22 November 2024

Ref: DOIA-REQ-0005781

P Robins

Emai

l: [FYI request #28937 email]

Tēnā koe P Robins

Thank you for your email of 27 October 2024 to the Ministry of Business, Innovation and Employment

(MBIE) requesting, under the Official Information Act 1982 (the Act), the following information:

I request briefings:

2425-1012

2425-0749

BRIEFING-REQ-0002936

BRIEFING-REQ-0002687

Please find attached two of the requested briefings, with some information withheld under the following

sections of the Act:

9(2)(a)

to protect the privacy of natural persons, including that of deceased natural

persons;

9(2)(f)(iv)

to maintain the constitutional conventions for the time being which protect the

confidentiality of advice tendered by Ministers of the Crown and officials; and

9(2)(g)(i)

to maintain the effective conduct of public affairs through the free and frank

expression of opinions by or between or to Ministers of the Crown or members of

an organisation or officers and employees of any public service agency or

organisation in the course of their duty.

MBIE is withholding the remaining two briefings in full (including the titles) under section 9(2)(f)(iv) of the

Act, both briefings concern ongoing decisions yet to be undertaken by the Minister and Cabinet. Details of

the documents are provided in the table below.

#

Description/Title

Withholding

grounds

2425-1012 [

Title withheld]

Withheld in full,

including title,

under 9(2)(f)(iv)

1

2425-0749 Review of the Product Safety Policy Statement: Foam-filled furniture

9(2)(g)(i)

2

BRIEFING-REQ-0002936 Abuse in Care Royal Commission recommendations on

9(2)(a),

the Accident Compensation Scheme

9(2)(f)(iv)

4

BRIEFING-REQ-0002687 [

Title withheld]

Withheld in full,

including title,

under 9(2)(f)(iv)

I do not consider that the withholding of this information is outweighed by public interest considerations

in making the information available.

If you wish to discuss any aspect of your request or this response, or if you require any further assistance,

please contact

[email address]. You have the right to seek an investigation and review by the Ombudsman of this decision. Information

about how to make a complaint is available at

www.ombudsman.parliament.nz or freephone 0800 802

602.

Nāku noa, nā

Zoreen Ali

Manager Ministerial Services

Building, Markets and Resources

BRIEFING

BRIEFING

Review of the Product Safety Policy Statement: Foam-

filled furniture

Date:

20 September 2024

Priority:

Medium

Security

Tracking

In Confidence

2425-0749

classification:

number:

Action sought

Action sought

Deadline

Hon Andrew Bayly

Either

4 October 2024

Minister of Commerce and

Consumer Affairs

Agree to continue the Product

Safety Policy Statement: Foam-filled

furniture.

Or

Agree to revoke the Product Safety

Policy Statement: Foam-filled

furniture.

Contact for telephone discussion (if required)

Name

Position

Telephone

1st contact

Glen Hildreth

Manager, Consumer Policy 04 901 0687

Chris Cuthbertson

Policy Advisor

04 901 8301

✓

The following departments/agencies have been consulted:

Ministry for Regulation, Fire and Emergency New Zealand, MBIE Consumer Services

Minister’s office to complete:

Approved

Declined

Noted

Needs change

Seen

Overtaken by Events

See Minister’s Notes

Withdrawn

Comments:

RELEASED UNDER THE OFFICIAL INFORMATION ACT 1982

BRIEFING

BRIEFING

Review of the Product Safety Policy Statement: Foam-

filled furniture

Date:

20 September 2024

Priority:

Medium

Security

Tracking

In Confidence

2425-0749

classification:

number:

Purpose

To provide you with the report of the Product Safety Policy Statement: Foam-filled furniture review

(the

Report) and seek decision on continuing the Policy Statement.

Recommended action

The Ministry of Business, Innovation and Employment recommends that you:

a

Note that we have conducted a review of the Product Safety Policy Statement: Foam-filled

furniture, as required under section 30B of the Fair Trading Act 1986.

Noted

b

Note that we recommend continuing the Policy Statement.

Noted

EITHER

c

Agree to continue the Product Safety Policy Statement: Foam-filled furniture.

Agree / Disagree

OR

d

Agree to revoke the Product Safety Policy Statement: Foam-filled furniture.

Agree / Disagree

e

Note that your decision must be published on MBIE’s website.

Noted

RELEASED UNDER THE OFFICIAL INFORMATION ACT 1982

Glen Hildreth

Hon Andrew Bayly

Manager, Consumer Policy

Minister of Commerce and Consumer

Affairs

20 September 2024

..... / ...... / ......

2425-0749

In Confidence

1

Background

1.

In 2019, the Minister of Commerce and Consumer Affairs published the Product Safety

Policy Statement: Foam-filled furniture (the

Policy Statement) under section 30A of the

Fair Trading Act 1986 (the

FTA). Section 30B of the FTA requires us to review policy

statements every five years. Accordingly, we reviewed the Policy Statement and have

provided you with a report setting out our recommendations.

2.

The Policy Statement provides non-binding guidance for manufacturers, importers and

retailers of foam-filled furniture products. The intention behind the Policy Statement was to

address concerns about the combustibility and ignitability risks of residential foam-filled

furniture (

FFF) containing flexible polyurethane foam (

FPUF).

3.

It set the expectation with importers and manufacturers of FFF that they:

a.

measure the fire resistance of FFF (e.g. time it takes for furniture to ignite); and

b.

consider the fire resistance of FFF against applicable standards and international

regulatory requirements.

4.

It also set expectations that retailers inform consumers about:

a.

the fire resistance of FFF; and

b.

additional information regarding features in relation to fire safety.

Review of the Policy Statement

5.

We carried out a review to understand what changes, if any, had been made in response to

the Policy Statement.

Industry response has been limited

6.

Consultation with retailers, manufacturers and suppliers of FFF indicated the industry

response to the Policy Statement has been limited.

7.

One major retailer of FFF indicated that wool, which is naturally more fire resistant than

FPUF, has become a large part of their business and a component of their furniture. Other

industry stakeholders did not follow the Policy Statement’s guidance, either because of a lack

of awareness of the Policy Statement, or the costs of adhering to the guidance are

uneconomical.

8.

There has been minimal adoption of technologies to increase fire resistance of FPUF since

the Policy Statement was released.

It is unclear how effective the Policy Statement has been

9.

Fire deaths have not reduced consistently since the Policy Statement was published.

10. Although five years is a short time to expect to see change in these measures, the limited

RELEASED UNDER THE OFFICIAL INFORMATION ACT 1982

industry response suggests that the Policy Statement has not been effective at reducing risks

posed by FFF.

2425-0749

In Confidence

2

Limitations of the review

11. Repeated attempts to contact a major manufacturer of FPUF and FFF was met with no

response. Furthermore, we focused on the industry response, rather than how consumers

had responded, as the Policy Statement was aimed at manufacturers, suppliers and retailers.

12. s 9(2)(g)(i)

We therefore had to rely on existing data and research and have not

commissioned any new research in carrying out this review. Furthermore, existing research

and data on causes of fires in New Zealand, and statistics on house fires and associated

deaths and injuries are limited and not regularly published in any detail.

Conclusions and recommendations

13. It is unclear what role FPUF plays in residential fires and fire deaths in New Zealand. Based

on the information we do hold, it appears unlikely the Policy Statement has reduced risks of

death and injury, and it is unclear whether it will do so in the future.

14. Section 30B of the FTA requires that following a review, we recommend the Policy Statement

be either:

a.

continued

b.

amend

c.

revoked

d.

replaced.

15. We have assessed the above options against their likelihood to minimise risk of deaths,

injuries and damage to residential property, while minimising costs to industry consumers

and society as a whole.

16. There is insufficient information to suggest what, if any, amendments to the Policy Statement

could be made to improve these outcomes. Similarly, there is insufficient information to

suggest what the Policy Statement could be replaced with. Accordingly, we have ruled out

those two options.

17. Continuing or revoking the Policy Statement appear to be viable options.

18. While it is unclear whether the Policy Statement has had a material impact on the minimising

risk of deaths, injuries or damage to residential property, nothing suggests it has increased

these risks. Continuing the Policy Statement is therefore unlikely to have a negative impact

on this outcome, and it does not impose significant costs on anyone.

19. It is also difficult to assess the impact of revoking the Policy Statement. If the Policy

Statement has had no material impact on minimising harm, then revoking it is unlikely to

have an impact. However, as it is the primary piece of guidance available to manufacturers

RELEASED UNDER THE OFFICIAL INFORMATION ACT 1982

and retailers, increasing the awareness of the Policy Statement may increase its impact.

20. We consider that there may be merit in retaining the Policy Statement for at least a further

five years.

2425-0749

In Confidence

3

Consultation

21. The Ministry for Regulation stated there is conflicting evidence between the impact of FFF on

fires in New Zealand when compared internationally, and questioned whether more can be

done to resolve such uncertainty around the data by working with FENZ.

22. Should you agree to continue the Policy Statement, we will work with FENZ on what actions

they can take to gather more information regarding the impact of FFF on fires in New

Zealand. This will help inform a future review of the Policy Statement.

Next steps

23. The Policy Statement and Report are annexed to this briefing for your consideration.

24. As a product safety policy statement is a non-binding guidance document and has a

relatively narrow focus, MBIE does not consider Cabinet approval is required for continuing

or revoking the Policy Statement.

25. The FTA requires your decision to be published on MBIE’s website. We wil arrange this and

liaise with your office.

Annexes

Annex 1: Product Safety Policy Statement: Foam-filled furniture

Annex 2: Review of Product Safety Policy Statement: Foam-filled furniture

RELEASED UNDER THE OFFICIAL INFORMATION ACT 1982

2425-0749

In Confidence

4

Annex 1: Product Safety Policy Statement: Foam-filled furniture

RELEASED UNDER THE OFFICIAL INFORMATION ACT 1982

2425-0749

In Confidence

5

Product Safety Policy Statement

Product Safety Policy Statement

Foam-filled furniture

Reducing the risk of fire-related harm from household

furniture products

This product safety policy statement is issued by the Minister of Commerce and Consumer

Affairs pursuant to section 30A of the Fair Trading Act 1986

Hon Kris Faafoi - Minister of Commerce and Consumer Affairs

On this day being: 17 July 2019

RELEASED UNDER THE OFFICIAL INFORMATION ACT 1982

Introduction

This Product Safety Policy Statement is made by the Minister of Commerce and Consumer

Affairs under section 30A of the Fair Trading Act 1986. It is being issued with the expectation

that manufacturers and retailers will ensure their foam-filled furniture products are safe for

consumers to have in their living spaces.

This Product Safety Policy Statement highlights the risks associated with foam-filled furniture

as a class of goods. It provides guidance for manufacturers and retailers on reducing the risk of

harm to consumers from fire, when foam-filled furniture is involved.

The Ministry of Business, Innovation and Employment (MBIE) will review this Product Safety

Policy Statement within two years of being issued and report to the Minister of Commerce and

Consumer Affairs.

Policy Statement approach and intention

A Product Safety Policy Statement enables industry to self-adjust, by establishing an expected

safety benchmark for the goods that are subject of the statement. The intention is that the

Product Safety Policy Statement will address the identified safety issues with those goods,

without more formal regulatory intervention being required. There are two policy objectives

underlying this Product Safety Policy Statement: to minimise deaths, injuries and damage to

property, while also minimising the costs to industry, consumers and society as a whole.

A Product Safety Policy Statement allows the industry to voluntarily follow guidelines and

create a positive change to help increase consumer safety. Product Safety Policy Statements

are a comparatively new approach to product safety in New Zealand. The success of the

approach will depend on the willingness of the industry to respond to voluntary guidelines.

MBIE recognises that tackling the risk to consumers emanating from foam-filled furniture

requires a coordinated and responsible approach by government, manufacturers, importers

and retailers working together. By working with the industry, MBIE hopes to guide the industry

to making changes within its supply chain and manufacturers that effectively decreases the

risk from foam-filled furniture.

Product Safety Policy Statements are a recent addition to the product safety regulatory regime

in New Zealand. The success of the Product Safety Policy Statement will depend on the

engagement of manufacturers and retailers in the development and implementation of

guidance, and the monitoring of its impact. MBIE will work with the industry to map out a

pathway to compliance between industry and MBIE, in order to decrease the number of

preventable fire deaths and injuries to consumers. This approach relies on the industry to

consider and, where necessary and practicable, to adjust its practices.

RELEASED UNDER THE OFFICIAL INFORMATION ACT 1982

2

MINISTRY OF BUSINESS, INNOVATION & EMPLOYMENT

PRODUCT SAFETY POLICY STATEMENT FOAM -FILLED FURNITURE

Definition of foam-filled furniture and scope of the

Product Safety Policy Statement

What is foam-filled furniture?

Flexible polyurethane foam (FPUF) is a common component in a wide range of furniture sold in

New Zealand. There are a number of risks associated with FPUF as it increases the

combustibility and ignitability of furniture. A number of injuries and fatalities have been

connected to the presence of FPUF.

The seating element of furniture often contains foams for added comfort. Other widely used

types of foam that fill furniture are made from:

Rubber-based biological material such as 100% natural latex derived from the sap of

the rubber tree; or

Petroleum–based chemicals such as polyurethane and synthetic latex (also known as

natural latex) derived through the process to make petroleum from crude oil; or:

Petroleum–based chemicals combined with biological material such as rubber or soy.

Foam can be measured by density and firmness:

Density can be measured by the weight of the foam per cubic metre/foot

Firmness, or Indentation Force Deflection, can be measured by the weight it takes to

compress the foam by one third

Scope of the Product Safety Policy Statement

For the purpose of this Product Safety Policy Statement, foam-filled furniture includes but is

not limited to residential furniture that has been designed for personal use in living spaces

such as houses, sleep-outs and baches, caravans and campervans, and recreational boats. This

includes but is not limited to couches and seats, and mattresses and sleeping swabs.

For the purpose of this Product Safety Policy Statement, foam-filled furniture does not include

commercial furniture that has been designed and tested for use in commercial settings.

There are a number of reasons why this Product Safety Policy Statement focuses on residential

settings. Consumers are more at risk in residential settings than in a commercial property,

because domestic premises often do not have to have sprinkler systems and fire extinguishers,

fire-resistant escape routes, or are smoke-free. Consumers are also more likely to be asleep in

their living spaces, further reducing the time available to escape from a fire. These factors

reduce the amount of time consumers have to get away from a property when fire ensues.

Safety issues relating to foam filled furniture

RELEASED UNDER THE OFFICIAL INFORMATION ACT 1982

Foam-filled furniture is a source of combustible material provides fuel in the event of a fire, as

it can:

catch fire easily

burn and spread quickly

give off toxic gases.

3

MINISTRY OF BUSINESS, INNOVATION & EMPLOYMENT

PRODUCT SAFETY POLICY STATEMENT FOAM -FILLED FURNITURE

an average 3-piece suite made with flexible polyurethane foam has the

combustible potential of 10 litres of fuel and is a high risk for harm or death

through burns and/or inhalation of toxic gases

Manager Fire Investigation, Fire and Emergency New Zealand

Consumers need time to get away from fire when it threatens their life. Petroleum-based

foam, such as FPUF, contain chemicals that increase the combustibility of a fire, increase the

and danger from the fire due to the:

Ease with which the chemicals ignite

Speed with which the chemicals cause the fire to burn

Heat energy the chemicals give off

Toxic gases, such as carbon monoxide and hydrogen cyanide, the chemicals produce

“If petroleum-based foam-filled furniture catches fire, vast amounts of flammable

fire gases are quickly released so that there is insufficient oxygen available to

support combustion in the room. This leads to superheated flammable and toxic

gases spreading throughout the building until they reach areas of fresh air. This

then ignites, and causes the fire to extend into rooms that were previously

untouched by the original source of the fire.”

Manager Fire Investigation, Fire and Emergency New Zealand

Coroner’s reports show that more people die of respiratory poisoning (ie through smoke

inhalation) than of burns from the flames themselves. From 2006 to 2016, 177 people died in

the course of avoidable residential structure fires. From 2012 to 2017 there were 1,227 fire-

related injuries.

Guidance for manufacturer, importers and retailers

This Product Safety Policy Statement provides guidance and establishes a product safety

benchmark for the goods that are the subject of the statement. This enables manufacturers

and retailers to self-regulate in the foam-filled furniture industry to increase consumer safety.

The guidance sets out:

a suggestion for a benchmark fire-resistance rating for foam-filled furniture

guidance on how retailers, manufacturers and MBIE can inform consumers on the

safety and fire-risks of foam-filled furniture

RELEASED UNDER THE OFFICIAL INFORMATION ACT 1982

a proposed mechanism for monitoring the impact of this Product Safety Policy

Statement on the product safety regulatory regime

4

MINISTRY OF BUSINESS, INNOVATION & EMPLOYMENT

PRODUCT SAFETY POLICY STATEMENT FOAM -FILLED FURNITURE

A benchmark fire-resistance rating for foam-filled furniture

Fire and Emergency New Zealand report that, prior to the introduction of FPUF, the time it

took for a New Zealand residential room to become fully involved in fire could take up to 30

minutes. With the introduction of FPUF to furniture this has reduced to 3-4 minutes.

By limiting the risk of ignitibility and combustibility of furniture, it is expected that the time

that people have to escape a house fire can be increased. By following the implementation

advice below, the furniture industry can contribute to fire safety. There are international

jurisdictions that have mandatory fire safety standards for furniture that can be consulted as

guidelines for the industry:

United Kingdom: Upholstered Furniture (Fire) (Safety) regulations (HMSO, 1988)1

State of California: Technical Bulletin 1162

Republic of Ireland: S.I. No. 336 – industrial Research and Standards (Fire Safety)

(Domestic Furniture) Order, 19883

Implementation advice for manufacturers and importers and

retailers of foam-filled furniture

Under the Consumer Guarantees Act 1993, goods supplied to a consumer must be of

acceptable quality. This includes a requirement that they must be safe. Under the Fair Trading

Act 1986, goods are considered unsafe if with reasonably foreseeable use (including misuse),

the goods will, or may, cause injury or harm to any person.

Manufacturers and importer

Manufacturers should consider the furniture as a whole. There are a range of ways to improve

fire resistance, such as the chemical composition of the foam in furniture, and the use of fire

resistant materials for fillings, interliners and outer covers.

To assist with the design, manufacture and sourcing of safer foams and materials for consumer

products, the standards listed below set out performance and test criteria for ignitability.

AS/NZS 3744.1 Furniture—Assessment of the ignitability of upholstered furniture.

Ignition source—smouldering cigarette

BS EN 1021-1 Furniture. Assessment of the ignitability of upholstered furniture.

Ignition source smouldering cigarette

BS 5852 Methods of test for assessment of the ignitability of upholstered seating by

smouldering and flaming ignition sources.

AS/NZS 3744.2 Furniture—Assessment of the ignitability of upholstered furniture.

Ignition source—match-flame equivalent

BS EN 1021-2 Furniture. Assessment of the ignitability of upholstered furniture.

Ignition source match flame equivalent

BS 5852 Methods of test for assessment of the ignitability of upholstered seating by

smouldering and flaming ignition sources.

RELEASED UNDER THE OFFICIAL INFORMATION ACT 1982

1 http://www.legislation.gov.uk/uksi/1988/1324/contents/made

2 http://www.bearhfti.ca.gov/industry/116.pdf

3 http://www.irishstatutebook.ie/eli/1988/si/336/made/en/print

5

MINISTRY OF BUSINESS, INNOVATION & EMPLOYMENT

PRODUCT SAFETY POLICY STATEMENT FOAM -FILLED FURNITURE

Manufacturers should measure the fire-resistance of foam-filled furniture, that is, the:

time it takes for furniture to ignite; and/or

temperature at which furniture produces a flashover (the sudden and rapid spread of

fire through the air).

Manufacturers, retailers and importers are encouraged to consider the performance of their

furniture against at least one of performance and test criteria referenced above.

Retailers

Retailers should inform consumers about the fire-resistance of foam-filled furniture.

Consumers should be provided with additional information regarding features in relation to

fire safety. Foam-filled furniture should have a fire-resistance rating that could be

communicated through:

Information on websites

Signs on furniture

Being told by the sales assistant

Written statement

Permanent labels on the furniture.

Monitoring and effectiveness

This Product Safety Policy Statement is intended to address concerns about the risks of

combustibility and ignitability of foam-filled furniture in household furniture.

It is understood that it may take some time for redesigned products to become available to

suppliers and consumers. Voluntary compliance with the Product Safety Policy Statement will

be monitored closely over the next two years, and feedback on its effectiveness will be sought

from the relevant stakeholders.

If the Product Safety Policy Statement is found to be ineffective in reducing the number of

injuries and incidents related to foam filled furniture, other measures under the Fair Trading

Act 1986 may be considered by the Minister. This may include regulations requiring

compliance with a mandatory product safety standard.

If you have any questions, see

https://www.consumerprotection.govt.nz/guidance-for-businesses/complying-with-consumer-

laws/understanding-product-safety/

or email

[email address].

RELEASED UNDER THE OFFICIAL INFORMATION ACT 1982

6

MINISTRY OF BUSINESS, INNOVATION & EMPLOYMENT

PRODUCT SAFETY POLICY STATEMENT FOAM -FILLED FURNITURE

Annex 2: Review of Product Safety Policy Statement: Foam-filled

furniture

RELEASED UNDER THE OFFICIAL INFORMATION ACT 1982

2425-0749

In Confidence

6

Review of the

Product Safety Policy

Statement: Foam-Filled Furniture

Report to the Minister of Commerce and

Consumer Affairs pursuant to section 30B of the

Fair Trading Act 1986

September 2024

RELEASED UNDER THE OFFICIAL INFORMATION ACT 1982

Permission to reproduce

Crown Copyright ©

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. To view a

copy of this license, visit

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

Important notice

The opinions contained in this document are those of the Ministry of Business, Innovation and

Employment and do not reflect official Government policy. Readers are advised to seek specific legal

advice from a qualified professional person before undertaking any action in reliance on the contents

of this publication. The contents of this document must not be construed as legal advice. The

Ministry does not accept any responsibility or liability whatsoever whether in contract, tort, equity or

otherwise for any action taken as a result of reading, or reliance placed on the Ministry because of

having read, any part, or all, of the information in this document or for any error, inadequacy,

deficiency, flaw in or omission from the document.

RELEASED UNDER THE OFFICIAL INFORMATION ACT 1982

2

Executive Summary

Flexible polyurethane foam (FPUF) is a common component in a wide range of furniture sold in New

Zealand. FPUF poses risks due to its high combustibility and ignitability.

To address risks from FPUF, on 17 July 2019 the Minister of Commerce and Consumer Affairs

released the Product Safety Policy Statement: Foam-filled furniture (the

Policy Statement). A Policy

Statement sets guidelines and expectations on safety benchmarks, enabling industry to self-adjust

and address safety issues with goods without formal regulatory intervention. Under section 30B of

the Fair Trading Act 1986, the Ministry of Business, Innovation and Employment (

MBIE) is required to

review the Policy Statement by 17 July 2024.

As part of the review, we investigated adherence to the Policy Statement, engaged with furniture

suppliers, the Environmental Protection Authority and Fire and Emergency New Zealand (

FENZ).

This report sets out our findings and recommendations from our review of the Policy Statement.

We found:

•

There has been limited change in the use of FPUF and very limited adoption of technologies to

increase fire resistance within the furniture industry.

•

Industry engagement with the Policy Statement has been limited and its guidance has largely

not been adhered to.

•

The number of avoidable residential fires remain largely similar.

•

There is insufficient evidence to determine the extent foam-filled furniture contributes to

avoidable residential fires and avoidable residential fire deaths in New Zealand.

Due to insufficient evidence to warrant revoking or amending the Policy Statement, we consider

there may be merit in continuing it until further evidence becomes available. A different response

could be considered if improvements can be made to the evidence base.

RELEASED UNDER THE OFFICIAL INFORMATION ACT 1982

3

Contents

Executive Summary ...................................................................................................................... 3

List of Acronyms ........................................................................................................................... 5

1

Introduction ......................................................................................................................... 6

Product Safety Policy Statement: Foam-Filled Furniture ................................................................ 6

2

Overview of the risks and the Policy Statement ..................................................................... 7

What is foam-filled furniture?......................................................................................................... 7

Risks of foam-filled furniture .......................................................................................................... 7

Evidence of contribution to fire deaths and injuries ....................................................................... 8

Existing regulations in New Zealand ............................................................................................... 9

Product safety policy statement: foam-filled furniture .................................................................. 9

3

The review ......................................................................................................................... 11

Context for the review .................................................................................................................. 11

Methodology ................................................................................................................................. 11

Limitations to the review .............................................................................................................. 11

4

How has the industry responded to the Policy Statement? .................................................. 13

Benchmarking ............................................................................................................................... 13

Manufacturers - use of standards ................................................................................................. 13

Informing consumers .................................................................................................................... 14

Impact of industry response ......................................................................................................... 14

5

Assessment of the effectiveness of the Policy Statement ..................................................... 15

There is limited data on recent residential structure fires in New Zealand ................................. 15

There has been no clear change in deaths from residential fires ................................................. 16

6

International regulatory developments ............................................................................... 17

7

Conclusion and recommendations....................................................................................... 20

Recommendations ........................................................................................................................ 20

RELEASED UNDER THE OFFICIAL INFORMATION ACT 1982

4

List of Acronyms

AS/NZS

Australia/New Zealand Standard

BS

British Standard

BS/EN

European standard adopted as a British standard

CO

Carbon Monoxide

CPSC

Consumer Product Safety Commission

DBT

UK Department of Business and Trade

FENZ

Fire and Emergency New Zealand

FFRs

Furniture and Furnishings (Fire)(Safety) Regulations 1988

FPUF

Flexible Polyurethane Foam

FTA

Fair Trading Act

HCN

Hydrogen Cyanide

HSNO

Hazardous Substances and New Organisms Act 1996

LOI

Limiting Oxygen Index

MBIE

Ministry of Business, Innovation and Employment

PolyBDE

Polybrominated Diphenyl Ether

PentaBDE

Pentabromodiphenyl Ether

POP

Persistent Organic Pollutants

S.I. No. 336

Statutory Instruments. No. 336

TB117-2013

California Technical Bulletin 117-2013

TBBPA

Tetrabromobisphenol A

TBDE

Tetrabromodiphenyl Ether

RELEASED UNDER THE OFFICIAL INFORMATION ACT 1982

TCEP

Tris (2-chloroethyl) Phosphate

TCPP

Tris(chloropropyl) Phosphate

5

1 Introduction

1.

The Fair Trading Act 1986 (

the FTA) provides options to address product safety issues. These

options include:

a.

product safety policy statements, which provide voluntary guidance and enable industry

to self-adjust by establishing an expected benchmark for types of goods

b.

unsafe goods notices, which prohibit the supply of types of goods and are issued where

it appears goods will or may cause injury

c.

product safety standards, which can set out design, testing and manufacturing

requirements for types of goods.

Product Safety Policy Statement: Foam-Filled Furniture

2.

In 2019 the Minister of Commerce and Consumer Affairs (the

Minister) released the

Product

Safety Policy Statement: Foam-filled furniture (the

Policy Statement) under section 30A the

FTA. The Policy Statement points to overseas fire-resistance rating benchmarks, and New

Zealand and overseas standards that set out performance and test criteria for ignitability to as

non-binding guidance for manufacturers and importers of foam-filled furniture products to

reduce the harm to people and property caused by fires involving foam-filled furniture.

3.

The Policy Statement also encourages retailers of FFF to inform consumers regarding the fire-

resistance and information regarding fire-safety of FFF being sold.

4.

Under section 30B of the FTA, MBIE is required to review the statement within five years of its

issue. This report summarises our review and is structured into five main sections:

a.

an overview of the risks posed by foam-filled furniture

b.

a summary of the Policy Statement

c.

a summary of developments since the Policy Statement was issued

d.

an assessment of the effectiveness of the Policy Statement

e.

conclusion and recommendations.

RELEASED UNDER THE OFFICIAL INFORMATION ACT 1982

6

2 Overview of the risks and the Policy Statement

What is foam-filled furniture?

5.

Foam-filled furniture is furniture containing flexible polyurethane foam (FPUF).

6.

FPUF is a synthetic polymer material used in a wide range of furniture sold in the New Zealand

market. FPUF provides support and cushioning, and can be found in lounge suites, couches,

seats and mattresses.

7.

FPUF is cost-effective to manufacture and can be cut, moulded or combined with other

materials. It first became commercially available in the 1950s and has been estimated to make

up between 40% and 70% of the New Zealand furniture market.1

Risks of foam-filled furniture

8.

FPUF is a combustible material which increases the potential danger of residential fires due to

how easily it ignites, the speed at which it burns, the heat released and the toxic chemicals

given off.

9.

The flammability of FPUF results from its chemical composition, porous structure and low

‘limiting oxygen index’ (LOI). Its porous, open-cell structure allows oxygen to diffuse within the

foam. LOI is the minimum concentration of oxygen that will support combustion of the

material. For FPUF, LOI is around 18 per cent, which is significantly below the atmospheric

concentration of oxygen (21 per cent).2

10.

As a result, FPUF furniture can be a significant source of combustible material that results in a

high heat output and rapid spread of fire. European testing in the early 1990s found that many

furniture items using FPUF produced over 1,000 kW of heat, and some over 2000 kW of heat,

sometimes within a few minutes of ignition. These peak heat release rates are sufficient to

cause a ‘flashover’ in some settings, where all combustible material in an enclosed room

ignites near-simultaneously.3

11.

During combustion, FPUF releases carbon monoxide (CO), hydrogen cyanide (HCN) and other

toxic gases.4 These exacerbate the risk posed by residential fires. CO and HCN are major

1New Zealand Institute of Economic Research. (2019).

Burning Couches: A cost-benefit analysis on regulating

for fire retardants in foam furniture. Page 41.

RELEASED UNDER THE OFFICIAL INFORMATION ACT 1982

2Yadav, A et al. (2022). Recent Advancements in Flame-Retardant Polyurethane Foams: A Review. I&EC

Research, 61, 15049.

3Björn Sundström, ‘Combustion behavior of upholstered furniture. Important findings, practical use, and

implications’,

Fire and Materials, 2021;45: 97–113.

4McKenna, S and Hull, T. (2016). The fire toxicity of polyurethane foams.

Fire Science Reviews, 5(3), 1.

7

asphyxiant gases present in fires that can lead to incapacitation. While CO is present in all fires,

HCN is generated in fires where FPUF is present.5

Evidence of contribution to fire deaths and injuries

12.

While there is a strong theoretical case for why foam-filled furniture is a significant fire hazard,

supported by some international evidence, there is very limited evidence of the role of foam-

filled furniture in recent residential fires in New Zealand and resulting deaths and injuries.

13.

In the UK, the prevalence of foam-filled furniture was identified as one of the main

contributors to an approximate doubling of fire deaths that occurred between the 1950s and

the 1980s.6 England’s fire statistics for 2010–2020 show that upholstered items (beds,

mattresses and furniture) were the material or item first ignited in 12% of domestic fire

incidents, but were responsible for 29% of fatalities. They were also identified as the main

material responsible for fire development in 16% of fires and 43% of fatalities. 7 In the US,

upholstered furniture was the first item ignited in 17.3% of residential fire deaths from 2018–

2020.8

14.

The last comprehensive analysis in New Zealand appears to have been a report produced by

Chelsia Wong at the University of Canterbury in 2001, which looked at fire incident statistics

from 1996–2000. Upholstered furniture and utensils (including chairs, sofas and beds) were

identified as the first ignited item in two fatalities (1.6%).9 This is far lower than recent

statistics from other countries. Upholstered furniture is likely to have been first ignited in some

fires where the material was unidentified.

15.

Upholstered furniture was confirmed to be ‘involved’ in 45 fatal fires (35.4%), which means

that it was one of the objects ignited and part of the fuel load, and was likely to have been

involved in a further 24 fatal fires (18.9%). This does not necessarily mean that it was a decisive

contributor to the fatalities, however.

16.

A 2018 review of fire deaths from 2007–2014 found that 50% of fatal fires began with ignition

of fabric, but it is unclear what proportion of these involved foam-filled furniture. There was

5 W. Woolley and A. Wadley, “Studies of the thermal decomposition of flexible polyurethane foams in air,

Fire

Res. Notes, vol. 951, pp. 1 – 17, 1972.

6 McKenna, S and Hull, T. (2016). The fire toxicity of polyurethane foams.

Fire Science Reviews, 5(3), 1.

7 Office for Product Safety & Standards (2023)

Fire Risks of Upholstered Products,

https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/642e8b80fbe620000c17ddb5/fire-risks-of-uphostered-

products-main-report.pdf.

RELEASED UNDER THE OFFICIAL INFORMATION ACT 1982

8 Consumer Product Safety Commission, 2018 – 2020 Residential Fire Loss Estimates,

https://www.cpsc.gov/s3fs-public/2018-to-2020-Residential-Fire-Loss-Estimates-Annual-Fire-Loss-Report-

Final.pdf.

8

also a large decrease in unintentional fire deaths generally, from 0.7 per 100,000 people in

1991-1997 to 0.28 deaths per 100,000 people in 2007–2014.10

Existing regulations in New Zealand

17.

Under the Consumer Guarantees Act 1993, goods supplied to a consumer must be of

acceptable quality. This includes a requirement that they must be safe.11 However, in the case

of goods that are unsafe, this is enforced solely by consumers exercising rights to refunds,

which would be unlikely to occur with a fire hazard.

18.

There are currently no regulations under the FTA for foam-filled furniture.

19.

There are three voluntary Australia/New Zealand standards which set out performance and

test criteria for ignitability:

a.

AS/NZS 3744.1:1998 Furniture – Assessment of the ignitability of upholstered furniture –

f Ignition source – Smouldering cigarette

b.

AS/NZS 3744.2:1998 Furniture – Assessment of the ignitability of upholstered furniture –

Ignition source – Match-flame equivalent

c.

AS/NZS 3744.3:1998 Furniture – Assessment of the ignitability of upholstered furniture –

Ignition sources – Nominal 160 mL/min gas flame and nominal 350 mL/min gas flame

20.

AS/NZS 3744.1 and AS/NZS 3744.2 are technically equivalent to and have been reproduced

from ISO 8191.1:1987 and ISO 8191.1:1988 respectively.

Product safety policy statement: foam-filled furniture

21.

The Policy Statement sought to address concerns about the combustibility and ignitability risks

of residential foam-filled furniture. It set expectations for manufacturers, importers and

retailers of foam-filled furniture that are summarised below.

RELEASED UNDER THE OFFICIAL INFORMATION ACT 1982

10 Rebbecca Lilley, Bronwen McNoe & Mavis Duncanson (2018),

Unintentional domestic fire-related fatal injury

in New Zealand: 2007-2014, 30 June 2018,

https://fireandemergency.nz/assets/Documents/Files/Report-167-

Unintentional-domestic-fire-related-injury-in-New-Zealand.pdf.

11 Consumer Guarantees Act, s7

9

SUMMARY OF THE POLICY STATEMENT

•

FPUF in furniture catches fire easily, burns and spreads fire quickly, and when on fire gives

off toxic gases more deadly than the fire itself.

•

Manufacturers should measure the fire resistance of foam-filled furniture by measuring the

time it takes for furniture to ignite; and/or the temperature at which furniture produces a

flashover.

•

Retailers should inform consumers on the safety and fire-risks of foam-filled furniture, for

example by displaying fire-resistance ratings on websites, signs and labels on the furniture.

•

Manufacturers and importers should consider ways to improve fire resistance, such as the

use of fire-resistant materials and improving the chemical composition of foam used in

furniture.

•

Manufacturers, importers, and retailers should consider the performance of their furniture

against specified ‘AS/NZS’ or ‘BS EN’ standards for fire-resistance, as well as the:

–

United Kingdom: Upholstered Furniture (Fire) (Safety) Regulations 1988

–

State of California: Technical Bulletin 116

–

Republic of Ireland: S.I. No. 336 – Industrial Research and Standards (Fire Safety)

(Domestic Furniture) order, 1988.

RELEASED UNDER THE OFFICIAL INFORMATION ACT 1982

10

3 The review

Context for the review

22.

Section 30B of the FTA requires MBIE to:

a.

review a product safety statement within 5 years after its issue (and if renewed, every 5

years thereafter)

b.

immediately following the review, prepare a report on the review for the Minister.

23.

The report must include recommendations to the Minister on whether a policy statement

should be continued, amended, revoked, or replaced.

Methodology

24.

In determining the effectiveness of the Policy Statement, we sought to answer:

a.

What options are there for reducing the risks presented by foam filled furniture?

b.

How has industry responded to the Policy Statement?

c.

Have there been any technological developments that could help mitigate the risk

caused by foam-filled furniture in the future?

d.

To what extent have these responses decreased risks posed by foam-filled furniture?

25.

As part of the review, we have:

a.

investigated adherence to the Policy Statement

b.

engaged with key industry stakeholders, including manufacturers and retailers, about

how they responded to the Policy Statement

c.

engaged with the Environmental Protection Authority and FENZ.

Limitations to the review

26.

We did not investigate consumer responses to the Policy Statement. The Policy Statement was

aimed at manufacturers, importers and retailers, and we have focused the review on their

response.

27.

Repeated attempts to contact a major manufacturer of FPUF and furniture containing FPUF

RELEASED UNDER THE OFFICIAL INFORMATION ACT 1982

was met with no response.

11

28.

We are also relying on existing data and research, and have not commissioned any new

research in carrying out this review. Existing research and data on causes of fires in

New Zealand is limited and much of it is out of date.

29.

Furthermore, it has been five years since the Policy Statement was published. Given the lags

present in a response to the policy statement (design and testing of new furniture, and

replacement of exiting furniture in homes), five years is a short time to expect to see a change

in avoidable residential fires and residential fire deaths.

RELEASED UNDER THE OFFICIAL INFORMATION ACT 1982

12

4

How has the industry responded to the Policy Statement?

30.

In late 2023, MBIE contacted retailers, distributors, and manufacturers of FPUF and furniture

containing FPUF to understand how they responded to the Policy Statement and whether

there were any corresponding impacts on their businesses.

Benchmarking

31.

The Policy Statement encourages industry to consult legislation from the UK, USA and the

Republic of Ireland as guidelines on how they can contribute to fire safety.

32.

One major retailer indicated they were aware of overseas legislation, including those in the

USA, UK and EU, they did not indicate they acted on this guidance in the Policy Statement.

33.

Other retailers, distributors, and manufacturers did not indicate they acted on this guidance.

Manufacturers - use of standards

34.

The Policy Statement sets out a list of standards to assist with the design, manufacture and

sourcing of safer foams and materials for FFF.

35.

One major New Zealand retailer of foam-filled furniture reported that wool has become a large

part of their business, and it has begun incorporating wool into their furniture and beds

containing FPUF. Wool has fire-retardant properties and is used to cover layers of FPUF,

making such furniture more fire-resistant than furniture stuffed solely with FPUF. FENZ

supports the use of cotton and wool.

36.

Cost was identified by a major retailer as a major barrier to using more fire-resistant materials

and potential change to furniture designs. Using alternatives to chemical flame retardants was

discussed as an option, however retailers reported trade-offs between providing furniture with

characteristics consumers want against manufacturing costs. This retailer also indicated that

they do cigarette and match testing, testing can be expensive and is typically driven by

commercial activities when requested.

37.

A foam distributor reported that while some customers specifically request fire retardant

foam, they don’t promote it as it costs considerably more than normal foam.

38.

One major retailer had not acted on the Policy Statement due to lack of awareness, but

indicated it was willing to look into steps to take on the guidance of the Policy Statement. It

indicated it would first speak with suppliers on how fire retardance could be achieved through

the composition of foam.

RELEASED UNDER THE OFFICIAL INFORMATION ACT 1982

13

Informing consumers

39.

The Policy Statement encourages retailers to inform consumers about the fire-resistance of

FFF.

40.

Although one major retailer of FFF advertises the fire-resistant property of wool they have

incorporated into their products, no other retailers we spoke to indicated they have taken

steps to inform consumers about the fire-resistance of FFF.

Impact of industry response

41.

Overall, industry engagement with the Policy Statement has been limited. Industry has

generally not followed guidance on the benchmark fire-resistance of FFF, the use of standards

set out in the Policy Statement, and informing consumers on fire-resistance of FFF.

RELEASED UNDER THE OFFICIAL INFORMATION ACT 1982

14

5 Assessment of the effectiveness of the Policy Statement

42.

There were two policy objectives of the Policy Statement: to minimise deaths, injuries and

damage to property, while also minimising the costs to industry, consumers and society as a

whole.

43.

Avoidable residential fire deaths have not reduced consistently since publication of the Policy

Statement.12 Although the number of residential fires has remained somewhat consistent since

the Policy Statement was published, FENZ stated that the severity of damage to property has

reduced over time.13

44.

Our overall assessment is that the Policy Statement is unlikely to have reduced deaths and

injuries from residential fires. The existing stock of foam-filled furniture is expected to be

replaced over the coming 10-20 years. However, the limited industry response to the Policy

Statement also suggests that the Policy Statement is not reducing risks posed by foam-filled

furniture.

There is limited data on recent residential structure fires in New Zealand

45.

Data on the number of residential structure fires is not regularly published in New Zealand.

There is no data on the role of foam-filled furniture in recent fires.

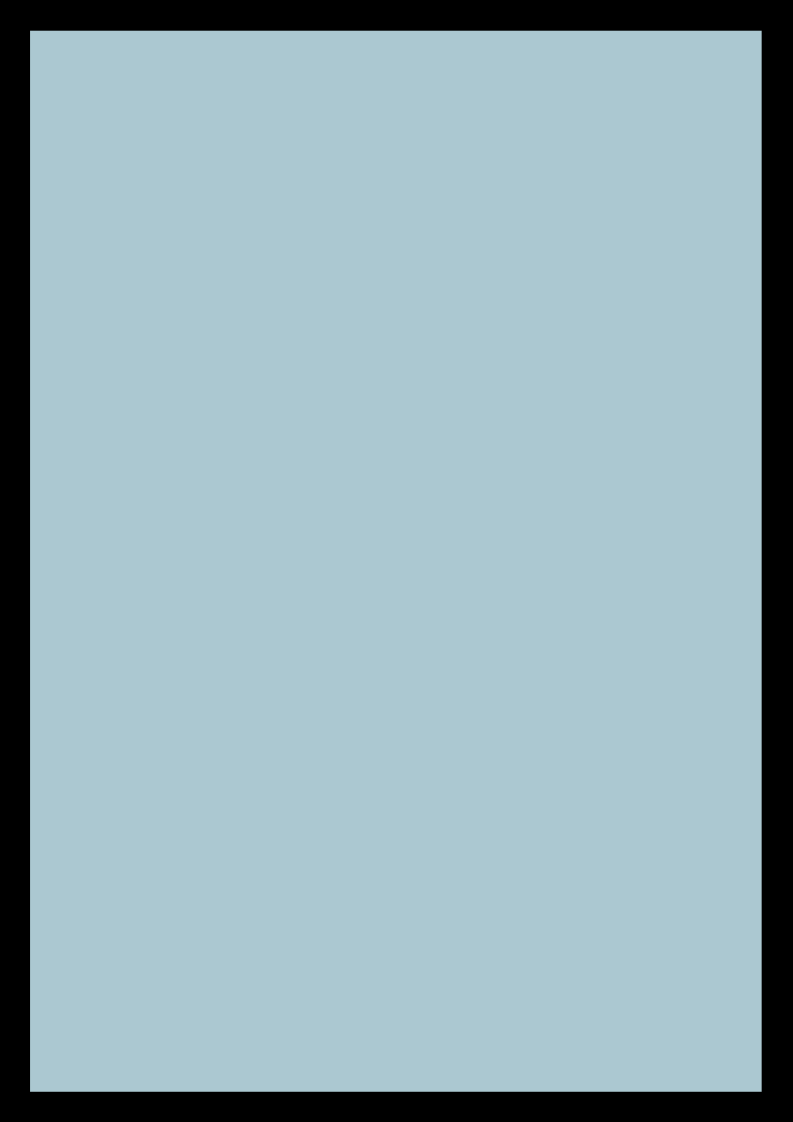

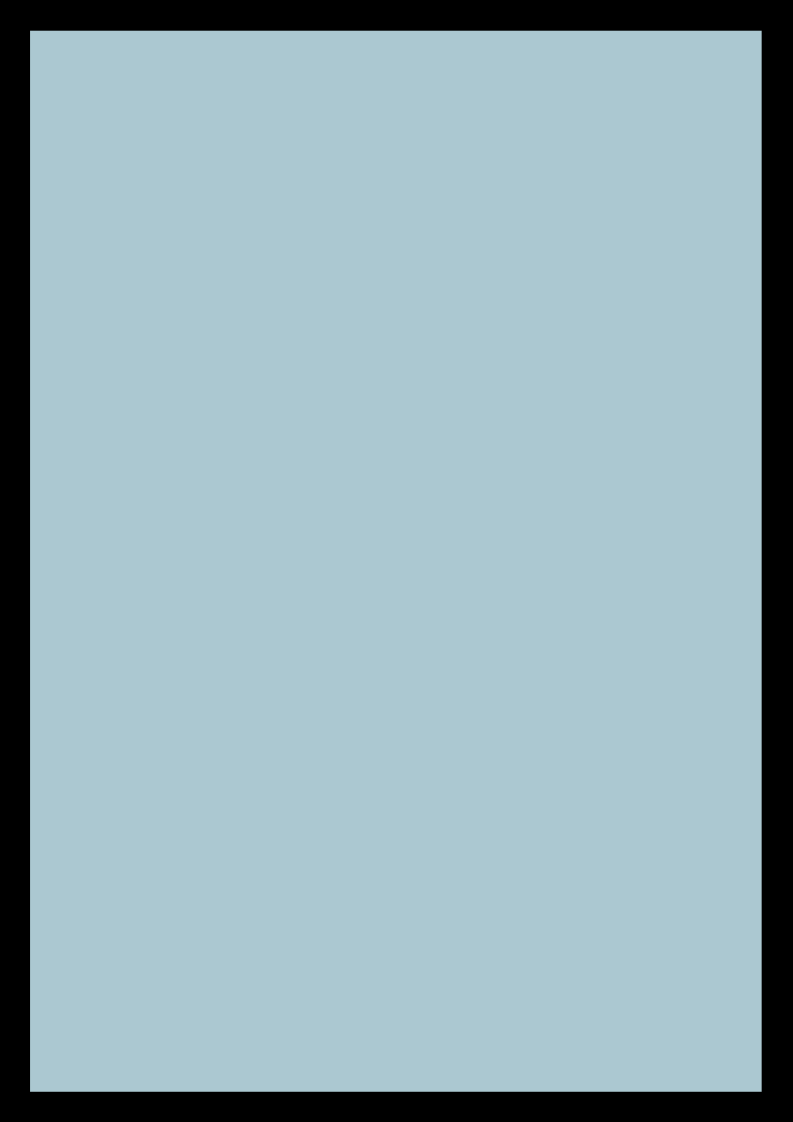

Figure 1 Residential structure fires attended

900

800

700

600

500

400

300

200

100

0

2018/2019

2019/2020

2020/2021

2021/2022

2022/2023

RELEASED UNDER THE OFFICIAL INFORMATION ACT 1982

12

Fire and Emergency New Zealand. (2023). Residential Structure Fires attended by TLA. OIA2023-00011372

Residential Structure Fire statistics NZ and Auckland (fireandemergency.nz) 13

Fire and Emergency New Zealand. (2023). Residential Structure Fires attended by TLA. OIA2023-00011372

Residential Structure Fire statistics NZ and Auckland (fireandemergency.nz); (23 November 2023). MBIE meeting

with Fire and Emergency New Zealand. Wellington

15

Source: Fire and Emergency New Zealand, Official Information Request 2023-0001137214

46.

The number of residential structure fires has remained somewhat consistent since the Policy

Statement was published, although there was a decline in the 2022/23 financial year.

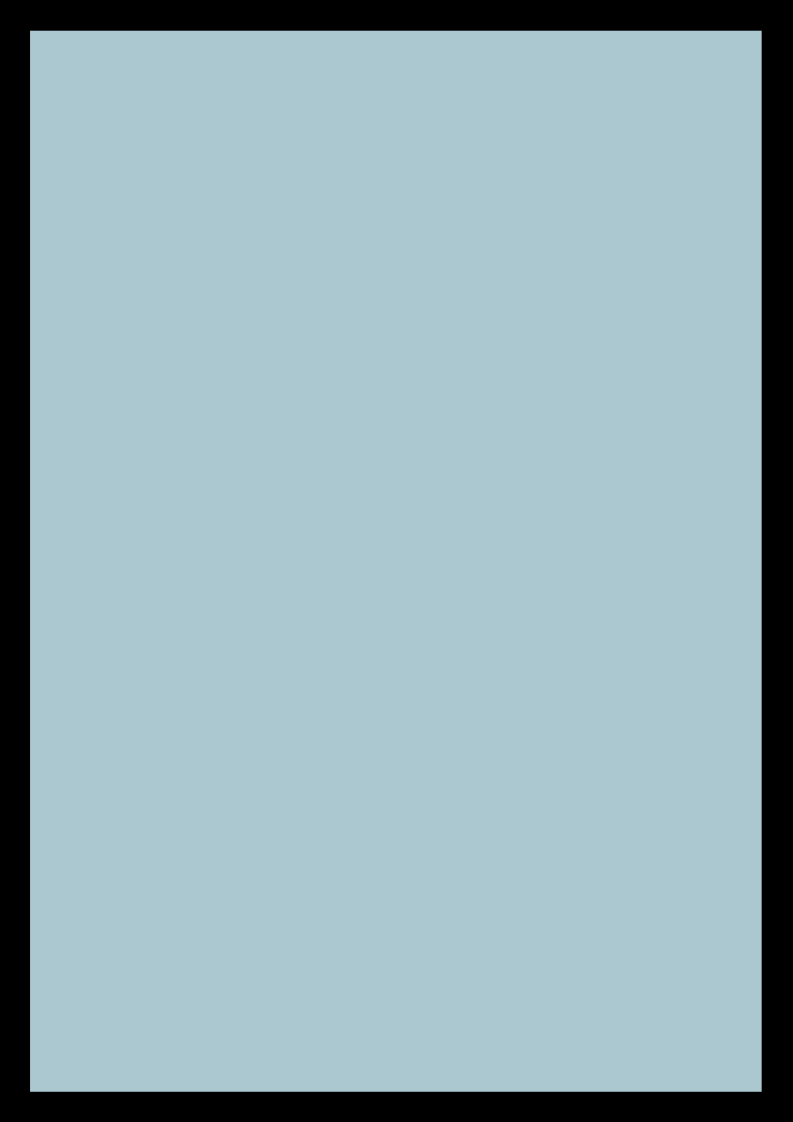

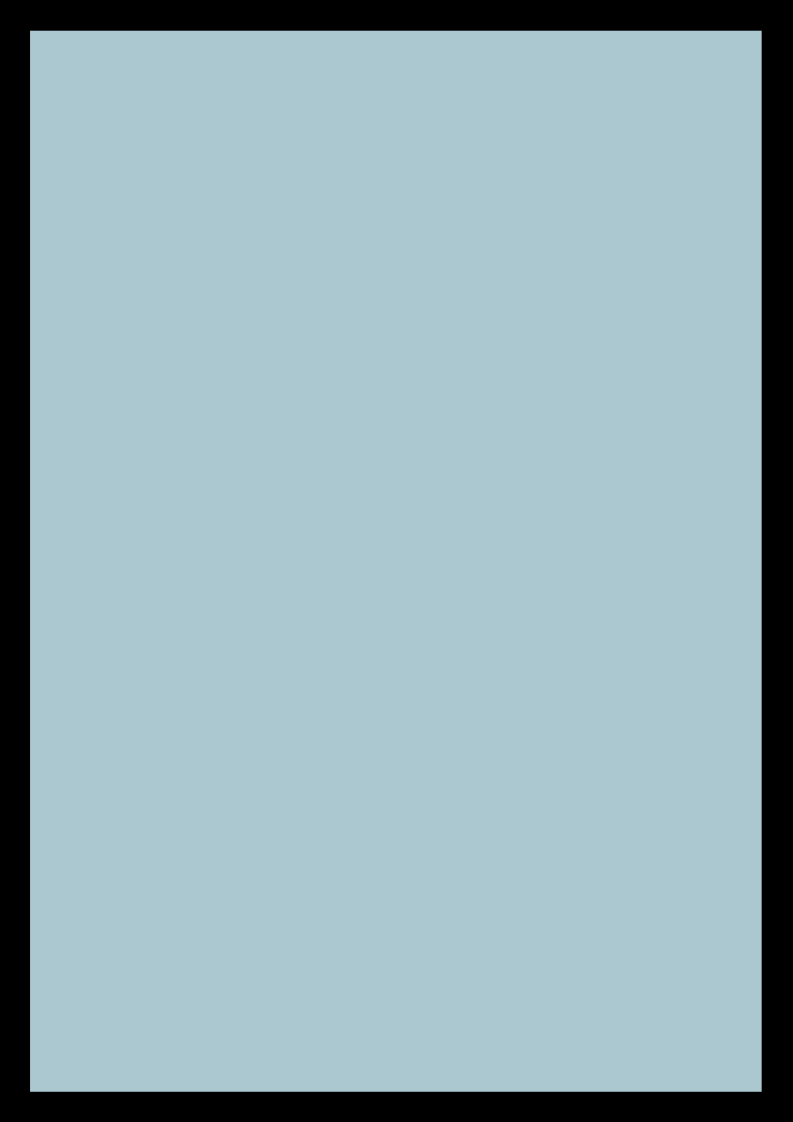

There has been no clear change in deaths from residential fires

Figure 2 Avoidable residential fire deaths by year

20

18

16

14

12

10

8

6

4

2

0

Source: Fire and Emergency New Zealand, Annual Reports 2011 - 2021

47.

The fire death rate has remained relatively consistent between 2011 and 2021. Similarly, as

discussed in section 2, there is no data on the extent to which foam-filled furniture contributed

to recent deaths.

RELEASED UNDER THE OFFICIAL INFORMATION ACT 1982

14

https://fireandemergency.nz/assets/Documents/Files/OIA-11372-Table-of-Residential-Structure-Fires-

Attended.pdf

16

6 International regulatory developments

48.

Since the Policy Statement was published in 2019, there have been a number of developments

in the regulation of foam-filled furniture in the United Kingdom and the United States of

America.

United Kingdom

49.

Flame retardants are applied extensively to textiles and furniture in UK, especially compared to

other countries.15

50.

The Furniture and Furnishings (Fire) (Safety) Regulations 1988 (the

FFRs) aim to protect

consumers from harm resulting from highly combustible domestic upholstered furniture. The

FFRs regulate the use of FPUF and require:

a.

filling materials to meet specified ignition requirements

b.

all upholstery to meet cigarette resistance requirements in accordance with BS 5852:

Part 1 and Schedule 4

c.

furniture covers to be match resistant

d.

permanent labelling on every new item of furniture (except mattresses and bed-bases)

e.

display labelling requirements where display labels are to be fitted to every new

furniture at the point of sale, except for specified items.16

51.

The UK has attributed the FFRs, more smoke alarms in homes, reduced cigarette consumption

and safer heating devices to a decrease in domestic house fires and deaths.17 A 2005 report

commissioned by the European Flame Retardants Association estimated the FFRs had

contributed to half of the reduction of fire deaths in the UK since the introduction of the

regulations.18 A 2009 report from Greenstreet estimated that the FFRs had led to 54 fewer

15 Page et al. (2023). A new consensus on reconciling fire safety with environmental & health impacts of

chemical flame retardants. 173. Environment International. 3.; Imperial College London. (2023). Experts

highlight environmental and health risks of current UK fire regulations. Experts highlight environmental and

health risks of current UK fire regulations | Imperial News | Imperial College London

16Furniture Industry Research Association. Fire safety of furniture and furnishings in the home – A guide to the

UK Regulations.

RELEASED UNDER THE OFFICIAL INFORMATION ACT 1982

17 (2023). Smarter Regulation: Consultation on the new approach to the fire safety of domestic upholstered

furniture. Department for Business and Trade (Office for Product Safety & Standards). Page 12. UK Department

for Business, Innovation and Skills, “A statistical report to investigate the effectiveness of the Furniture and

Furnishings (Fire) (Safety) Regulations 1988,” 2009.

17

deaths, 780 fewer non-fatal casualties, and 1,065 fewer fires on average each year between

2002 and 2007.19

52.

However, the FFRs also led to the widespread use of chemical flame retardants, and there are

now significant health and environmental concerns associated with chemical flame retardants.

53.

Accordingly, between 2 August and 24 October 2023, the UK Department for Business & Trade

(

DBT) publicly consulted on a new approach to the fire safety of domestic upholstered

furniture. The new approach consulted on a proposal to impose certain duties on

manufacturers, importers, selected suppliers, and re-upholsterers so that products20:

a.

do not contain any unsafe chemical flame retardants

b.

must not ignite on contact with an ignition source

c.

are slow-burning or self-extinguishing if ignited

d.

are tested and assessed consistently

e.

have a permanent safety label.21

54.

At the time of this review, results from the consultation have not been published and the UK

Government has not come to a policy position on the new approach.22

55.

DBT indicated that over 30% of residential fires involved an open flame to furniture, therefore

are now looking to keep the open-flame test rather than the smouldering test.

United States of America

56.

The California Technical Bulletin 117-2013 (TB117-2013) is a mandatory standard that

establishes flammability requirements for materials used to manufacture upholstered

furniture. In 2021, the United States’ Consumer Product Safety Commission (CPSC) introduced

a new mandatory federal flammability standard (16 CFR part 1640) requiring upholstered

furniture to:

a.

comply with the flammability requirements of TB117:2013 which includes the cover

fabric test, barrier materials test, and resilient filing material test, and

b.

include a permanent certification label with the ‘compliance statement’ which states

that the furniture complies with flammability requirements.23

19 Ibid.

20(2023). Smarter Regulation: Consultation on the new approach to the fire safety of domestic upholstered

RELEASED UNDER THE OFFICIAL INFORMATION ACT 1982

furniture. Department for Business and Trade (Office for Product Safety & Standards).

21 Ibid. pp.16, 35.

22 MBIE meeting with the Department of Business and Trade. Wellington.

23Standard for the Flammability of Upholstered Furniture (US), Part 1640. eCFR :: 16 CFR Part 1640 -- Standard

for the Flammability of Upholstered Furniture; United States Product Safety Commission. (2023). New Federal

18

57.

The federal standard covers fabrics, barrier materials, and resilient filling materials used in

upholstered furniture, with each being assessed separately. These materials are tested against

a ‘smouldering cigarette test’ as an ignition source.

58.

In January 2020, California enacted Assembly Bill No. 2998 (

AB 2998), banning the sale and

distribution of new upholstered furniture, replacement components for upholstered furniture,

foam in mattresses, and some children’s products for residential use if they contain more than

0.1% of specific flame-retardant chemicals, including antimony trioxide, chlorinated tris,

Tetrabromobisphenol A (TBBPA), and TCEP.24

59.

In California a flame-retardant chemical is banned if it is:

a.

a halogenated, organophosphorus, organonitrogen, or nanoscale chemical

b.

listed as a ‘designated chemical’ in the Health and Safety Code § 105440, or

c.

listed by Washington State as a Chemical of High Concern to Children.25

Safety Standard for Upholstered Furniture Fires Goes into Effect. New Federal Safety Standard for Upholstered

Furniture Fires Goes into Effect | CPSC.gov

RELEASED UNDER THE OFFICIAL INFORMATION ACT 1982

24 California State Government. (2023). Flame Retardants. Flame Retardants - Proposition 65 Warnings Website

(ca.gov); Assembly Bill. No. 2998, Chapter 924. Bill Text - AB-2998 Consumer products: flame retardant

materials. (ca.gov)

25 Bureau of Household Goods and Service, Department of Consumer Affairs. (2019) Assembly Bill 2998 (Bloom)

– Consumer Products: Flame Retardant Materials. Page 6.

19

7 Conclusion and recommendations

60.

We have insufficient information about the role of FPUF in recent fire deaths in New Zealand,

and we cannot draw definitive conclusions on whether the Policy Statement has led to

changes in the risks to consumers posed by FFF. However, the Policy Statement has certain

limitations:

a.

The Policy Statement is voluntary. This is a particular limitation where there is limited

appetite from industry to make changes to furniture designs. A common reason

provided by manufacturers and suppliers that didn’t follow the guidance in the Policy

Statement related to cost.

b.

We consider the Policy Statement’s recommendations for manufacturers and importers

are unclear. While the Policy Statement provides that manufacturers should measure

the fire resistance of foam-filled furniture, it does not provide a clear benchmark for

what fire resistance should be achieved. Businesses are ‘encouraged’ to adopt a

benchmark based on consulting various international fire safety standards, such as those

in the UK, California and Ireland.

61.

Furthermore, there has been little publicity or promotion of the Policy Statement. While the

Policy Statement indicates that MBIE had an intention to closely monitor its implementation

over the two years following publication, this did not happen. This was due to a combination

of a reorganisation of MBIE’s product safety functions in 2020, and the disruption of the

COVID-19 pandemic.

Recommendations

62.

The four options available to respond to this report are:

a.

Continue the Policy Statement in its current form with no change

b.

Amend the Policy Statement to make necessary refinements

c.

Revoke the Policy Statement altogether

d.

Replace the Policy Statement (e.g. with regulations under the Fair Trading Act).

63.

We have considered the extent to which each option will minimise risk of deaths, injuries and

damage to property, and minimise costs to industry, consumers and society as a whole.

RELEASED UNDER THE OFFICIAL INFORMATION ACT 1982

64.

To drive significant change to fire risks from FPUF would require a much more concerted

action than what has occurred to date under the Policy Statement. On the other hand, it is

difficult to recommend actions such as amending the Policy Statement or regulating, given the

20

limited evidence of a problem and the impact the Policy Statement has had on risks and harm

posed by FFF.

65.

There will be costs associated with continuing and amending the Policy Statement. This may

include some costs to the businesses that rely on the guidance in the Policy Statement to make

changes to their products and/or processes, and the requirement to review the Policy

Statement every five years.26

66.

There is insufficient information to say whether continuing the Policy Statement will minimise

risks and harm posed by FFF.

67.

However, the Policy Statement is currently the only guidance available to New Zealand

manufacturers, importers and retailers of FFF related to reducing the risk of harm to

consumers from fire when FFF is involved. Although revoking the Policy Statement may not

increase risk, risks of FFF-related harm will not be reduced.

68.

We therefore recommend the Policy Statement be continued.

RELEASED UNDER THE OFFICIAL INFORMATION ACT 1982

26 Section 30B(1)(a), Fair Trading Act 1986.

21

BRIEFING

Abuse in Care Royal Commission recommendations on the Accident

BRIEFING

Abuse in Care Royal Commission recommendations on the Accident

Compensation Scheme

Date:

18 September 2024

Priority:

Medium

Security

In Confidence

Tracking

BRIEFING-REQ-0002936

classification:

number:

Action sought

Action sought

Deadline

Hon Matt Doocey

s 9(2)(f)(iv)

24 September 2024

Minister for ACC

Contact for telephone discussion (if required)

Name

Position

Telephone

1st contact

Manager, Accident

Bridget Duley

04 897 6364

s 9(2)(a)

✓

Compensation Policy

Principal Advisor,

James Anderson

Accident Compensation

04 897 6792

–

Policy

The following departments/agencies have been consulted

Minister’s office to complete:

Approved

Declined

Noted

Needs change

Seen

Overtaken by Events

See Minister’s Notes

Withdrawn

Comments

RELEASED UNDER THE OFFICIAL INFORMATION ACT 1982

BRIEFING

Abuse in Care Royal Commission recommendations on the Accident

BRIEFING

Abuse in Care Royal Commission recommendations on the Accident

Compensation Scheme

Date:

18 September 2024

Priority:

Medium

Security

In Confidence

Tracking

BRIEFING-REQ-0002936

classification:

number:

Purpose

To provide you with advice on Abuse in Care Royal Commission of Inquiry (the Royal Commission)

recommendations on the Accident Compensation Scheme.

Executive summary

The Royal Commission has made recommendations to either:

• return the right to sue for personal injury compensation, for survivors of abuse in care, or

• expand Accident Compensation Scheme (AC Scheme) cover and entitlements for abuse in

care survivors, to compensate for all direct and indirect losses flowing from abuse and neglect

in care.

s 9(2)(f)(iv)

RELEASED UNDER THE OFFICIAL INFORMATION ACT 1982

0002936

In Confidence

1

Recommended action

The Ministry of Business, Innovation and Employment recommends that you:

a

Note that the Abuse in Care Royal Commission of Inquiry has recommended that the

Government either:

a. re-introduce the right to sue for personal injury compensation, for survivors of abuse in

care, or

b. expand Accident Compensation Scheme cover and entitlements for abuse in care

survivors, to compensate for all direct and indirect losses flowing from abuse and

neglect in care.

Noted

b

s 9(2)(f)(iv)

c

s 9(2)(f)(iv)

d

Note that work is progressing across Government to develop a separate redress scheme,

tailored to the needs of abuse in care survivors.

Noted

e

s 9(2)(f)(iv)

f

s 9(2)(f)(iv)

g

s 9(2)(f)(iv)

s 9(2)(a)

Bridget Duley

Hon Matt Doocey

Manager, Accident Compensation Policy

Minister for ACC

Labour, Science & Enterprise, MBIE

RELEASED UNDER THE OFFICIAL INFORMATION ACT 1982

18 / 09 / 2024

..... / ...... / ......

0002936

In Confidence

2

Background

The Royal Commission recommended amending the Accident Compensation

Scheme

1.

The Abuse in Care Royal Commission of Inquiry (the Royal Commission), has made

recommendations concerning the Accident Compensation Scheme (AC Scheme) in its final

report

Whanaketia: Through pain and trauma, from darkness to light (the Final Report) and

earlier interim report

He Purapura Ora, he Māra Tipu | From Redress to Puretumu

Torowhānui (the Redress Report, published in December 2021).

2.

The AC Scheme-specific proposals within these Royal Commission recommendations are:

a.

to create an exception to the ‘AC Scheme bar’ on compensatory damages for personal

injury, so that survivors of abuse in care can seek compensation through the courts, or

b.

if the Government does not introduce this exception, to reform the AC Scheme to

provide tailored compensation for survivors of abuse and neglect in care and other

appropriate remedies. As part of this reform:

i.

survivors should be fairly and meaningfully compensated for all direct and indirect

losses flowing from the abuse and neglect they experienced in care and that are

covered by the new puretumu torowhānui system and scheme, and

ii.

the application process should be survivor-focused, trauma-informed and

delivered in a culturally and linguistically appropriate manner.

3.

Annex One provides the original text of all the Royal Commission’s recommendations that

concern the AC Scheme. The Annex also identifies where there are portions of these

recommendations that are led within other portfolios. This includes recommendations

concerning the way that a separate redress scheme for survivors of abuse in care would

interact with, or take account of, survivors’ AC Scheme entitlements.

s 9(2)(f)(iv)

RELEASED UNDER THE OFFICIAL INFORMATION ACT 1982

0002936

In Confidence

3

s 9(2)(f)(iv)

s 9(2)(f)(iv)

RELEASED UNDER THE OFFICIAL INFORMATION ACT 1982

1 s 9(2)(f)(iv)

0002936

In Confidence

4

b.

s 9(2)(f)(iv)

RELEASED UNDER THE OFFICIAL INFORMATION ACT 1982

0002936

In Confidence

5

s 9(2)(f)(iv)

Annexes

Annex One: Abuse in Care Royal Commission of Inquiry recommendations related to the Accident

Compensation Scheme

s 9(2)(f)(iv)

RELEASED UNDER THE OFFICIAL INFORMATION ACT 1982

0002936

In Confidence

6

Annex One: Abuse in Care Royal Commission of Inquiry recommendations related to the Accident

Compensation Scheme

Recommendations

Lead portfolio Comment

Final Report Recommendation 11

If the government does not progress the Inquiry’s recommended civil litigation reforms (Holistic

Redress Recommendations 75 and 78 from the Inquiry’s interim report, He Purapura Ora, he Māra

Tipu: From Redress to Puretumu Torowhānui):

a. the government should reform the accident compensation (ACC) scheme to provide tailored

s 9(2)(f)(iv)

compensation for survivors of abuse and neglect in care and other appropriate remedies

ACC

b. survivors should be fairly and meaningfully compensated for all direct and indirect losses flowing

from the abuse and neglect they experienced in care and that are covered by the new puretumu

torowhānui system and scheme

c. the application process should be survivor-focused, trauma-informed and delivered in a culturally

and linguistically appropriate manner.

Redress Report Recommendation 18

The puretumu torowhānui [redress] scheme should:

› be open to al survivors, including those who have been through previous redress processes,

those covered by accident compensation, and those in prison or with a criminal record ….

Redress Report Recommendation 42

The [redress] scheme’s financial payments should not adversely affect survivors’ financial position

Lead

and should not count as income. Other than for ACC purposes, the financial payments should not

Coordination

reduce or limit any entitlements to financial support from the State, including welfare and

Minister for the

unemployment benefits, disability benefits and disability support services.

Government’s

These recommendations concern the

design, development, and responsibilities

Redress Report Recommendation 49

Response to the

of a separate redress scheme

Survivors should be able to make a claim to both the puretumu torowhānui [redress] scheme and

Abuse in Care

ACC. Any payments or services provided or facilitated by one should be taken into account by the

Royal

other.

Commission

Redress Report Recommendation 61

The puretumu torowhānui scheme should have the power to:

…

› provide information and recommendations to the Crown on areas of reform relevant to abuse in

care, including health, disability services, adoption, Oranga Tamariki, ACC, education and housing.

0002936

In Confidence

7

RELEASED UNDER THE OFFICIAL INFORMATION ACT 1982

Recommendations

Lead portfolio Comment

Redress Report Recommendation 75

The Crown should create in legislation:

s 9(2)(f)(iv)

› a right to be free from abuse in care

Justice

› a non

-delegable duty to ensure all reasonably practicable steps are taken to protect this right, and

direct liability for a failure to fulfil the duty

› an exception to the ACC bar for abuse in care cases so survivors can seek compensation through

s 9(2)(f)(iv)

ACC

the courts.

Redress Report Recommendation 76

The Crown should, if it decides not to enact the changes in recommendation 75, consider:

› empowering the puretumu scheme to award compensation

Replaced by Final Report Recommendation 11

› reforming ACC so that it covers the same abuse the new puretumu scheme covers and provides

fair compensation and other appropriate remedies for that abuse.

This recommendation is included in this

Redress Report Recommendation 78

table because it is referenced in Final

The Crown should amend the Limitation Act 1950 and Limitation Act 2010, with retrospective effect,

Report Recommendation 11

so:

Redress Report Recommendation 78

› any survivor who claims to have been abused or neglected in care while under 20 is not subject to

concerns limitation defences, which are

the Acts’ limitation provisions

available to defendants to prevent the

litigation of claims which, due to the time

› any survivor who has settled such a claim that was barred under either Act may relitigate if a court Justice

that has passed since the event in

considers it just and reasonable to do so

question, may raise natural justice issues

› any survivor who has had a judgment on such a claim can relitigate if they were found to have

for defendants

been barred under either Act’s limitation provisions, and the time bar prevented the survivor from

s 9(2)(f)(iv)

getting redress

› the court retains a discretion to decide that a case cannot go ahead if it considers a fair trial is not

possible.

0002936

In Confidence

8

RELEASED UNDER THE OFFICIAL INFORMATION ACT 1982