3. Economic Impact Assessment

under the Official Information Act 1982

Released

© 2021 Deloitte Access Economics

17

SUMMARY

Overview

An economic impact assessment of the Three Waters Reform

The request

Overview of the economic impact of the reform

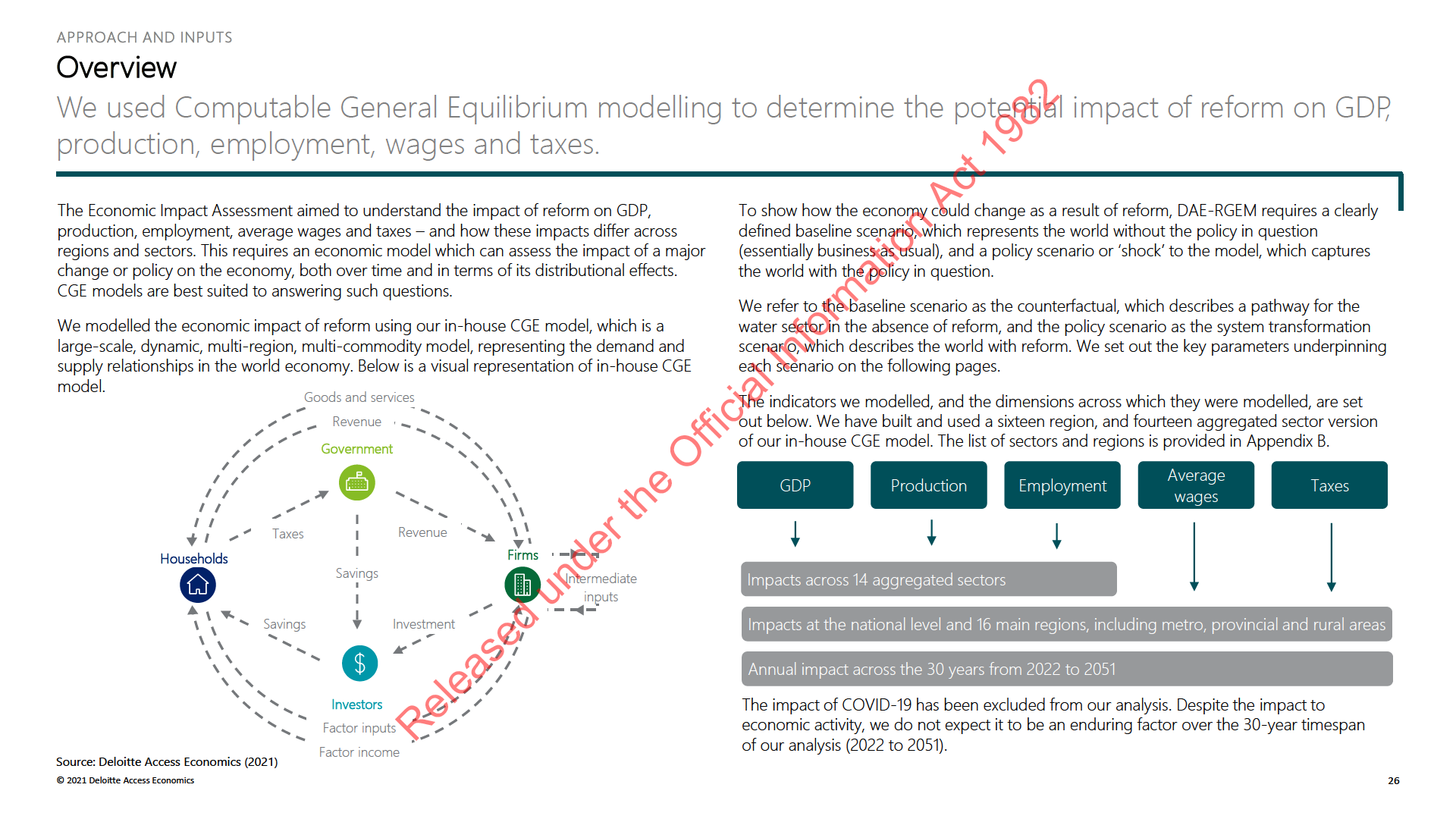

Deloitte Access Economics has been engaged by DIA to assess the potential economic

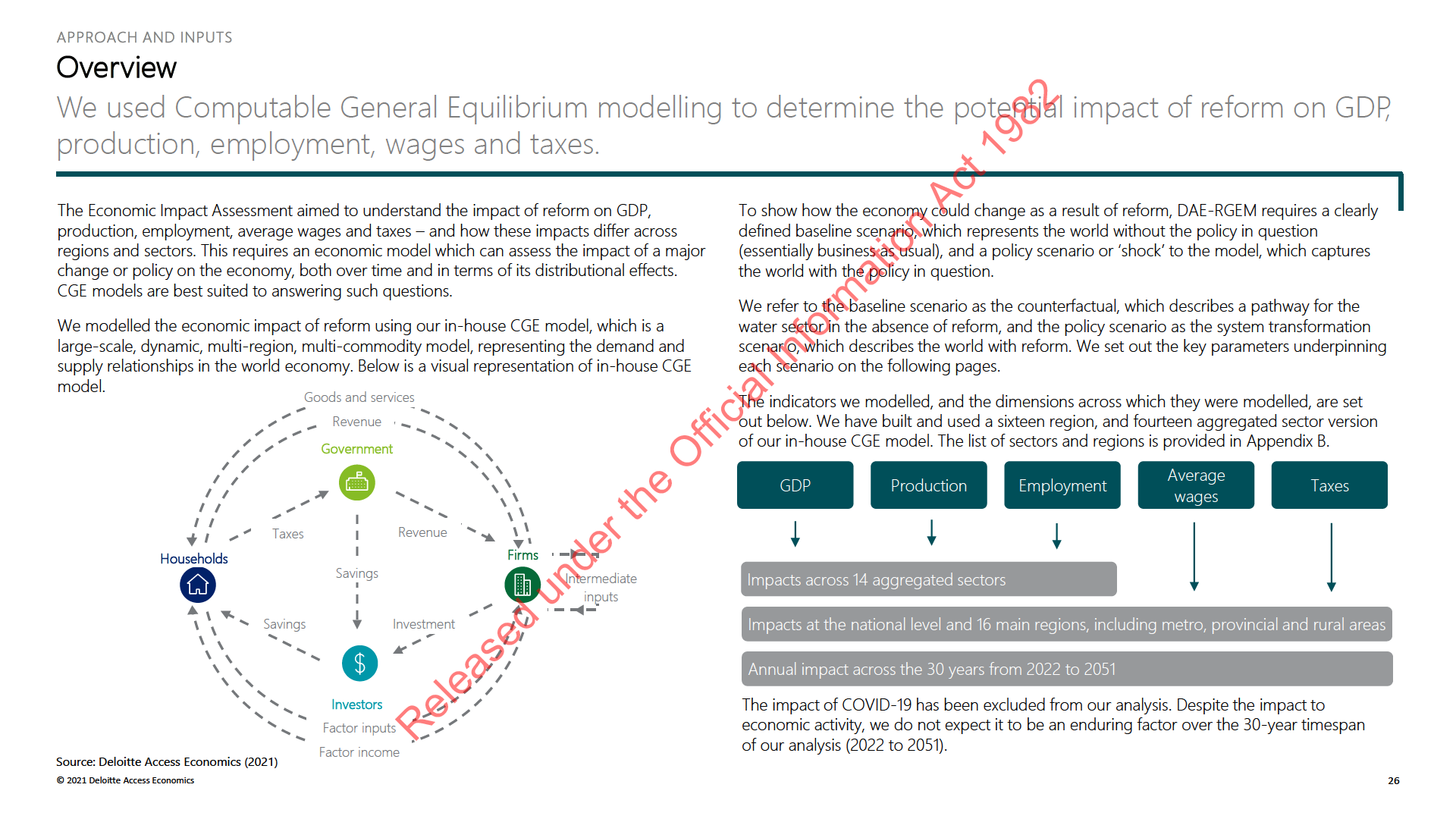

• Economic activity involves a range of complex interactions between households,

impact of the Three Waters reform, and to develop an understanding of the opportunities

businesses and governments with these agents operating across regions and countries. A

and risks presented to the affected industries. The economic impact assessment and

change in any part of the economy can therefore have a ripple effect throughout the

affected industries analysis will provide evidence to support the Regulatory Impact

whole economy. For example, a new project or program might create economic

Assessment (RIA).

opportunities in one region, but could also increase the scarcity of inputs, and in turn

affect output in other sectors.

This section of the report provides results for the economic impact of the reform. Deloitte

Access Economics assessed the economic impact of a material step up in investment in

• Computable General Equilibrium (CGE) models are the best-practice method available for

examining the impacts of a change in one part of the economy on the broader economy.

connection with reform, relative to the level of investment that might be expected in the

This is because CGE models explicitly account for behavioural responses of consumers,

absence of reform (i.e. the counterfactual). The assessment estimates how this would flow

firms, governments and foreigners, while evaluating the impacts of a given policy change.

through to national and regional indicators such as GDP, employment, wages and taxes.

At the same time, CGE modelling also accounts for resource constraints and effectively

Sections 10 to 17 discuss risks and opportunities for industries affected by reform.

represents the economic trade-offs that face the economy and its participants.

Structure of this section of the report

• The economic impact of the reform has been estimated using Deloitte Access Economics’

in-house Regional General Equilibrium Model (DAE-RGEM). More technical detail

This section presents the findings of economic impact assessment as follows:

regarding CGE modelling can be found in Appendix A. Economic impact modelling

• Overview of economic impact assessment

compares two future projections of the economy (scenarios) and compares the difference

• Scenario overview

between the two to estimate net impacts.

under the Official Information Act 1982

• Approach and inputs

The two scenarios are:

• National impacts

• Counterfactual: Under the counterfactual scenario, we assumed a pathway for the water

• Workforce impacts

sector in the absence of reform. This scenario draws on the expected investment profiles

• Distributional impacts

without reform over the 30 years from 2022 to 2051.

• System transformation: This scenario models the New Zealand economy with reform,

providing an illustrative range of the accelerated investment profile reform could enable

Released

relative to the counterfactual. This scenario factors in the expected investment profiles

under reform, over the 30 years from 2022 to 2051.

© 2021 Deloitte Access Economics

18

SUMMARY

Summary of results for core scenarios

Reform could deliver a significant economic benefit. Our focus in reporting the results are on the Low and

High Scenarios to provide an indicative range of the potential economy impact.

Our analysis focuses on Low Scenario and a High Scenario, as this provides a low and high range for the resulting economic impact. Each scenario contains high or low inputs for forward

investment profiles for the counterfactual and system transformation scenarios. The net economic impact for each scenario is presented below. We have used a 5% discount rate, per the New

Zealand Treasury’s default discount rate.*

A summary of the net economic impact relative to the counterfactual – 2022 to 2051. Change in:

Scenario

GDP

Production

Average FTEs

Average wages

Taxes

1. Low Scenario: Low system transformation vs low

constrained counterfactual

+$14b

+$29b

+5,849

+0.16%

+$4b

2. High Scenario: High system transformation vs

high counterfactual constrained

+$23b

+$47b

+9,260

+0.26%

+$6b

Source: Deloitte Access Economics (2021)

Definitions

GDP: Change in real Gross Domestic Product (GDP) in present value terms over the period 2022 to 2051. GDP includes value added and taxes.

Production: Value of the change in production in present value terms over the period 2022 to 2051. Production is the change in GDP plus the cha

under the Official Information Act 1982nge in intermediate outputs.

Average FTEs: Average change in full-time equivalent employees over the period 2022 to 2051.

Average wages: Percentage change in average annual wages as a result of reform, over the period 2022 to 2051.

Taxes: Value of the change in overall taxes, in present value terms, as a result of reform over the period 2022 to 2051.

*Using an Social Rate of Time Preference of 3.5%, under the Low Scenario, the GDP result is $18b, production is $36b and taxes are $4.4b. Under the High Scenario, the GDP result is $29b,

production is $58b, and taxes are $7.2b.

Released

© 2021 Deloitte Access Economics

19

SUMMARY

Summary of results for other modelled scenarios

The Optimistic and Historic Scenarios also show a large positive impact across the economy as a result of

reform.

We also modelled two other scenarios based on alternative assumption sets. The net economic impact of the other scenarios is shown below, again using a 5% discount rate. Neither of the two

scenarios below are included in our preferred core scenario range. We do not consider the Optimistic Scenario as likely, and as the Historic Scenario is based on historic capital spend rather than

a forward looking perspective, which we consider less relevant. The historic scenario provides a cross-check for what might happen if councils do not change historic behaviour in response to

increased regulatory and community pressure.

A summary of the net economic impact relative to the counterfactual – 2022 to 2051

Scenario

GDP

Production

Average FTEs

Average wages

Taxes

3. Optimistic Scenario: High system transformation

vs low constrained counterfactual

+$25b

+$51b

+10,217

+0.28%

+$6b

4. Historic Scenario: Low system transformation vs

historic counterfactual

+$16b

+$32b

+6,667

+0.18%

+$4b

Source: Deloitte Access Economics (2021)

Definitions

GDP: Change in real Gross Domestic Product (GDP) in present value terms over the period 2022 to 2051. GDP includes value added and taxes.

Production: Value of the change in production in present value terms over the period 2022 to 2051. Production is the change in GDP plus the cha

under the Official Information Act 1982nge in intermediate outputs.

Average FTEs: Average change in full-time equivalent employees over the period 2022 to 2051.

Average wages: Percentage change in average annual wages as a result of reform, over the period 2022 to 2051.

Taxes: Value of the change in overall taxes, in present value terms, as a result of reform over the period 2022 to 2051.

Released

© 2021 Deloitte Access Economics

20

4. Scenario Overview

under the Official Information Act 1982

Released

© 2021 Deloitte Access Economics

21

SCENARIO OVERVIEW

Scenario Overview

This section summarises the scenarios considered in our assessment of the potential economic impact

Overview of the counterfactual and system transformation scenarios

Overview of the modelled scenarios

To understand what the economic impact of the reform could be, it is necessary to

We have used two alternative inputs (a low estimate and a high estimate) for both the

determine what the water sector could look like in the absence of reform, and what it could

counterfactual and the system transformation scenario. This formed four modelled scenarios

look like with reform. This can be summarised into two broad scenarios:

for the economic impact assessment:

The counterfactual scenario sets out a pathway for the water sector in the absence of reform.

1. Low Scenario: This scenario is characterised by a low estimate of the expected additional

The counterfactual describes what Councils are expected to spend if the reform did not

spend by Councils in the face of new regulatory constraints, and the spend with reform

proceed, and the extent to which they might face regulatory pressure. Spend under the

based on relationships between historical enhancement and growth investment in the UK

counterfactual case is higher than what Councils have spent historically. Debt and price

and various geographical indicators (WICS Approach 1).

constraints have been applied to the counterfactual. The counterfactual differs from the

2. High Scenario: This scenario is characterised by a high estimate of the expected

status quo, which we have not modelled, given regulatory changes (including the

additional spend by Councils in the face of new regulatory constraints, and the spend

establishment of Taumata Arowai) have been confirmed by Cabinet and are in the process of

with reform based on relationships between historical enhancement and growth

implementation. Data for the counterfactual was based on WICS’ phase two analysis, which

investment in Scotland and various geographical indicators (WICS Approach 2).

was sourced through the Request for Information (RFI) process.

3. Optimistic Scenario: This scenario is characterised by a low estimate of the expected

The system transformation scenario is illustrative of the forward investment profile the reform

additional spend by Councils in the face of new regulatory constraints, and the spend

could enable far more quickly than under the counterfactual. Data for the system

with reform based on relationships between historical enhancement and growth

transformation scenario was based on WICS’ Phase Two analysis, and modelling undertaken

investment in Scotland and various geographical indicators (WICS Approach 2).

by WICS.

4. Historic Scenario: This scenario is characterised by an estimate of the expected spend by

under the Official Information Act 1982

More detail on the policy parameters for each of the scenarios is provided on the

Councils if the regulatory pressure remains but this scenario provides a lower bookend

subsequent pages.

for what might happen in the future if historic rates of expenditure were to continue (i.e.

spend is based on the historical trend), and the spend with the reform based on

Given substantive policy decisions which drive the exact volume and nature of investment

relationships between historical enhancement and growth investment in the UK and

are yet to be made, there is uncertainty around what the economic benefit might be. To

various geographical indicators (WICS Approach 1).

account for this uncertainty, we have modelled four main scenarios, as described opposite.

This report focuses on the Low Scenario (the most conservative scenario) and the High

Released

scenario. We modelled the Optimistic Scenario and the Historic Scenario as sensitivities.

© 2021 Deloitte Access Economics

22

SCENARIO OVERVIEW

Counterfactual Scenario

Under the counterfactual scenario, Local Government retains responsibility for Three Waters services.

Our low and high estimates for the counterfactual draw on constrained expenditure figures provided by DIA. Constrained expenditure reflects the amount of investment that might be

possible without reform, with particular debt and price constraints imposed.* The table below outlines the key, high-level policy parameters underpinning the counterfactual.

Dimension

Description

There is no amalgamation of water services into a small number of WSEs. Instead, the 67 Councils continue to provide Three Waters services,

Number of providers

and retain direct ownership of water assets and responsibility for their funding. Revenue is sourced from households or other Council funds,

and price increases for customers. Some efficiency gains are assumed for larger Councils, but overall efficiency gains are much lower under the

counterfactual than under the system transformation scenario.

The establishment of Taumata Arowai, and the introduction of a new water services regulatory framework, will place greater pressure on

Regulatory standards

Councils to improve service delivery. This is expected to improve compliance, regulatory oversight, and transparency and accountability. More

regional collaboration across Councils in relation to resource management and land use planning is also anticipated.

Volume of investment

A renewed, collective focus on Three Waters services and greater public scrutiny around service delivery, is expected to drive a material

increase in investment. However, a large infrastructure deficit will remain.

Affordability constraints will limit significant investment, and see most Councils deferring much of their required investment. Borrowing is also

Financial constraints

likely to rise, although Councils’ will not exceed 500% debt to revenue limit for water assets. Cou

under the Official Information Act 1982ncilsare expected to offset this higher debt to

revenue ratio for water assets with lower debt to revenue ratios for other assets, so they continue to meet the LGFA debt covenants.

Economic regulation

Economic regulation is not introduced - or at least not to the same extent as under a system transformation scenario – as it is not feasible to

apply this to 67 separate Councils. This also hinders efficiency gains.

Released

*See page 34 for the specific debt and price constraints imposed.

© 2021 Deloitte Access Economics

23

SCENARIO OVERVIEW

System Transformation Scenario

System transformation transfers Three Waters services from Councils to a small number of water services

entities.

Our low and high estimates for the system transformation scenario are sourced from WICS. The system transformation scenario reflects investment that might be possible with reform,

based on either the UK’s or Scotland’s water reform experience. The table below highlights the key, high-level policy parameters underpinning this scenario.

Dimension

System transformation

Three waters services are shifted away from Councils’ remit to a small number of multi-regional water service providers – likely three to five statutory,

Number of providers

asset-owning entities. Other legislative changes to enhance the governance, management and resourcing of Three Waters, are also enacted. These

changes will deliver a range of efficiencies, including elimination of duplicated functions, a greater ability to attract and retain talent, more effective

procurement, and optimisation of asset levels.

As under the counterfactual, the WSEs would be subject to monitoring by Taumata Arowai, and a new water services regulatory framework. This will

Regulatory standards

place greater pressure on Councils to improve netwo k performance. However, Taumata Arowai will be able to perform its role more efficiently, as it will

not need to monitor and regulate 67 separate Councils.

Significant capital investment by the WSEs will be enabled through the separation of balance sheets from local Councils, and financial and operational

autonomy, which will improve access to debt. The package of reforms (aggregation, policy clarity, stronger governance, and economic regulation) will

Volume of investment

also enable new entities to realise economies of scale in the delivery of Three Waters services, which can help to offset the significant forward

investment requirements. As a result, capex is significantly higher under the system transformation scenario relative to the counterfactual, and the

infrastructure deficit is reduced faster Government funding will support the transition and establishment phases of reform.

under the Official Information Act 1982

Financial constraints

The WSEs will be better able to borrow to fund infrastructure requirements than Councils, as strengthened financial structures will allow them to take on

more debt.

Economic regulation

Amongst other things an economic regulatory regime regulates the maximum revenue WSEs can earn for a given level of investment, taking into

account required levels of service.

Released

© 2021 Deloitte Access Economics

24

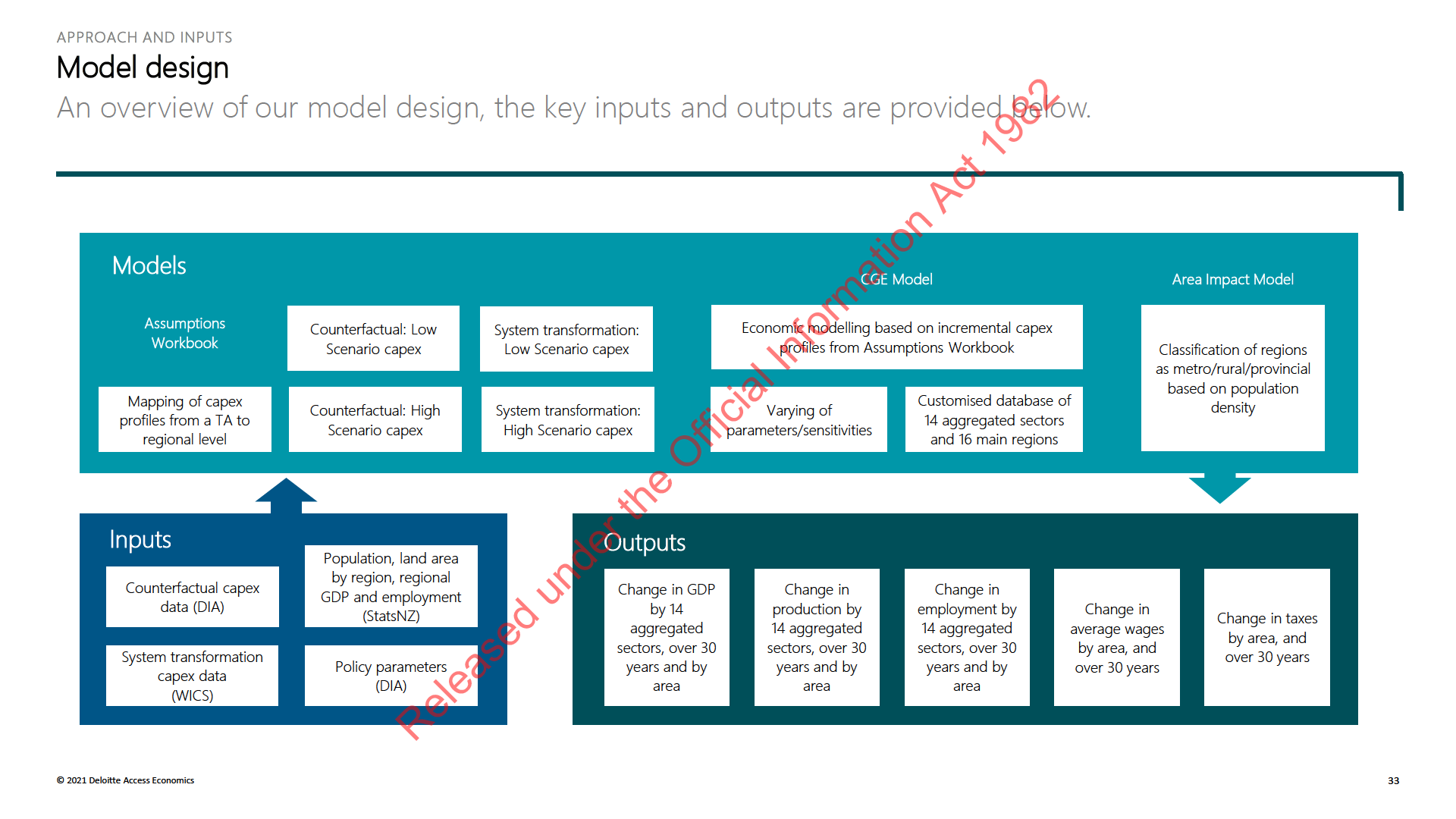

5. Approach and Inputs

under the Official Information Act 1982

Released

© 2021 Deloitte Access Economics

25

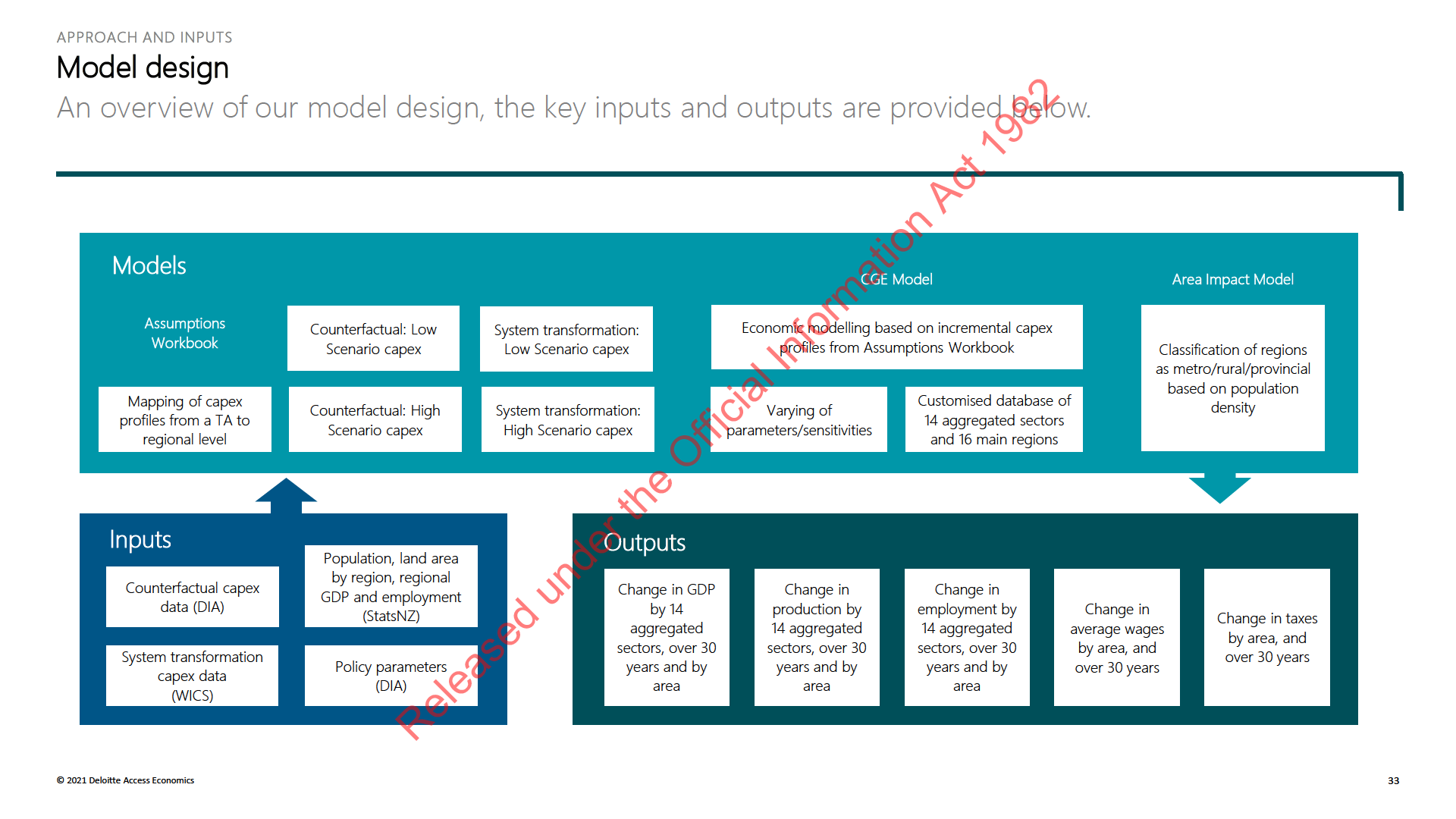

APPROACH AND INPUTS

Formulating the shock for the Economic Impact Assessment

We have aggregated incremental capital expenditure profiles from individual Councils/Territorial

Authorities into 16 regions to include within our Model.

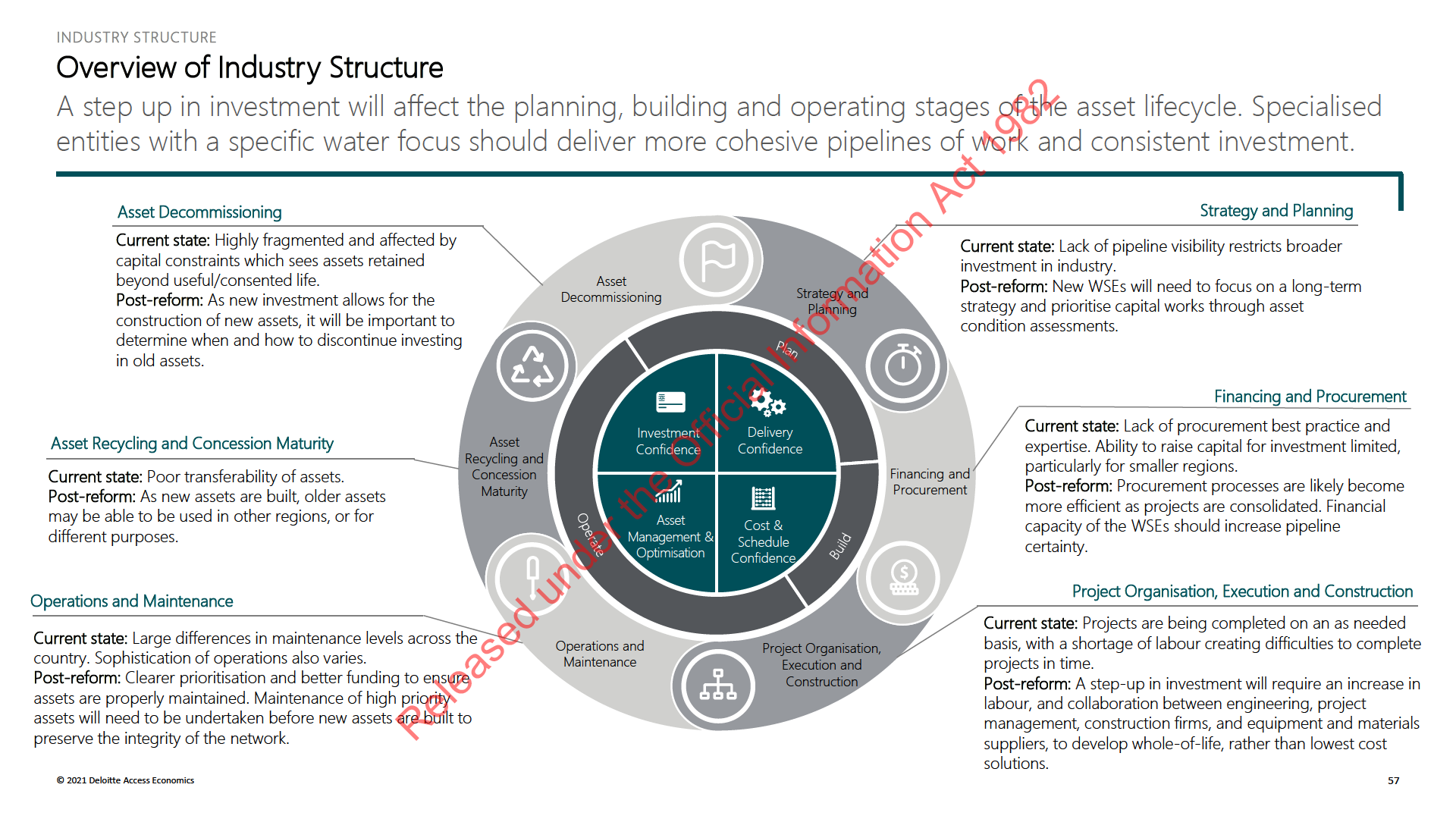

The Three Waters infrastructure network consists of infrastructure and processes used to collect, store, transmit through reticulation, treat, and discharge, Three Waters. At its core, reform is

intended to address the root causes of systemic failure in the existing system for delivering Three Waters. A key benefit of reform is that it addresses the challenges local authorities face in

planning for and investing in long term infrastructure needs, by establishing new WSEs with the operational and financial autonomy to undertake a significant uplift in investment to address

historic underinvestment, and meet health and environmental standards. DIA and WICS provided capital expenditure (capex) data for the system transformation and counterfactual scenarios,

which projected the likely spend with and without reform.

As discussed earlier, CGE modelling considers the flow-on effects of investment in the water sector on other sectors, while accounting for the overall constraints in the economy (e.g. availability

of labour). We formulated the CGE shock according to the steps below:

3. We applied the incremental regional

investment (i.e. capex data) as a shock to

the CGE model. This shock was applied to

the water sector on a regional basis.

2. We aggregated TA level incremental

investment (i.e. capex data) to a regional

level.

1. We used investment (i.e. capex data), at

an individual Council/ Territorial Area (TA)

level, over 30 years to calculate the

under the Official Information Act 1982

incremental spend based on the difference

between the system transformation and

counterfactual data.

Released

Source: Deloitte Access Economics (2021)

© 2021 Deloitte Access Economics

27

APPROACH AND INPUTS

Formulating the shock for the Economic Impact Assessment

We modelled an increase in capex, targeted towards the water sector. The resulting increase in water

sector output was assumed to be driven by improved capital productivity.

1. The core input into the CGE model for each scenario was incremental capital expenditure

iii. Deloitte Access Economics used the capex data for the water sector and

i.e. the difference between projected capex under the system transformation scenario,

implemented this as capital-productivity induced expansion in the water sector’s

and projected capex under the counterfactual.

output. We have interpreted the figures in terms of their intended outcome (e.g.

2. The incremental investment data was collected at an individual Council/TA level, and

improved service outcomes), rather than the investment’s expenditure effect. To

aggregated to a regional level based on the regional boundaries defined by Statistics

determine the appropriate link between the level of capital expenditure and the

New Zealand and the location of each TA within a region. Where a TA’s geographic

implied improvement in the water sector’s output, we pro-rated the investment

boundary spanned two or more regions, we allocated that TA to the region with the

figures down by the ratio of capital as an input to the water sector as well as the

greatest overlap.

share of capital usage, for which the water sector accounts. So in cases where a

3. The regional incremental investment profiles were used as the shock to our CGE model

region is set to receive a given increase in investment, it instead receives a proxied

and implemented as capital-productivity induced expansion in the water sector’s output:

boost to water output which is achieved via more efficient capital coming online.

Therefore, by focusing on a capital productivity shock, the model cannot factor in

i.

The reform aims to establish new multi-regional WSEs with financial and

underlying economic inefficiencies associated with the counterfactual.

operational independence. The new entities would have enough balance sheet

capacity to raise debt to finance water investment requirements, while being

In addition, our counterfactual already includes a significant step up in investment

subject to economic regulation that regulates the maximum revenue these entities

relative to the status quo. The economic modelling cannot explicitly account for the

can earn. The water investment will be funded through a mix of user charges and

impact of existing systemic challenges in the water sector, such as reactive and

improved efficiencies. This means the policy to be modelled has three key

inefficient spend, and a lack of clear career pathways – which will likely continue under

components: an increase in investment (making up for historical underspend),

the counterfactual. As a result, the results presented in this report are a conservative

efficiency improvements in the water sector, and changes in user charges.

estimate of the potential economic impact of reform.

ii.

At present, there is only concrete information on the capex component. Simulating

under the Official Information Act 1982

a blanket increase in investment across the various regions would give biased

Water infrastructure is complex, expensive, and largely located underground. Based on

impacts – especially given the sector-specific nature of the investment and the

WICS data, below ground infrastructure is expected to comprise approximately 60% of

general nature of capital in our CGE Model. Without some way to specifically

investment. A number of studies suggest underground infrastructure leads to higher

target the water sector, the results would struggle to tell a meaningful story, given

local employment multipliers, given the relatively labour intensive nature of associated

generic capex shocks tend to have broad-based benefits with particular

capex. Due to data limitations in the counterfactual, the economic impact assessment

concentration in construction, trade and business services.

focuses on the impact of the total investment profile. The Affected Industries section

qualitatively discusses the different impacts above versus below ground investment

Released

could have.

© 2021 Deloitte Access Economics

28

APPROACH AND INPUTS

Formulating the shock for the Economic Impact Assessment

We included a transition path to assess the economic impact of the reform

To assess the economic impact of reform, Deloitte Access Economics applied a transition

period to the reform programme, thereby delaying some of the economic impact of reform.

For the purposes of this report, we assumed a transition path of six years.

Based on international experience, the transition path could be shorter if existing processes

are already in place with the establishment of the new water entity. For example, Victoria

(Australia) had a shorter transition period, where Ballarat Water Board absorbed a number of

smaller water entities. However, if wholly new processes or entities need to be established,

the transition period may be longer, as was the case with the Tasmanian water reform.

This reform is shaping up to be one of the largest in New Zealand’s history, given it involves

moving from 67 local Councils to a small number of new water entities. Establishing the new

entities will be a large and complex process. The first phase of reform will need to focus on

the establishment of the new entities, before reform activities themselves can get fully

underway. This implies the transition period could be relatively long, with time needed to

complete entity establishment, commence scoping of capital work requirements, and

spending money. Accordingly, efficiency savings are likely to be delivered gradually over

time as the new entities are established, and systems and processes take effect.

The transition path will also be influenced by the political will to drive reform, including the

level of desire to accelerate the pace of change. For example, commitments that no staff will

under the Official Information Act 1982

lose their jobs will affect the pace of change.

Released

© 2021 Deloitte Access Economics

29

APPROACH AND INPUTS

Scenarios modelled

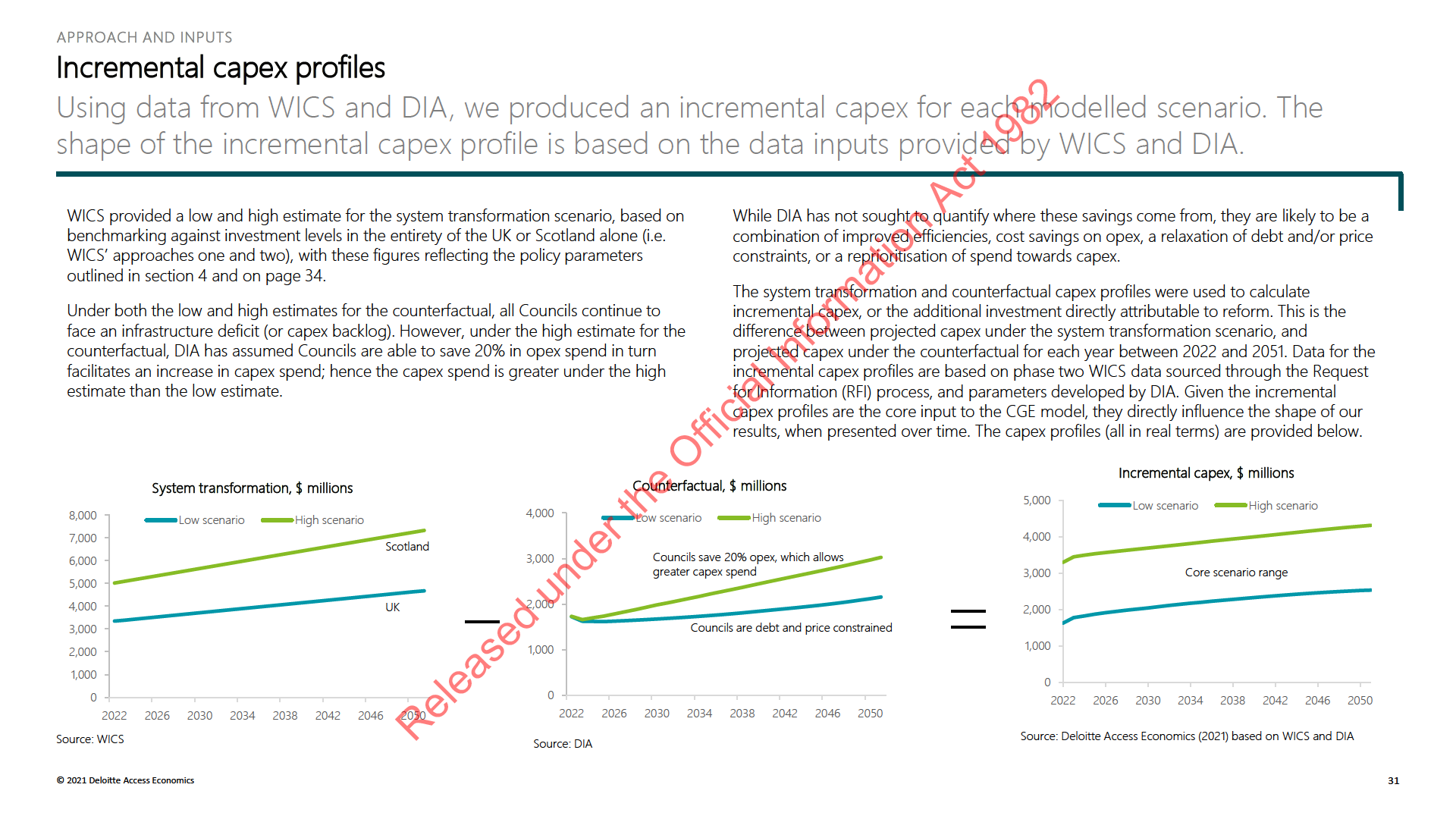

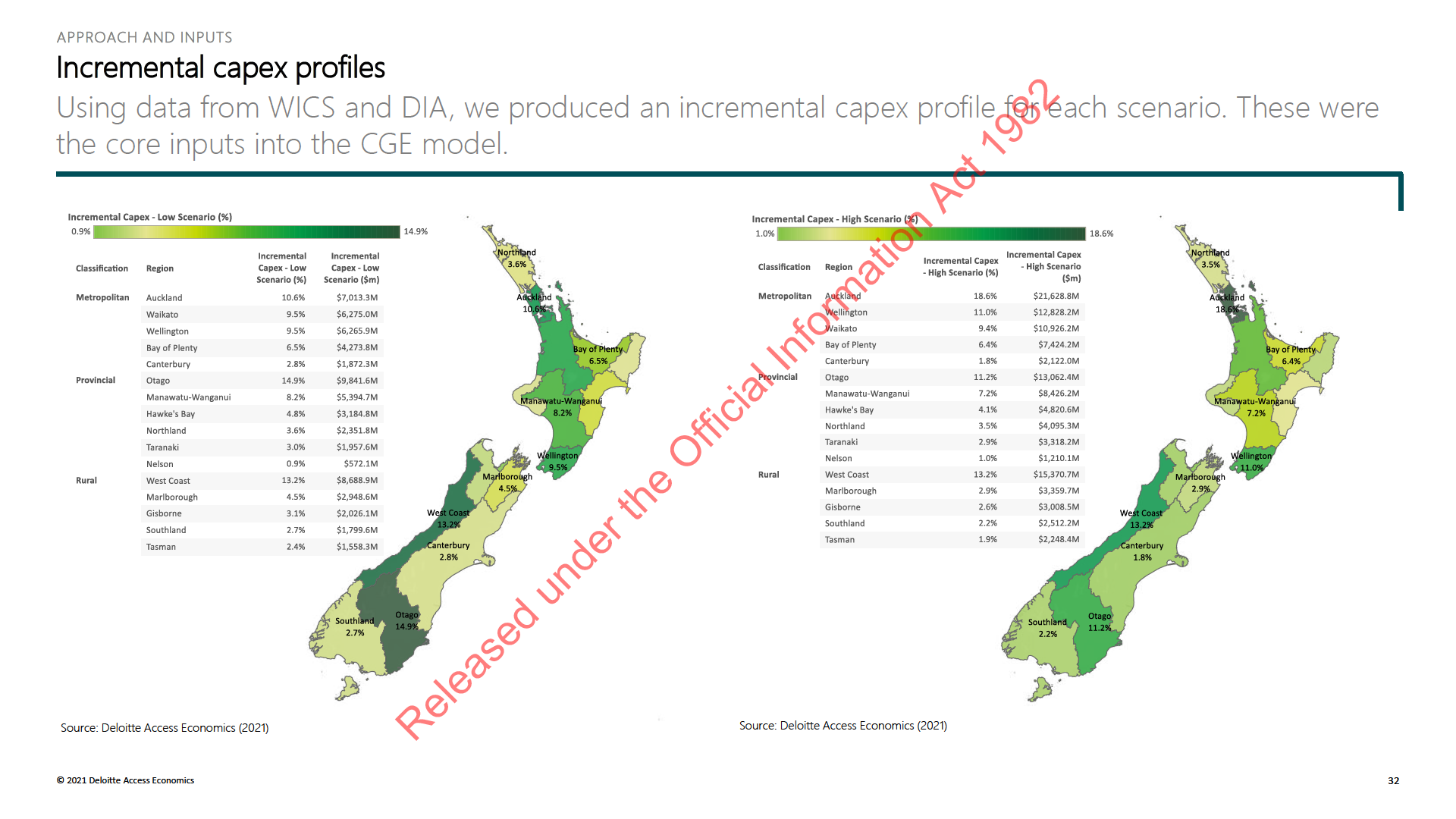

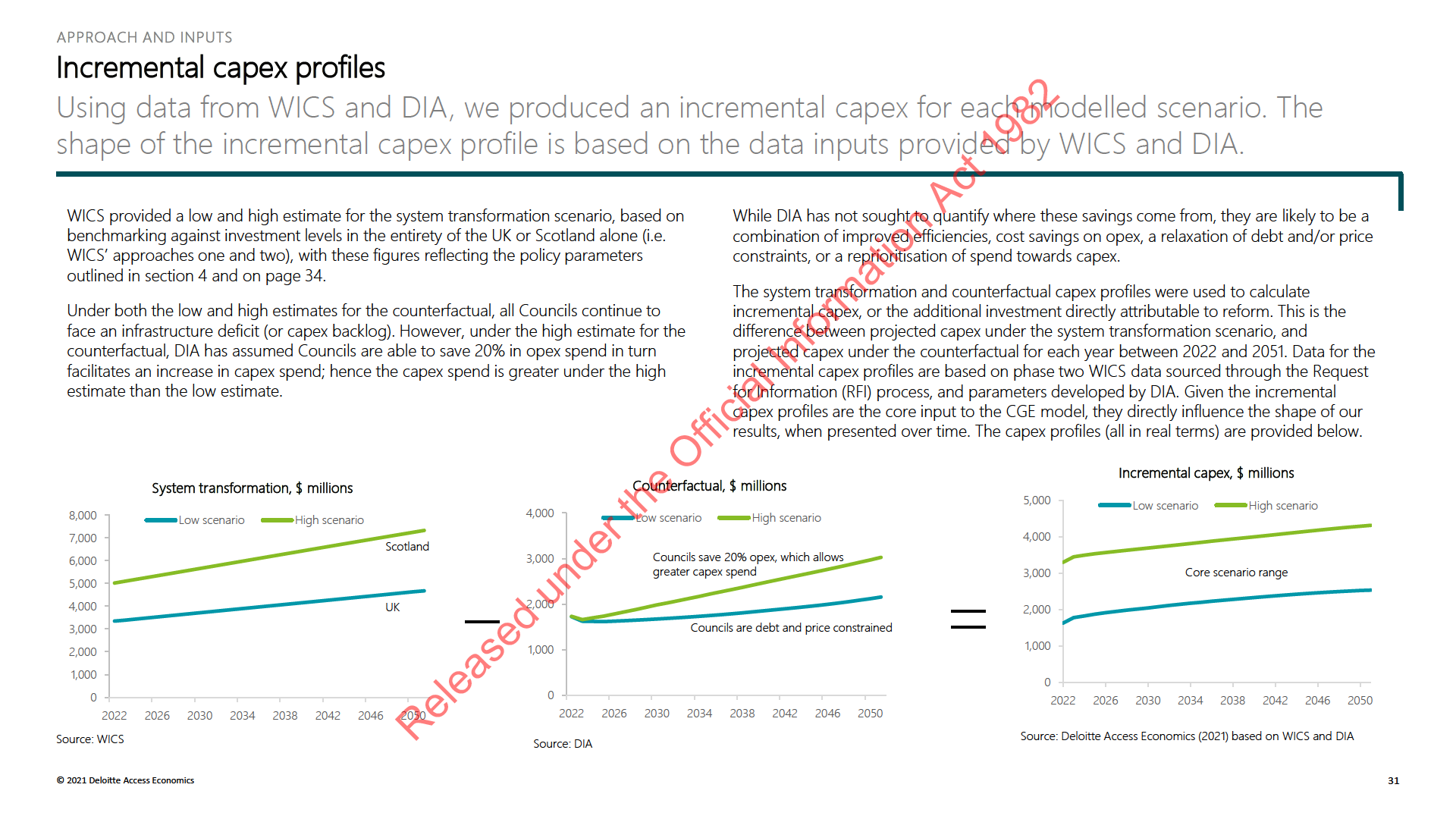

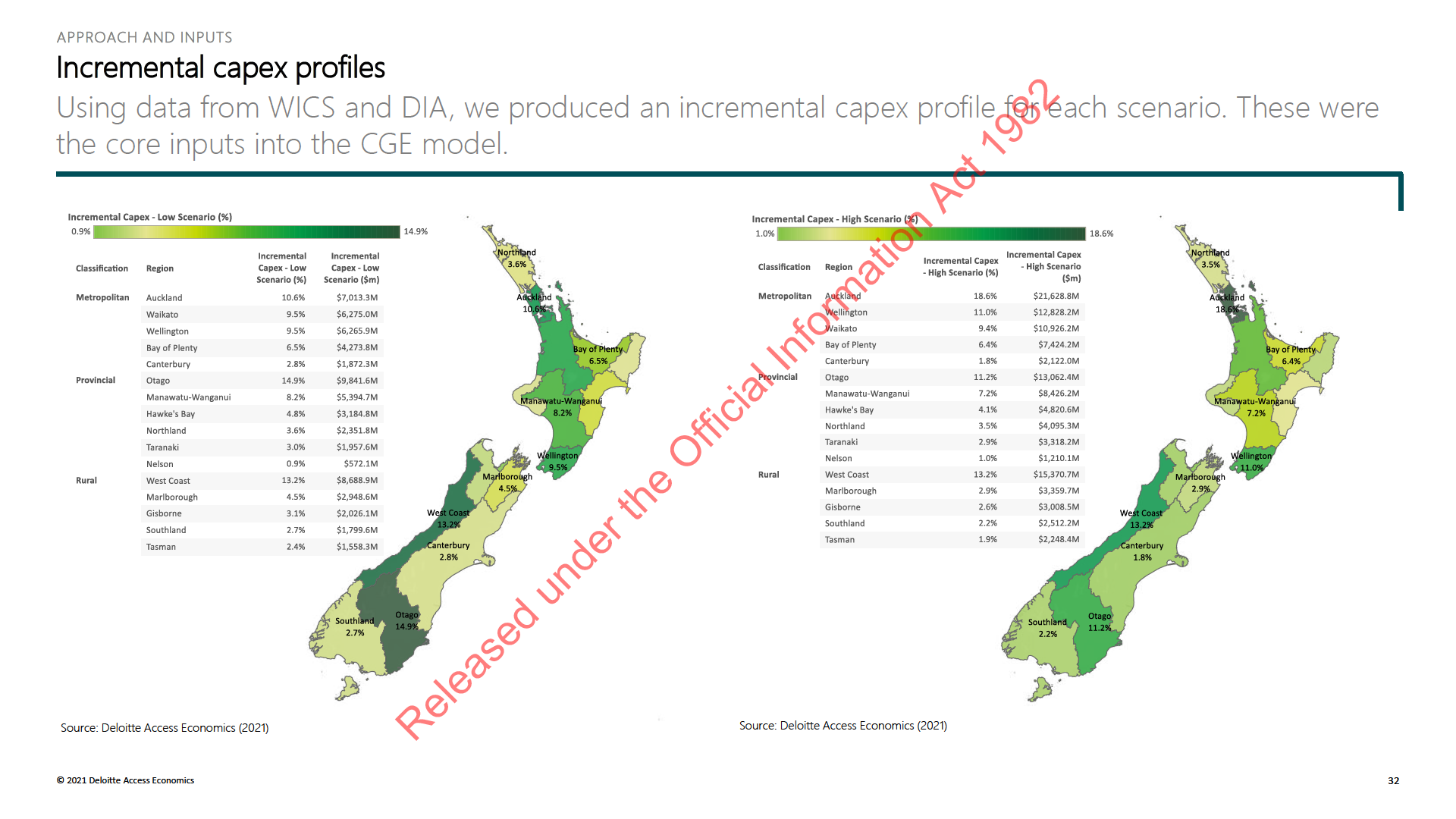

We modelled four scenarios, with incremental capital expenditure the key input for each scenario.

To understand the potential economic impact of reform, we modelled four scenarios our in-house CGE model.

The table below summarises the total investment* required under the counterfactual and system transformation scenarios, under different data inputs – either a low estimate or a high

estimate, or in the case of the “Historic Scenario”, the counterfactual is based on trends in historic spend.

Water investment projected under each modelled scenario and the incremental investment applied to assess the economic impact of reform (Total capex, 2022 to 2051, billions)

Scenario

System transformation capex

Counterfactual capex

Incremental capex

1. Low Scenario: Low system transformation vs low constrained

counterfactual

$120b

$55b

$65b

2. High Scenario: High system transformation vs high

counterfactual constrained

$185b

$69b

$116b

3. Optimistic Scenario: High system transformation vs low

constrained counterfactual

$185b

$55b

$130b

4. Historic Scenario: Low system transformation vs historic

counterfactual

$120b

$44b

$76b

under the Official Information Act 1982

Source: Deloitte Access Economics (2021)

*We have not modelled operating expenditure (opex) Modelling opex would likely show an additional economic benefit, which implies the results presented in this report are conservative.

Released

© 2021 Deloitte Access Economics

30

APPROACH AND INPUTS

Key data sources

WICS’ system transformation profile uses two approaches: the investment in the UK (approach one) or

Scotland alone (approach two). DIA’s counterfactual capex profile assumes debt and pricing constraints.

System transformation data

Counterfactual

WICS provided data based on their defined Approaches One and Two for the system

DIA drew on WICS data to forecast capex under the counterfactual scenario. A starting

transformation scenario.

position was determined for Councils (i.e. revenue, operating expenditure, debt) based on

WICS’ phase two analysis, and in turn the level of capital expenditure that might be

Approach one

possible if Councils reach their debt limits, and raise water prices in line with historic

Under approach one, the ‘Revised approach used in phase one’, WICS estimated

increases.

potential expenditure on enhancement, growth and renewals. Enhancement and growth

expenditure refers to the provision of new assets or enhancement of existing assets, while

The assumed water price increase is a maximum of 4.4% per annum, in line with the

replacements refer to capital maintenance expenditure needed to maintain existing

historical rate of increase (between 1993 and 2018).

service levels to customers.

As mentioned, the debt limit imposed does not allow Councils to exceed a debt to

Enhancement expenditure was modelled based on investment in the UK, with population

revenue ratio of 500% for water assets. Where the starting debt to revenue ratio is below

and geographic drivers accounted for. A similar method was used to estimate growth

500%, it is assumed the debt to revenue ratio increases over time.

investment, but data for this was sourced from the RFI. This included growth from

A 500% debt to revenue ratio for water assets is a conservative assumption, as most

projected new connections reported by Councils, and a cap per connected citizen of

Councils use lower debt to revenue ratios in other areas to offset a higher debt to

$70,000 to account for financial constraints faced by Councils. WICS uses growth

revenue ratio for water assets, ensuring they do not breach a debt to revenue ratio of

projections provided by Councils. Renewals were modelled in terms of the average

250%.

annual replacement expenditure (i.e. economic depreciation), based on asset values

reported by Councils.

The forecast interest rate is assumed to be 3.5%.

under the Official Information Act 1982

Approach two

This aligns with approach one, with modelling undertaken based on population and

geographic drivers, growth adjustments, and capping. However, modelling was

benchmarked against Scotland only (rather than all of the UK). This was deemed

appropriate as Scotland has many geographical and economic similarities with New

Zealand.

Released

© 2021 Deloitte Access Economics

34

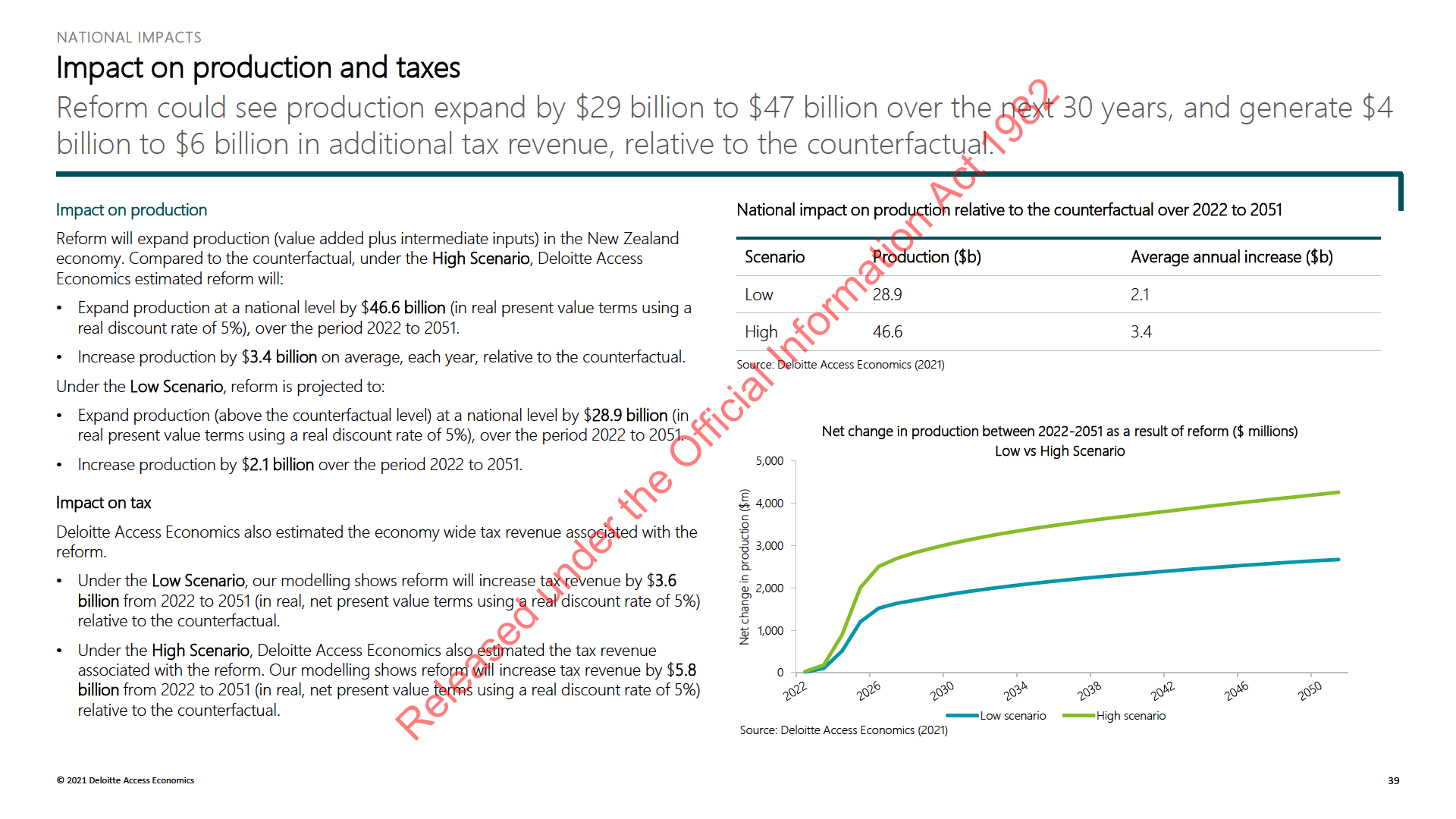

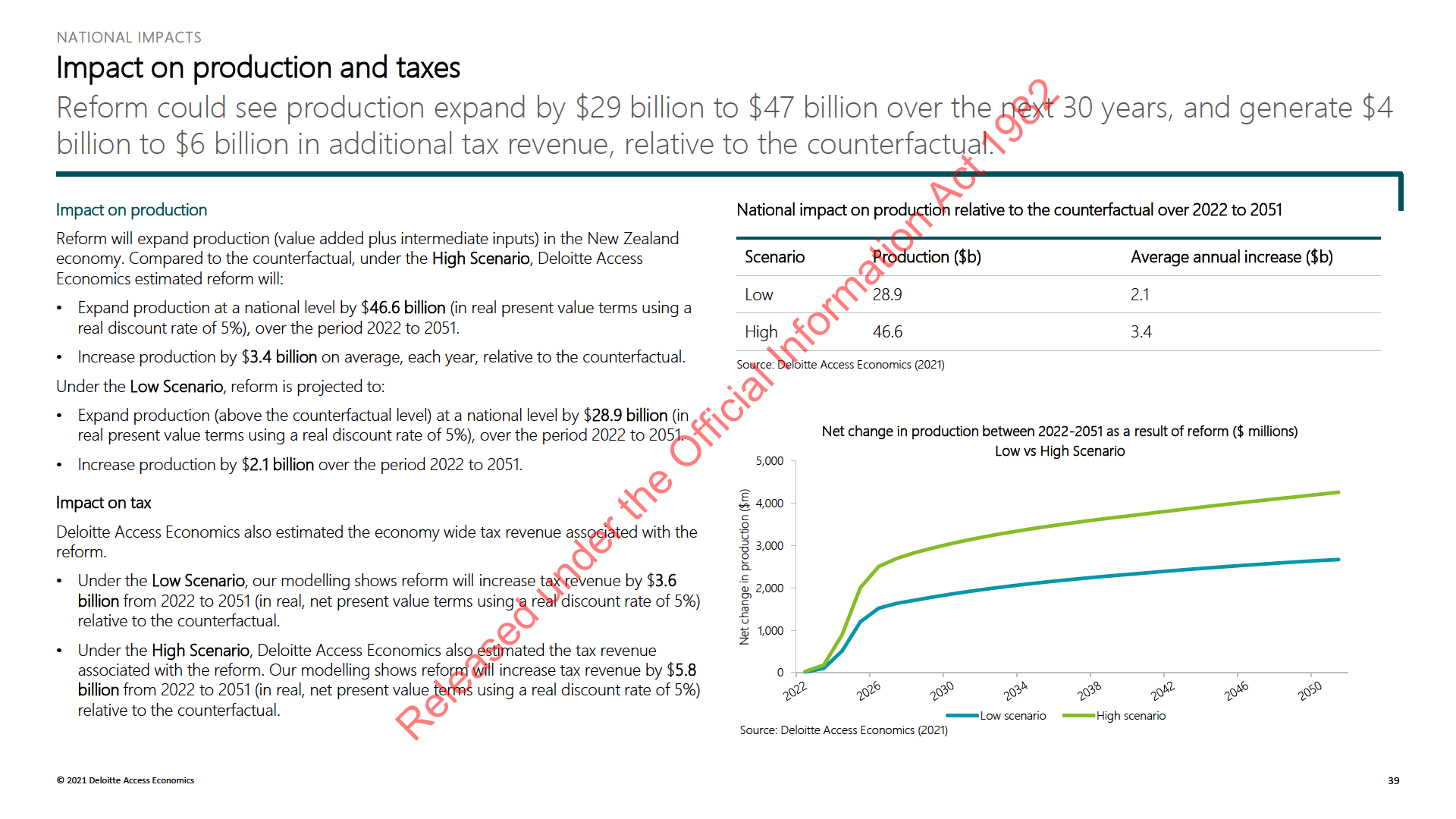

6. National Impacts

Impact on gross domestic expenditure, production and tax

implications

under the Official Information Act 1982

Released

© 2021 Deloitte Access Economics

35

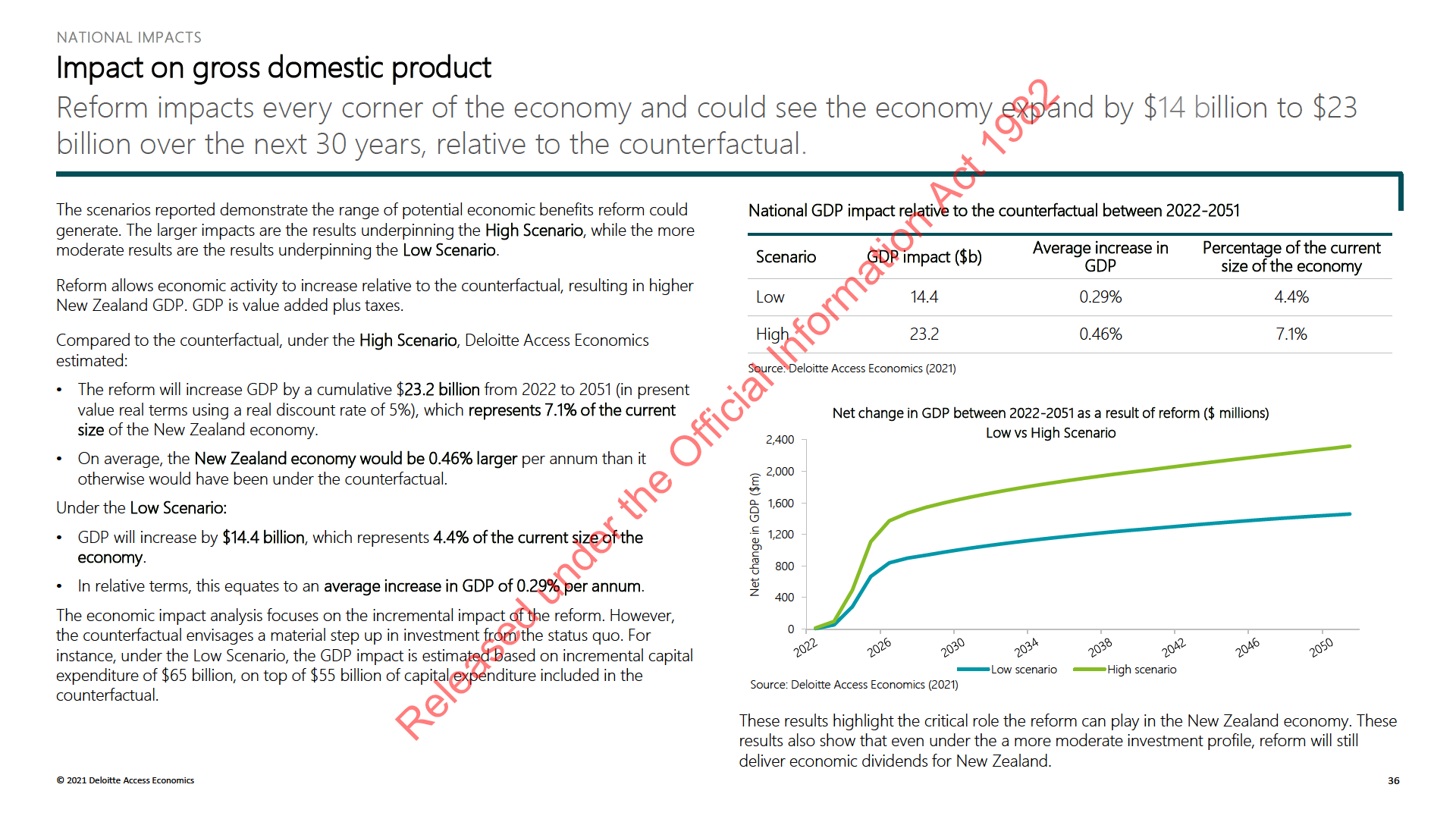

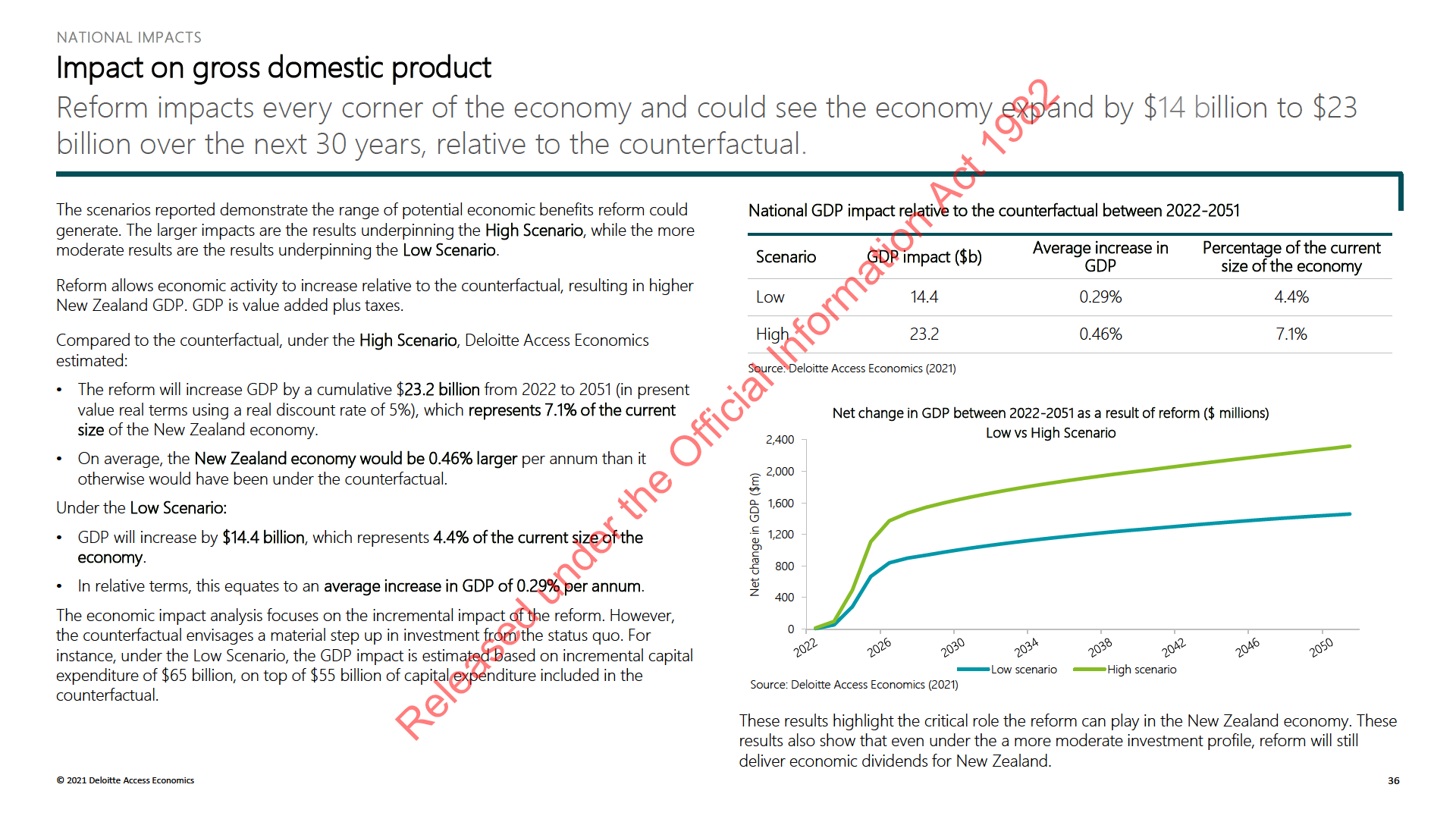

NATIONAL IMPACTS

What impact does reform have across industries?

Reform supports economic growth across all sectors.

The impact on sectors is not equally distributed. The impact of the reform across sectors

The modelling of sector GDP in this report defines the water delivery sector as water

are illustrated in more detail on the next slide. There is an increase in activity across all

supply, sewerage, and drainage services as well as waste collection, treatment and

sectors, particularly those that are more capital and water intensive. This activity is initially

disposal services based on ANZIC codes. This definition will not pick up economic activity

driven by activity in the water delivery sector associated with reform, and subsequently

in the broader water sector supply chain (e.g. water engineers and construction of water

there are positive flow-on impacts to sectors across New Zealand.

assets).

Under the Low Scenario, Trade ($1.5b) Financial services ($0.7b), Construction ($0.8b),

We recognise the economic activity in the water sector and affected sectors are fluid and

Business Services ($2.5b) and Other Services ($5.1b) are expected to see the largest

it may be difficult to attribute activities to a specific ANZIC code. For example, an engineer

increases in GDP as a result of reform. Growth in GDP in the Business Services sector due

involved in strategy and planning of a water project will be captured under Business

to reform may be associated with greater activity at the Strategy and Planning, and

Services, even though it relates to the water sector. Similarly, construction activity as a

Financing and Procurement, stages of the water industry life cycle. The sector impact

result of the reform will be captured under Construction, even though part of the project

under the High Scenario is also summarised in the table below.

organisation and execution may be conducted by a Professional firm.

The GDP impact on the water delivery sector may start to decline in relative terms versus

The Other Services sector is forecast to see the largest increase in GDP. Other services

the counterfactual from 2038 onwards, as cost savings and efficiencies increase. In today s

includes Public Administration & Defence, Education, Human Health and Social Work

terms, GDP in the water delivery sector still increases by $0.3b between 2022 and 2051.

Activities, and Dwellings (i.e. residential housing). These are large sectors, which all benefit

The step-up in investment increases output in the water delivery sector, via improved

from the GDP and output growth facilitated by reform.

capital efficiency. Any relative decline in water sector GDP is offset by an increase in

intermediate inputs (i.e. how reform benefits all other sectors).

under the Official Information Act 1982

GDP impact relative to the counterfactual between 2022 to 2051, by selected sectors ($b)

Sector

Trade

Financial Services

Construction

Business Services

Other Services

Low Scenario

1.5

0.7

0.8

2.5

5.1

High Scenario

2.4

1.2

1.4

4.1

8.2

Released

Source: Deloitte Access Economics (2021). Note the figures in this table do not add up to the total GDP impact, as this table only presents the sectors with the largest GDP impact as a result of reform.

© 2021 Deloitte Access Economics

37

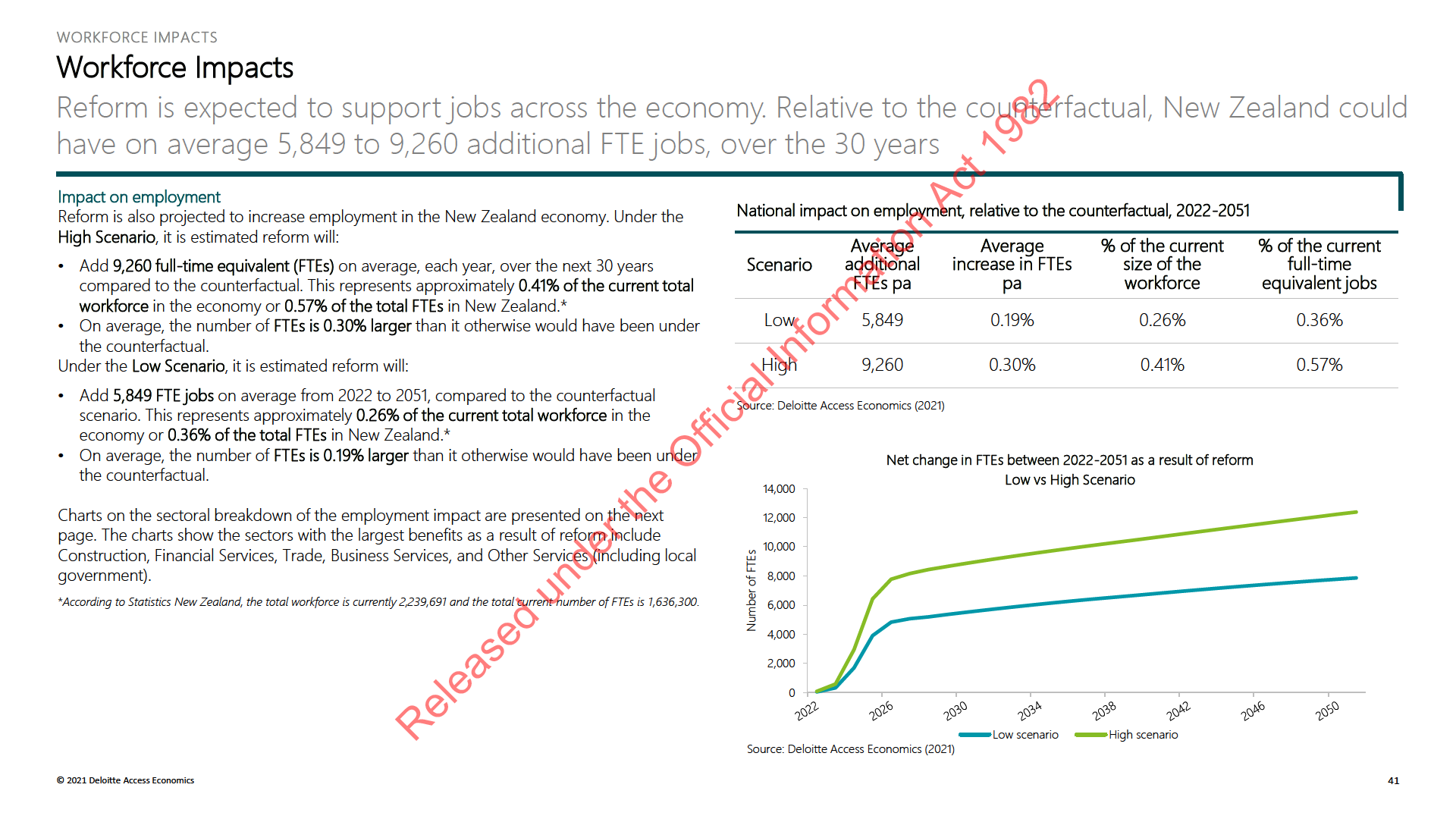

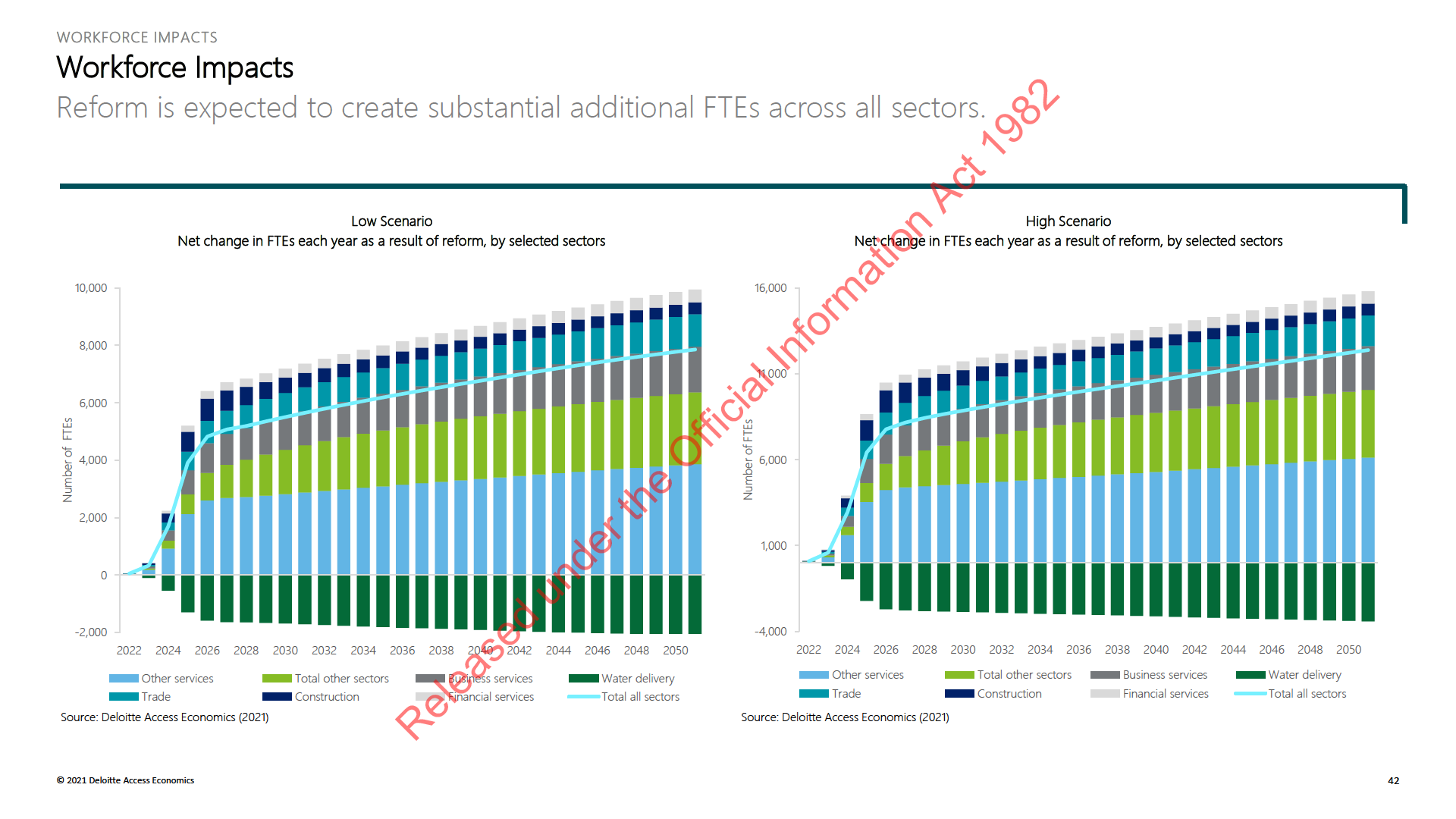

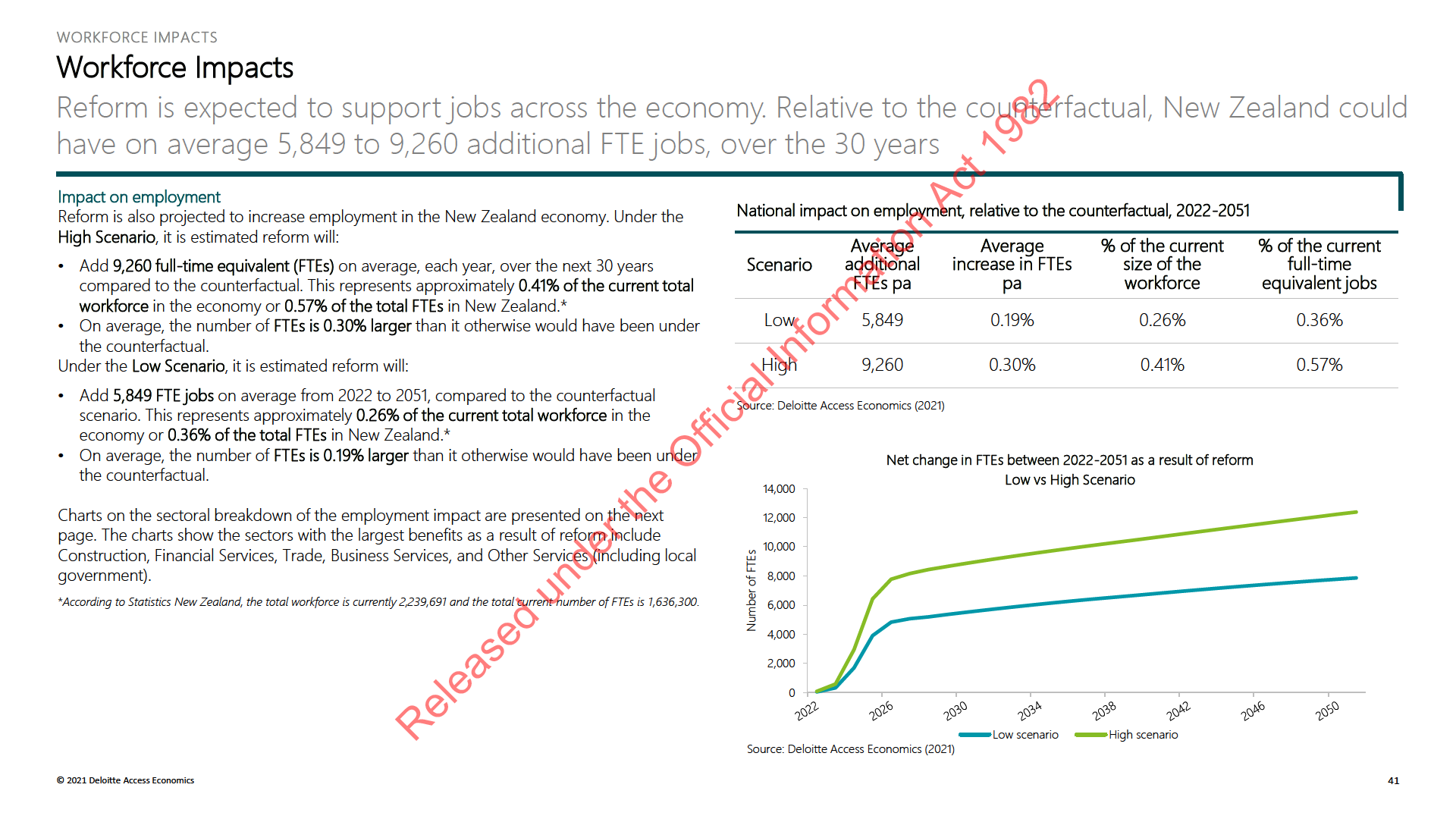

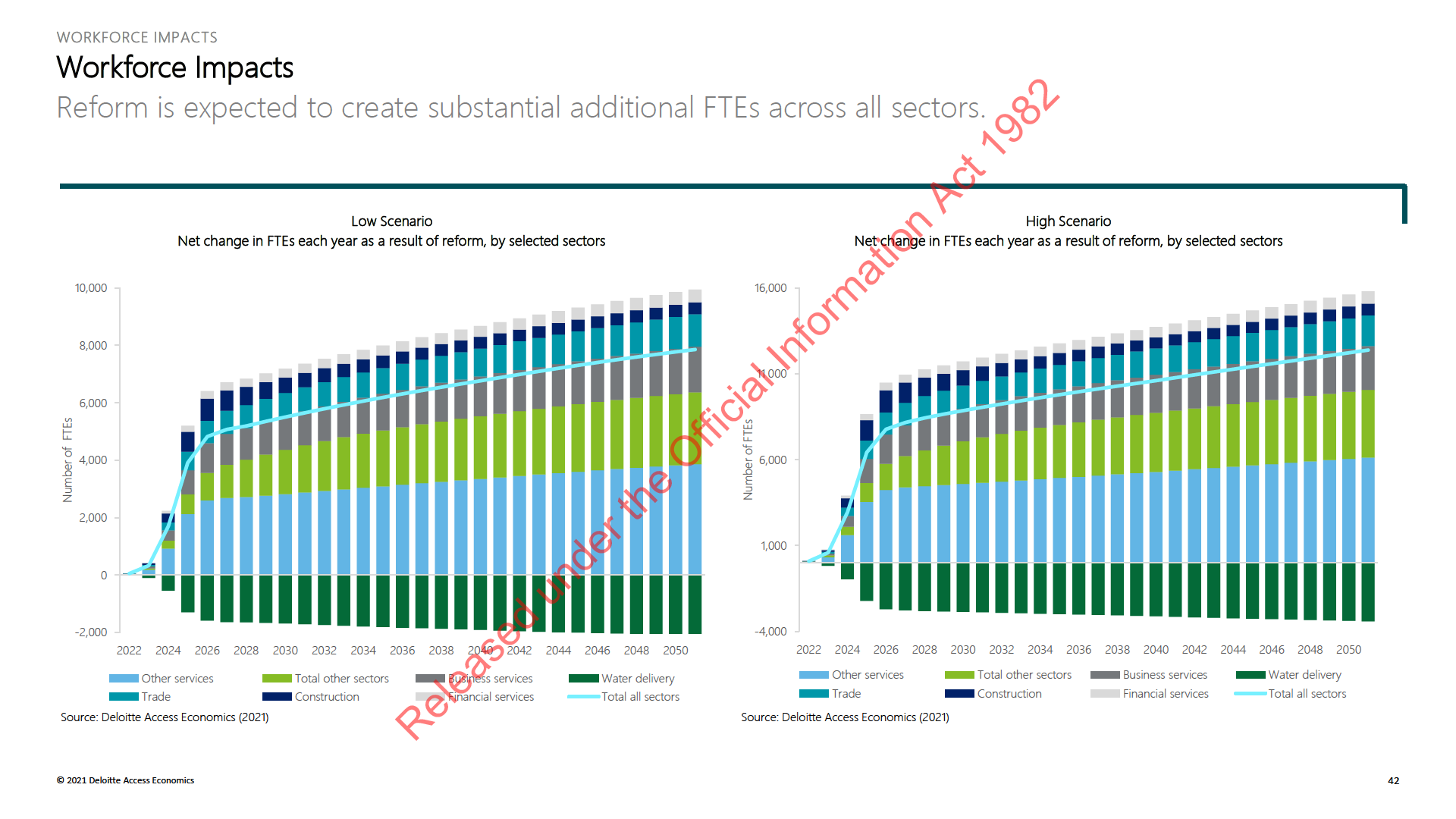

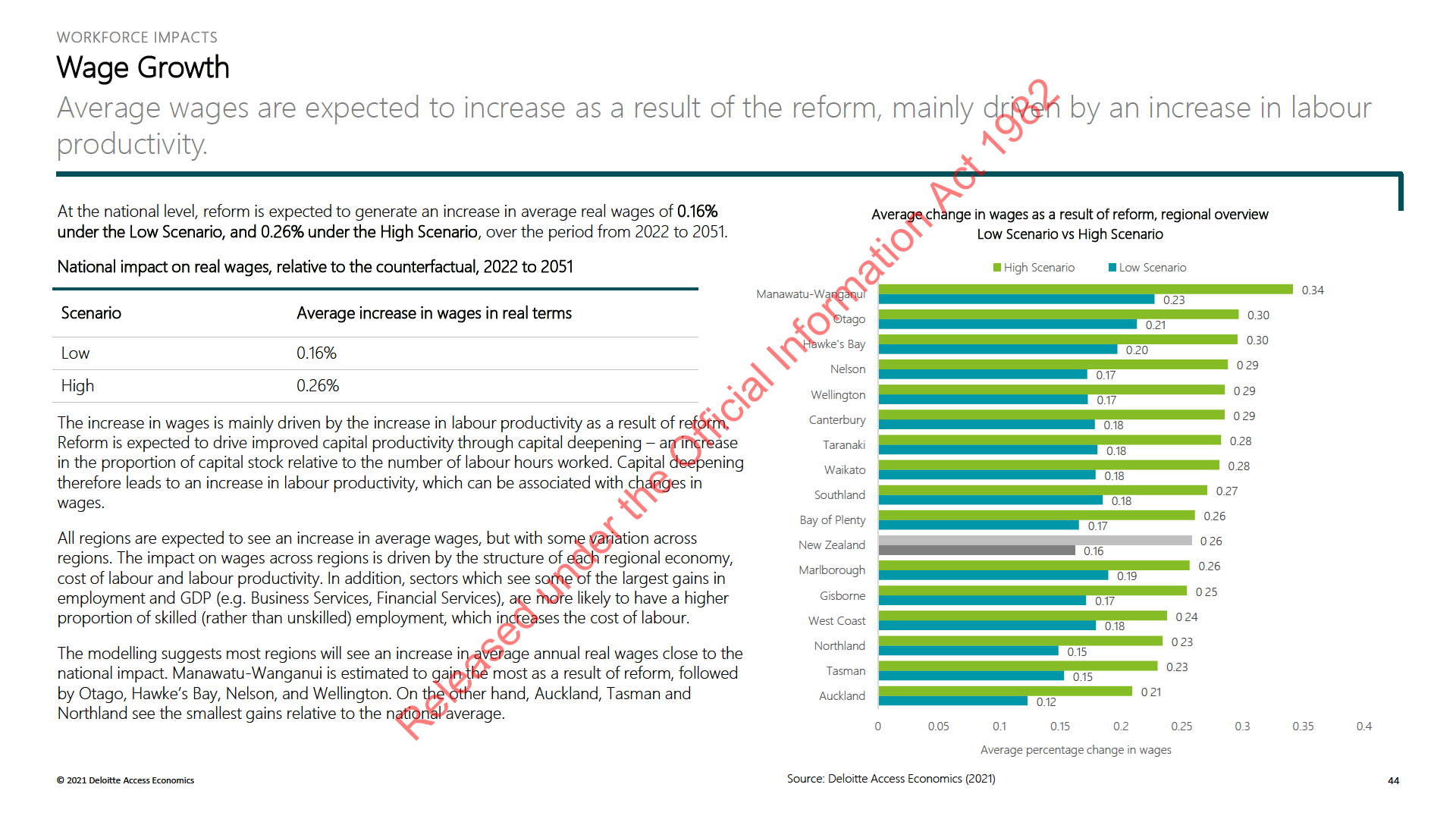

7. Workforce Impacts

under the Official Information Act 1982

Released

© 2021 Deloitte Access Economics

40

8. Distributional Impacts

How is the impact distributed across regions and across

metropolitan, provincial and rural areas?

under the Official Information Act 1982

Released

© 2021 Deloitte Access Economics

45

DISTRIBUTIONAL IMPACTS

Distributional Impacts

Every region in New Zealand is positively affected by the economic impacts of the reform, but not all

regions are impacted equally.

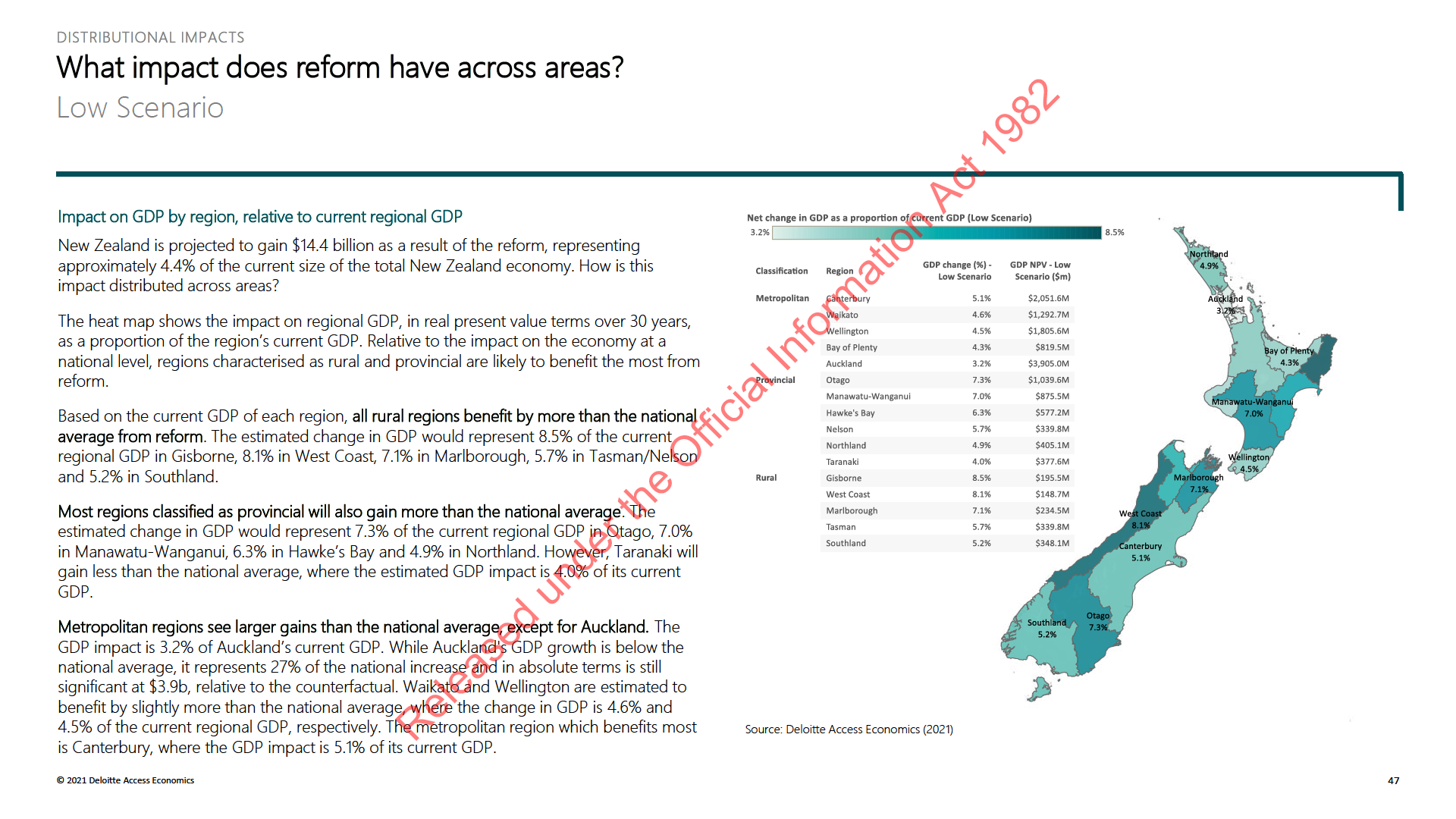

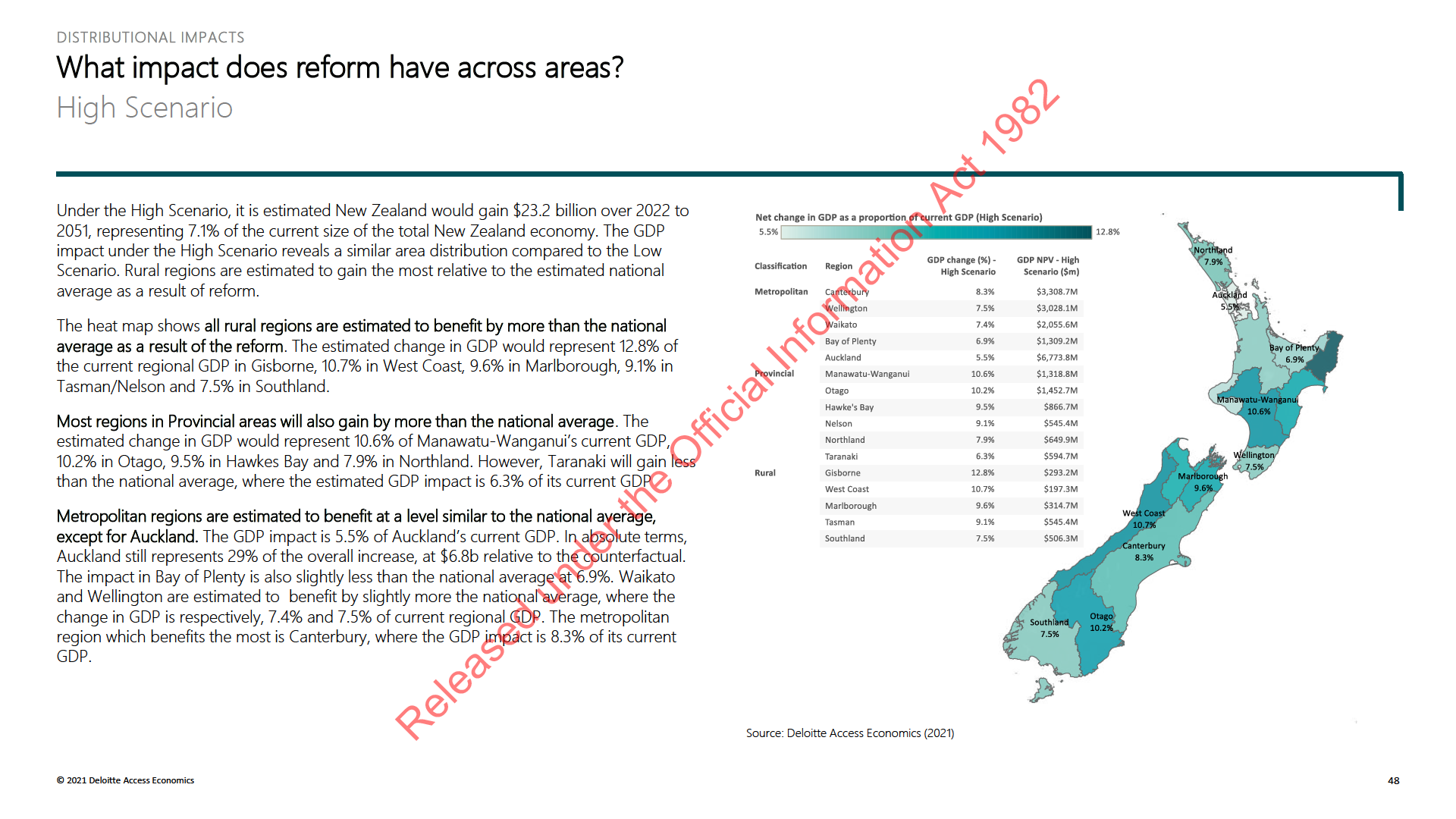

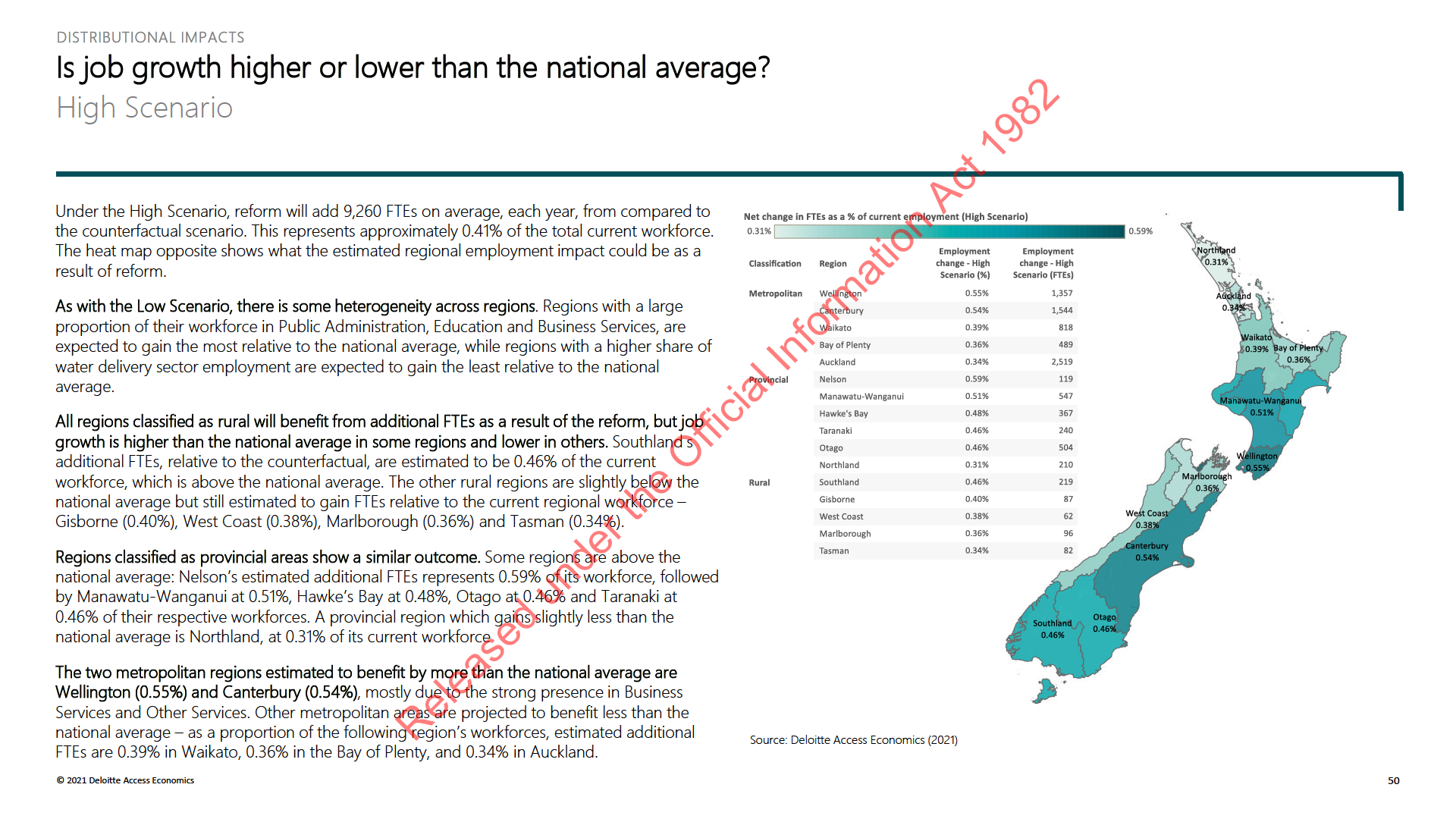

The previous section of the report explored the national economic impact of the reform –

Regions classified as metropolitan

Regions classified as rural

but that’s only part of the story. Every region is positively affected by the economic impact of

reform, with increases in GDP, production, employment, taxes and average wages are

Auckland

Gisborne

expected. However, not all regions are impacted equally – the magnitude of the increase in

Wellington

Tasman

GDP and employment differs considerably across regions, and when considered in terms of

metropolitan, rural and provincial areas. Rural and provincial areas (per the classifications

Bay of Plenty

Marlborough

opposite, based on population density) have the most to gain from reform, as these areas

Waikato

West Coast

currently face large infrastructure deficits.

Canterbury

Southland

Heterogeneous impacts across regions are the result of differing structures and dynamics of

each region’s economy. Import-oriented regions (that is, inter-regional importing, as well as

Regions classified as provincial

imports from overseas), benefit more than areas which are more exposed to domestic

Northland

demand (spending and production within that area). As a result, smaller, import-oriented

regions such as the West Coast, Gisborne, Marlborough and Southland see larger relative

Hawke's Bay

benefits.

Taranaki

We classified the 16 main regions into metropolitan, provincial and rural areas, based on

Manawatu-Wanganui

population density and regional characteristics to consider local impacts of reform. Opposite

Nelson

is a summary of the classification we used:

Otago

Source: Deloitte Access Economics (2021)

under the Official Information Act 1982

Released

© 2021 Deloitte Access Economics

46

10. Overview of Affected Industries

under the Official Information Act 1982

Released

© 2021 Deloitte Access Economics

51

OVERVIEW OF AFFECTED INDUSTRIES

Introduction & Reform Objectives

Targeted stakeholder interviews were undertaken to understand the implications of reform on a number

of industries.

We engaged with a cross section of service providers through an interview process. The

• Moving the supply of Three Waters services to a more financially sustainable footing, and

purpose of these interviews was to understand providers’ current role in the sector and

addressing the affordability and capability challenges faced by small suppliers and

how the industry in which they operate (the “Affected Industry”) might evolve under

Councils;

reform. While the information and insight gained through the interview process has been

anonymised, all statements and sentiments reflected in this report can be referenced back to

• Improving transparency about, and accountability for, the delivery and costs of Three

documented interview notes.

Waters services, including the ability to benchmark the performance of service providers;

and

In undertaking the interview process, we have been mindful of the structural proposals and

• Undertaking the reform in a manner that enables local government to further enhance

aim of Government with respect to the reform. This provides critical context for the industry

the way in which it can deliver on its broader “wellbeing mandates” as set out in the Local

engagement process. In particular, the Three Waters reforms are expected to culminate in

Government Act 2002.

the establishment of a small number of WSEs in 2023 and to drive a material step up in

investment in the sector.

By creating a small number of WSEs, the reforms intend to ensure:

The aims of reform expected to have implications for Affected Industries include:

• Entities are of significant scale to deliver benefits from aggregation over the medium to

long-run;

• Significantly improving the safety and quality of drinking water services, and the

environmental performance of drinking water and wastewater systems (which are crucial

• Entities have independent balance sheets to enhance access to capital and alternative

to good public health and wellbeing, and achieving good environmental outcomes);

funding instruments, driven by increased balance sheet strength; and

• Ensuring all New Zealanders have equitable access to affordable Three Waters services;

• Entities are specialist providers with a core focus on delivering drinking and wastewater

services as a priority.

• Improving the coordination of resources, planning, and unlocking strategic opportunities

under the Official Information Act 1982

to consider New Zealand’s infrastructure and environmental needs at a larger scale;

We note that Affected Industries include suppliers to water providers. While they form a

critical part of the supply chain, they are broader than the water sector as defined for the

• Increasing the resilience of Three Waters service provision to both short and long-term

risks and events, particularly climate change and natural hazards;

purposes of our CGE modelling.

Released

© 2021 Deloitte Access Economics

52

OVERVIEW OF AFFECTED INDUSTRIES

Affected Industries Stakeholder Engagement Process

Targeted stakeholder interviews were undertaken to understand the implications of the reform on a

number of different industries.

There was generally a very good level of awareness of the proposed reform and

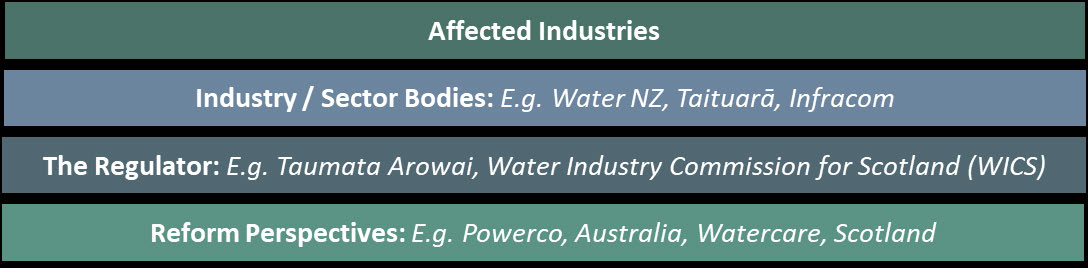

A schematic of the interview coverage is set out below:

stakeholders were highly engaged. Significant thought had been given by the industry

participants interviewed as to how they would respond and the wider implications for their

industry. Further, there was significant acknowledgement of the role DIA had played in

ensuring a high level of engagement with industry.

A large share of the step-up in investment initiated by the reforms will be capital in nature

i.e. investing in upgrading/enhancing the existing network and in new infrastructure. As such,

this formed a significant part of our focus for the interview process. In line with this, we note

that it is the “shock” created by a material step up in investment that is the focus of our CGE

modelling. The Affected Industries workstream explored how capital programmes are

delivered currently – with reference to the asset lifecycle. We then explored how delivery

In addition to the discussions held with industry participants, we interviewed representatives

might change under a scenario which combines an industry restructure expected to enable

from industry bodies and those with perspectives of the experience in New Zealand both in

clear market signalling of the medium to longer-term investment pipelines, and more

Water and Electricity distribution, and in Water in other jurisdictions. This provided further

sophisticated procurement alongside a significant increase in investment.

evidence/insight as to how the combination of structural and regulatory reform could

enhance the performance of the sector.

The other major area that we focussed on was the labour market impact from reform,

including the capacity constraints, skill shortages and possible solutions to help meet the

We also interviewed the New Zealand regulator (Taumata Arowai) and the Scottish regulator

significant increase in workforce required. Labour represents the key factor input into the

WICS, to understand perspectives on the anticipated process for New Zealand, and the

investment process, so access to a workforce at scale and with the skills necessary to deliver

actual experience in a jurisdiction that had undergone substantive reform.

the investment programme is critical.

under the Official Information Act 1982

Released

© 2021 Deloitte Access Economics

53

OVERVIEW OF AFFECTED INDUSTRIES

Methodology

Targeted stakeholder interviews were validated against case studies, and four criteria: supply chain, labour

market, access to capital, and innovation and productivity.

Targeted stakeholder interviews

Validate against case studies and criteria

Implications and considerations

Targeted stakeholder interviews

Testing and validating stakeholder information

Implications and considerations

Targeted interviews were undertaken to assist with

We tested and validated the information collected

Information from stakeholder interviews was

developing an understanding of the impact of

through stakeholder interviews against local and

synthesised to develop a narrative of the

reform on industries, and potential policy

international case studies, and criteria.

consequences of reform.

implications.

International case studies included water reforms in

The following slides discuss the implications of the

Interview questions were directed at assessing how

Australia and Scotland.

reform on each criteria, and highlight key

stakeholders participate in the sector currently and

Local case studies included the New Zealand

constraints and risks.

how they are responding, or planning to respond,

electricity sector reform, and the experience of

The narrative provided through the interviews has

to the reforms. We also tested perspectives on

Watercare in Auckland.

been developed to complement the economic

potential efficiencies or opportunities that could

impact assessment and highlight consequences for

arise, and challenges or constraints they envisage as

Taumata Arowai provided perspectives as to how it

specific sectors.

a result of the reform.

saw the role would impact investment priorities and,

in particular, drinking and wastewater.

We shared questions with participants in advance of

the interviews to ensure a more informative and

We considered the following criteria for each:

under the Official Information Act 1982

targeted conversation.

• Supply chain

• Labour market

• Access to capital

• Innovation and productivity

Released

© 2021 Deloitte Access Economics

54

11. Industry Structure

under the Official Information Act 1982

Released

© 2021 Deloitte Access Economics

55

INDUSTRY STRUCTURE

Overview of Post-reform Industry Structure

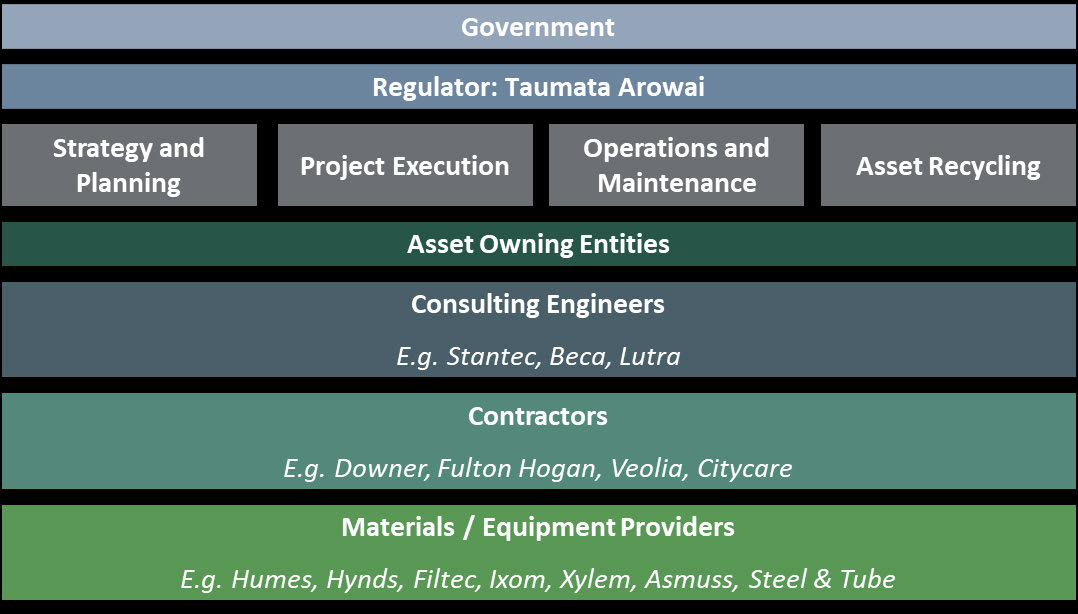

The water industry is comprised of many different participants, spanning multiple sectors.

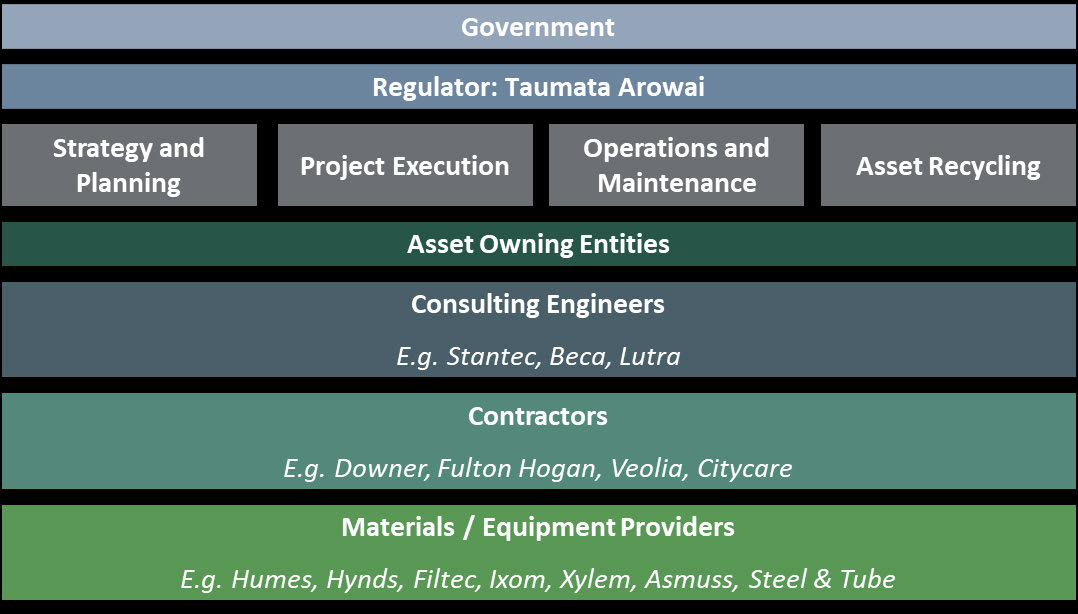

Water industry structure

How will things change post-reform?

• Councils who participate in the reforms will no longer control water assets for their

regions. For some, this will mean a significant change in their operating roles and

reduction in workforce, and a risk that valuable water sector capability could be lost

through the transition process. The local and regional impact of this is expected to be

more than offset by the investment in regions by the new entities.

• Engineering firms will scale up the number of employees operating in the water sector,

although there are issues with finding skilled labour (discussed further below). Clearer

pipelines of work should allow these firms to have confidence investing in on-the-ground

capabilities. There is some concern that fewer water entities could see more work overall

but for a reduced number of consultancies. There is also some apprehension about

the transition-period.

• Contracting firms expect to see a bigger workforce and a greater focus on compliance

areas, given the new regulatory environment. Improved procurement processes will

smoothe operations for these firms and allow work to get underway faster. International

firms expect to draw on offshore expertise and technology, but will still need to deploy

large numbers of people on the ground where the assets are.

• Material and equipment providers are already scaling up in some cases in preparation for

under the Official Information Act 1982

reform, but are nervous about the transition process. There will be potential for better

integration of the materials and equipment supply chain into the design process, aligned

with more integrated contracting processes. This is likely to be particularly the case in

relation to the more effective use of specialist equipment – for example the use of

advanced telemetry equipment to detect network issues, and to facilitate the most

efficient use of water.

Released

© 2021 Deloitte Access Economics

56

INDUSTRY STRUCTURE

Overview of Industry Structure

Below is a list of companies and sector bodies we interviewed as part of the engagement process.

#

# Employees

# Employees in

Entity

Profile

Employees

New

Water Services

Globally

Zealand

New Zealand

Asmuss

Specialises in polyethylene and steel piping, fittings and valves.

N/A

230

N/A

Beca

Focused on long-term, sustainable solutions for Three Waters.

N/A

N/A

N/A

Citycare Water

Provider of construction, maintenance and management services across New Zealand.

N/A

1,450

N/A

Downer

Has a presence in the design, build and operation phases for the water sector.

N/A

13,000

450

Filtration Technology

Design advanced engineering systems and cost-effective solutions to water and wastewater problems.

70

60

60

Humes

Deliver smart, sustainable solutions for water by providing innovations in pipe manufacturing.

640

270

245

Ixom New Zealand

Chemical supplier predominately based in Australia and New Zealand.

1,000

300

75

Lutra

Suppliers for containerised treatment plants, and compliance reporting and monitoring tools.

N/A

30

30

Stantec

International professional services firm in the engineering design and consulting industry.

22,000

600

200

Steel and Tube

Providers of steel products.

N/A

1,000

N/A

under the Official Information Act 1982

Taituarā

National membership organisation for Local Government professionals.

N/A

N/A

N/A

Veolia

A mixed business mainly involved in the operation of plants, with a small focus on construction.

179,000

300

N/A

Water New Zealand

The industry body for the Three Waters sector.

N/A

N/A

N/A

Watercare

New Zealand’s largest water supplier.

N/A

984

N/A

Released

Xylem Water Solutions

Technology-based water solutions business providing UV disinfectant and biological water treatment solutions.

15,000

22

22

© 2021 Deloitte Access Economics

58

INDUSTRY STRUCTURE

Overview of Industry Structure

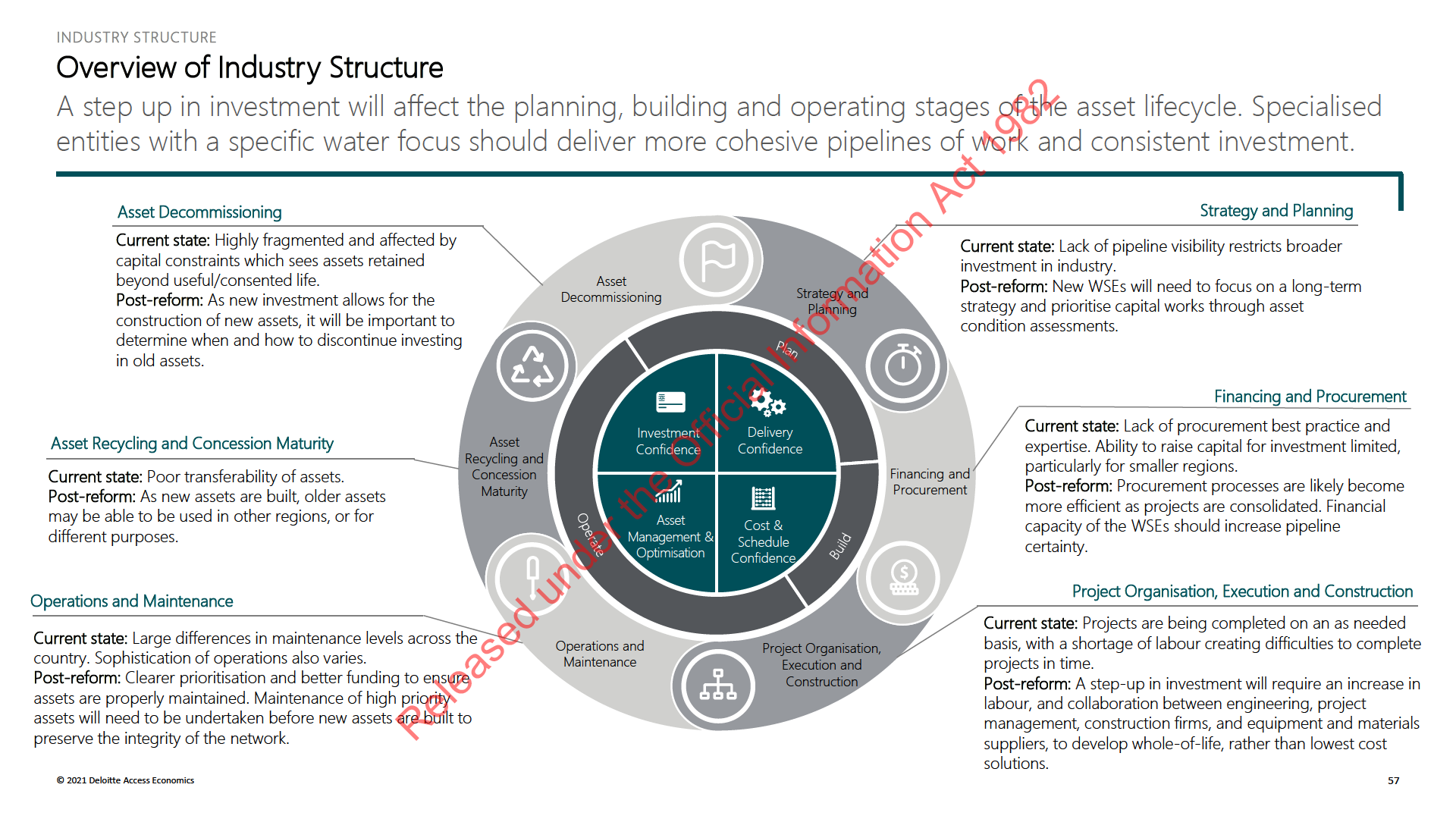

The water industry is comprised of many different participants, spanning multiple sectors.

We have looked to map the participants interviewed to the ANZSIC classifications referred to in our economic modelling. The economic modelling aggregates the following classifications up to

the sector level to determine gains/losses in each sector and region. We note that the activities of some participants – in particular, consulting engineers – will span a range of activities. The

ANZSIC classifications align with those in our CGE model.

Stage of life cycle

ANZSIC classification

# of employees

per classification

Sector level

Players

Strategy and planning

• WaterNZ, Taumata Arowai.

• Professional, Scientific & Technical services

• 189,000

• Professional

services

Watercare, Wellington Water

Financing and

• Local Councils, Watercare,

procurement

• Professional, Scientific & Technical services

• 189,000

• Professional

services

Wellington Water

• Primary Metal and Metal Product Manufacturing

• 4,100

• Machinery and Equipment Manufacturing

• 29,300

• Heavy

Project organisation,

• Veolia, Ixom, Humes, Hynds,

• Water Supply, Sewerage and Drainage Services

• 2,150

manufacturing

execution and construction

Xylem, Filtration Systems, Beca,

• Waste Collection, Treatment and Disposal Services

• 7,100

• Water

Stantec, Lutra

• Construction Services

• 101,600

• Construction

• Heavy and Civil Engineering Construction

• 37,800

Operations and

under the Official Information Act 1982

• Water Supply, Sewerage and Drainage Services

• 2,150

• Water

• Citycare, Fulton Hogan,

maintenance

• Waste Collection, Treatment and Disposal Services

• 7,100

• Electricity

Downer, Stantec

Asset recycling and

• Waste Collection, Treatment and Disposal Services

• 7,100

• Water

concession maturity

• Heavy and Civil Engineering Construction

• 37,800

• Electricity

• Local Councils

Released

Asset decommissioning

• Local Councils, Watercare,

Wellington Water

© 2021 Deloitte Access Economics

59

12. Supply Chain

under the Official Information Act 1982

Released

© 2021 Deloitte Access Economics

60

SUPPLY CHAIN

Supply Chain

The water supply chain comprises a mix of materials, plant and equipment and labour.

Water Sector Supply Chain Breakdown by % of Cost

Project Pipeline typically

involves a mix of:

Labour

Materials

• Simple renewals

Consultants / Managers

Contractors

Materials / Plant / Equipment

• Complex renewals

@ 50%

@ 50%

• Pump stations / Treatment

station upgrades

• Reservoir upgrades

• Major projects

Water Entity / Consultants

Contractors

Materials / Plant /

Percentage

Makeup of workforce

Makeup of workforce

Equipment

of

cost

Graduate Engineer

Construction Manager

Materials

50%

Engineers

Construction Supervisor

Plant and Equipment

50%

Senior Engineers

Technicians

Principal Engineers / Senior /

Advanced Specialists

Heavy Vehicle Drivers

under the Official Information Act 1982

Programme Leads / Project

Skilled Labourers

Managers

Labourers

Project Directors / Senior Project

Managers

Trainee/Apprentices

Released

30% to 40% of FTEs1

60% to 70% of FTEs2

© 2021 Deloitte Access Economics

1 Excludes procurement and wider back office admin and support FTEs.

61

2 It is estimated that @35% to 40% of the workforce wil comprise labourers/skil ed labourers/trainees and apprentices

SUPPLY CHAIN

Supply Chain

Improved visibility of the work pipeline will lead to a scaling up of operations with associated benefits.

There is an expectation that the increased scale and related funding capability of the

• Scale benefits – higher spend across fewer/more standardised requirements;

proposed new WSEs will change supply chain arrangements. We tested with industry

participants the benefits of greater visibility to the pipeline of work, and the extent to which

• Standardisation of parts and materials used to improve purchasing power;

that would drive changes/encourage suppliers to scale up or innovate. We also discussed

• Greater specialisation of procurement services; and

industry structure and the extent to which changes to the sector would encourage new

• The potential for smaller scale operators to be squeezed out as a result of the

entrants/overseas participants with a small footprint currently to scale up. We also canvassed

procurement processes that the WSEs might adopt, reducing diversity in the supply chain.

issues of capacity constraints in the supply chain and the flow-on implications for costs and

efficient planning.

Short-term Covid-19 disruption

As the industry model and procurement practices mature post the transition period, it is

Some participants noted the supply chain disruption caused by Covid-19. These issues

expected the following will occur:

include extended lead times for materials; ports, freight and shipping issues; and increased

prices for materials. While some of disruption is expected to be relatively short term, it has

• Industry consolidation is likely to happen through parts of the supply chain as the new

exposed a vulnerability in the supply chain for certain materials (e.g. it is difficult to get some

WSEs increase the scale at which they procure and move to refine their supply chain

chemicals involved in water purification). This could drive a preference to reduce reliance on

arrangements;

offshore inputs. Consolidation of suppliers post-reform may increase vulnerabilities

• New entrants are likely, particularly major organisations which have a significant presence

where reliance remains on, or shifts to offshore inputs.

in Australia but who are not currently present in New Zealand ;

• The scaling up of local operations by participants with an existing presence in New

Zealand – a number of major industry participants (Suez, Veolia etc) and international

consultancies and service providers, have some footprint in New Zealand currently and all

under the Official Information Act 1982

are well-informed as to the reform programme and the

related implications/opportunities;

• While new/scaled up entities may bring new capability, it is likely scaling up could involve

the acquisition of local entities or capability;

• New business models, particularly between the water entities and service providers;

Released

© 2021 Deloitte Access Economics

62

SUPPLY CHAIN

Supply Chain

Changing procurement processes should help reduce 'lumpy' supply chains.

Opportunity to learn from the past

Contractors don't want to be carrying/funding large stores of materials. However,

There are significant concerns with current government procurement processes in the water

they cannot afford to have parts of their workforce standing idle, because required materials or

sector. The expectation is that current practices will not roll over into the new entities;

equipment is not to hand. The more certainty they have as to the timing and nature of the capital

otherwise gains anticipated from the establishment of the WSEs may be much harder to

programme, the better they are able to coordinate their logistics, and in turn generate cost

achieve.

efficiencies and reduced capital requirements.

Interviewees were not concerned as to the ability of the supply chain to scale up from a materials

Current procurement practices – with the heavy emphasis on cost as opposed to

and equipment perspective. Domestic capacity was not generally identified as an issue. However,

whole of life value – create significant risk. Similarly, the lumpy nature of the work

a concern was raised as to the risk that some aspects of the domestic supply chain depend on a

programme makes it difficult for small to medium size organisations to maintain

limited number of mid-scale providers, and if these entities exited the market there would be no

viability, notwithstanding the fact that some are considered critical to the overall supply

domestic capability to fill the gap. However, lumpiness or uncertainty associated with the project

chain.

pipeline was identified as a more significant issue, and a factor contributing to the potential loss of

mid-sized domestic capability.

As part of the interview process, reference was made to the ability of industry generally to

respond to a material increase in demand. The response to the Christchurch earthquakes

The water industry internationally is relatively homogenous from a materials and equipment

was cited as an example of a step-up in investment of a comparable scale to that envisaged

perspective – there is nothing particularly unique that sets New Zealand's needs apart from that

by the water reform process. In this context, it was noted that given the urgency of the

of other jurisdictions. Further, providers of materials and equipment have sophisticated inventory

response, contractual arrangements/procurement practices were not always optimal.

management and logistics arrangements in place, which should mean an ability to respond

Lessons from this experience that can be applied to water reform, given its planned nature

relatively easily to any step-up in demand.

and longer timeframe.

New Zealand is a small market by international standards. A significant increase in investment in

this market is unlikely to have any major impact on the ability to access materials and equipment,

under the Official Information Act 1982

Increased visibility of pipeline is the key driver of procurement improvements

over and above the more generic challenges the country faces by virtue of its scale and location.

A key expected benefit of reform from a supply chain perspective will be

We note that the supply chain both domestically and globally will continue to evolve. For

improved procurement and pipeline management processes, which the WSEs are expected

example, Veolia is currently seeking to acquire Suez. That transaction, if successful, would create a

to implement. The ability to contract at scale with certainty and over a longer timeframe

global entity comprising circa 250,000 people.

has potential benefits in the form of inventory and working capital management, which in

turn flows through to the efficiency of workforce management and project delivery.

Similarly, as the industry works through near term issues with the transition and immediate capital

Released

priorities, there will be an increased focus on the more consistent adoption of new technologies

and related equipment. This change in demand will flow through to the supply chain.

© 2021 Deloitte Access Economics

63

13. Workforce

under the Official Information Act 1982

Released

© 2021 Deloitte Access Economics

64

WORKFORCE

Workforce characteristics

Reform provides an opportunity to address current workforce issues and to reposition the water sector as

a strong career opportunity – but this will take time and there will be near term challenges

The delivery of water services and the related capital expenditure required to sustain and

Labour and related direct costs – in their various forms – is the largest cost input into capital

expand water infrastructure is labour intensive. The material rise in capital

works by a substantial margin, representing an estimated 50% of total costs currently

expenditure anticipated from reform is expected to have implications for both employment

(excluding the labour content of the materials and equipment component of the supply

and the structure of the labour market.

chain, which is also significant).

As part of our interview process, we explored expectations around employment and the

A typical investment process involves the following four elements: investigation, concept,

need for increased skills development and specialisation. We also discussed expectations and

design, and build

concerns in relation to capacity and capability constraints, productivity concerns, and the

It is only in the “build” phase that materials and equipment are a major input, although these

importance of being able to access offshore talent.

represent a large cost component at that stage.

Workforce

However, even in the build phase, the labour component is still likely to represent roughly

20% to 30% of the total cost, though this will vary significantly depending on the nature of

The water sector workforce is complex, and spans multiple industries and disciplines, each

the asset being created. Renewals and minor capital works – which comprise a large

with their own dynamic. Further, different structures currently apply across local authorities.

component of the immediate investment requirements of the sector are considerably more

In particular, all Councils use a combination of in-sourced and out-sourced provision, but the

labour intensive than major capital projects. As such, a relatively greater proportion of that

nature of those arrangements varies widely.

labour component is delivered on location.

A significant part of local authorities’ workforces and third-party contractors are deployed to

A number of interviewees noted that even with the most efficient and innovative processes

support the sector currently. Estimates of the total workforce employed by Councils in the

the need for a significant workforce on hand is unavoidable. Therefore, any significant step-

sector are in the range of 4,000 – 5,000. The Water New Zealand National Performance

up in investment will also require an increase in the size of a workforce that is already under

Review 2019-20 (the Review) provides the following analysis of the Council workforce

pressure.

under the Official Information Act 1982

dedicated to the provision of water services. Most, but not all, Councils participate in the

The sector is experiencing a workforce shortage, which is likely to be exacerbated given

Review. All the large Councils and specialist council-owned providers such as Watercare and

increasing regulatory pressures and community expectations, that will drive an uplift in

Wellington Water participate.

Council expenditure.

Workforce Participant

Number

The number of qualified staff needed to deliver capital works is already under stress due to a

lack of overseas resources, increasing remuneration expectations and other opportunities in

Full-time employees

2,745

the wider construction sector. The contractor market is currently sized to reflect historic

Contractors

1,196

Released

delivery requirements. The workforce is expected to be squeezed further as spending on

Total

3,941

Three Waters projects, shovel ready infrastructure projects, climate change and RMA reforms

65

Source: Water New Zealand

increase nationally.

WORKFORCE

Workforce composition and substitution

The change in the workforce required to deliver the investment envisaged under the modelled scenarios.

Information as to the composition of the current workforce is limited – complicated by the

One opportunity cited related to the Oil and Gas sector. While this sector has scaled back,

fact that the water sector supply chain comprises multiple industries. We understand there

there are several providers in areas such as Taranaki that have specialist piping skills and

are projects underway that are expected to improve this understanding. This makes it difficult

solutions that would be transferable to the Three Waters sector. However, there is a risk this

to accurately estimate the nature and scale of the expansion in the workforce required to

capability could be lost if the step-up in Three Waters activity doesn't coincide with the

deliver the capital investment programme envisaged by reform, and develop an appropriate

scaling down of activity in traditional areas of focus.

response.

We have attempted to estimate the increase in the workforce required to deliver the

Our Australian colleagues also noted that they have seen some success with shared

projected investment under the core scenarios modelled. This estimate is illustrative only and

services models across similar industries, for example sharing a workforce across electricity or

intended to provide an indication of the scale of change.

fibre providers where sensible.

Based on data and analysis derived from other water sector projects we have calculated a

high level estimate that it takes approximately 800 FTEs to deliver $300 million of capital

Efficiency/substitution

projects. On this basis and assuming an increase in annual investment by @ $1.4 billion to

100%

90%

80%

70%

60%

50%

$2.9 billion – being the estimated annual average difference spend under the system

FTE al ocation by discipline/skill

transformation scenario versus the counterfactual – this could see the need for an additional

2,900 to 5,700 FTEs, on average, each year. This includes the water sector and the wider

Planners / Consultants

30%

1,720

1548

1376

1204

1032

860

water supply chain. This assumes an average annual investment differential of $2.15 billion to

Managers / Contractors 70%

4,013

3612

3211

2809

2408

2007

deliver the capex envisaged, as set out in the table to the right.

Total

5,733

5,160

4,587

4,013

3,440

2,867

It is important to note this is not the potential total increase in FTEs, but rather the difference

under the Official Information Act 1982

between the system transformation and counterfactual scenarios (i e. the average change in

FTEs). Further, this is related to the estimated number of FTEs needed to deliver the

increased investment programme, not to any flow-on employment impacts of reform.

The efficiency/substitution factor included in the table reflects an assumption that a

combination of better workforce practices and substitution – i.e. workers moving to the

sector from adjacent roles will partially offset the expansion in the workforce required.

Released

© 2021 Deloitte Access Economics

66

WORKFORCE

Workforce risks

The increase in the required workforce estimated in the previous slide does not fully reflect the scale of

change that will occur, or the risks that need to be recognised and mitigated, through the transition.

While the skills of the current workforce will be needed, not all current roles will map neatly

There are concerns as to the capacity of the workforce to meet the demand

to those available in the new WSEs or industry. There may be a need for some in the sector

signalled through the current Council LTP process. Further, providers have indicated a

to take up alternative roles and possibly shift locations. This factor, combined with the

wariness about resourcing to meet that demand due to a concern as to the potential for a

relatively older age profile of the Council workforce, creates a significant risk that capability

“boom/bust” cycle of investment, whereby following a burst of spending by Councils there is

could be lost through the transition process. In some regions, it is likely that considerable

something of a hiatus as the new water entities work through their planning and

information on matters such as the location and condition of assets is held through the

prioritisation processes.

institutional knowledge of the existing workforce. There is a risk that knowledge will be lost

through the transition process as the current workforce retires.

The most immediate pressure points are likely to be specialist water consultancy expertise,

which is seen as scarce and “boots on the ground” labour. Several interviewees noted

Further, there are other wider risks to smaller Councils that will need to be managed. For

that migration policies (once borders re-open) could help mitigate skill shortages in the near-

example, some technical and leadership roles are shared positions that cover a range of

term, but 'growing our own' was viewed as preferential. Again, reference was made to

Council activities, rather than just water. A move to WSEs could see that capability lost either

the Christchurch experience and the significant reliance placed on imported labour.

to the WSEs, Councils, or industry. Further, the supply chain that Councils engage with on

water related matters brings innovation and capability that can have wider applicability

across Council operations.

Based on experience in other sectors and jurisdictions it is expected the composition of the

workforce will change. There is likely to be proportionally less employment in the WSEs, due

to a combination of efficiencies that can be expected over time from the consolidation of

under the Official Information Act 1982

management structures, and systems and processes, combined with efficiencies that will be

expected from improvement in the performance of the underlying asset base as this is

replenished/enhanced. On the other hand, it is expected that there would be a step-up, both

proportionately and in absolute terms, through the supply chain in response to the increased

level of investment anticipated.

Released

© 2021 Deloitte Access Economics

67

WORKFORCE

Workforce: Career pathways

Industry participants and sector bodies consider that there is a relatively low awareness of career

opportunities and little in the way of sector driven training and development.

Industry participants and sector bodies consider that there is a relatively low awareness of

Given the feedback from stakeholders around skilled labour shortages, we expect that the

career opportunities and little in the way of sector driven training and development. This

labour profile will be lumpier and less predictable than our core scenarios imply. There are

situation is compounded by the current industry structure and its fragmented approach to

clearly existing challenges in filling roles and meeting current demand in the workforce.

procurement. This restricts the ability to develop the industry standard competencies that

However, we note that access to labour was not identified as a long-term constraint in any of

various organisations such as Water New Zealand and Engineering New Zealand are

the case studies referred to below.

currently working on.

Growth in the labour force is likely to take a number of years (Taituara estimates five to 10

While articulating career opportunities supported by a focus on training pathways could

years given the training pathways involved) to respond to increased demand, and absorb

mitigate some labour supply challenges, there are significant risks in the near term that could

current skill shortages, in order to start seeing a meaningful step-change in employee

dilute the benefit of these initiatives. In particular, as borders open – particularly with

numbers. This means that efficiency gains in the labour market may take some time to be

Australia – there is a risk parts of the trained/skilled workforce may move offshore to better

realised fully.

remunerated opportunities. This situation could be compounded as borders with Australia

Pressure on the water workforce is not just a challenge for New Zealand. There is evidence

have re-opened before those with other countries such as South Africa, the UK and Ireland,

from other jurisdictions such as the US that there are critical staff shortages in the workforce

which have previously been large sources of both skilled and semi-skilled labour.

that provides drinking water and wastewater services – a situation likely to be compounded

“In Victoria the creation of regional water entities created much better

as a relatively older workforce starts to retire. Initiatives are underway to address this issue

career paths for workers in the industry. It enabled them to specialise in

which could be referenced as part of any process for developing a workforce plan for New

Zealand. For example, America's Water Workforce Initiative is a combined initiative involving

the water industry (rather than being a Council employee and having to

the Environmental Protection Agency and other federal agencies working with states, utilities,

do to a bunch of other things) plus it meant that rather than having to

tribes, local government and other stakeholders to address workforce issues.

under the Official Information Act 1982

move from one small Council to another to progress their career (which

Reform provides an opportunity to take a more proactive and longer-term approach to

often meant relocating) career path opportunities within in new (larger)

addressing workforce challenges. A combination of a better articulation of career

organisation became much more available.”

opportunities, the changing nature and increased sophistication of the roles/emerging roles

available and the scale of the investment going in to the water sector creates the prospect of

A further issue is the changing nature of the skills required of the workforce. This is driven in

elevating the status of a career in the water sector. This would see a flow through to the

part by the changing nature of the technologies required to run water utilities – including

ability to attract both domestic and international talent in both the core water sector and the

advanced monitoring and treatment technologies and information management systems.

associated supply chain.

Released

© 2021 Deloitte Access Economics

68

14. Capital Requirements

under the Official Information Act 1982

Released

© 2021 Deloitte Access Economics

69

CAPITAL REQUIREMENTS

Capital Requirements – New water entities