Cover sheet

Cover sheet

Paper submission to SDLT, National

Manager or Region Manager meeting

1. Subject

Subject/Title:

SDLT IMT Framework

Author

Paul Turner, National Manager Response Capability

Response required by

(date):

To be presented at

SDLT Monthly

(specify meeting type

and date):

2. Why is this paper being submitted to SDLT, National Managers or Region Managers

Noting

Approval

✓

Endorsement

✓

Discussion

Feedback

3. Sponsorship

It is the responsibility of the author to ensure that the paper being presented to SDLT, National Managers, or

Regions Managers is sponsored by a member of SDLT. Please tick the relevant SDLT sponsor(s):

✓ National Manager(s):

Paul Turner

✓

Training – SDLT portfolio holder

(David Guard)

✓ Region Manager(s):

Henderson, Grant, Guard

Equipment – SDLT portfolio holder

(Ron Devlin)

Districts - SDLT portfolio holder (Mike Grant)

Property – SDLT portfolio holder

(Paul Henderson)

Fleet - SDLT portfolio holder (Bruce Stubbs)

Chief Advisor DCE Service Delivery

Safety, Health and Wellbeing – SDLT portfolio

DCE Service Delivery

holder (Ron Devlin)

4. Consultation

under the Official Information Act 1982

The attached paper may have implications for other business groups, projects or programmes. It is the

responsibility of the author to ensure a proper consultative process has taken place beforehand. Consultation

has occurred with (please specify all relevant groups below, including teams within Service Delivery, other

internal business groups and external where appropriate):

Released

5. Comments

Advise below if there is additional information you would like SDLT/National Managers/Region Managers to

know when considering this paper. Advise what you are expecting to get from SDLT and/or the reasons why

this paper is being submitted to SDLT (if not covered in the body of the paper).

6. Recommendations

I recommend that SDLT

Note the summary of the current state of Incident Management in Fire and Emergency NZ.

Endorse the concept of developing an incident management system that may not explicitly name the base

operating system, but rather develop Fire and Emergency guidance documents based on ICS principles that

are compatible with ICS systems and aligned with AIIMS.

Endorse the concept of operations for incident management outlined in this paper.

Discuss the concept of using the EMPS system for accreditation for IMT roles not covered by the Fire and

Emergency Technical Competency Framework (TCF).

Endorse the development of Command and Control Guidance documents outlined in this paper (Incident

Management policy, Standard Operating Guidelines, Guideline Support Documents).

Endorse the progression of this capability.

Direct the National Manager Response Capability to seek funding to develop an indicative business case to

present to the Investment Panel to progress this capability.

7. Author sign-off

Name

Paul Turner

Title

National Manager Response

Capability

Signature

Date

10/08/2021

8. Business Owner/Manager sign-off

Name

Title

Signature

Date

under the Official Information Act 1982

9. SDLT sponsor sign-off

Name

Title

Signature

Date

Released

To: DCE Service Delivery & SDLT

From: Paul Turner, National Manager Response Capability

Date: 21 July 2021

Subject: Future IMT framework and transition to an ICS or AIIMS based command and

control system.

Reference #:

Purpose

The purpose of this paper is to outline the plan for Fire and Emergency to develop an integrated approach to

incident management, and to grow the incident management capability and capacity to a level that is

expected politically and publicly from the reformed organisation, and in a manner that is consistent with the

new organisational structure.

The paper will focus on identifying the current state, identifying what an integrated and unified approach to

incident management looks like, and outlining how we can progress this work.

Our Current State

Our current situation is that we have urban crews operating under the original Command & Control manual

and procedures based on CIMS1, and rural crews operating using ICS processes that they also use when

working on Australian and North American operations. A considerable portion of the internationally proven

and accepted ICS fundamentals and principles were lost in the re-writes of CIMS2 and CIMS3. (Teeling, Tony,

2017) (Teeling, Tony, 2017) (Cowan, 2017)

The current version of the Command and Control manual is based on CIMS 1 and hasn’t been updated since

it was introduced in 2007 and then amended in 2013. The NZFS developed a new manual based on CIMS2 in

2016, however this wasn’t introduced as it was decided that it wasn’t fit for purpose in terms of describing

rural operations. This was a significant gap given we were entering the transition phase to Fire and Emergency

NZ. Since that time NEMA has released the third version of CIMS [ CIMS3], which, as mentioned above, is a

further departure from ICS principles in terms of Incident Controller locations (ICS principle of one incident,

one IC, one IAP) and very NEMA and Planning centric at the cost of being Operations centric. Consequently,

Fire and Emergency has previously made the decision to move to the Australasian based AIIMS format of

incident management system. This format has been ICS based for several decades. However, recently the

under the Official Information Act 1982

National Commander has expressed reservations about Fire and Emergency explicitly describing our future

incident management system as AIIMS.

In terms of the organisation’s current capability; we have been operating successfully at an incident level

under the Interim Command and Control Policy (M1 POP) which was issued as a Fire and Emergency

Integration Day One policy, however the differences begin to show as the incident size or complexity

Released

increases, more so, when urban and rural crews are working alongside one another at the same incident.

The main areas of concern that have emerged since the Day One Command and Control policy was

introduced are:

• Fire and Emergency does not have an Incident Management system that reflects the new

organisational structure to provide a suitable incident management capability for large scale

incidents at the Region or National level

• Fire and Emergency does not have a planned; exercised; and documented system for all incident

types, and where personnel from different fire backgrounds are working together.

• Fire and Emergency does not currently have an incident management system that is competency

based, nor does it have a means of routinely, and regularly measuring that competence. It is

recognised that there is a technical competency framework under development but the organisation

is some way off in developing a competency assessment for all incident management team roles such

as Planning, Logistics, Intelligence etc.

• The current National Incident Management Team (NIMT) system provides a form of National level

management system, however the NIMTs are rural incident based, were designed to operate in an

environment when we had separate urban and rural jurisdictions, and therefore aren’t fully

compatible with the current Fire and Emergency organisational structures. As a result, the Region

Managers have expressed concerns and a desire to have a more direct relationship with the NIMTs

and how they are managed. Additionally, the activation processes do not reflect current Fire and

Emergency structures and will require some redevelopment of activation process and operating

plans

• National consistency is limited and there is limited awareness of national reporting requirements.

The NIMTs themselves lack consistency and there is a lack of compatibility between the NIMTs,

Region Coordination Centres, Region based IMTs, and the National Coordination Centre. Related to

this, there is only a limited understanding of the ICS co-ordination function, and the National Security

System Directorate coordinating functions. All of the above make it difficult for the Region Managers

and the National Commander to have clear oversight of a Region based or National based capability,

and to have a clear understanding of the organisation’s surge capacity capability

Identifying what an integrated or unified approach to incident management looks like.

As we integrate into a truly unified organisation, we need to develop policies, procedures and guidelines that

underpin incidents covered by our broader mandate inclusive of both rural and urban operations at ‘incident’

level, and at the higher IMT level in a consistent way. To do this we will develop incident management

structures that reflect Fire and Emergency’s new organisational structure with accountabilities at the Station,

District, Region, and National levels. We will write new Command & Control guidance that is consistent with

ICS based incident management principles. This will allow our operations to be managed under the same

standard operational guidelines with common terminology and structures, whilst still retaining the

interoperability with our international colleagues and sector partners.

To achieve this, we will follow the principles outlined below:

• Incident Management will be developed from the bottom up through Stations, District, Regions, and

then Nationally

• Maintenance of interoperability with other agencies for multi-agency events

• Carry out Incident Management based on Fire and Emergency Command and Control guidance

irrespective of incident type

• Establish Fire and Emergency NZ common terminology – but recognise differences between incident

under the Official Information Act 1982

types

• Ensure that competent personnel are in charge of Fire and Emergency NZ frontline appliances and

manage Level 1 incidents through existing qualification processes

• Fire and Emergency NZ will have a technical competency framework or an equivalent process for

accrediting personnel for Level 2 and Level 3 IMT roles (for example the AFAC Emergency

Management Professionalisation Scheme (EMPS) or an equivalent system

• Personnel managing Level 2 and Level 3 incidents will be assessed as competent to do so

Released

• Personnel performing IMT roles will be trained and assessed as competent to do so

• District and Regions may draw on non-frontline personnel from within Districts or Regions for IMT

roles

• Districts and Regions may draw on existing NIMT personnel for IMT roles

• Districts and Regions may use contractors or personnel from sector partners or other agencies (if

trained and accredited) for IMT roles

• Incident Controllers will be the person as assessed as competent for the role (dependant on

incident type), not the highest-ranking person

• Incident Controllers will only control incidents that they have the technical expertise to do so

The tables below detail the concept of building incident management capability up from incident level

through to level 3 regional or national incidents. The concept is that Level 1 incidents are managed with the

initial level response and monitored by Assistant Fire Commanders. Group Managers will be responsible for

incident management capability in their area of responsibility. The station level capability contributes to the

District Level 2 capability.

Level 2 incidents will be generally managed by Assistant Fire Commanders, supported by Officers from the

initial or greater alarm response, and supplemented by other executive officers (Assistant Fire Commanders

and Fire Commanders) from neighbouring Groups or Districts. District Managers will be responsible for

maintaining Level 2 incident management capability in their Districts. This capability may be supplemented

by personnel trained to fill specific AIIMS IMT roles such as PIM, Logistics etc. The District capability

contributes to the Region Level capability.

Level 3 incidents will be managed at a District or Regional level by personnel assessed as competent to

manage that type of Level 3 Incident and will be supported by personnel trained and assessed as competent

to fill IMT roles. Region Managers will be responsible for maintaining level 3 incident management capability

in their regions and ensuring that there is capacity available to respond to incidents. The Regional Level 3

capability will be drawn from District(s) Level 2 Capability within the Region and other personnel trained to

fill IMT roles. Initial response to Level 3 incidents will be drawn from within the Region capability, and

supported by other Regions, for larger or longer duration incidents. This is expected to be a formal and

planned approach to incident support, not an adhoc “on the day” arrangement. The combined Region

capability and capacity contributes to the National Capability.

Region resources may be drawn from the Region based NIMT personnel in the interim. Over time the current

NIMTs will be phased out as Regions develop their Level 3 capability creating greater depth and specialist

capabilities that will contribute to a National Capabilities.

National Level 3 incidents will be supported by all Regions and National Headquarters staff. Personnel can be

trained for IMT roles, or Coordination Centre roles, or both.

National Security or ODESC

System

National Response or

Coordination

under the Official Information Act 1982

Level 3: Regional

Level 2: District

Released

Level 1: Station Level

Accreditation of roles.

A fundamental requirement for any incident management system is to have people who are trained and

accredited to carry out their roles in the incident management team. Currently Fire and Emergency is

developing a Technical Competency Framework (TCF) to allow senior officers to demonstrate competency

for incident management, however this system is in it’s a development stage and is currently aimed at those

carrying the rank of Fire Commander and Assistant Fire Commander who would be most likely fill Incident

Controller or Operations roles.

An alternative to extending the TFC beyond the rank focus is the AFAC Emergency Management

Professionalisation Scheme. In 2015 AFAC developed an entity that could examine individuals involved in

emergency management education and experience and promote standards of ethics in the sector. The result

of this was the formation of the Emergency Management Professionalisation Scheme (EMPS) which provides

accreditation across all IMT functions as described in AIIMS at two levels, ‘Registered’, and the higher level

of ‘Certified’.

EMPS has been set up as a separate business area of AFAC under a Director who reports to the AFAC CEO,

who in turn is responsible to the AFAC Board and Council for the administration of the scheme. Currently it

is possible to gain registration for the following roles:

• Level 2 Incident Controller

• Level 3 Incident Controller

• Planning Officer

• Intelligence Officer

• Public Information Officer

• Level 2 Operations Officer

• Level 3 Operations Officer

• Logistics Officer

• Finance Officer

And the Certified roles are:

• Strategic Commander (for those in National Level Response Coordinator roles)

• Incident Controller

• Planning Officer

• Public Information Officers

• Operations Officer

• Logistics Officer

The scheme also offers registration and certification for a number of other roles beyond the IMT such as:

• Prescribed burning (Registered)

• Burn Controller (Certified)

• Divisional Commander (Registered)

• Fire Investigator (Registered and Certified) Fire and Emergency is engaged in the EMPS at this level

• Fire Behaviour Analyst (Registered and Certified)

under the Official Information Act 1982

• Arduous Bushfire Firefighter (Registered)

All accredited roles require a level Continuing Professional Development (CPD) which must be recorded with

the EMPS.

Although it makes sense to continue with the TCF to continue to assess the competency of the Fire and

Released

Emergency commander level ranks, consideration should be given to adopting the EMPS system of

accreditation for non–uniformed or ranked personnel (internal or external) who will be members of District

or Region based IMTs or Coordination Centre Teams.

More information on the scheme can be found a

t https://www.emps.org.au/

Details of Incident Management Capability Concepts

Level 1 Incidents.

Level 1 incidents are characterised by being resolved through the use of local or initial response

resources only. Control is limited to the immediate area and the Incident Controller usually performs all

the necessary functions. The Incident Controller may delegate some functions to personnel on scene

(e.g. operations managed by crew leader).

Group Managers are responsible for ensuring that there is incident management capability for Level 1

incidents within their Groups.

Managed at Incident / Station level. Assisted by Assistant Fire Commanders, stations from neighbouring

Groups, other Assistant Fire Commanders. Monitored by Group Manager / Assistant Fire Commander.

Controlled by

System / information

Accreditation levels

Notes

required

• Chief Fire Officers

Detailed knowledge of

Accredited through

General day to day

• Deputy Chief Fire

Fire and Emergency NZ

current qualification

incidents managed at

Officers

Command & Control

process.

station response level.

• Senior Station

guidance

May require Group

Officers

Incident level OICs

Manager response at

• Station Officers

Awareness and trained

(people in trucks) will

times to provide

• Voluntary Rural Fire in Fire and Emergency

maintain the same

additional control

Force Controllers

incident Command and

training and

measures or assist with

• Voluntary Rural Fire Control processes.

qualifications systems

coordinating specialist

Force Deputy

that they operate

response.

Controllers

Awareness of CIMS for

under in the short –

• Rural Fire Officers

multi-agency

medium term.

interaction.

Qualification processes

and systems reviewed

and updated over time.

TAPs systems need to

be modified to

incorporate new C&C

guidance and AIIMS

terminology

under the Official Information Act 1982

Released

Level 2 Incidents.

Level 2 incidents may be more complex either in size, resources or risk. They are characterised by the

need for:

• deployment of resources beyond initial response; or

• the operations being divided into geographic or functional sectors; or

• the establishment of incident management functional roles due to the levels of complexity; or

• a combination of the above.

District Managers are responsible for ensuring that there is incident management capability for Level 2

incidents within their Districts

Managed at Group Level. Assisted by neighbouring Assistant Fire Commanders, Stations from

neighbouring Groups or Districts. Monitored by District Manager / Fire Commander.

Controlled by

System / information

Suggested

Notes

required

Accreditation levels

• Initial OIC

Detailed knowledge of

Fire Commanders and

Requires Assistant Fire

• Assistant Fire

Fire and Emergency NZ

Assistant Fire

Commander response.

Commanders

Command & Control

Commanders:

Assistant Fire

• Fire Commanders

guidance.

Technical Competency

Commander will form

Framework (TCF)

IMT from initial

Detailed knowledge of

Level 2 Incident

response resources.

Fire and Emergency

Controllers

incident management

EMPS accredited IMT

May call for further

systems and command

roles

executives (Group or

and control processes

District) or other

specialists to form initial

Awareness of CIMS for

IMT.

inter-agency processes.

IMT relief may come

from other Districts or

Regions.

Coordinated (if required

at RCC level)

under the Official Information Act 1982

Released

Level 3 Incidents.

Level 3 incidents are characterised by degrees of complexity that may require a more substantial

organisational structure to manage the emergency. These emergencies will usually involve delegation of

all incident management functions.

Incidents which by their very nature provide a degree of complexity that requires the establishment of

divisions for the effective management of the situation. These incidents will generally involve the

delegation of all functions and the Incident Management Team (IMT) will have the majority of roles

filled.

• The IC will have designated a large number of functional roles

• The threat/impact to the community and/or environment will be large

• Incident Actions Plans will be written and likely detailed

• Regional or National resources will be required

• Numerous other agencies and stakeholders will likely be involved

Region Managers are responsible for ensuring that there is incident management capability for Level 3

Incidents within their Regions and to support National Deployments.

Managed at Region Level. Assisted by Neighbouring Group and District Managers, Stations from

neighbouring Groups, Districts or Regions. Inter-Region resources coordinated Nationally.

Controlled by

System / information

Suggested

Notes

required

Accreditation Levels

• Initial OIC

Detailed knowledge of Technical

Regions to maintain Level 3 IMT

• Assistant Fire

Fire and Emergency

Competency

resources for all of the AIIMS

Commanders

NZ Command &

Framework (TCF).

IMT functions to manage the

• Fire

Control guidance.

Level 2 and 3

initial response to a level 3

Commanders

Incident Controllers

incident.

• IMT drawn from Detailed knowledge of EMPS or similar

Regional

the Fire and

accredited IMT roles. IMT positions such as planning,

resources.

Emergency incident

logistics etc do not need to be

• Backed up by

management systems

filled by operational personnel,

IMT resources

and command and

but personnel must be trained

drawn from

control processes:

and accredited.

other Regions.

Completed Fire and

• Coordinated

Emergency NZ IMT

Regions will have ICs or

Nationally

training courses.

Operations Managers that have

Knowledge of CIMS for

incident specific expertise, for

under the Official Information Act 1982

inter-agency

example:

processes.

• Vegetation

• Complex structure fires

Knowledge of National

• Earthquake

Security / ODESC

• Flood / Weather events.

system for National

reporting

Released

Further resources / relief IMTs

drawn for other Regions.

Inter-Region response or relief

IMT resources coordinated

nationally through NCC

Regions to maintain personnel

trained to staff Region

Coordination Centres.

National

Inter – Region resources for Region

back up IMTs are coordinated

national y.

Requires Fire Commander

District

Region Managers are

and / or IMT response.

responsible for ensuring that IMTs formed by trained and Requires Assistant Fire

Regions have Level 3 IMT

Group / Station

accredited personnel for ICS

Commander response..

capability to assist inter-

based IMT roles.

Assistant Fire Commander wil

regionally.

form IMT from initial response

Incidents managed at station

Region Managers are

DCE Service Delivery ensures

resources.

level by crew OICs

responsible for ensuring that

that there is a national and

Other specialist IMT roles may be Some incidents require

there is Level 3 IMT capability required.

international capability.

Assistant Fire Commander

in their Regions.

response.

District Managers are

Fire Commanders or other

Group Managers responsible

responsible for ensuring that

personnel are trained and

Group Managers can fulfil

for ensuring incident

accredited to manage Level 3 response requirements within

management capability in

incidents.

their Districts.

their Groups (qualifications,

OSM etc)

Assistant Fire Commanderss are

qualified to manage incidents

and supplemented by people

trained to fill IMT roles.

The role of Coordination Centres.

The requirements, activation triggers and the role of the coordination centres is laid out in M1-4 POP

Coordination Centre Policy and M1-4 SOP Coordination Centre Procedure. However, during the Tasman fires

there was some criticism or questioning the role of the Region and National Coordination centres and a view

was expressed by some that the coordination centres added an element of confusion and interference as to

who was doing what.

There appears to be a cultural or operational difference between the different types of operations and use

of IMTs from the legacy organisations. This is because the previous Rural sector would tend to develop a fully

staffed or ‘deep’ IMT that needed little support beyond the IMT itself other than some oversite from their

home agency due to the fact that there was little national coordination amongst the various rural fire

under the Official Information Act 1982

authorities, whereas in the urban side of the business the IMTs have been quiet ‘thin’ due to the high speed

nature of the operations – and the coordination centres were leaned on heavily to support the business with

resources, shift changes, welfare etc. Additionally, the coordination centres in the urban side of the business

have been relied on to provide oversite for weather type incidents where we might have 40 – 50 individual

concurrent responses across multiple locations, with the resourcing and oversight being managed by a senior

officer in a coordination centre. Sometimes with NCC oversight if the weather event is moving down country,

or inter-regional resourcing is required.

Released

Furthermore, the organisation has responsibilities (managed by NCC) in terms of the National Security System

Directorate and the NCMC which a lot of people beyond the NHQ environment don’t currently have much

awareness of. These are all things that we need to look at and find the right balance as we progress this work.

However, it has been seen that having multiple coordination centres for one incident (regardless of size) does

not work and it may not be necessary to have both and RCC and an NCC activated for a single incident.

Recommendation 11 of the Tasman Fire Action Plan suggests that Fire and Emergency should review, clarify,

and document the roles of the NCC, RCC, and the IMT in Fire and Emergency managed incidents, to include

reporting lines for NIMTs, and the working relationships between field based and national based co-

ordination centres. This work can be captured as we develop and define this IMT framework.

What is the best incident management system for Fire and Emergency?

In July 2017 AFAC released the Independent Operational Review into the Port Hills fires of February 2017.

The review highlighted the issue that the Coordinated Incident Management System (CIMS) was less effective

in managing the incident as it had not used in a consistent manner between the various fire agencies. The

review went on to discuss the opportunity for Fire and Emergency to move to the Australasian Inter-Service

Incident Management System (AIIMS).

The reason for this conclusion is that Australia and New Zealand would be able to share ideas and

operate together on a common operating platform. AIIMS is an Australasian system supported by

AFAC, and all of the states in Australia and Fire and Emergency New Zealand already contribute to

AIIMS through its membership of AFAC. AIIMS has a well-resourced steering committee that supports

its development and is able to be updated based on worldwide best practices and experiences gained

through participation in overseas deployments. The system was developed to meet community needs

as well as the needs of the emergency services using it. Another advantage it offers for Fire and

Emergency New Zealand is that all the training material required to be competent in using the system

is included in the AIIMS package, and training material is updated as the system is reviewed.

Therefore, there is negligible cost for Fire and Emergency New Zealand in moving to AIIMS; as a new

organisation it presents a unique opportunity to support a unified organisation. (Goodwin, 2017)

Furthermore in 2019 the AFAC independent review of the Tasman fires recommended (Recommendation 9)

that Fire and Emergency New Zealand adopt AIIMS.

Fire and Emergency New Zealand should embed AIIMS as the preferred internal incident control

system for the management of its incidents. Personnel who interface outside of Fire and Emergency

New Zealand with one or more agencies including the broader emergency management

arrangements should retain an understanding of CIMS management structures and liaison and

reporting requirements so they can operate in that capacity when required. (Cooper, Considine,

Cartelle, & Papesch, 2019)

However, in the discussion leading to the recommendation they make the point that they were not

suggesting that CIMS was not fit for purpose and was recognisably related to AIIMS and the North American

ICS system (NIMS).

We are not suggesting in this discussion that CIMS is not fit for purpose and to the contrary, as noted

above, it is recognisably related to AIIMS and NIMS. Where we consider that AIIMS may add

significant value is that in its development over the past 20 years, it has been through a number of

under the Official Information Act 1982

revisions with significant input from operational experts going into each one. This has established it

as a rich resource for incident managers based on lessons identified, and significant research into the

practice of incident management. Another peripheral benefit of AIIMS is that as the ICS used by all

Australian fire and emergency service agencies, sound knowledge of AIIMS makes it easier to fit into

Australian incident management structures in the event of a deployment. (Cooper, Considine,

Cartelle, & Papesch, 2019)

Released

This raises a number of points to consider in determining what incident management system Fire and

Emergency should utilise when responding to the approximately 80,000 incidents per year when Fire and

Emergency is the lead agency. There is no doubt that Fire and Emergency will use CIMS when involved in

large scale multi-agency events as has been witnessed recently with responses to weather related events

such as the South Auckland tornado, or the Westport flood response, but what is required for Fire and

Emergency is an incident management system that details how Fire and Emergency will operate for when it

responds to the various incident types that we attend, and allows for supporting guidelines to be developed

for specific incident types such as hazardous substance, or high rise building fire incidents, as well as various

levels of wildfire incidents.

In doing this it may not be necessary to explicitly choose or name a system, but rather develop Fire and

Emergency guidance documents based on ICS principles that are compatible with ICS systems but with a

particular focus on aligning the guidance with AIIMS as this would give Fire and Emergency access to the full

suite of existing training resources produced at no cost by AFAC which will be a cost effective and expedient

option.

Development of new Fire and Emergency Command and Control guidance

Previous versions of the NZFS and Fire and Emergency Command and Control manuals have been prescriptive

in nature and in terms of their purpose because they contained not only Command and Control guidance,

but also material that better belonged in a training document.

It is suggested that the new guidance will provide Fire and Emergency Incident Controllers with a range of

command and control principles and options for incident management for any type of incident regardless of

level that Fire and Emergency might attend.

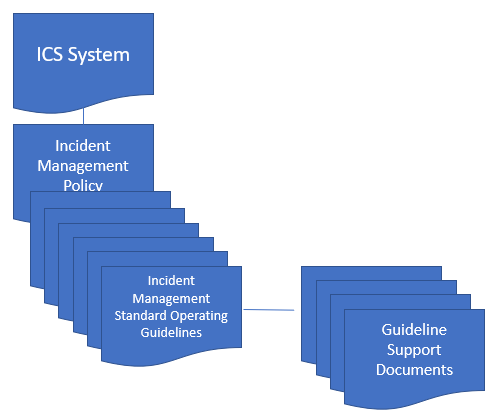

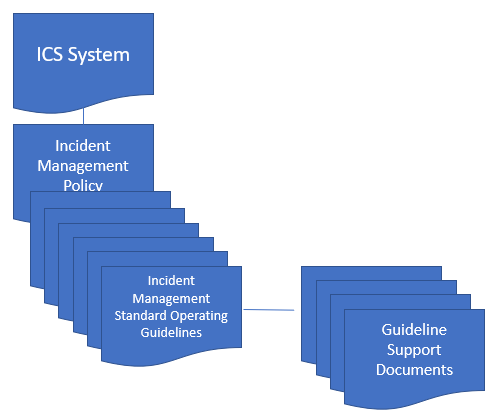

The plan is to have documents that follow a cascading structure with the chosen ICS system or principles as

the capstone document, followed by:

• An Incident Management Policy that describes:

o The purpose

o The scope and application

o Legal and policy framework

o Policy principles

o Policy implementation

o Roles and responsibilities

o Training and support for incident management

o Monitoring and review cycles

o Document control

• An Incident Management Standard Operational Guideline (SOG) that provides guidance on:

o Deployment

o Command and Control

o Situation evaluation

o Incident Action Planning

o Incident Communications

o Incident Structures

o Review and revision

under the Official Information Act 1982

o Escalation and de-escalation

o Incident safety

o A process based on the DEBRIS model that details how to manage:

▪ Decontamination

▪ Entry and exit of hot zones

▪ BA service areas

▪ Rehabilitation and monitoring of firefighters

Released

▪ Incident ground accountability of all personnel

▪ Staging areas for firefighters and appliances

• Guideline support documents which give detailed information on Incident Management, safety,

and any other topics, such as the decontamination processes, that support incident management

and can form the basis of training material.

The Command and Control Guidance:

The Command and Control Guidance:

• Is developed pursuant to the fundamentals of ICS

• Describes why guidance on operational incident management is more appropriate than prescriptive

“directives”, given that a prescriptive approach cannot account for the widely differing circumstances

of each incident

• Documents FENZ’s command and control doctrine, elaborating on the philosophies and

underpinning principles of ICS

• Clearly articulates the intent and application of relevant legislation

• Describes the base incident management roles that are applicable for all incidents

• Describes how an incident management structure is established and when and how it may be

required to be built on

under the Official Information Act 1982

• Establishes the incident management terminology to be used by FENZ

• Explains that both flexible and prescriptive approaches are key to effective incident management

teams, their structures, and their operational direction

• Explains how incident controllers can apply the guidance approach [see para on Training

Considerations below]

• Explains how personnel and the organisation can be legally protected when following a guidance,

Released

rather than prescriptive approach

• Establishes the means of incident management for all FENZ led incidents regardless of

o the type of incident

o the complexity of the incident

o the scale of the incident

o where the incident is located

o the seniority or rank or daytime role of the incident management team membership, and or

the personnel at their disposal; and

o what other agencies are in attendance or providing assistance.

• Clearly establishes the purpose of the incident management co-ordination function, and role of Co-

ordination Centres

• Recognises that the competency, skill, experience and professionalism of people are absolutely

essential for effective incident management, not just rank and seniority alone

• Makes reference to the capability and capacity requirements that are key to maintaining FENZ’s

incident management readiness

• Outlines how we dovetail into an emergency managed by any other agency who use CIMS as their

incident management platform

The Command and Control Guidance is not a document that:

• Should be applied in an exclusively prescriptive fashion

• Replaces incident management training notes and courses, operational policies, incident specific

SOG’s, and or other related SOG’s

• Determines rank, the application of ACL, and who should lead and or be members of incident

management teams

• Has separate urban and rural sections

• Should be rigidly adhered to when FENZ is not the lead agency

Training Considerations.

To manage the relatively short duration, high intensity type incidents that Fire and Emergency responds to

daily (approx. 80,000 per annum), we have in the past relied on prescriptive policies and procedures. The

further down the chain we go the more the prescriptive the procedures are. But we have also managed larger

scale incidents that we have not developed prescriptive procedures for (and will not be able to). These types

of incidents need to be managed by the ’Thinking Commander or Incident Controller” and to do this the shift

to a guidelines approach needs to be underpinned by a comprehensive programme of training, consolidation

and exercising for each individual role in the IMT. The majority of the training collateral for AIIMS IMT

positions is available to Fire and Emergency from AFAC for little or no cost, however, our Workforce

Capability Team will still need to be funded to coordinate and deliver the courses associated with each IMT

role, and to deliver a regular exercise programme to underpin the IMT skills. The People and Workforce

Capability Team will need to be included at every step of the process as this system is developed to ensure

that this work is planned for, budgeted, and accepted into the Training pipeline system.

Progressing the Capability.

To progress the full Fire and Emergency IMT capability programme will require a number of workstreams to

be set up. These workstreams can be defined further as the concept is developed but the following pieces of

work need to be captured: under the Official Information Act 1982

• Development of AIIMS or ICS consistent Command and Control guidance

• Development of a Command and Control Policy along with Standard Operational Guidelines (SOGs)

and Guideline Support Documents (GSDs)

• Awareness, implementation, and training rollout for the new Command and Control guidance

documents and SOGs

• Updating of the Training and Progression System (TAPS) and the Operational Skills Maintenance

Released

system (OSM) to reflect the new documents

• AIIMS or ICS based IMT training packages

• An accreditation system for Level 2 and Level 3 Incident Controllers (most likely the Technical

Competency Framework currently being developed)

• The phasing out of the National Incident Management Teams (NIMTs) as the Group, District, Region

capabilities are developed

• The development of the National Capability as the Region based IMTs are in place.

As a first step it is suggested that the following workstreams should be established:

• Command and Control Doctrine

o Development of manuals, Guidance, and Support documents

• Workforce Capability and Training

o Training and rollout of new Command and Control, and Guideline documents

o AIIMS or ICS consistent IMT training packages

o TAPS update

o Update of OSM skills

• Incident Management Structures

o Development of the Group, District, and Region IMT structures

o Phasing out of the NIMTs

• Accreditation or Technical Competency Framework

o Accreditation for Level 2 and 3 incident controllers

Conclusion

This document outlines the current state of Fire and Emergency’s incident management capability, discusses

what a unified incident management capability would look like for Fire and Emergency, and how we can

progress this capability development. As we develop into a truly unified organisation, we need to have an

incident management framework that is consistent with our newly implemented organisational structure

and is consistent with the organisations decision to use an AIIMS or ICS based system. This framework will

set the organisation up to be able to deploy the right people, with the right training and accreditation with

the right incident management system to any incident that Fire and Emergency people respond to.

The work needed to develop and introduce this enhancement to our broader responsiveness should not be

underestimated, nor should it be considered a “one off” action. There needs to be a commitment to ensuring

that once the desired levels of capability and capacity are reached, the same enthusiasm and rigour is applied

to sustaining it.

Recommendations

I recommend that SDLT:

Note the summary of the current state of Incident Management in Fire and Emergency NZ.

Endorse the concept of developing an incident management system that may not explicitly name the base

operating system, but rather develop Fire and Emergency guidance documents based on ICS principles that

are compatible with ICS systems and aligned with AIIMS.

under the Official Information Act 1982

Endorse the concept of operations for incident management outlined in this paper.

Discuss the concept of using the EMPS system for accreditation for IMT roles not covered by the Fire and

Emergency Technical Competency Framework (TCF).

Endorse the development of Command and Control Guidance documents outlined in this paper (Incident

Management policy, Standard Operating Guidelines, Guideline Support Documents).

Endorse the progression of this capability.

Released

Direct the National Manager Response Capability to seek funding to develop an indicative business case to

present to the Investment Panel to progress this capability.

Signed:

Name: Paul Turner

Job title: National Manager Response Capability

Bibliography

Cooper, N., Considine, P., Cartelle, B., & Papesch, D. (2019).

AFAC Independent Operational Review, A

review of the management of the Tasman fires of February 2019. Melbourne: Australasian Fire and

Emergency Service Authorities Council Limited.

Cowan, J. (2017).

Incident Management Systems avaialble for use in New Zealand. Cowan.

Goodwin, A. (2017).

INDEPENDENT OPERATIONAL REVIEW, Port Hills fires - February 2017. Melbourne:

Australasian fire and Emergency Service Authorities Council Limited.

Rooney, S. (2021).

A revised incident management platform for Fire and. Wanaka: Rooney.

Teeling, Tony. (2017).

CIMS _AIIMS comparison analysis 2017. Christchurch: Integrated Consultancy

Limited.

Teeling, Tony. (2017).

Differences between CIMS and AIIMS. Christchurch: Integrated Consultancy Services.

under the Official Information Act 1982

Released