Status: Version 1.1

Activity: Scientific technical advice

Technical advice on: Macroalga

Asparagopsis taxiformis Lineage 2 detected in Iris

Shoal, Kawau Island, and Whangārei Harbour.

Date: 4 December 2024

Purpose of document

On 18 August 2024, Biosecurity Surveillance & Incursion Investigation requested a rapid risk

assessment of the macroalga

Asparagopsis taxiformis Lineage 2 to inform response decision making

and brief the Minister for Biosecurity. Given current efforts to manage exotic

Caulerpa in New

Zealand, a comparison of

A. taxiformis Lineage 2 with

Caulerpa was also requested to inform

potential management options.

Summary of advice

Asparagopsis taxiformis Lineage 2 (L2) was recently identified at two sites in Northland. Given the

distance between the two locations (~ 75 km), it cannot be assumed that this introduction is recent.

Asparagopsis taxiformis L2 is very similar in appearance to the widespread New Zealand native

Asparagopsis armata, and molecular techniques are often required to distinguish between the

species.

Asparagopsis is generally accepted to have multiple species (including

A. armata and

A. taxiformis),

but there is still uncertainty about how many distinct forms of

Asparagopsis there are. Each species

is currently divided into lineages based on genetic differences:

•

Asparagopsis armata lineages L1B and L2B, and

A. taxifomis L5 are native to New Zealand.

•

Asparagopsis armata L1A and

A. taxiformis L2 are native to Australia and the Indo-Pacific,

respectively; both have been introduced to the Mediterranean Sea where they are

considered invasive (have spread and negatively impacted local marine ecosystems).

Both

A. armata and

A. taxiformis demonstrate invasive behaviour in locations where

Asparagopsis is

not native, and their introduction has affected local biodiversity. It is less clear what the impacts will

be for introduction of a new lineage in areas where other

Asparagopsis species or lineages are native

(such as in New Zealand waters). The farming of

A.

armata is being trialled as a methane-reducing

livestock supplement. This could be impacted if

A. taxiformis L2 establishment alters the distribution

and abundance of

A. armata. However,

A. taxiformis L2 also has potential as a methane-reducing

livestock supplement, and an aquaculture nutritional supplement for finfish (including salmon).

Asparagopsis taxiformis L2 has the potential to establish throughout the coastline of the North Island.

The alga may establish in the South Island but is unlikely to reach high densities.

National or local eradication or suppression of L2 is not feasible with currently available methods

and technology.

Asparagopsis taxiformis L2 can reproduce sexually as well as via fragmentation,

making it very difficult to remove or treat effectively. Eradication and suppression of

Asparagopsis has never been attempted in other areas of the world, probably for similar reasons.

The main pathways for domestic spread are natural dispersal via currents and entanglement in

boating equipment. Using

pathway management options (such as Controlled Area Notices, rāhui,

awareness campaigns, etc.) to limit dispersal via boating equipment can slow spread over longer

distances. This over-arching approach reduces the long distance spread of marine pests in general

and is consistent with the fundamental biosecurity messaging of the exotic

Caulerpa response.

However, because we do not know the current distribution for

A. taxiformis in New Zealand waters

it would be difficult to effectively identify appropriate pathway management options without first

undertaking a

monitoring and surveillance programme to gather more information.

Rapid risk assessment Asparagopsis taxiformis Lineage 2 2024 V1.1

page: 2 of 16

Status: Version 1.1

Activity: Scientific technical advice

Supporting information

1. Taxonomy Asparagopsis taxiformis (Delile) Trevisan 1845

Kingdom: Plantae

Division: Rhodophyta

Class: Florideophyceae

Order: Bonnemaisoniales

Family: Bonnemaisoniaceae

Synonym:

Asparagopsis delilei,

Dasya delilei,

Asparagopsis sanfordiana,

Polysiphonia hilldenbrandii, Falkenbergia hillebrandii,

Polysiphonia patentifurcata.

Common name: red sea plume, limu kohu, supreme limu.

The taxonomy of

Asparagopsis is complicated and not finalised (Zanolla et al. 2022).

Asparagopsis

taxiformis is considered a species complex with six lineages (referred to as L1–L6 hereafter), which

look almost identical to each other but are genetically distinct (Zanolla et al. 2022). Taxonomic

diversity is likely a result of differences in distribution (Zanolla et al. 2022). There is debate as to

whether the lineages are genetic variants or independent isolated entities (Zanolla et al. 2022).

Whilst the lineages are genetically distinct, there is also genetic diversity within lineages based on

native and introduced ranges (Zanolla et al. 2022). For example, L2 in Japan is genetically distinct

from L2 in Hawaii (Zanolla et al. 2022).

2. Geographic distribution

Asparagopsis taxiformis is a widely distributed tropical and subtropical marine red alga (Fig. 1a, 1b).

The distribution of L2—the lineage detected in mainland New Zealand—encompasses the Indo-

Pacific region, including South Africa, Taiwan, Japan, and the Hawaiian Islands (Dijoux et al. 2014,

Zanolla et al. 2022).

Asparagopsis taxiformis L2 is also present in Lord Howe Island, Australia

(presumed a recent introduction; Andreakis

et al., 2016), and the western Mediterranean Sea (Fig.

5), where it is considered invasive (Zanolla et al. 2022; Navarro-Barranco et al. 2018). In New

Zealand, L5 is native and restricted to Rangitāhua/Kermadec Islands (Adams 1994, Nelson 2020).

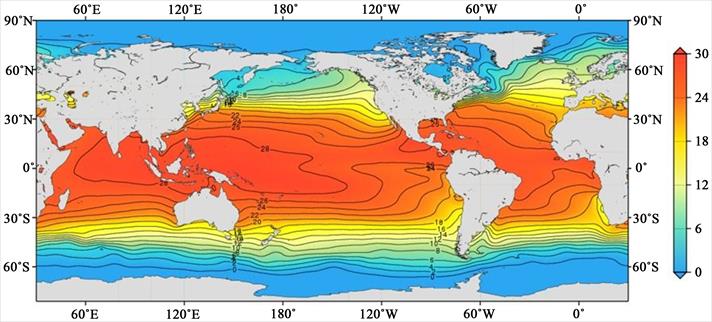

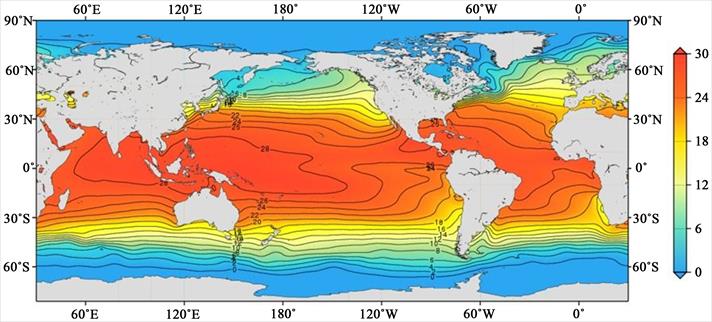

Figure 1a. Tropical and subtropical distribution of

Asparagopsis taxiformis based on 2716 georeferenced

records (observations, living specimens, occurrences). Accessed via Global Biodiversity Information Facility

(GBIF Secretariat 2023).

Rapid risk assessment Asparagopsis taxiformis Lineage 2 2024 V1.1

page: 3 of 16

Status: Version 1.1

Activity: Scientific technical advice

Figure 1b. Distribution of the annual sea surface temperature in °C (one-degree grid), World Ocean Atlas

climatology (decadal average 1955-2017; Reagan et al. 2024).

3. Biology and ecology

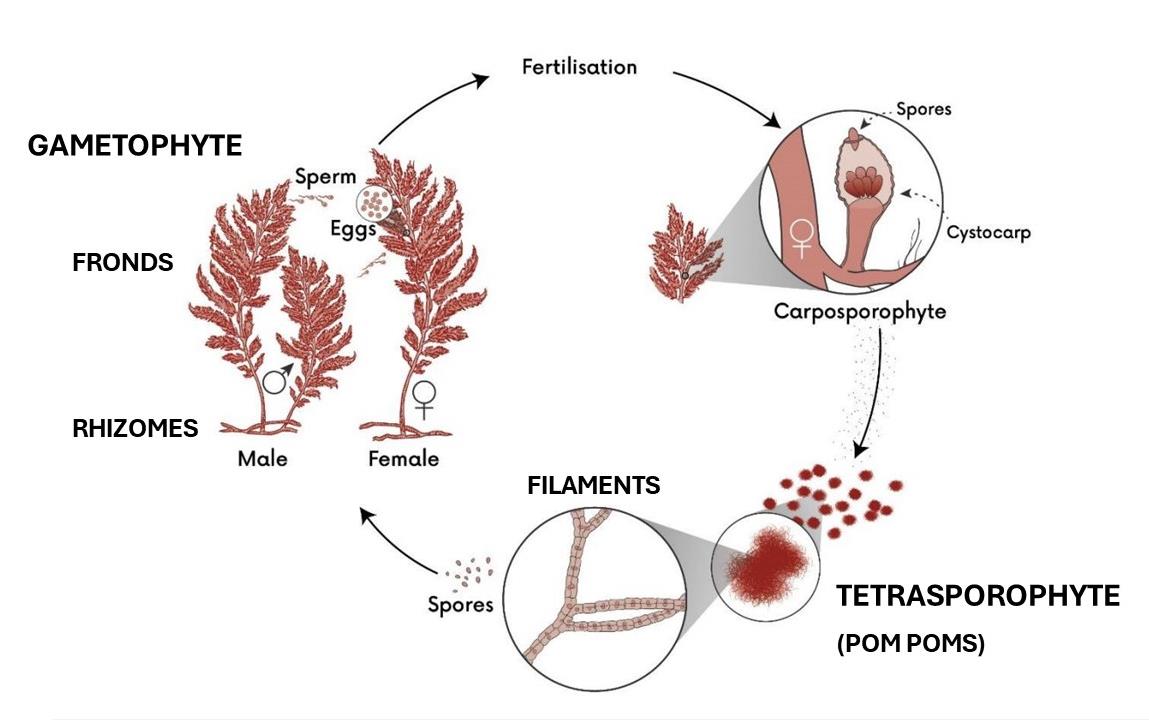

3.1 Morphology, reproduction and growth Asparagopsis taxiformis can reproduce sexually as well as vegetatively (via rhizomes and

fragmentation). The life cycle involves two macroscopic forms: a stalked, branching

gametophyte (fronds and rhizomes) and a filamentous, pompom-like tetrasporophyte

(filaments) (Fig. 2). The haploid gametophyte can reproduce asexually via frond fragments

regenerating into new individuals (Zanolla et al. 2022). The gametophyte can also reproduce

vegetatively via new shoots growing from rhizomes (Zanolla et al. 2022). The diploid

tetrasporophyte can reproduce vegetatively via pompom-like filaments separating from

original tissue (Zanolla et al. 2022). The presence of both macroscopic life stages is likely

nutrient and/or light dependant, indicated by the presence of gametophytes in the

Mediterranean Sea all year, and tetrasporophytes only in spring and summer (Zanolla et al.

2018). A similar pattern was observed in New Zealand, with an absence of tetrasporophytes

being sampled in winter, compared with multiple gametophyte samples (Biosecurity New

Zealand 2024a).

Rapid risk assessment Asparagopsis taxiformis Lineage 2 2024 V1.1

page: 4 of 16

Status: Version 1.1

Activity: Scientific technical advice

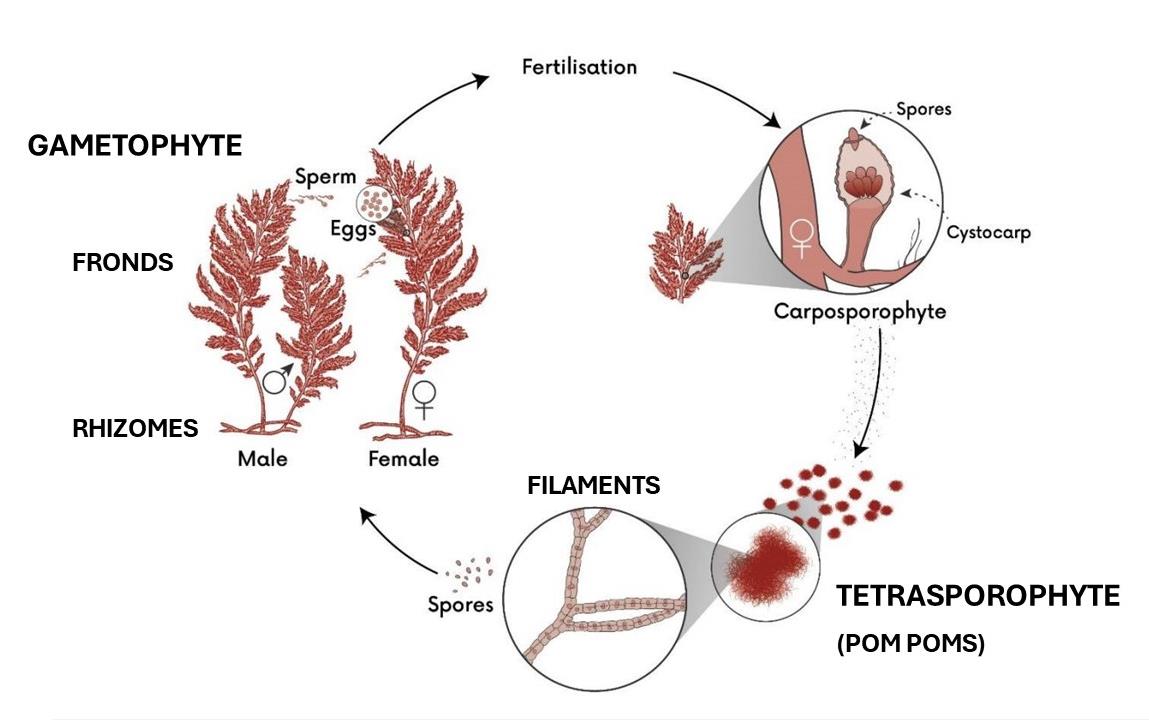

Figure 2. Life cycle of

Asparagopsis spp. showing the two morphologically distinct life stages, the

plant-like gametophyte and the pompom-like tetrasporophyte. Adapted from Wheeler et al. 2021.

3.2 Morphological differences between A. taxiformis L2 and Asparagopsis species native to

New Zealand

The capacity to rapidly differentiate between

L2 and native New Zealand

Asparagopsis is

crucial for considering whether eradication or suppression could be attempted. The

gametophytes of

A. taxiformis and

A. armata can be somewhat differentiated visually

(Appendix: Fig. S1). However, the other life stages cannot be distinguished without using

microscopy or molecular techniques. The tetrasporophytes of both

Asparagopsis species

also look very similar to other native red algae.

3.2.1 Native A. armata – Asparagopsis armata is considered a species complex, with the

genetically distinct L1B and L2B lineages present in New Zealand (Preuss et al. 2022).

Whilst the literature typically states

A. armata gametophytes feature characteristic

harpoon-like lateral branches, which

A. taxiformis lacks (Ní Chualáin et al. 2004, Zanolla

et al. 2019, Guiry 2024), this characteristic is not always well developed in New Zealand

lineages (D’Archino pers. comm.). Consequently, the harpoon-like lateral branches

should not be used as the sole distinguishable characteristic for New Zealand

A. armata lineages. Another distinguishable characteristic observed by Ní Chualáin et al. (2004)

was

A. armata gametophytes have ‘feathery branching’ compared to ‘closer spaced

laterals’ of

A. taxiformis. The tetrasporophytes of

A. armata and

A. taxiformis are

morphologically similar but not identical at a cellular level (Zanolla et al. 2019). See

Appendix Figure S1 for visual comparison of the two species.

3.2.2 Native A. taxiformis L5 – The six

A. taxiformis lineages are considered

morphologically cryptic but genetically distinct (Zanolla et al 2019). However, Zanolla et

al. (2019) identified ‘significant’ morphological differences between lineages which

could be helpful in microscopic examination. The authors found the width of the apical

cell, thickness of the cell wall, and width and length of the axial cell were diagnostic

Rapid risk assessment Asparagopsis taxiformis Lineage 2 2024 V1.1

page: 5 of 16

Status: Version 1.1

Activity: Scientific technical advice

characters to distinguish tetrasporophytes. However, the authors did not include

examination of L5, thus morphological examination of L5 tetrasporophytes would need

to be commissioned.

3.3 Habitat Asparagopsis taxiformis L2 commonly occurs in coastlines on rocky substrates or as

epiphytes (Zanolla et al. 2019). Introduced

L2 in the Mediterranean Sea has established in

temperate subtidal rocky shorelines (Fig. 5). In New Zealand,

L2 was observed at 11 m depth

growing on scallops, shell gravels and pebbles (Biosecurity New Zealand 2024a, NIWA 2024).

3.4 Invasiveness

Asparagopsis taxiformis L2 can form large, dense stands (Zanolla et al. 2017b), though not of

the scale seen in New Zealand of exotic

Caulerpa (Biosecurity New Zealand 2022). The L2

lineage exhibits morphological and physiological plasticity (e.g., photosynthesis occurs

within a wide temperature range), which is thought to support colonisation, establishment,

and fitness in introduced areas (Zanolla et al. 2014).

Asparagopsis taxiformis L2 introduction

can reduce the biomass of native macroalgal communities, as well as the abundance and

richness of invertebrates that live on macroalgal surfaces (Mancuso et al. 2021, Mancuso et

al. 2022, Mancuso et al. 2023; Navarro-Barranco et al. 2018; Zanolla et al. 2022).

3.5 Environmental tolerances

3.5.1 Temperature

Under laboratory conditions, the temperature tolerance of L2 ranges between 9 and 31

°C, growth occurs above 10 °C, and tetrasporophytes are produced between 21 and 27

°C (Ní Chualáin et al. 2004). In natural conditions, L2 occurs in areas of the

Mediterranean where mean annual sea surface temperatures are between ~ 16–22 °C

(Fig. 5; Pisano et al. 2020, GBIF Secretariat 2023).

3.5.2 Depth Asparagopsis taxiformis L2 can grow at depths between shallow subtidal up to 30 m

(Zanolla et al. 2014).

3.5.3 Latitude In Europe, L2 established at latitudes ranging from 28° to 44 °N, and in the Southern

Hemisphere at latitudes ranging from 21° to 34° S (NIWA 2024).

4. Introduction pathways

4.1 Long-distance translocation

The main pathway for long-distance translocation (100s – 1,000s of kilometres) of

A.

taxiformis is human-mediated marine transport by vessels via ballast water, hull fouling, and

entanglement of fragments in equipment (e.g., anchors, anchor chains). This is the most

likely introduction pathway for

L2 in New Zealand.

4.1.1 Introduction and spread of invasive

L2 in the Mediterranean Sea is linked to vessel

movements, and the opening of the Suez Canal (Mancuso et al. 2022, Zanolla et al.

2022).

4.1.2 Asparagopsis taxiformis L2 could have been introduced into New Zealand via the

ballast of vessels (e.g., cargo ships). Although there is no direct evidence of transport

Rapid risk assessment Asparagopsis taxiformis Lineage 2 2024 V1.1

page: 6 of 16

Status: Version 1.1

Activity: Scientific technical advice

along this pathway,

A. taxiformis tetrasporophytes can survive two weeks in darkness,

indicating the alga could survive in the ballast water of vessels (Zanolla et al. 2022).

4.1.3 Asparagopsis taxiformis L2 could have arrived in New Zealand as hull fouling, or as

fragments entangled in marine gear or equipment (e.g., anchor or anchor chain). This is

particularly likely given Whangārei Harbour and the Hauraki Gulf are popular yachting

destinations.

4.1.4 International aquarium trade is unlikely to be a pathway for long-distance

translocation of L2. No evidence was found of

A. taxiformis being traded as an aquarium

species nationally or internationally.

4.2 Short-distance translocation

The main pathway for short-distance translocation (10s – 100s of kilometres) of

A. taxiformis is likely via natural dispersal and human-mediated spread by entanglement in boating

equipment.

4.2.1 Asparagopsis species can spread naturally via fragmentation. Storms and wave

action break gametophyte fronds and tetrasporophyte filaments, which can drift to new

locations via currents and regenerate into new individuals.

4.2.2 Asparagopsis taxiformis L2 may also spread short distances attached to epifauna.

The alga was observed attached to an exotic pear crab (

Pyromaia tuberculata) in

Whangārei Harbour, suggesting crabs could be a potential pathway for local spread

(Biosecurity New Zealand 2024b).

4.2.3 Fragments of L2 gametophytes and tetrasporophytes can get entangled in boating

equipment (e.g., anchors, anchor chains), and hitchhike to new locations.

5. Potential distribution and spread

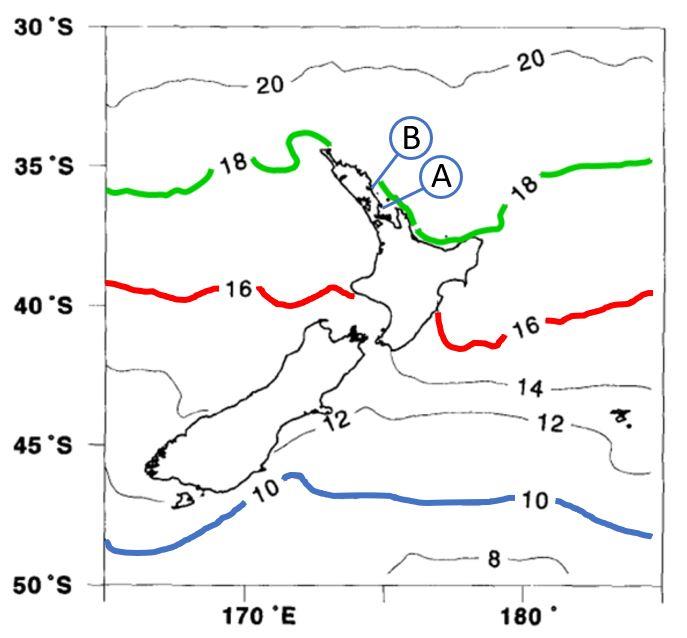

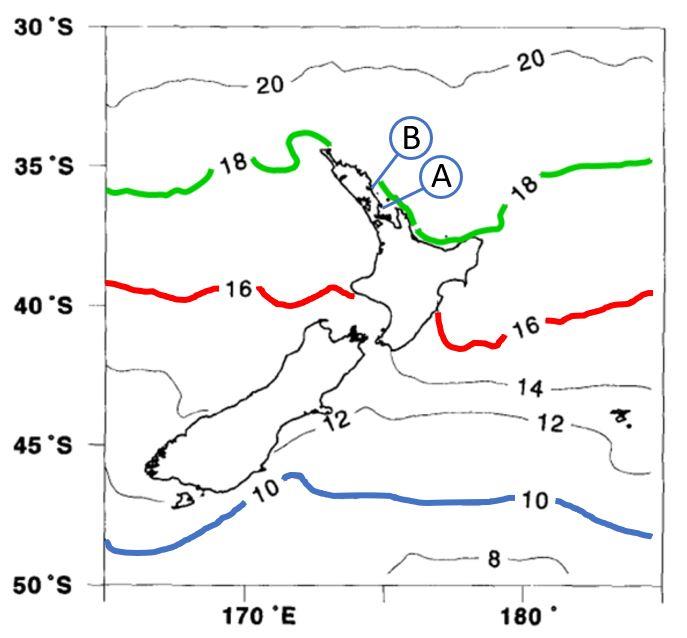

Asparagopsis taxiformis L2 is likely to spread in New Zealand temperate waters. The information

presented in section 3.5 suggests that the entirety of the North and South Island of New Zealand has

coastal water temperatures within the tolerance range of L2 (Fig. 3).

However, based on

A. taxiformis current distribution, L2 is unlikely to attain high density populations

in South Island waters (Fig. 4). Based on the evidence available (section 3.5.1), southern New

Zealand waters have temperatures that are suboptimal for

A. taxiformis, and could reduce L2

photosynthesis, growth, and tetrasporophyte production.

Rapid risk assessment Asparagopsis taxiformis Lineage 2 2024 V1.1

page: 7 of 16

Status: Version 1.1

Activity: Scientific technical advice

Figure 3. Locations where

Asparagopsis taxiformis L2 was found (A: Kawau Island B: Whangārei Harbour), and

New Zealand mean annual sea surface temperatures (from Chiswell, 1994).

Asparagopsis taxiformis L2 was

found between the 16 °C and 18 °C isotherms (respectively highlighted in red and green), but the literature

suggests that L2 could survive as far south as the 10 °C isotherm (highlighted in blue), encompassing all New

Zealand coastal waters.

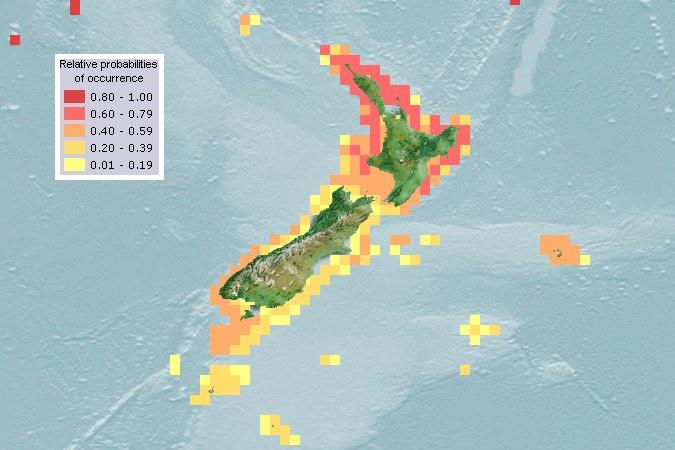

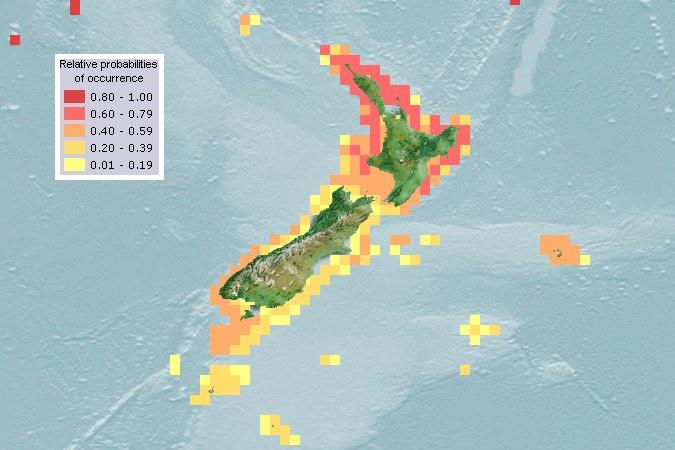

Figure 4. Computer-generated habitat suitability map for

Asparagopsis taxiformis, based on combined

occurrence data across all lineages (AquaMaps 2019). The entirety of the North and South Island has coastal

water temperatures within the tolerance range of

A. taxiformis Lineage 2, however temperatures in southern

New Zealand waters are likely to be suboptimal for growth and reproduction.

Rapid risk assessment Asparagopsis taxiformis Lineage 2 2024 V1.1

page: 8 of 16

Status: Version 1.1

Activity: Scientific technical advice

Figure 5. Mean sea surface temperatures (1982–2018) of the Mediterranean Sea and Northeastern Atlantic

box (modified from Pisano et al. 2020) and invasive

Asparagopsis taxiformis distribution. Black dots indicate

georeferenced records of

A. taxiformis (observations, living specimens, occurrences). Accessed via Global

Biodiversity Information Facility (GBIF Secretariat 2023).

6. Potential negative impacts

It is unlikely that L2 can impact New Zealand as much as exotic

Caulerpa. In well-studied regions like

the Mediterranean,

A. taxiformis has received less attention for its invasiveness compared to non-

native

Caulerpa species, despite being present for a longer time. In the Mediterranean,

A. taxiformis was found in the early 20th century off the coast of Sicily (Verlaque 1994), while the first invasive

Caulerpa (

C. taxifolia) was first detected in 1984 near Monaco (Meinesz et al. 1993).

Caulerpa has

been extensively researched due to its significant impacts abroad. The smaller volume of literature

on the introduction of

A. taxiformis and its L2 likely reflects its relatively limited impacts.

Asparagopsis taxiformis L2 impacts will be higher where L2 populations will achieve higher densities.

The density of L2 populations will be influenced by ecological factors such as environmental

conditions (like water temperatures) and interactions with other marine organisms (particularly

those with similar ecological niches, like other

Asparagopsis seaweeds).

Impacts in the North Island will likely be greater than the South Island due to higher ocean

temperatures that are more suitable to L2 (Fig. 3; Fig. 4). Similarly, within the North Island, impacts

in the upper north will likely be greater than the lower north for the same reason. Climate change

may also increase the magnitude of impacts, potentially promoting southward spread via increased

ocean temperatures. It is less clear how L2 could interact with the New Zealand native

Asparagopsis and to what extent L2 could have impacts. Most studies focused on

A. taxiformis impacts took place

in the Mediterranean, where no

Asparagopsis species is native.

6.1 Environmental

Asparagopsis taxiformis L2 has the potential to cause environmental impacts in New

Zealand, such as simplifying macroalgal habitat structure and reducing biodiversity of native

algal forests, particularly in the northernmost New Zealand waters.

Rapid risk assessment Asparagopsis taxiformis Lineage 2 2024 V1.1

page: 9 of 16

Status: Version 1.1

Activity: Scientific technical advice

6.1.1 In the Mediterranean Sea, L2 affects the abundance and species composition

of native macroalgae assemblages (Zanolla et al. 2018). For example, on the shores

of Favignana Island (Egadi Islands, Sicily, Italy), stands of L2 can have 90% less plant

biomass and 40% less invertebrate epibiont diversity than stands of native canopy-

forming macroalgae (Mancuso et al. 2022). However, such impacts and others

reported (Mancuso et al. 2021, Mancuso et al. 2023; Navarro-Barranco et al. 2018;

Zanolla et al. 2022) were recorded where mean annual sea temperatures are above

18 °C (Fig. 5, Pisano et al. 2020), and warmer than New Zealand coastal waters (Fig.

3).

6.1.2 In particular, L2 has the potential to replace widely distributed native

A. armata lineages. L2 outcompeted

A. armata in the Mediterranean (Zanolla et al.

2018), where mean annual sea temperatures are ~ 16–22 °C (Fig. 5, Pisano et al.

2020). There is also evidence of competition between

A. armata and

A taxiformis in

the Azores (NE Atlantic Ocean) (Martins et al. 2019), where mean annual sea

temperatures are ~ 18 °C (Fig. 1b, Reagan et al. 2024). Thus, the displacement of

A.

armata in New Zealand could occur at least above the 16 °C isotherm (Fig. 3), north

of Taranaki and Napier. However, there is conflicting evidence suggesting

A. armata has the capacity to displace

A. taxiformis (Martins et al. 2019, including references

therein). Given both species are difficult to differentiate, distribution data are

potentially unreliable (Andreakis et al. 2004).

6.1.3 Asparagopsis taxiformis L2 is unlikely to impact the New Zealand native L5.

This strain is restricted to the Rangitāhua/Kermadec Islands (Adams 1994, Nelson

2020), located about 1,000 km northeast of the North Island.

6.2 Economic

If L2 colonises large areas of seabed, this change in habitat structure could alter the

distribution and abundance of commercially valuable species, particularly native seaweeds.

For example, L2 could reduce the wild population of native

A. armata. Marine and on-land

farming of

A. armata received nearly $1.3 M from MPI between 2019 and 2023 to further

investigate its potential as a methane-reducing livestock supplement (Ministry for Primary

Industries 2024). Solely farming

A. armata on land could reduce the potential economic

impacts caused by L2 in the marine environment.

6.3 Socioeconomic

Large volumes of L2 beachcast, as has been observed in Whangārei Harbour (Allen pers.

comms, NIWA 2024), would impact aesthetic and amenity values, including tourism.

However, beachcast events of native and introduced seaweeds are commonplace in New

Zealand in the absence of L2. Restrictions put in place to stop the fragmentation and spread

of L2 may also negatively affect tourism (e.g., controls on swimming, boating, anchoring).

6.4 Cultural

The cultural impacts of L2 in New Zealand may be qualitatively similar to those caused by

exotic

Caulerpa (Biosecurity New Zealand 2021a), but likely at a much lesser scale:

“

The Caulerpa

incursion is associated with having a negative effect on the mauri (health and

spirit) of the ecosystem. Mauri and mana are inextricably tied, and where mauri is negatively

impacted, mana of tangata whenua is affected. Cultural values and concepts that relate to

the presence and impact of C. brachypus

include self-determination, environmental

stewardship and community wellbeing.” (Biosecurity New Zealand 2021a)

As with exotic

Caulerpa (Biosecurity New Zealand 2021b), impacts on mauri and mana could

include, but are not limited to:

Rapid risk assessment Asparagopsis taxiformis Lineage 2 2024 V1.1

page: 10 of 16

Status: Version 1.1

Activity: Scientific technical advice

▪ the depletion of native epifauna, including mollusc and crustacean species due

to habitat change;

▪ limitations in the customary and recreational gathering of molluscs and

crustaceans;

▪ limitations on cultural practices including manaakitanga;

▪ potential effects on whānau ora.

7. Potential positive impacts

No evidence could be found to suggest that L2 had positive environmental, socioeconomic, or

cultural impacts abroad. The literature analysed, including the

Asparagopsis review by Zanolla et al.

(2022), solely reports negative impacts. Potential negative environmental impacts associated with L2

introduction would likely outweigh any positive environmental impacts in New Zealand. However,

7.1 Economic

7.1.1 Asparagopsis taxiformis L2 may provide economic benefits in New Zealand as a

livestock supplement. As with

A. armata,

A. taxiformis has shown promise as a

potential livestock methane-reducing supplement. When added to cow and sheep

feed, both algae reduced ruminant methane production by up to 98% (Glasson et al.

2022). A review of

Asparagopsis use as a methane-reducing ruminant supplement

suggests research in this area often focuses on

A. taxiformis (Glasson et al. 2022),

providing a larger pool of information to draw from for potential trials in New

Zealand. In addition,

A. taxiformis may be a more reliable species for commercial-

scale production relative to

A. armata, particularly in marine-based farming. This is

because L2 has the capacity to tolerate wider environmental fluctuations compared

with

A. armata. The species may also produce more biomass when farmed relative

to

A. armata, as L2 doesn’t self-thin like

A. armata does (Zanolla et al. 2022).

7.1.2 Asparagopsis taxiformis L2 may provide economic benefits to New Zealand

finfish aquaculture, notably salmon farming. There is emerging research indicating

A. taxiformis has potential as an aquaculture nutritional supplement that enhances

farmed finfish growth, resilience, and immunity (Thépot et al. 2022, Pereira et al.

2024).

Asparagopsis taxiformis supplementation in Atlantic salmon (

Salmo salar)

farmed in Australia led to an increase of growth by 33% (Pereira et al. 2024).

8. Management options

The following assessment is not intended to replace analysis by Diagnostics, Readiness and

Surveillance. Comparisons between L2 and exotic

Caulerpa are made where appropriate.

There are six potential management options: national eradication, local eradication, suppression

(reduce the population), pathway management (slow the spread), gather additional surveillance

data, and no response.

8.1 Eradication

National or local

eradication of L2 is not feasible. This is largely due to the distribution of L2

incursion zones in New Zealand, biological and ecological characteristics, and diagnostic

challenges. Eradication attempts in areas where L2 is introduced have not been attempted.

8.1.1 The two primary incursion locations (Iris Shoal, Kawau Island, and Whangārei

Harbour) are roughly 75 km apart. Given L2 reproduces vegetatively as well as

sexually, it is possible the seaweed has a distribution wider than these two locations.

A distribution of that scale would be difficult to eradicate. As suggested in section

8.4, gathering additional surveillance data on the current distribution of L2 is

required to make an informed, practical management decision.

Rapid risk assessment Asparagopsis taxiformis Lineage 2 2024 V1.1

page: 11 of 16

Status: Version 1.1

Activity: Scientific technical advice

8.1.2 The red alga has the capacity to reproduce both asexually and sexually, as well

as vegetatively, suggesting only limited propagule pressure is required to establish a

population.

8.1.3 Potential distribution of L2 and the current distribution of native

A. armata lineages will likely overlap, limiting the use of some eradication methods, such as

dredging.

8.1.4 Identifying L2 in the field may be challenging, because the

A. taxiformis complex is considered morphologically cryptic.

Current methods to identify L2 in situ

would require microscopic examination. In addition, the capacity to rapidly

differentiate between L2 and

A. armata is crucial for eradication efforts. However,

this is difficult, as the tetrasporophyte of both species looks very similar.

8.2 Suppression

Suppression of L2 aimed at reducing the population via removal is not feasible due to the

same factors mentioned in section 6.1.1. As with eradication, suppression attempts in areas

where L2 is introduced have not been attempted.

8.2.3 Removal of biomass is required to reduce the current population. However,

unlike exotic

Caulerpa, L2 is difficult to differentiate from native seaweeds.

Consequently, attempts to remove L2 biomass may also reduce the biomass of

native seaweeds. Feasibility criteria for treatment would need to be carried out in

the absence of known treatment options, or previous suppression attempts abroad.

8.

3 Pathway management

Pathway management

could include Unwanted Organism status, Controlled Area Notices

and rāhui (prohibit human use), an awareness campaign, enhancing existing surveillance,

and combining current exotic

Caulerpa management initiatives with L2 management.

However, additional surveillance data is required to ascertain the current distribution of L2

in New Zealand.

8.3.1 Currently L2 has no regulatory status. Updating the status to an Unwanted

Organism under the Biosecurity Act 1993 would enable certain powers, which would

aid pathway management strategies but potentially limit the ability to utilise the

species in methane reduction initiatives. Unwanted Organism status would also be

challenging to enforce given diagnostic limitations with L2 and other red seaweeds

in New Zealand.

8.3.2 Controlled Area Notices (CAN) in conjunction with rāhui for the three incursion

locations would limit L2 spread via human activities. Controlled Area Notice zones

can place cleaning requirements on vessels and equipment within a defined area

when leaving a notice zone. This would prevent L2 attached to vessel anchors,

anchor chains, etc. being spread outside incursion zones. Notices would also place a

complete ban on the removal of any sea organisms from within a zone. Rāhui would

prohibit human use of incursion zones.

8.4 Gather additional surveillance data

To make an informed, practical management decision, gathering additional surveillance data

on the current distribution of L2 in the North Island would be helpful. As L2 is unlikely to

form high density populations around the South Island, collecting surveillance data around

the North Island would be sufficient. These data will give an indication of incursion scale and

inform feasibility criteria regarding management options. Such data could be collected by

Rapid risk assessment Asparagopsis taxiformis Lineage 2 2024 V1.1

page: 12 of 16

Status: Version 1.1

Activity: Scientific technical advice

existing marine surveillance programmes by NIWA, which currently conducts surveillance

along the east coast of the North Island twice yearly.

8.5 No response

This option recognises that eradication is not feasible, and that localised elimination and

suppression efforts will be expensive and are unlikely to succeed over the long term. This

option also recognises that the impacts of L2 are unlikely to be at the scale of exotic

Caulerpa in New Zealand. It is expected that L2 will spread mainly via entanglement with

recreational vessel anchors and anchor chains. In lieu of a response,

Caulerpa public

communications and the “Protect our Paradise” campaign could be leveraged to slow the

spread of L2, as the fundamental messaging—keeping vessel hulls, gear and anchors clean—

is applicable to a range of marine pests, including L2.

References:

Adams, N. M. (1994). Seaweeds of New Zealand. Canterbury University Press, Christchurch.

Andreakis, N., Procaccini, G., & Kooistra, W. H. (2004).

Asparagopsis taxiformis and

Asparagopsis armata

(Bonnemaisoniales, Rhodophyta): genetic and morphological identification of Mediterranean populations.

European journal of phycology, 39(3), 273-283. (link)

Andreakis, N., Costello, P., Zanolla, M., Saunders, G. W., and Mata, L. (2016). Endemic or introduced?

Phylogeography of

Asparagopsis (Florideophyceae) in Australia reveals multiple introductions and a new

mitochondrial lineage.

Journal of Phycology 52(1): 141–147.

AquaMaps (2019). Computer Generated Distribution Map for

Asparagopsis taxiformis. Retrieved from

https://www.aquamaps.org on 26/08/2024.

Biosecurity New Zealand (2021a). Rapid risk assessment

Caulerpa brachypus in Blind Bay, Great Barrier Island.

(link)

Biosecurity New Zealand (2021b). Memorandum to the CTO for UO status of

Caulerpa brachypus. (link)

Biosecurity New Zealand (2022). Memorandum to the Deputy Director-General, Biosecurity New Zealand.

Caulerpa Response Funding Option. (link)

Biosecurity New Zealand (2024a). Investigation Report INV GR361641. (link)

Biosecurity New Zealand (2024b). Interim post-sampling report Whangārei Habour NMHRSS Winter 2024.

Agreement Number C0031763 (formerly SOW23030) (Biosecurity New Zealand project MPI21506)

"National Marine High Risk Site Surveillance". (link)

Chiswell, S. M. (1994). Variability in sea surface temperature around New Zealand from AVHRR images.

New

Zealand Journal of Marine and Freshwater Research 28: 179–192.

Creese, R. G., Davis, A. R. and Glasby, T. M. (2004). Eradicating and preventing the spread of the invasive algae

Caulerpa taxifolia in NSW. Project No. 35593. NSW Fisheries Final Report Series. No. 64. NSW Fisheries,

Australia.

Dijoux, L., Viard, F., and Payri, C. (2014). The More We Search, the More We Find: Discovery of a New Lineage

and a New Species Complex in the Genus

Asparagopsis.

PLoS ONE 9(7): e103826.

doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0103826

GBIF Secretariat (2023).

Asparagopsis taxiformis (Delile) Trevis. GBIF Backbone Taxonomy. Checklist dataset.

(link) Accessed 21/08/24.

Glasson, C. R., Kinley, R. D., de Nys, R., King, N., Adams, S. L., Packer, M. A., Svenson, J., Eason, C. and

Magnusson, M. (2022). Benefits and risks of including the bromoform containing seaweed

Asparagopsis in

feed for the reduction of methane production from ruminants.

Algal Research 64: 102673.

Rapid risk assessment Asparagopsis taxiformis Lineage 2 2024 V1.1

page: 13 of 16

Status: Version 1.1

Activity: Scientific technical advice

Guiry, M. D. (2024). In Guiry, M. D. & Guiry, G. M. 01 February 2024. AlgaeBase. World-wide electronic

publication, National University of Ireland, Galway. (link). Accessed 04/09/2024.

Mancuso, F. P., Chemello, R., and Mannino, A. M. (2023). The effects of non-indigenous macrophytes on native

biodiversity: case studies from Sicily.

Journal of Marine Science and Engineering 11(7): 1389. (link)

Mancuso, F. P., D'Agostaro, R., Milazzo, M., and Chemello, R. (2021). The invasive

Asparagopsis taxiformis

hosts a low diverse and less trophic structured molluscan assemblage compared with the native

Ericaria

brachycarpa.

Marine Environmental Research,166: 105279. (link)

Mancuso, F. P., D'Agostaro, R., Milazzo, M., Badalamenti, F., Musco, L., Mikac, B., ... and Chemello, R. (2022).

The invasive seaweed

Asparagopsis taxiformis erodes the habitat structure and biodiversity of native algal

forests in the Mediterranean Sea.

Marine Environmental Research 173: 105515. (link)

Martins, G. M., Cacabelos, E., Faria, J., Álvaro, N., Prestes, A. C., Neto, A. I. (2019).

Patterns of distribution of

the invasive alga

Asparagopsis armata Harvey: a multi-scaled approach.

Aquatic Invasions 14: 582–593.

(link)

Meinesz, A., De Vaugelas, J., Hesse, B., & Mari, X. (1993). Spread of the introduced tropical green alga

Caulerpa

taxifolia in northern Mediterranean waters.

Journal of applied Phycology,

5, 141-147. (link)

Ministry for Primary Industries (2024). Sustainable Food and Fibre Futures projects. (link). Accessed

26/08/2024.

Navarro-Barranco, C., Florido, M., Ros, M., González-Romero, P., and Guerra-García, J. M. (2018).

Impoverished mobile epifaunal assemblages associated with the invasive macroalga

Asparagopsis

taxiformis in the Mediterranean Sea.

Marine Environmental Research 141: 44–52. (link)

Nelson, W. A. (2020). New Zealand seaweeds – an illustrated guide, ed. 2. Museum of New Zealand Te Papa

Tongarewa, Wellington, New Zealand.

Ní Chualáin, F., Maggs, C. A., Saunders, G. W., and Guiry, M. D. (2004). The invasive genus

Asparagopsis

(bonnemaisoniaceae, rhodophyta): molecular systematics, morphology, and ecophysiology of falkenbergia

isolates 1.

Journal of Phycology 40(6): 1112–1126.

NIWA (2024). Marine Exotic Species Note 138 August 2024. Notes on

Asparagopsis taxiformis

(Bonnemaisoniales, Rhodophyta) from Kawau Island and Whangārei Harbour. (link)

Pereira, A., Marmelo, I., Dias, M., Silva, A. C., Grade, A. C., Barata, M., Pousao-Ferreira, P., Anacleto, P.,

Maulvault, A. L. (2024).

Asparagopsis taxiformis as a Novel Antioxidant Ingredient for Climate-Smart

Aquaculture: Antioxidant, Metabolic and Digestive Modulation in Juvenile White Seabream (

Diplodus

sargus) Exposed to a Marine Heatwave.

Antioxidants 13(8): 949. (link)

Pisano, A., Marullo, S., Artale, V., Falcini, F., Yang, C., Leonelli, F. E., ... and Buongiorno Nardelli, B. (2020). New

evidence of Mediterranean climate change and variability from sea surface temperature

observations.

Remote Sensing 12(1): 132. https://www.mdpi.com/2072-4292/12/1/132

Preuss, M., Nelson, W. A., and D’Archino, R. (2022). Cryptic diversity and phylogeographic patterns in the

Asparagopsis armata species complex (Bonnemaisoniales, Rhodophyta) from New Zealand.

Phycologia 61(1): 89–96.

Reagan, J. R., Boyer, T. P., García, H. E., Locarnini, R. A., Baranova, O. K., Bouchard, C., Cross, S. L., Mishonov, A.

V., Paver, C. R., Seidov, D., Wang, Z., and Dukhovskoy, D. (2024). World Ocean Atlas 2023. NOAA National

Centers for Environmental Information. https://www.ncei.noaa.gov/products/world-ocean-atlas

Thépot, V., Campbell, A. H., Rimmer, M. A., Jelocnik, M., Johnston, C., Evans, B., and Paul, N. A. (2022). Dietary

inclusion of the red seaweed

Asparagopsis taxiformis boosts production, stimulates immune response and

modulates gut microbiota in Atlantic salmon,

Salmo salar.

Aquaculture 546: 737286. (link)

University of Maine (2023). Climate Reanalyzer. (link). Accessed 23/08/2024.

Verlaque, M. (1994). Checklist of introduced plants in the Mediterranean: origins and impact on the

environment and human activities.

Oceanologica acta. Paris,

17(1), 1-23.

Rapid risk assessment Asparagopsis taxiformis Lineage 2 2024 V1.1

page: 14 of 16

Status: Version 1.1

Activity: Scientific technical advice

Wheeler, T., Major, R., South, P., Ogilvie, S., Romanazzi, D., and Adams, S. (2021). Stocktake and

characterisation of New Zealand's seaweed sector: Species characteristics and Te Tiriti O Waitangi

considerations. Report for Sustainable Seas National Science Challenge project

Building a seaweed sector:

developing a seaweed sector framework for Aotearoa New Zealand. Sustainable Seas, Ko ngā moana

whakauka. 51 pp.

Zanolla, M., Altamirano, M., Carmona, R., De La Rosa, J., Sherwood, A., and Andreakis, N. (2014).

Photosynthetic plasticity of the genus

Asparagopsis (Bonnemaisoniales, Rhodophyta) in response to

temperature: implications for invasiveness.

Biological Invasions 17(5): 1341–1353. (link)

Zanolla, M., Carmona, R., and Altamirano, M. (2017a). Reproductive ecology of an invasive lineage 2

population of

Asparagopsis taxiformis (Bonnemaisoniales, Rhodophyta) in the Alboran Sea (western

Mediterranean Sea). Botanica marina, 60(6), 627-638. (link)

Zanolla, M., Altamirano, M., De la Rosa, J., Niell, F. X., and Carmona, R. (2017b). Size structure and dynamics of

an invasive population of lineage 2 of

Asparagopsis taxiformis (Florideophyceae) in the Alboran Sea.

Phycological Research, 66(1), 45-51. (link)

Zanolla, M., Altamirano, M., Carmona, R., De la Rosa, J., Souza-Egipsy, V., Sherwood, A., … Andreakis, N.

(2017c). Assessing global range expansion in a cryptic species complex: insights from the red seaweed

genus

Asparagopsis (Florideophyceae). Journal of Phycology, 54(1), 12–24. (link)

Zanolla, M., Carmona, R., De La Rosa, J. and Altamirano, M. (2018). Structure and temporal dynamics of a

seaweed assemblage dominated by the invasive lineage 2 of

Asparagopsis taxiformis (Bonnemaisoniaceae,

Rhodophyta) in the Alboran Sea.

Mediterranean Marine Science 19: 147-155. (link)

Zanolla, M., Carmona, R., De la Rosa, J., Salvador, N., Sherwood, A. R., Andreakis, N., and Altamirano, M.

(2019). Morphological differentiation of cryptic lineages within the invasive genus

Asparagopsis (Bonnemaisoniales, Rhodophyta).

Phycologia 53(3): 233–242. (link)

Zanolla, M., Carmona, R., Mata, L., De la Rosa, J., Sherwood, A., Barranco, C. N., Muñoz, A.R. and Altamirano,

M. (2022). Concise review of the genus

Asparagopsis Montagne, 1840.

Journal of Applied Phycology 34: 1–

17. (link)

Out of Scope

Rapid risk assessment Asparagopsis taxiformis Lineage 2 2024 V1.1

page: 15 of 16

Status: Version 1.1

Activity: Scientific technical advice

Appendix

Figure S1. Picture showing the fronds of Asparagopsis taxiformis (below) and Asparagopsis armata

(above). Arrows point to harpoon-like branches that can be found in

A. armata. While the gametophytes of

the two

Asparagopsis species can be visually distinguished, other life stages cannot be distinguished

without using microscopy or molecular techniques. The picture was taken in Granada, (Southern Spain) at

5-m depth.

(Credits: J. De la Rosa – from Zanolla, M., Carmona, R., Mata, L., De la Rosa, J., Sherwood, A., Barranco, C.

N., Muñoz, A.R. and Altamirano, M. (2022). Concise review of the genus

Asparagopsis Montagne, 1840.

Journal of Applied Phycology 34: 1–17. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10811-021-02665-z)

Rapid risk assessment Asparagopsis taxiformis Lineage 2 2024 V1.1

page: 16 of 16