link to page 2 link to page 2 link to page 39 link to page 39

OIA 20250193

Table of Contents

1.

Public Private Partnership Programme: The Public Sector Comparator and

1

Quantitative Assessment – A Guide for Public Sector Entities

2.

Public Private Partnership Programme: The New Zealand PPP Model and Policy:

38

Setting the Scene – A Guide for Public Sector Entities

OIA 20250193

Item 1

Page 1 of 67

Public Private Partnership Programme

The Public Sector Comparator and

Quantitative Assessment

A Guide for Public Sector Entities

September 2015

OIA 20250193

Item 1

Page 2 of 67

© Crown Copyright

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 New Zealand licence. In

essence, you are free to copy, distribute and adapt the work, as long as you attribute the work

to the Crown and abide by the other licence terms.

To view a copy of this licence, visit

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/nz/. Please note that no

departmental or governmental emblem, logo or Coat of Arms may be used in any way which infringes any

provision of the

Flags, Emblems, and Names Protection Act 1981. Attribution to the Crown should be in written

form and not by reproduction of any such emblem, logo or Coat of Arms.

ISBN: 978-0-478-43684-6 (Online)

The Treasury URL at September 2015 for this document is

http://www.treasury.govt.nz/statesector/ppp/guidance/public-sector-comparator

The PURL for this document is

http://purl.oclc.org/nzt/g-ppp-pscqa

link to page 31 link to page 30 link to page 30 link to page 30 link to page 29 link to page 28 link to page 28 link to page 26 link to page 25 link to page 24 link to page 20 link to page 19 link to page 18 link to page 18 link to page 16 link to page 16 link to page 14 link to page 13 link to page 13 link to page 11 link to page 11 link to page 11 link to page 10 link to page 10 link to page 8 link to page 7 link to page 7 link to page 6

OIA 20250193

Item 1

Page 3 of 67

Contents

1 About this Guidance ......................................................................................... 1

2 Introduction ....................................................................................................... 2

Core Definitions .................................................................................................. 2

Link with Better Business Case Guidelines ......................................................... 3

Part 1: The PSC and its Application ......................................................................

5

3 Overview of the Public Sector Comparator .................................................... 5

The Reference Project ........................................................................................ 6

Transferred Risk ................................................................................................. 6

Tax Adjustment ................................................................................................... 6

Presentation of the PSC ...................................................................................... 6

4 Quantitative Assessment ................................................................................. 8

Procuring Entity’s Internal Costs ......................................................................... 8

Assessment Framework ...................................................................................... 9

Setting the Affordability Threshold .................................................................... 11

Financial Close ................................................................................................. 11

Part 2: Detailed Guidance .....................................................................................

13

5 Risk Quantification ......................................................................................... 13

Types of Risk .................................................................................................... 13

Identifying Risks ................................................................................................ 14

Quantifying Risks .............................................................................................. 15

6 Proxy Bid Model .............................................................................................. 19

Methodology ..................................................................................................... 20

Financing Assumptions ..................................................................................... 21

Taxation Calculations ........................................................................................ 23

GST................................................................................................................... 23

Unitary Charge Profile ....................................................................................... 24

7 Tax Adjustment ............................................................................................... 25

Impact of Taxation ............................................................................................ 25

Rationale for Adjustment ................................................................................... 25

Adjustment Process .......................................................................................... 26

The Public Sector Comparator and Quantitative Assessment | i

link to page 37 link to page 36 link to page 35 link to page 34 link to page 32 link to page 32

OIA 20250193

Item 1

Page 4 of 67

8 Discount Rates ................................................................................................ 27

The Discount Rate Model .................................................................................. 27

Specification of the Discount Rate .................................................................... 29

Inputs ................................................................................................................ 30

Updates ............................................................................................................. 31

Appendix A: Risk Al ocation Example ................................................................ 32

The Public Sector Comparator and Quantitative Assessment | ii

link to page 6 link to page 6

OIA 20250193

Item 1

Page 5 of 67

1 About this Guidance

How to use this guidance

1.1 This guidance has been written by the Treasury PPP Team. It must be read in conjunction

with other Public Private Partnership (PPP) guidance and applied in consultation with the

Treasury PPP Team. It assumes that the Treasury’s Standard Form PPP Project Agreement

wil form the basis of the contract to be signed with the private sector partner

.1

1.2 This document should be read by public sector entities (referred to as procuring entities

throughout this guidance document) that are considering or implementing PPP as a

procurement option for a major infrastructure project; specifically, those staff involved in the

development and internal approval of the project business case and procurement process.

1.3 A glossary of terms used throughout this document is available on the Treasury websi

te.2

The New Zealand PPP model

1.4 In the New Zealand context, a PPP is a long-term contract for the delivery of a service,

where provision of the service requires the construction of a new asset, or enhancement of

an existing asset, that is financed from external (private) sources on a non-recourse basis,

and full legal ownership of the asset is retained by the Crown.

1.5 PPP procurement has been implemented in New Zealand for the primary purpose of

improving the focus on, and delivery of, required service outcomes from major infrastructure

assets. Whole of life services are purchased under a single long-term contract with

payments to the contractor based on availability and performance of the asset. The

combination of assets and services required to be delivered by the private sector are referred

to in this document as the ‘project’.

1.6 The PPP model seeks to improve outcomes by capturing best practice and innovation from

the private sector. Lessons learnt from PPP projects can be implemented across a broader

portfolio of public assets to significantly leverage the benefits of single PPP transactions.

The competitive procurement process, focus on outcomes (with minimal input specifications

and constraints), appropriate risk al ocation and performance based payment mechanisms

that put private sector capital at risk optimise the incentives and flexibility for private sector

participants to deliver innovative and effective solutions.

1.7 PPP procurement is only used where it offers value for money over the life of the project,

relative to conventional procurement methods. This means achieving better outcomes from

a project than if it were procured using conventional methods, for the same, or lower, net

present cost.

Questions and further information

1.8 General enquiries about the information contained in this guidance can be sent to

[email address]. Other guidance documents and useful information can be found at

www.treasury.govt.nz/statesector/ppp.

1

http://www.treasury.govt.nz/statesector/ppp/standard-form-ppp-project-agreement

2

http://www.treasury.govt.nz/statesector/ppp/guidance/glossary

The Public Sector Comparator and Quantitative Assessment | 1

OIA 20250193

Item 1

Page 6 of 67

2 Introduction

2.1 This document provides guidance on developing the Public Sector Comparator (PSC) and

undertaking quantitative value for money assessment for a PPP project. It is structured in

two parts:

•

Part one contains an explanation of the PSC and guidance for how to assess the value

for money of delivering a project as a PPP compared with conventional public sector

delivery.

•

Part two contains more detailed guidance for agencies and their advisors, including how

to develop the PSC and Proxy Bid Model.

2.2 This guidance document is intended to provide an overview of the PSC development

process. It is expected that procuring agencies wil recruit specialist staff and advisors, and

engage with the Treasury PPP Team, when applying the guidance.

Core Definitions

2.3 There are three core terms used in this guidance: the Public Sector Comparator (PSC), the

affordability threshold and the Proxy Bid Model (PBM).

Public Sector Comparator

2.4 The PSC is an estimate of the risk adjusted whole of life cost of a project if it were to be

delivered by the procuring entity using conventional procurement methods. It is primarily

used as a benchmark against which to assess the net present cost of procuring the project

as a PPP. The PSC is comprised of the capital, operating and risk management costs of the

procuring entity’s reference project and a tax adjustment to enable fair comparison with

private sector PPP proposals.

2.5 The PSC should be a realistic estimate of the costs incurred by the procuring entity if it were

to deliver the project using conventional public sector delivery methods. These costs should

enable the procuring entity to deliver the same scope and quality of service outcomes that

are required of the contractor under the PPP contract over the same time period. It should

take account of the risk allocation between the procuring entity and the private sector

consortium contracted to deliver the project as reflected in the commercial principles

developed for the project and included in the PPP contract.

2.6 It is important to note that the PSC may not represent the ful costs of the project because it

is intended to match the scope of the proposed PPP contract. For example, the PSC for a

PPP to design, build, finance and maintain a set of schools would not include salary costs for

teachers because the PPP contractor is not responsible for teaching services. Procuring

agencies should develop whole of life cost estimates for retained costs to inform investment

decisions and budgeting. However, for the purposes of this guidance the term PSC refers

only to the costs for those services that are within the scope of the proposed PPP contract,

unless otherwise specified.

The Public Sector Comparator and Quantitative Assessment | 2

link to page 8 link to page 8

OIA 20250193

Item 1

Page 7 of 67

Reference Project

2.7 The reference project is the whole of life asset and service delivery solution that would be

procured using conventional methods if the project was not procured as a PPP. It is

primarily used as an input to the PSC and PBM. The reference project should be designed

and its costs estimated such that it is capable of achieving the same outcomes and

performance requirements that are expected of the private sector under the PPP contract.

Affordability Threshold

2.8 The affordability threshold is disclosed to parties participating in a procurement process for a

PPP project (the respondents) as the maximum ‘price’ that the procuring entity is prepared to

pay a contractor for delivery of the project. It is expressed as a single point estimate net

present cost. Any proposal with a net present cost in excess of the affordability threshold wil

be considered non-compliant.

2.9 The affordability threshold should be equal to the PSC less any additional costs that the

procuring entity wil incur over the life of the contract as a result of procuring the project as a

PPP. This may include additional transaction and contract management costs over and

above the costs borne through conventional procurement. Accordingly, the net present cost

of the PPP project wil be no more than the cost of the project if it were procured using

conventional procurement methods.

Proxy Bid Model

2.10 The Proxy Bid Model (PBM) calculates the estimated periodic service charge (the unitary

charge) that a contractor would require to finance and deliver the project to the level of

performance specified in the PPP contract. The procuring entity does not begin paying the

unitary charge until the asset is operational and the contractor is delivering the required

services.

2.11 The PBM is comprised of the risk adjusted reference project costs with additional private

sector financing, tax and PPP specific cost assumptions. It uses the same underlying

capital, operating, risk management and tax assumptions as the PSC.

Link with Better Business Cases Guidelines

2.12 The PSC is an important analytical tool for considering the appropriateness of procuring a

project as a PPP. It is important for agencies to consider this guidance document carefully

during the development of a business case where PPP procurement is one of the

procurement options being considered.

2.13 Depending on the type of project being considered it may be appropriate to develop an initial

PSC as part of the Indicative Business Case. However, in most instances, the PSC should

be fully developed as part of the development of the Detailed Business Case. Procuring

entities should contact the Treasury PPP Team for specific advice for their project.

2.14 Guidance on applying the Better Business Cases framework is available on the Treasury

website.

3 Specific guidance on how to consider PPP procurement in the context of the

Better Business Cases framework is included in other Treasury PPP guidanc

e.4

3

http://www.treasury.govt.nz/statesector/investmentmanagement/plan/bbc

4

http://www.treasury.govt.nz/statesector/ppp/guidance/model-and-policy

The Public Sector Comparator and Quantitative Assessment | 3

OIA 20250193

Item 1

Page 8 of 67

Part One:

The PSC and its Application

The Public Sector Comparator and Quantitative Assessment | 4

link to page 10

OIA 20250193

Item 1

Page 9 of 67

3 Overview of the Public Sector Comparator

Introduction

3.1 The PSC is based on the procuring entity delivering the same scope of service and accepting

the same risks as those allocated to the private sector under the PPP contract. The PSC

comprises the capital and operating costs for a reference project, transferred risk and a tax

adjustment.

Figure 1 il ustrates how the series of cash flows for the PSC are presented as a

net present cost.

3.2 The PSC is used in setting the affordability threshold for PPP procurement, which sets the

maximum price the procuring entity wil pay for the project and directly influences decisions

made by respondents in preparing their proposals. Therefore, inputs to the PSC must be

robustly estimated.

Figure 1: Components of the PSC

Tax

Adjustment

Transferred

Risks

Year

Reference

Public

1-5

6

7

8

9+

Project

Sector

Comparator

Construction

($NPC)

and operating

costs if

Net

undertaken by

Present

sset

the procuring

Cost ($)

entity

the A

osts

osts

osts

osts

tion of

C

C

C

C

ing

ing

ing

ing

truc

at

at

at

at

ons

per

per

per

per

C

O

O

O

O

Purpose of the PSC

3.3 The PSC is one of the tools used to assess the appropriateness of procuring the project as a

PPP and is an important benchmark and evaluation tool used during the PPP procurement

process. Additionally, having a detailed understanding of the cost for different scope and risk

items wil enable the procuring entity to make informed judgements about any trade-offs that

may be required during contract negotiations.

The Public Sector Comparator and Quantitative Assessment | 5

OIA 20250193

Item 1

Page 10 of 67

The Reference Project

3.4 Defining the reference project is a critical first step in developing the PSC. The reference

project should reflect the most likely and efficient form of conventional procurement and

service delivery that the procuring entity would use to deliver its whole of life solution for the

project.

3.5 The procuring entity should first determine the outcomes and performance specifications it

requires from the project. The reference project should be designed and its costs estimated

such that it is capable of achieving the same outcomes and performance requirements that

are expected of the private sector under the PPP contract.

3.6 Developing credible cost estimates for the reference project wil usually require the procuring

entity to invest in a level of design documentation, although this may not be required for

projects where alternative methodologies can provide an equivalent level of robustness (for

example, detailed unit cost benchmarks).

3.7 The reference project should:

• Reflect a best practice conventional procurement and service delivery approach.

• Deliver the same level and quality of service that wil be required from the contractor and

include all capital and operating costs associated with designing, building and operating

/maintaining the asset or facilities.

• Recognise the need to coordinate design, construction, operations and maintenance to

optimise whole of life costs.

Transferred Risk

3.8 Examples of transferred risks that the contractor will typically be expected to manage under a

PPP include the risk of not completing the construction of the asset within the cost estimate

or the required timeframes, or not achieving the required operational performance.

3.9 Respondents wil price their proposals taking into account their assessment of the financial

impact of the risks they are required to bear under the PPP contract. Given that many of the

risks to be transferred to the contractor under the PPP wil be borne by the procuring entity in

the reference project, the value of transferred risks must be included in the PSC to ensure a

fair comparison with respondents’ proposals.

Tax Adjustment

3.10 The tax adjustment is designed to remove net competitive advantages that accrue to the

procuring entity by virtue of its public ownership and its exemption from paying income tax. This

allows a fair and equitable assessment between the PSC and proposals received for the project.

Presentation of the PSC

3.11 Robust input data and processing of that data in accordance with this guidance should

produce forecast cash flows and a net present cost that represents the PSC. The forecasts

should be prepared on a monthly or quarterly basis, depending on the phase of the contract

life cycle. For example, monthly forecasting might be appropriate during the construction

and contract start up phases. Quarterly forecasting might be appropriate for the operating

term of the contract. The periods chosen should align with the periodicity of the PBM.

The Public Sector Comparator and Quantitative Assessment | 6

link to page 12 link to page 12

OIA 20250193

Item 1

Page 11 of 67

Process

3.12 PPP procurement is a relatively long process. In this regard the PSC is not a ‘one-time’

calculation and wil need to be monitored during the procurement process and updated at

appropriate milestones if inputs change. Typical milestones include:

•

Business case: as part of the assessment of whether the project can be procured as a

PPP and deliver value for money.

•

Issue of the Request for Proposals (RFP): the PSC should be reviewed and, if

required, updated to assist in setting the affordability threshold to be included in the RFP.

•

During the proposal preparation: The PSC and the affordability threshold should not be

changed once the RFP has been issued to respondents. However, there may be rare

situations where new information comes to light during the proposal preparation process

that is material to the cost assumptions in the PSC

.5 In these circumstances it would be

appropriate to update the PSC to reflect the new information and issue a revised

affordability threshold to respondents. If an update is necessary then it should be

communicated to respondents in a timely manner.

Timing and Economic Assumptions

3.13 The PSC should estimate the cash outflows associated with constructing and operating the

asset over a time period that matches the proposed PPP contract. The key timing and

economic assumptions wil include:

• Discount dat

e6

• Construction period

• Operating period

• Construction costs

• Operating costs

• Construction escalation

• Operating cost escalation

• Labour cost escalation

• Operational commencement

• Operational commissioning period

3.14 Guidance on the discount rate to be used is included in Section 8. The timing of cash flows

should reflect the estimated timing of when payments are made (not accrued) and

discounting conventions should reflect the timing of cash flows within each period (for

example, end of period or mid period).

5

For example, where additional geotechnical investigations being undertaken for, or by, respondents as part of

their due diligence reveals new information that would materially impact on construction costs for the reference

project.

6

The default discount date wil be the anticipated date of Financial Close.

The Public Sector Comparator and Quantitative Assessment | 7

link to page 13

OIA 20250193

Item 1

Page 12 of 67

4 Quantitative Assessment

Introduction

4.1 PPP procurement is only used where it offers value for money over the life of the project,

relative to conventional procurement methods. For the New Zealand PPP model, this means

maximising the service benefits and outcomes of an investment at

no greater cost than if it

were delivered using conventional procurement and service delivery methods.

4.2 Quantitative assessment involves comparing the net present whole of life cost of a PPP

procurement option against the PSC. The assessment is made during the following stages

of a PPP project:

• During the development of the business case by comparing the net present cost of the

PSC against the net present cost of the unitary charge calculated by the PBM. Confidence

that any gap between the PBM and PSC can be offset by the private sector delivering

efficiencies in underlying capital, operating and risk management costs is a prerequisite to

a project being procured as a PPP.

• When proposals are received from respondents in a PPP procurement process by

comparing the affordability threshold to the net present cost of respondents’ proposed

unitary charge payments.

• As a condition to reaching Financial Close by comparing the net present cost of the final

unitary charge to be contractualised against the maximum transaction limit approved by

Cabinet.

4.3 The quantitative assessment is only part of the analysis needed to determine whether a

project should be delivered conventional y or through a PPP. A qualitative assessment

should also be undertaken to consider:

•

Viability: For example, can the service volume and quality required by the procuring

entity be adequately and unambiguously captured in a performance based contract?

•

Desirability: For example, will the incentives and risk transfer incorporated in the PPP

contract produce benefits for the procuring entity that it could not achieve through

conventional procurement?

•

Achievability: For example, does the private sector have the capacity and capability to

deliver the project?

4.4 Further guidance regarding qualitative analysis of PPP procurement is contained in other

guidance published by the Treasury PPP Team.

7

Procuring Entity’s Internal Costs

4.5 The procuring entity wil incur costs procuring the project using its conventional approach and

subsequently managing the contract(s) for the design, build and operation /maintenance of

the project. Similarly, it wil incur costs in undertaking the PPP procurement and managing

the PPP contract.

7

Refer note 4 above

The Public Sector Comparator and Quantitative Assessment | 8

link to page 14

OIA 20250193

Item 1

Page 13 of 67

4.6 If the procuring entity’s internal transaction and contract management costs are forecast to

be higher for PPP procurement than conventional procurement then this cost differential

must be deducted from the PSC for the purpose of setting the affordability threshold and

undertaking the quantitative assessment outlined below. Treating the procuring entity’s

internal costs in this way is necessary to ensure that the total cost of the PPP is no more

than if the procurement and delivery were undertaken using a conventional approach.

Assessment Framework

4.7 PPP projects incur additional costs over and above the costs of conventionally delivered

projects. These additional costs relate to private sector financing and Special Purpose

Vehicle (SPV) costs, and the procuring entity’s additional internal costs that are specific to

PPP procurement. In order to provide a value for money solution to the procuring entity, the

contractor delivering the project through a PPP wil need to offset these additional costs

through construction, operating, or risk management efficiencies. These efficiencies need to

be achieved while delivering the project outcomes to the required standard.

4.8

Figure 2 summarises the framework for assessing value for money. It shows how the

maximum net present cost that the Crown would be wil ing to pay for a PPP project is equal

to the PSC less any additional internal transaction and contract management costs. In order

to recommend PPP as a procurement option, the procuring entity must have confidence that

the private sector can, and wil , deliver the minimum efficiencies required to offset the

additional internal costs of PPP procurement.

Business case analysis

4.9 Quantitative assessment of a PPP is undertaken by comparing the net present cost of the

PSC cash flows against the net present cost of the unitary charge produced by the PBM. For

most projects, the net present cost of the PSC cash flows wil be less than the net present

cost of the unitary charge calculated by the PBM, as the PBM includes private sector

financing and SPV administration costs.

Figure 2: Efficiency gains required

Minimum

private sector

Additional

efficiencies

Maximum

procuring entity

required

Transaction

PPP costs

Limit

Affordability

Threshold

Public Sector

Proxy Bid

Comparator

Model

($NPC)

($NPC)

The Public Sector Comparator and Quantitative Assessment | 9

OIA 20250193

Item 1

Page 14 of 67

4.10 It is difficult to estimate what level of efficiencies the private sector could achieve for a given

project before receiving proposals from respondents. However, using subject matter experts,

it is possible to assess whether the private sector can produce the minimum efficiency gains

required for PPP procurement to deliver value for money. Confidence that the private sector

can deliver these efficiencies is a prerequisite for recommending that a project should be

procured as a PPP.

Approvals

4.11 The recommendation to procure a project as a PPP, together with the net present cost of the

PSC, needs to be formally approved by Cabinet. The recommendation wil be taken to

Cabinet by the relevant responsible Minster for the procuring entity and the Minister of

Finance.

Internal approvals

4.12 The framework and process for internally approving the PSC may differ between procuring

entities. However, it is common for the project governance group, key business lines and the

Chief Executive to all have a role in reviewing and approving the PSC internally.

Cabinet approvals

4.13 PPP projects are typically large and complex projects that create long-term fiscal liabilities for

the Government. Therefore, Cabinet has specific approval rights over the project.

4.14 Procuring entities must seek Cabinet approval of the recommendation to procure the project

as a PPP, together with the PSC. As part of this approval, Cabinet must also approve a

maximum transaction limit, which is the PSC less the net present cost of any additional

procuring entity costs specific to PPP procurement. Cabinet must also approve any change

in the maximum transaction limit after the business case has been approved.

4.15 When approving the business case recommending PPP procurement for the project, Cabinet

may delegate authority to make adjustments to the PSC to joint Ministers (the relevant

responsible Minister for the procuring entity and the Minister of Finance).

4.16 The discount rate used to value the PSC may change over the course of a project (see

Section 6). Therefore, the net present cost of the PSC can change without any of the

underlying nominal costs changing. Discount rate driven changes in the value of the PSC do

not need prior approval from Ministers provided that:

• Treasury is consulted and agrees with changes to the discount rate.

• There are no changes in the underlying nominal costs of the PSC.

• A PPP procurement is stil demonstrated to be value for money in accordance with the

guidance above.

4.17 Given the potential for the present value of the PSC to vary solely due to changes in the

discount rate, all references to net present cost in approval documents should also state the

discount rate used to two decimal places (e.g., $100 mil ion net present cost using a nominal

discount rate of 8.25 percent).

The Public Sector Comparator and Quantitative Assessment | 10

OIA 20250193

Item 1

Page 15 of 67

Setting the Affordability Threshold

4.18 The affordability threshold is the maximum price that the procuring entity is prepared to pay

for the project. It is equal to the PSC less any PPP-specific costs the procuring entity wil

incur over the life of the project. The net present cost of respondents’ proposals must not be

greater than the affordability threshold or the proposal wil be considered non-compliant.

4.19 A robust development process should produce a PSC that the procuring entity can be

confident it could deliver the project within using conventional procurement and delivery

methods. Following the quantitative assessment outlined above, the procuring entity should

also be confident that the private sector could overcome any additional costs incurred as a

result of procuring the project as a PPP and be able to deliver the outcomes required from

the project within the affordability threshold.

Financial Close

4.20 The final quantitative assessment occurs immediately prior to Financial Close. Authority to

bring the project to Financial Close is vested in a nominated official from the procuring entity.

4.21 One of the conditions that must be met before the nominated official can exercise their

authority is that the final unitary charge (incorporating then current interest rates) has a net

present cost no greater than the maximum transaction limit that was approved by Cabinet

prior to commencing the procurement. Advisors should be available to undertake

appropriate analysis and confirm that the condition is met.

The Public Sector Comparator and Quantitative Assessment | 11

OIA 20250193

Item 1

Page 16 of 67

Part Two:

Detailed Guidance

The Public Sector Comparator and Quantitative Assessment | 12

OIA 20250193

Item 1

Page 17 of 67

5 Risk Quantification

Introduction

5.1 Respondents to a PPP procurement process wil price the risks they are expected to bear

under the PPP contract. That is, the price of their proposals wil include allowances for their

estimate of the costs they expect to incur in managing and dealing with risks transferred to

them.

5.2 The PSC must include comprehensive and realistic estimates of the financial impact of all

quantifiable and material risks that the procuring entity would be exposed to under

conventional procurement and delivery methods. This is consistent with the PSC

representing the full cost of the procuring entity delivering the proposed scope of work to be

included in the PPP contract.

5.3 In addition to specific risk events, the PSC must also take into account the risk that volume or

unit cost (rate) inputs used to forecast the total cost of the reference project are materially

inaccurate relative to actual outturn costs. The extent of forecasting inaccuracy will vary

between projects. For example, it might be possible to forecast prices and quantities for

some less complex building projects with a high degree of accuracy. More complex projects,

or projects where certain physical parameters are inherently difficult to forecast, such as

projects with large earthworks and uncertain ground conditions, may have higher levels of

forecasting inaccuracy.

Types of Risk

Systematic and unsystematic risk

5.4 There are two broad categories of risk that need to be considered and accounted for in the

PSC and the PBM:

•

Unsystematic risks (also called unique, specific or diversifiable risks) which are specific

events associated with an individual project (e.g., the risk that ground conditions are

materially worse than thought).

•

Systematic risks (also called market risk or non-diversifiable risk) which result from

economy-wide events that affect all businesses (e.g., the risk that a general economic

downturn renders key sub-contractors insolvent).

5.5 In project risk quantification, unsystematic risks should be quantified in the cash flow

projections through quantitative modelling techniques (for example, sensitivity analysis,

scenario analysis, simulation modelling, Monte Carlo modelling). Systematic risks are

factored into the discount rate and should not be included in the cash flows.

5.6 The remainder of this section discusses how unsystematic risks should be quantified and

included in the PSC cash flows. Section 6 discusses how the discount rate for PPP projects

should be estimated to incorporate the systematic risks that are transferred to the private

sector in a PPP project.

Transferred versus retained risk

5.7 Under a PPP contract, unsystematic risks are transferred to the private sector, retained by

the public sector or shared between both. The procuring entity should transfer all

The Public Sector Comparator and Quantitative Assessment | 13

OIA 20250193

Item 1

Page 18 of 67

unsystematic risks to the contractor unless a better value for money outcome can be

achieved by the procuring entity retaining specific risks. This reflects the principle that each

risk should be allocated to the party best able to manage it for the least cost.

5.8 Risk allocation should be based on the scope of services for the PPP, an assessment of the

ability of each party to reduce the probability and impact of a risk occurring, and the risk

allocation incorporated in the Treasury’s Standard Form PPP Project Agreement.

5.9 Retained risks are those risks that the procuring entity proposes to bear itself under the PPP.

Examples of retained risks include law changes with material capital or operating cost

impacts applying specifically to the project and the risk of obtaining a designation for the

project under the Resource Management Act 1991.

5.10 The procuring entity should identify and quantify all material retained and transferred risks.

However, only transferred risks should be included in the PSC. This is because respondents

to the RFP wil only price the risks that have been transferred to them, so in order for the

PSC to act as a comparable benchmark it must exclude retained risks. Estimates of retained

risks wil be useful for internal project budgeting and for adjusting the PSC if a decision is

made during the procurement process to transfer additional risks to the PPP contractor.

Identifying Risks

5.11 Initially risks should be identified through consideration of precedent projects and in

consultation with the Treasury PPP Team. The list of initial risks should be refined by subject

matter experts, typically through a workshop process attended by relevant procuring entity

staff, advisors and a representative from the Treasury PPP Team. The output of the

workshop is a PSC risk register that should contain as a minimum:

• A description of each risk.

• The timeframe over which the risk may eventuate and whether it is a ‘one off’ or recurring

risk.

• The likelihood of the risk occurring (expressed as a probability percentage).

• The cost if the risk does occur and whether it is a ‘one off’ or recurring cost.

• The basis on which the cost impacts have been established.

• How each risk wil be al ocated under the PPP contract (retained, transferred or shared).

5.12 The workshop process to identify risks requires careful management to ensure that all

relevant risks are identified and described. The workshop wil need to be guided to ensure:

• It focuses on identifying and quantifying risks to the reference project assuming

conventional procurement and delivery methods (risk management benefits available to a

PPP contractor and not the procuring entity should not be included).

• The risk register excludes systematic risks, which are accounted for through the

specification of the discount rate.

• Expert, but subjective, judgements of probability and impact do not suffer from ‘optimism

bias’.

The Public Sector Comparator and Quantitative Assessment | 14

link to page 20

OIA 20250193

Item 1

Page 19 of 67

• Care is taken to not ‘double count’ risks that may already be captured in contingencies

within the underlying cost estimates (it is preferable for these contingencies to be removed

and the risks that they are intending to cover be modelled specifically).

5.13 Appendix A contains high level guidance on the categories of risks that would typically be

included in a risk register for a design, build, finance and maintain PPP (which excludes core

operations from scope) and the allocation of risks between the procuring entity and the

contractor.

Quantifying Risks

Cost impact of individual risks

5.14 The value of transferred risk should reflect the current level of knowledge about the project

and the cost of potential future events occurring during the term of the PPP contract. The

probability and cost impact of a risk occurring wil depend significantly on the nature of the

project. Probabilities and costs for some risks might be lower where the reference project

has been specified to a higher degree.

5.15 The cost impact assessment must be completed from the procuring entity’s perspective.

Only those risks that would have a cost impact on the procuring entity under conventional

procurement and delivery methods (if they were to occur) should be included. Likewise, the

cost impacts should reflect the likely costs that the procuring agency would incur to manage

the risk.

5.16 Events that are considered uninsurable (for example, an act of terrorism or certain

force

majeure events) are generally excluded from the analysis as they are almost always retained

risks and are also either unquantifiable or have a very low probability of occurrence and

therefore wil not have any material impact on modelled outcomes.

5.17 Risks that do have a cost impact should be expressed as a distribution. A common

distribution for quantifying risks is a symmetrical triangular distribution which requires

workshop participants to estimate the minimum, most likely and maximum cost impact of the

risk if it were to occu

r.8 For example:

• The minimum impact may represent a 10% probability that the cost wil be less than or

equal to this amount.

• The most likely impact may represent a 50% probability that the cost wil be less than or

equal to this amount.

• The maximum impact may represent a 90% probability that the cost wil be less than or

equal to this amount.

5.18 The distribution of cost impact for some risks may have a different ‘skew’. These should be

identified and justified during the risk workshops and the probability estimates adjusted

accordingly.

8

Partnerships British Columbia (2014)

Methodology for Quantitative Procurement Options Analysis Discussion

Paper

The Public Sector Comparator and Quantitative Assessment | 15

link to page 22

OIA 20250193

Item 1

Page 20 of 67

Price (rate) and quantity forecasting

5.19 Forecasting the cost of constructing and operating the reference project wil require

assumptions about the quantity and price of materials and inputs. These quantities and

prices will inevitably be subject to inaccuracies when compared with final outturn costs, with

the level of inaccuracy varying depending on the nature of the project and the quality of the

forecasting.

5.20 Where there is a relatively high level of uncertainty, prices and quantities should be

expressed as a range. This might be expressed as an uncertainty range around a point

estimate. For example, $x +/- 10%. This approach enables price and quantity uncertainties

to be modelled and expressed as a distribution and combined with the cost impact

distribution of the specific risks identified in the risk workshop.

Risk modelling

5.21 The approach of identifying cost impacts at different levels of probability means there wil not

be a single estimate of the total risk attributable to the project. The likelihood and cost

impact estimates in the risk register should be used as inputs to a risk model that simulates

potential outcomes. The application of Monte-Carlo simulation, for example, will generate

numerous potential outcome values, which wil allow the risks to be expressed as a

distribution. The following matters should be considered when constructing the risk curves:

• The distribution for each risk.

• The relationship or correlation between individual risks or categories of risks (including

any diversification benefits).

• Whether potential cost impacts are expressed in nominal or real terms.

• How the outputs wil interface with the PSC and PBM models.

• Diversification impacts on the total risk value.

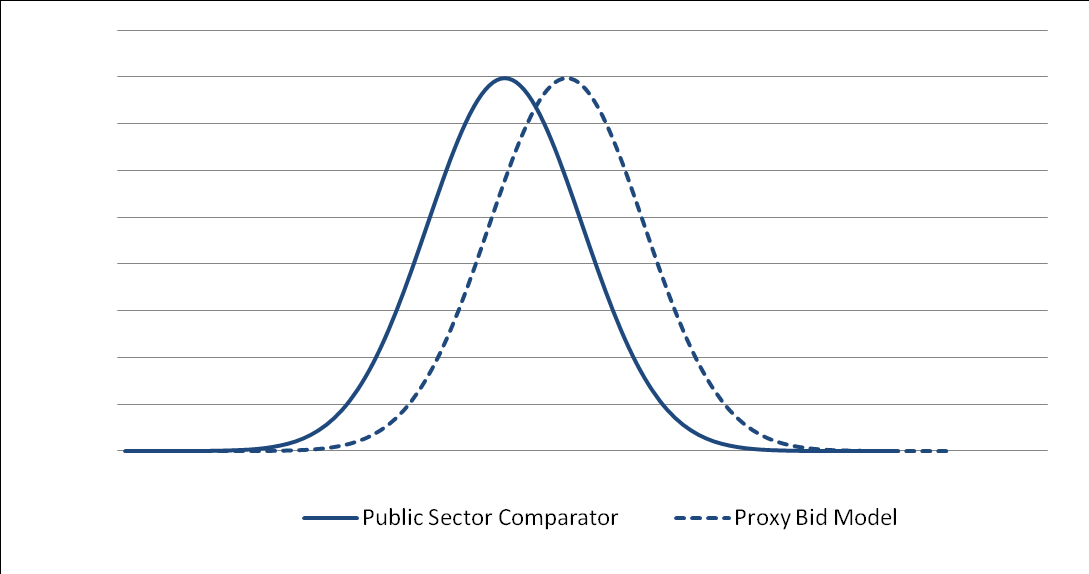

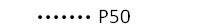

5.22 Adding the risk distribution into the PSC wil convert the PSC into a probability distribution.

For example, the PSC at the P60 level can be interpreted as a 60 percent probability that

actual costs would be less than or equal to the P60 number. The same approach can also

be used to express the PBM as a probability distribution

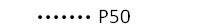

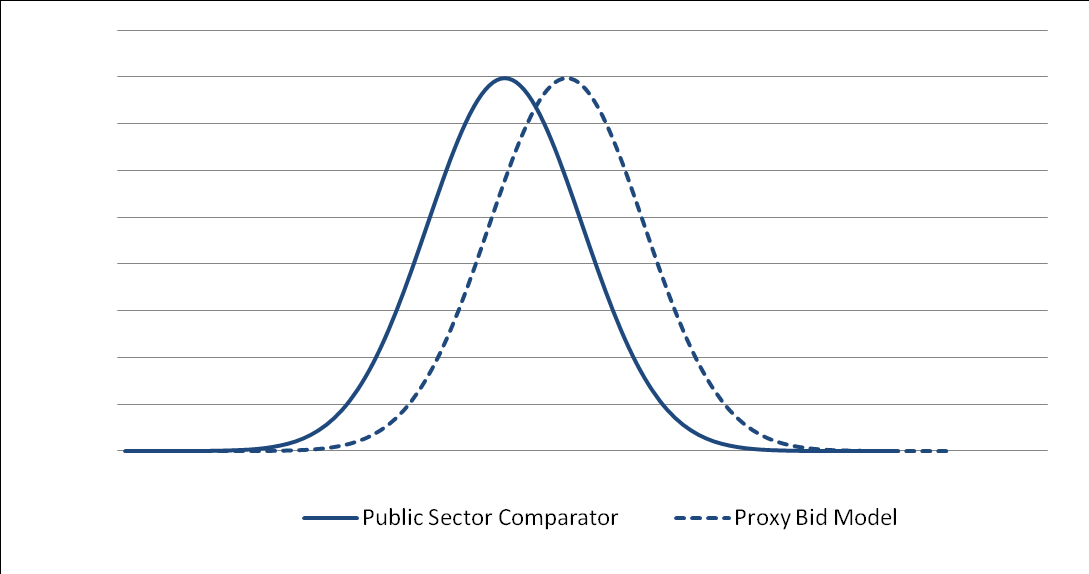

(Figure 3). Expressing both the

PSC and PBM as distributions rather than as point estimates provides further information

about the potential impact of risks on the total cost of the project and the level of efficiencies

the private sector wil need to generate in order to at least match the PSC and provide value

for money.

The Public Sector Comparator and Quantitative Assessment | 16

OIA 20250193

Item 1

Page 21 of 67

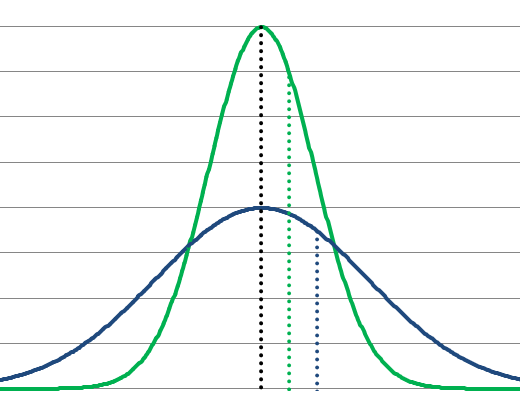

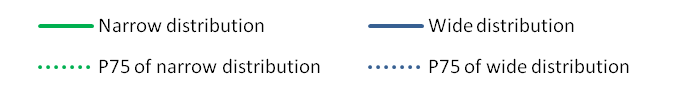

Figure 3: Il ustrative PSC and PBM probability distributions

Net Present Cost

Review of Risk Quantification Outputs for Reasonableness

5.23 Risk modelling results must be reviewed for reasonableness. This might involve:

• Comparing the initial views on risk occurrence and impact with the modelled cash flow

impact on the PSC.

• Testing model outcomes using different distributions to ensure that the profile is consistent

with expectations.

• Comparing the percentage increase in the net present cost of various components of the

reference project as a result of the risk quantification exercise against comparable

precedent projects.

Selecting a Point Estimate for the PSC

5.24 Ultimately, a single point on the distribution curve must be chosen in order to determine a

single point estimate of the PSC. Selecting a point estimate requires an assessment of,

among other things, the level of risk that the procuring entity is prepared to take that the PSC

is above (or below) what the actual outturn cost would be if the project was procured using

conventional methods. The expectation is that the forecasted costs wil always be the result

of a robust analytical process and that, all other things being equal, point estimates should

be within the P50 to P75 range.

5.25 Selecting a point estimate with a higher P-value wil provide greater certainty that the actual

outturn cost would be less than or equal to the PSC. However, given that the New Zealand

PPP model encourages respondents to the RFP to maximise the quality of outcomes within

the affordability threshold (based on the PSC), selecting a higher P-value upon which to base

the point estimate of the PSC wil mean that the cost of the project to the procuring entity is

likely to be higher (but also that the quality of outcomes should increase accordingly).

Selecting a point estimate with a lower P-value wil reduce the costs to the procuring entity,

but increase the risk that the affordability threshold wil be set too low for respondents to

deliver the desired outcomes.

The Public Sector Comparator and Quantitative Assessment | 17

OIA 20250193

Item 1

Page 22 of 67

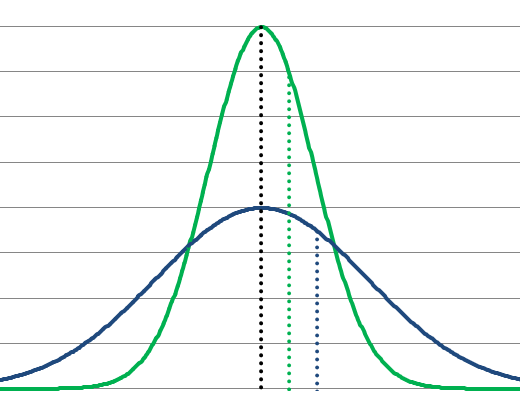

5.26 Consideration should also be given to the shape (standard deviation) of the PSC distribution.

Cost in a ‘wide’ distribution wil be more sensitive to changes in the P-value than cost in a

‘narrow’ distribution. Figure 4 il ustrates that the net present cost at P50 is the same

regardless of the shape of the distribution but that the net present cost of the P75 point

estimate is lower in a narrow distribution than in a wide distribution.

Figure 4: Net present cost sensitivity to changes in probability (P-value)

Location of P75 value on point estimate distribution curve P-Value vs Net Present Cost of two distributions

Density

lue

Probability

P-Va

Net Present Cost

Net Present Cost

5.27 Factors that influence the shape of the distribution include the level of inaccuracy assumed in

the procuring entity’s price and quantity forecasts (with greater inaccuracies widening the

distribution) and the level of knowledge about the treatment for specific risks. Procuring

entities can reduce the variability of forecast point estimates by developing the design detail

of the reference project, thereby increasing the accuracy of price and quantity forecasts, and

treatments for specific risks.

The Public Sector Comparator and Quantitative Assessment | 18

link to page 24

OIA 20250193

Item 1

Page 23 of 67

6 Proxy Bid Model

Introduction

6.1 The PBM represents the cost of the risk adjusted reference project with the addition of

private sector financing, tax and PPP specific costs.

9 The PBM calculates the estimated

periodic amount (the unitary charge) that a contractor would require as payment for

delivering all of the services and providing the financing required for the project.

Figure 5: Components of the Proxy Bid Model

Proxy Bid Model

Financing

Costs

SPV Admin

Tax Costs

Transferred

Risks

Reference

Uses the

Project

same inputs

as the PSC

Construction

Unitary Charge

and lifecycle

Net

Year

capital and

Present

1 5 10 15 20 25 30

operating costs

Cost ($)

6.2 As a result of additional private sector costs, the net present cost of the PBM will be higher

than the PSC. This difference between the PSC and the PBM provides an indication of the

efficiencies that the contractor would have to find in order to deliver the project at a net

present cost equal to or less than the PSC. The contractor will also need to find further

additional efficiencies to in order to offset the procuring entity’s additional internal PPP

procurement costs in order to deliver the project within the affordability threshold (refer

Figure 2).

6.3 The key outputs from the PBM are:

• The periodic unitary charge over the term of the PPP project agreement.

• The present value of the unitary charge in order to undertake the quantitative assessment

described in Section 4.

9 For example, SPV administration costs and the costs of developing proposals.

The Public Sector Comparator and Quantitative Assessment | 19

link to page 25

OIA 20250193

Item 1

Page 24 of 67

• Information needed to model the impact of the PPP on the procuring agency’s financial

statements and funding requirements. The PBM can be ‘solved’ such that its net present

cost equals that of the PSC. The unitary charge of the ‘solved’ PBM can be used to

provide guidance to the procuring entity on the potential annual costs of the PPP that it

wil have to fund.

Methodology

6.4 The PBM takes all of the input costs from the PSC, including capital and operating costs and

quantified risks, and uses current financial market interest rates, observable interest margins,

equity returns and gearing levels to derive an appropriate financing structure for the project.

6.5 The critical inputs in the PBM not included in the PSC are the financing assumptions. The

PBM is typically modelled assuming funding is provided on a non-recourse basis to a SPV.

10

6.6 The PBM should be developed in line with the following steps:

• Project operating revenues (if any), operating expenses and capital expenditure are used

to generate operating cash flows for the project.

• PPP specific costs such as SPV administration costs are added to the PSC costs.

• Debt, equity and taxation cash flows that broadly reflect current market conditions are

added to the operating cash flows.

• The unitary charge is calculated to meet all of the costs of the project, including taxation

and the required return on, and return of, debt and equity capital.

Cost, Timing and Economic Assumptions

6.7 The PBM uses the same cost, timing and economic inputs as used in the PSC. That is, the

same base capital and operating costs, risk adjustments and escalation profiles apply to the

PBM as to the PSC.

Forecasting periods

6.8 Monthly forecasting wil generally be appropriate during the construction period. The period

convention during the operating term of the contract wil be determined by a number of

factors but primarily the financing structure, particularly the debt facilities, and the anticipated

frequency of unitary charge payments. For example, if the interest rate for one or more of

the contractor’s debt facilities is referenced to the 90 day bank bil rate then modelling wil be

required on a quarterly basis (strictly 90 day periods) to provide accurate calculations of

interest rate costs.

10 The SPV wil most likely be a limited liability company or limited partnership. In a typical structure the SPV wil

contract with a construction sub-contractor to build the asset and an operator to operate and maintain the asset.

It will borrow in its own right to pay the construction sub-contractor for building the asset. The debt and equity

funding wil be advanced to the SPV by investors on the strength of the payments that the SPV wil expect to

receive under its contract with the procuring entity.

The Public Sector Comparator and Quantitative Assessment | 20

link to page 26

OIA 20250193

Item 1

Page 25 of 67

Financing Assumptions

6.9 Overall structural assumptions need to be made for the financing approach adopted in the

PBM. For example:

• Financing cash flows during the construction period: A reasonable assumption, consistent

with recent PPP projects, is that the cash outflows during construction are financed firstly

with debt, with equity to be contributed after all debt is drawn down. However, equity is

committed from commencement of the PPP contract with consequential fees being paid to

the equity providers.

• Construction debt interest: Capitalised through to the end of construction when it is

incorporated into a term debt facility.

• The term facility refinancing: Refinanced with a bullet repayment that pays down the

balance of the outstanding debt with a new term facility on nominated refinancing dates.

6.10 The Treasury PPP Team maintains a record of financing terms observed in all PPP

procurement processes to date and should be consulted on appropriate assumptions to be

applied to individual projects.

Gearing levels

6.11 PPP projects are typically highly geared. A high level of debt in the financing structure for a

PPP wil be cost effective (the return on debt is lower than the return on equity). A debt to

equity ratio of 85:15 would not be unusual for a PPP.

6.12 The maximum level of debt wil be a function of debt sizing criteria agreed between the

contractor and its lenders. Debt sizing criteria wil typically include a maximum gearing ratio

(debt as a percentage of debt plus equity) and a maximum Debt Service Coverage Ratio

(DSCR). The DSCR is the ratio of cash available for debt servicing to debt service costs,

inclusive of interest and fees. The maximum gearing ratio and DSCR constrain debt to a

level that can be serviced with an acceptable cash flow buffer.

Debt tenor

6.13 The debt facility during construction will typically be in place for the entire construction period

and wil convert into a term facility at, or near, the end of construction (it may include the lock

in period).

11 Re-financing of the term facility will occur periodically where the tenor of the

underlying debt is shorter than the contract term.

6.14 The available tenor of debt facilities in New Zealand is relatively short by international

standards. This means that multiple re-financings of the term debt might be required.

6.15 The debt tenor is important because fees wil be charged at each refinancing. These fees

need to be accounted for in the unitary charge calculation, as the unitary charge needs to

provide sufficient cash to cover fees as well as interest payments and principal repayments.

11 Equity investors are restricted from selling their equity stake in the project during the lock-in period, typically

ending 12 months following Service Commencement.

The Public Sector Comparator and Quantitative Assessment | 21

OIA 20250193

Item 1

Page 26 of 67

The cost of debt financing

The cost of debt can be specified according to the following formula:

𝑅𝑑 = 𝑏 + 𝑚 + 𝑓

Where:

𝑏 = base interest rates.

𝑚 = interest rate margin.

𝑓 = debt issuance costs and other financing fees.

Base interest rates

6.16 The default approach to debt financing expected in all PPP projects is:

• The contractor wil be required to provide the procuring entity with a fixed base interest

rate for the duration of the construction period and the lock-in period (initial hedge period).

• After the initial hedge period, the contractor wil not be required to provide a fixed interest

rate unless it can do so for the entire term of the senior debt (noting that debt is typically

fully repaid before the expiry of the PPP contract). In the absence of the private sector

providing a long-term fixed interest rate solution, the contractor wil be paid on the basis of

floating interest rates (typically the 90 day bank bil rate). Hedging requirements for the

term of the contract after the end of the lock-in period wil be subject to separate

arrangements between the Treasury and the procuring entity and wil not involve the

contractor.

6.17 The base interest rates to apply will be:

• A base swap rate matching the duration of the initial hedge period.

• The base interest rate forecast to apply after the initial hedge period wil be provided by

the Treasury PPP Team. These forecasts may change over the course of a PPP

procurement process in response to changes in market conditions, including leading up to

Financial Close.

Interest rate margins

6.18 Interest rate margins (credit margin over the base interest rates) can be estimated by

reference to margins applied in recent PPP projects and taking into account current market

conditions. The margins should be assumed to reduce following completion of construction,

to reflect a reduction in exposure to design and construction related risks.

Financing Fees

6.19 Fees wil be payable in relation to equity and debt finance. Consistent with recent market

trends, the following types of financing fees should be included in the calculation of the

unitary charge:

• Arrangement fees paid at Financial Close, expressed as a percentage of the total debt

facility size.

The Public Sector Comparator and Quantitative Assessment | 22

link to page 28

OIA 20250193

Item 1

Page 27 of 67

• Commitment fees, which are a percentage to be paid quarterly on undrawn debt facility

balances. The fee rate wil be expressed annually but paid quarterly.

• Refinance fees, which are assumed to be ‘one off’ fees paid after the committed facility

matures at each refinancing event.

Repayment profile

6.20 The term facility debt can be amortised using a credit foncier repayment profile ‘sculpted’ to

take into account the project’s DSCR requirements. This method of amortisation provides

flexibility around repayments so they can vary in accordance with lumpy expenditure such as

lifecycle maintenance expenditure. The sculpted debt approach is common to projects of

this nature.

6.21 Depending on the nature of the project, it may be appropriate to incorporate a Debt Service

Reserve Account (DSRA). This wil typically hold a balance equivalent to a number of

months of future debt service obligations. The initial balance of the DSRA would be funded

through the construction facility.

6.22 The alternative is to establish a debt service reserve facility. This wil incur fees, similar to

the other debt facilities incorporated into the capital structure, as opposed to interest costs

associated with establishing a funded DSRA.

Target equity return

6.23 The target post-tax equity IRR underpins the calculated level of the unitary charge. The PBM

calculates a unitary charge that provides sufficient cash to meet the post-tax equity IRR after

operating costs, debt service costs and any SPV taxation. The target post-tax equity IRR

should be set taking into account general market conditions, by reference to appropriate

evidence of investor returns and in consultation with the Treasury PPP Team.

Taxation Calculations

6.24 If the SPV is a limited liability company then it wil pay tax on assessable income. If the SPV

is a limited liability partnership then assessable income wil be taxed in the hands of the SPV

investors. The unitary charge needs to deliver sufficient cash to cover the tax costs, whether

they are incurred at the SPV or investor level.

6.25 A tax calculation wil be required as part of the unitary charge calculations. A tax calculation

wil also be required to produce the tax adjustment discussed in Section 7.

6.26 The tax calculations should take into account the contractual structure incorporated into the

Treasury Standard Form PPP Project Agreement and be consistent with the IRD’s Public

Rulings on the PPP contractual framework and any subsequent future rulings.

12

Goods and Services Tax

6.27 The inputs to the PBM should be exclusive of Goods and Services Tax (GST). This will

produce a unitary charge exclusive of GST.

12

http://www.ird.govt.nz/technical-tax/public-rulings/2013/public-ruling-13005-13006.html

The Public Sector Comparator and Quantitative Assessment | 23

OIA 20250193

Item 1

Page 28 of 67

6.28 GST cash flow timings may have a working capital impact. RFP respondents wil model GST

flows and incorporate the financing cost of any timing issues into the unitary charge.

However, the impact on the unitary charge is unlikely to be material so GST modelling will

not usually be undertaken for the PBM.

Unitary Charge Profile

Indexation

6.29 The unitary charge can be modelled on the basis it wil be escalated in line with forecast

escalation of the underlying costs. However, different costs are likely to escalate at different

rates which means the escalation rate applied to the unitary charge wil need to represent a

weighted average of the underlying cost escalation rates.

6.30 Typical indices that escalation rates are derived from are:

• Consumer price index (CPI), to reflect general inflation in operating costs.

• Labour cost index (LCI), to reflect inflation in personnel costs.

6.31 Not all of the unitary charge wil be adjusted for cost escalation. A component wil be fixed

and not escalated. The fixed component wil usually represent the proportion of the unitary

charge to be applied to servicing the capital used to construct or deliver the project.

6.32 Some financing structures incorporate indexed equity. For example, where a component (or

all) of the outstanding equity at the end of each period is indexed to CPI with a consequential

impact on the unitary charge.

Maintenance Reserve Account

6.33 Operating expenditure wil be comprised of both costs that wil not change significantly from

period to period and costs that wil be volatile or ‘lumpy’. Lifecycle maintenance expenditure

wil typically be the primary cause of significant spikes in the unitary charge.

6.34 The variability in expenditure caused by lifecycle maintenance and other lumpy expenditure

can be incorporated unadjusted from the PSC into the unitary charge. This wil result in a

lumpy unitary charge profile.

6.35 Alternatively, the unitary charge can be smoothed to remove the variability caused by the

lumpy expenditure. This is achieved by assuming that the SPV will deposit cash into a

designated reserve account over time and draw on this to fund subsequent lumpy lifecycle

maintenance expenditure. Senior debt repayments wil be sculpted around movements in the

reserve account balances.

6.36 There wil be a financing cost to the procuring entity of using a reserve account to smooth the

impact of lumpy operating expenditure on the unitary charge. In comparison, there wil not

be any financing cost within the PBM if the lumpy expenditure is passed through to the

unitary charge with no smoothing. Therefore smoothing is unlikely to provide value for

money and is not recommended unless stability of cash flow is important for the procuring

entity.

The Public Sector Comparator and Quantitative Assessment | 24

link to page 30

OIA 20250193

Item 1

Page 29 of 67

7 Tax Adjustment

Introduction

7.1 Private sector respondents for a PPP contract wil be taxpayers, whereas public sector

entities do not usually pay tax. A tax adjustment is included in the PSC to minimise the

impact of differences in tax status to ensure a fair comparison between the PSC and private

sector PPP proposals.

Impact of Taxation

7.2 The unitary charge wil be calculated to provide the PPP contractor with sufficient cash to:

• Pay interest at pre-tax rates.

• Pay any tax incurred by the SPV.

• Make distributions to equity providers that wil allow them to pay any tax they incur on

those distributions and provide them with their required post-tax return.

7.3 Consequently, the unitary charge wil be sufficient to pay all tax on the returns on the capital

(debt and equity) provided to finance the construction of the asset and any other investment

needed during the contract term, and provide the debt and equity investors with their

required post-tax rates of return

.13

7.4 In contrast, public entities are generally not taxpayers. Therefore, the PSC cash flows do not

include any explicit tax outflow for returns on the capital provided to finance the construction

of assets. This difference in tax status is one of the reasons why the PSC cash flows wil be

different to the cash flows that drive the unitary charge calculation in the PBM.

Rationale for Adjustment

7.5 The difference in tax status between the procuring entity and the private sector participants in

a PPP provides the PSC cash flows with a cost advantage compared to the unitary charge.

However, the tax status difference is a function of policy and legislation. It is not something

that private sector entities can change or influence in the context of pricing a proposal for a

PPP contract. Furthermore, because the component of the unitary charge attributable to tax

to be paid by the debt and equity investors wil eventually be returned to the Crown when the

tax is paid, it should not be a factor that influences the choice of procurement.

7.6 Taxes other than income tax on investment returns (for example, tax on construction

company profits) are likely to be the same under either a conventional procurement or a PPP

so their impacts do not need to be neutralised.

13 It wil also provide sufficient cash to pay for the operating costs, lifecycle maintenance and the return of capital to

the investors.

The Public Sector Comparator and Quantitative Assessment | 25

OIA 20250193

Item 1

Page 30 of 67

Adjustment Process

7.7 The impact of the difference in tax status needs to be neutralised to enable a fair comparison

between the PSC and the PBM (and the price of private sector proposals). This could be

achieved by calculating the present value of the PSC and the unitary charge using a pre-tax

discount rate, reflecting that the PSC cash flows and the unitary charge are, in effect, pre-tax

cash flows.

7.8 However, the discount rate used to calculate the present value of the unitary charge and the

PSC cash flows is specified, in the first instance, as a post-tax weighted average cost of

capital (WACC).

7.9 WACC is specified on a post-tax basis because, among other reasons, some of its key

parameters can only be observed on a post-tax basis. Furthermore, it is not appropriate to

simply gross-up the post-tax discount rate using the corporate tax rate (28%), as forecast

cash tax in each year is unlikely to be 28% of the pre-tax cash flows (because of timing and

permanent tax differences) and the forecast period is finite.

7.10 Therefore, the following process needs to be followed to correctly estimate the present value

of the tax adjustment:

• Calculate the present value of the PSC cash flows using the post-tax discount rate (post-

tax WACC).

• Calculate the tax payable on SPV pre-financing earnings (cash flows available to the

providers of debt and equity) in the PBM.

• Calculate the present value of the tax payable (calculated in 2) using the post-tax discount

rate.

• Adding the present value of the tax payable (calculated in 3) to the present value of the

PSC cash flows (calculated in 1).

The Public Sector Comparator and Quantitative Assessment | 26

OIA 20250193

Item 1

Page 31 of 67

8 Discount Rates

Introduction

8.1 The discount rate is used to calculate the present value of the:

• Forecast capital and operating costs (both inclusive of quantified transferred risks) in the

PSC.

• Unitary charge in the PBM.

• Tax adjustment to the PSC.

• Unitary charge proposed by respondents.

8.2 The present values are used for a number of purposes and at various times during the

procurement process. In particular:

• The present values of the PSC forecast costs and the PBM unitary charge are used as

inputs into the assessment of the appropriateness of procuring the asset or service

through a PPP.

• The present value of the PSC is used to set the affordability threshold for disclosure in the

RFP.

• The present value of each respondent’s proposed unitary charge is used to test that they

are less than or equal to the affordability threshold.

• Monitoring the present value of the preferred bidder’s unitary charge during the preferred

bidder stage to ensure that the present value of the unitary charge remains below the

approved transaction limit leading up to, and at, Financial Close.

8.3 A consistent discount rate specification must be used for all present value calculations to

ensure that the analyses, assessments and decisions being made on the basis of the

present values are robust and have integrity. The discount rate should reflect the cost of

capital for the project, adjusted for the systematic risks that the private sector is expected to

bear under the PPP contract.

The Discount Rate Model

8.4 A procuring entity considering investment in an asset to deliver services faces two important

decisions:

•

Investment decision: Whether it is sensible to invest in the asset in the first instance.

This wil require consideration of, among other things, whether society is better off

foregoing current consumption and reallocating resources to investment in the asset. The

assessment required for this decision is focused on the relationship between economic

benefits and economic costs.

•

Procurement decision: If the cost benefit analysis concludes that investment is

appropriate, the next decision is how to procure the asset and the associated services. In

the context of this document the decision is between conventional procurement or PPP

procurement.

The Public Sector Comparator and Quantitative Assessment | 27

link to page 33 link to page 33

OIA 20250193

Item 1

Page 32 of 67

8.5 The analysis at both of these decision points requires present values of benefits and costs or

revenues and expenditure to be calculated using appropriate discount rates. The

appropriate discount rate to use for the investment decision should be developed in

consultation with the Treasury PPP Team and in accordance with published guidance.

14

8.6 The procurement decision can be characterised as the procuring entity determining what

delivery approach wil provide the best combination of quality of service, management of

project risk and cost effectiveness. Value for money is an important component of the

procurement decision. The discount rate is used to calculate and compare the present day

cost of procuring a project as a PPP and procuring the project using conventional methods.

Risk adjusted cost of capital

8.7 A fundamental principle underpinning the calculation of the discount rate for the procurement

decision is that it should reflect the marginal cost of capital for the project. That is, a cost of

capital that is based on the returns of alternative investment opportunities with similar risk

profiles to the project

.15

8.8 The rate at which the government can borrow from financial markets (the risk free rate) is not

an appropriate discount rate for the procurement decision. The risk free rate reflects that

lenders to the government are not exposed to risks relating to the performance of public sector

investments and have their rate of return underpinned by the government’s power to tax.

8.9 The risk free rate does not adequately reflect risk that wil be borne by investors in a project,

regardless of whether it is the procuring entity or the private sector through a PPP. In

contrast, respondents to an RFP wil be pricing their required rates of return on investment

capital to reflect the risk of their investment in the project. Using the risk free rate to discount

the PSC would be inconsistent with the true cost of capital for the project and the cost of

financing the project as a PPP. Consequently, the quantitative assessment would be biased

against procuring a project as a PPP.

14 http://www.treasury.govt.nz/publications/guidance/planning/costbenefitanalysis/

15 For a more extensive discussion of this principle see

Discussion Paper: Methodology for Quantitative

Procurement Options Analysis available at

http://www.partnershipsbc.ca/files-4/guidance.php

The Public Sector Comparator and Quantitative Assessment | 28

link to page 34 link to page 34

OIA 20250193

Item 1

Page 33 of 67

Specification of the Discount Rate

8.10 A single discount rate specification is to be used in all present value calculations. This is to

be calculated as a post-tax, nominal WACC usi

ng Equation 1. This is a standard

specification of the cost of capital used widely in New Zealand.

Equation 1: Weighted average cost of capital

𝐷

𝐸

𝑊𝐴𝐶𝐶 = 𝑅𝑑 × (1 − 𝑇𝑐) × 𝑉 + 𝑅𝑒 × 𝑉

Where the variables are:

𝑅𝑑

The pre-tax cost of debt (comprised of base interest, credit risk

margin and other debt issuance costs).

𝑇𝑐

The prevailing corporate tax rate.

D, E and V

The market values of debt and equity respectively.

V is the sum of

D and

E. Therefore, 𝐷 and 𝐸 represent the relative weighting of