cruise) the small craft arrival and departure

1982

season, the cruise industry (passengers and crew), and safety and environmental

risk vessels.

Act

• Interested ITOC parties include: Customs, MPI, Immigration (and MBIE – offshore

oil industry), Maritime NZ and Police. Additional interested parties could include the

Environmental Protection Agency, the Ministry of Health, NMCC and NZDF.

Joint target analysis and development:

• It is considered that both data analytics capabilities and certain target development

Information

capabilities are inherently quite interoperable across the sector.

• There is commonality between the tools and techniques used to analyse and exploit

data and information.

Official

• The convergence of data and information streams, including that already underway

through JBMS, can be taken further to a wider group of border security risk

the

managers.

• It is increasingly well understood that the greatest convergences lie at the front end

of the target develop processes – i.e. data analysis (refer Figure 2).

under

• The efficiency and effectiveness benefits of closer targeting alignment, which

accrue with practice, are available to a wider group of border security risk managing

partners without compromise to operational specialisations.

• The means of achieving closer alignment and higher interoperability in these

particular functions maybe by co-location but certainly involve close engagement

Released

regarding doctrine and principles of collaboration best captured in an integrated

team approach.

• Different risk profiles and different vectors necessitate divergent threat management

and response practice. Tactical level target evaluation and selection is not a

function that lends itself to integration (as much as the data analytics and target

development functions and methodologies above do). But it still requires

accessibility, communication and other coordination arrangements amongst

agencies to support border security outcomes.

Page 22 of 32

link to page 23

• Intelligence enriches the process at two levels – strategic and tactical. There is a

need for a ‘border sector emerging risk’ identification capability and a strategic

knowledge product, generated by sector members and other contributors, and

commonly available.

3 It would be a holistic product joining vector and entity-based

approaches and analytics. BSGG and DPMC (SIB) would need to engage to

establish viability and mandate the arrangements.

ITOC configuration:

• ITOC performs for Customs a range of functions consistent with its title. But it is not

a facility which conducts sector-wide targeting or integrated operational

coordination. Based on the primary function of ITOC being the support of Customs

activities, Customs should therefore control ITOC.

1982

• Depending on the response of the BSGG to this review, the facility itself might in

future become the hub for a multi-agency targeting function focused on the

Act

elements of this process which have the greatest commonality in their practice (in

particular data analytics and target development – as outlined above).

• The targeting function could be configured as follows:

− Rotating manager responsible for process alignment and approach, tools and

capability development, relationship management and conduct.

Information

− Embedded agency representatives in a taskforce type approach.

− Team members report to their substantive agency for ‘pay and rations’ and retain

agency risk focus and profile development but utilising joint doctrine and

methodologies.

Official

− If so, it could be described as a team (or taskforce) housed within ITOC and be

separately named (for example, a Border Targeting Team).

the

• If other aspects of the future value propositions put forward above are adopted, the

sector functions to be performed should be carefully scoped and determined by

interagency agreement and those to be undertaken within a border targeting team

under

be the subject of a new charter.

• One consideration is the development of an airport based hub for border agency

targeting and evaluation staff to base themselves in either a permanent presence in

support of frontline staff or as an extension of the CBD based ITOC environment.

Overall impact – border sector mission and indicative development goals:

Released

• Apart from the joint targeting function proposed above, the remainder of the future

value propositions, whilst largely pointing at an interagency entity, only make sense

in the wider context of border sector mission and underlying developmental

direction. It is for BSGG to reaffirm the 2008-13 Strategy in that respect, or adapt it

by re-specifying as border sector collaboration goals, functional developments

which recognise interdependencies and support interoperability enhancements for

3 A sector product (the “Strategic Border Risk Assessment”) was developed. It is not currently being produced.

This may be related to wider intelligence community concerns and issues.

Page 23 of 32

agencies and partners with shared risk management responsibilities. However, in

order to make this document coherent to itself, the Reviewer has taken the liberty of

providing below an indication of what these refreshed or adjusted sector goals

might be. Adapted in part from recent Australian policy documents (see Annex C),

they are presented as outcomes and border security benefits:

− Improved ability to identify latent and hidden risks (strategic knowledge).

− Increased confidence about discerning levels of risk and prioritisation of

treatment.

− Earlier analysis of risk reduction and threat mitigation options (enables pre-

border responses).

− Earlier and richer quality threat-alert / watch list information to core sector

1982

agencies and partner/stakeholders.

−

Act

Analysis based on ‘one border’ (not single stream) and ‘entity plus vector’ to

enable more effective treatment of cross-cutting risks (e.g. maritime).

− Deeper international collaboration.

Information

Official

the

under

Released

Page 24 of 32

Part Three: Conclusions, Recommendations and Suggestions

Conclusions

83. Over the decade of NTC / ITOC evolution (2005-15) the border sector has largely

coped with rising pressures to enable commerce and enhance security without

imposing excessive compliance costs. Trade facilitation performance has been

improved. At the same time no significant border protection failures attributable to

institutional incoherence or interagency dysfunctionality appear to have occurred.

1982

84. A strategic agenda of systems integration between sector agencies and entities has

delivered some planned results but decision making about capabilities appears to have

become driven more by rising agency portfolio pressures rather than by a sense of

Act

sector mission.

85. ITOC has progressively become more integral to Customs’ core business. Its

performance meets expectations.

86. ITOC has not met Customs’ expectation that it could evolve into a multiagency facility

and hub for integrated border security risk management and protection operations.

Information

87. Other agencies and entities which value highly their relationship with Customs,

question the value they derive from ITOC even though their costs are more opportunity

costs than fiscal.

Official

88. Those with past or present experience of staff located in ITOC, have reservations

about maintaining these deployments.

the

89. Some of the reservations derive from intrinsic factors, including quality of

management, the work environment and conduct of business at ITOC. Others are

extrinsic and systemic. Recent steps towards more participatory ITOC governance

should help resolve the former, but may not be sufficient for the latter.

under

90. Accordingly, it is necessary to distinguish between improving matters within ITOC,

which is a task for management, and recreating a sense of direction for border security

/ border protection, which is a sector governance matter and the role of the BSGG.

Released

Recommendations and Suggestions

91. The 2008-13 Border Sector Strategy, which emphasises convergence upon a “single

border management system” appears to be the only sectoral “roadmap” but its current

status is unclear and its work streams (especially in regard to protection), whilst still

apparently relevant, needs refreshment.

92. A BSGG strategy stocktake should explore those aspects of border security where

risks are becoming more complex and crosscutting; identify where risk management

Page 25 of 32

interdependencies are rising; and determine where correspondingly higher levels of

inter-sectoral or cross-sectoral interoperability are needed.

93. The stocktake should also focus on defining outcomes which can be enhanced by

deeper collaborations and function or process convergences delivering recognisable

benefits.

94. The stocktake should inform and guide discussion and decisions about ITOC’s future

value proposition.

95. In particular, BSGG should form a view on data analysis and target development as a

common sector function, on the merits of a co-located sector-serving data analysis

capability and on its institutional shape and relationship to ITOC.

1982

96. Pending that, Customs should not take decisions about ITOC`s future management,

location, configuration or capabilities which assume continuity of interagency

Act

participation along present lines.

Information

Official

the

under

Released

Page 26 of 32

Annex A: ITOC Prehistory and Timeline

1989

A review by Gerald Hensley (‘A Structure for Border Control in NZ”) advocates

a structural merger to create a single border agency.

1990s

Customs builds a single integrated data base (‘CUSMOD”) with automated

capability to collect and analyse in real-time information from across its

various specialised outputs; underpins new operating model based on

applying risk management principles.

1999

The Border Services Review (“The Efficient and Effective Management of

1982

Border Services”) explores non-structural options for common or joint service

delivery.

Act

2000

Asylum-seeking phenomenon (unauthorised refugee movements by air and

sea) trending upwards internationally and affecting Australia (unauthorised

boat arrivals spike from 200 in 1998 to 3721 a year later). “Tampa” incident

occurred in August 2001.

2000

NZ immigration, education and tourism policy settings change – rising

onwards

numbers of authorised people movements across the border. New trade

agreements require Customs to offer faster assurance services (rules-of-origin

Information

validations) to goods traders. Wider range of source countries.

2001

Following the 9/11 attack in New York and related terrorist events in Europe

and East Asia, border security and security risk management became far

more intense. The US in particular raised new assurance requirements for air

Official

and sea movements of goods and people. Globalised financial flows and

internet-based communications were creating new pressures on border

security in regard to it targets, both traditional (e.g. drugs) and expanding (e.g.

the

people trafficking) for organised crime.

2002

The National Maritime Coordination Centre (NMCC) was established by

Cabinet (part of civ/mil review – Maritime Patrol capability and later “Project

under

Protector”). The NMCC to be standalone (operationally independent), club

funded, collocated with NZDF (JFHQ-Trentham) but hosted by Customs.

2005

Customs commences a major structural review – “Project Guardian”. Decision

to realign work streams to form a central Intelligence, Planning and

Coordination Group (IP&C).

Released

2006

A new National Targeting Centre (NTC) based at Mangere was established.

(June)

2006-07

SSC Review sector governance (not structural). Recommends new CEO level

sector governance group (BSGG).

2007

Cabinet considers the review; rejects single border agency, endorses a

(April)

collaborative approach by autonomous agencies aimed at a single border

management system.

Page 27 of 32

2007

Cabinet approves new governance and strategic work programme; TOR for

(October)

BSGG promulgated 17 Oct 2007.

2007

ODESC review; NMCC funding and administrative accountabilities shift to

Customs.

2008

BSGG issues a five year Border Sector Strategy.

(July)

2008

Election and change of government.

2009

Smartgate (facial recognition for air passenger processing).

2009-10

IP&C review by Customs CEO/SLT. ITOC proposal scoped and project

1982

development approved (March). Relocation to Auckland CBD from Mangere

set for December 2010.

Act

2011

Ministry for Primary Industries established by departmental amalgamation.

(July)

2011

ITOC operations commence at CBD location. Officially opened by the PM in

September.

2011-12

ATS-G, an advanced passenger screening/profiling tool (originally provided to

Customs by US for RWC) fully deployed.

Information

2012

MBIE (includes Immigration NZ) established by departmental amalgamation.

(July)

2013

Joint Border Management System and Trade Single Window Project.

Official

MPI/Customs common IT platform/shared services for import/export of goods.

Also changes in internal workflow management and investment planned for

new risk assessment and intelligence tools –“R&I” programme (funded under

the

BPS).

2014

IP&C group restructured to incorporate investigations and response functions

becoming Intelligence, Investigations and Enforcement (II&E). ITOC presently

under

belongs to this group.

Released

Page 28 of 32

Annex B: Terms of Reference and List of Agencies Consulted

ITOC Review: Terms of Reference

Purpose

1.

The Integrated Targeting and Operations Centre (ITOC) was designed to bring

together multiple agencies in one location to better facilitate the targeting and

treatment of risks presented to New Zealand’s border.

2.

The purpose of this review is to identify and report on the operational effectiveness of

1982

the ITOC and, capitalising on the work done to date, determine what next steps are

needed to ensure ITOC remains fit for purpose and of value to the partner agencies.

Act

Background

3.

The ITOC was officially opened by the Prime Minister on 02 September 2011 and has

continued to evolve and develop since this time.

4.

The ITOC was designed to bring together multiple agencies in one location to better

facilitate the targeting and treatment of risks presented to New Zealand’s borders. Co-

locating the targeting and operational planning and coordination functions should

Information

improve the capability to assess threats and to target risks to the border, and respond

to these more effectively and efficiently. The ITOC is also responsible for maintaining

an awareness of daily activity at the border, providing a 24x7 communications hub and

providing support to operational activity as required.

Official

Situation

5.

The ITOC has been operational in its current state for over four years and over this

the

time the number of partner agencies has increased. It is appropriate that the use and

operational effectiveness of the centre is reviewed. A review should provide the

opportunity for the ITOC partner agencies to increase the level collaboration and

coordination to maximise the benefits for all partners. This review also provides an

under

opportunity to identify potential overlaps or duplication in similar government agencies.

Objectives

6.

The review should address the following points and make recommendations:

a. Consider the original purpose and objectives of the ITOC and determine whether

Released

these are being met;

b. Assess how the ITOC reflects or integrates with the current and emerging

strategic priorities of partner agencies;

c. Determine if there are impediments to the efficient and effective operation of the

ITOC;

d. Determine the level of effectiveness of the ITOC’s resources and capabilities,

including potential performance measures, to inform partner agency investment in

the future;

Page 29 of 32

e. Consider the future purpose and role of the ITOC – ‘where to next’;

f. Consider how the governance, organisational arrangements, policies and

procedures of the ITOC could be improved to better serve the border sector and

related regulatory, law enforcement and security needs and requirements;

g. Consider the alignment of the ITOC with the National Security System and with

other joint intelligence, targeting and coordination centres, including the National