Risk Assessment, Strategy and Tactics

Section 3: Risk Assessment, Strategy and Tactics

Section Contents

Section 3: Risk Assessment, Strategy and Tactics ............................................................................................ 1

Act

Risk Assessment, Strategy and Tactics .............................................................................................................. 1

3.1 The decision-making hierarchy ................................................................................................................. 1

3.2 Incident action planning ............................................................................................................................ 7

3.3 Selecting STRATEGY: key principles ..................................................................................................... 20

3.4 Selecting tactics and tactical modes ....................................................................................................... 22

3.5 Safe Person Concept .............................................................................................................................. 30

3.6 Dynamic Risk Assessment ..................................................................................................................... 34

3.7 Snap rescue ............................................................................................................................................ 42

3.8 Sectorisation ........................................................................................................................................... 44

3.9 The NZFS Agency Action Plan (AAP) ..................................................................................................... 50

Information

Official

the

under

Released

January 2013

i

Act

Information

Official

the

under

Released

Risk Assessment, Strategy and Tactics

Section 3: Risk Assessment, Strategy and Tactics

Introduction

This document is Section 3 of the New Zealand Fire Service (NZFS) Incident

Management – Command and Control Technical Manual.

Act

Risk Assessment, Strategy and Tactics

3.1 The decision-making hierarchy

3.1.1

It is important to understand that effective decision-making has to occur at a

Information

number of levels if an incident is to be managed successfully. Emergency

services personnel will use a wide range of methods for arriving at decisions,

but whatever the method, they must arrive at a clear understanding of:

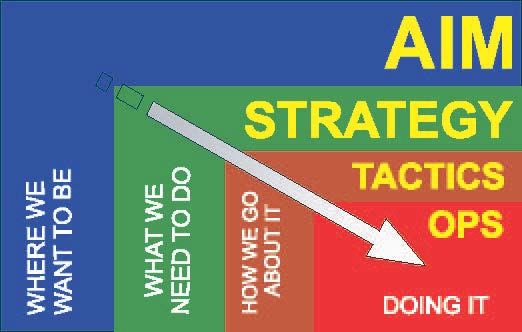

• AIM

• STRATEGY Official

• TACTICS

• Operational TASKING.

the

3.1.1.1 AIM

The AIM is a concise, clear and simple understanding of the eventual outcome,

based on the NZFS Mission Statement.

‘What do we want to achieve?’

under

Released

January 2013

1

Incident Management – Command and Control

3.1.1.2 STRATEGY

The STRATEGY is the most effective, efficient and safe approach available to

us within the limitations of our resources and skills.

‘What we need to do’.

Examples of possible strategies are:

• Prevent property damage (smoke and water)

• Rescue occupants

• Administer first aid

Act

• Extinguish the fire

• Not extinguish the fire

• Restrict access/evacuation

• Protect the environment

• Firefighter safety.

3.1.1.3 TACTICS

The TACTICS are the specific actions we need to take to make our

Information

STRATEGY work.

‘How we go about it’.

Examples of possible tactics are:

• Offensive internal fire attack

Official

• Defensive external fire attack

• Salvage

the

• Formalise C&C

• Ventilation

• Establish water relay

• Cordon area

under

• Supported search and rescue BA teams

• Set up triage

• Decontamination.

3.1.1.4 Operational

Operational TASKING is the detailed decisions concerning the tasks that need

TASKING

to be performed to make the TACTICS work.

Released ‘Doing it’.

Examples of possible tasking are:

• BA crew no 1, low pressure delivery, 2nd floor, internal fire attack

• Salvage and ventilation crew, ground floor, with salvage sheets, restrict

water damage.

2

New Zealand Fire Service – National Training

Risk Assessment, Strategy and Tactics

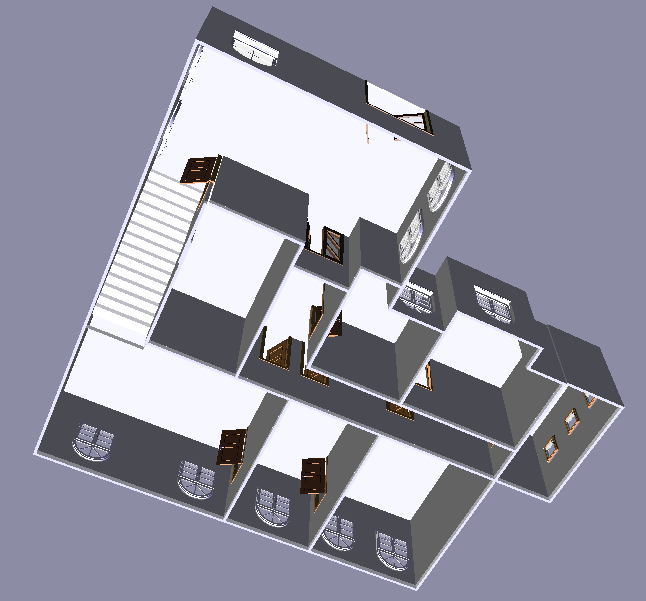

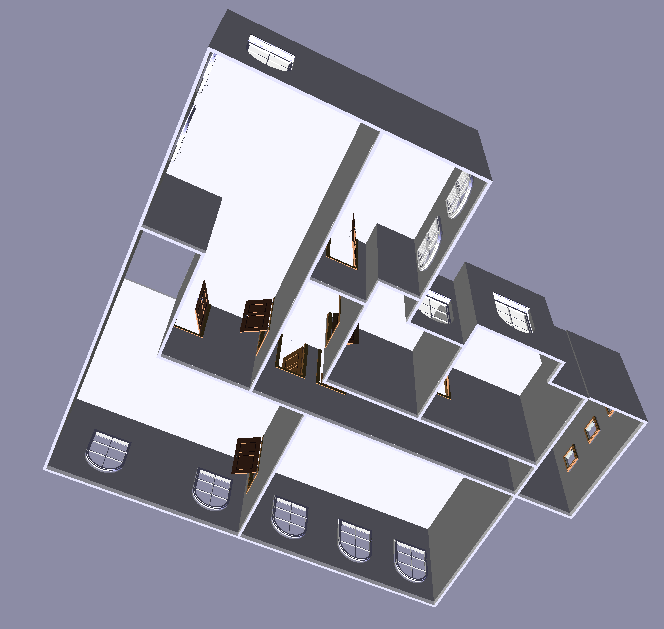

3.1.2

Risk Assessment, Strategy and Tactics

3.1.2

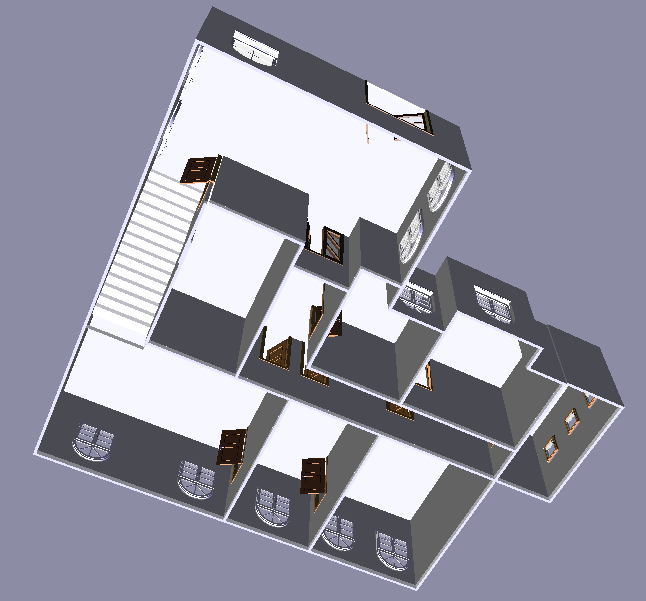

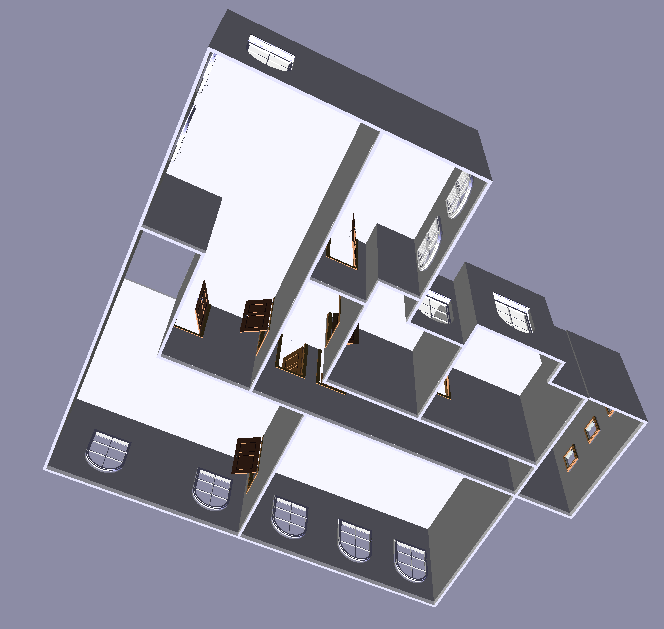

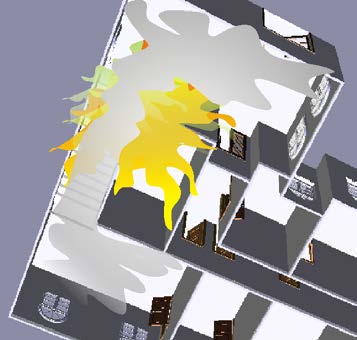

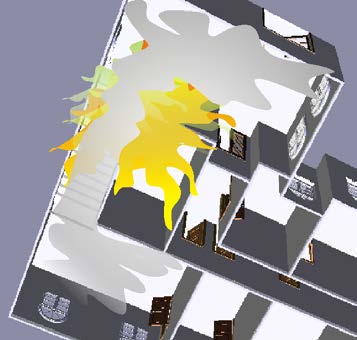

Decision-making on the incident ground is an example of hierarchical thinking

with everything deriving ultimately from the AIM. The model shown in Figure

3.1 below illustrates this hierarchy.

Act

Figure 3.1: Decision-making Hierarchy

Information

(Source – NZFS 2006)

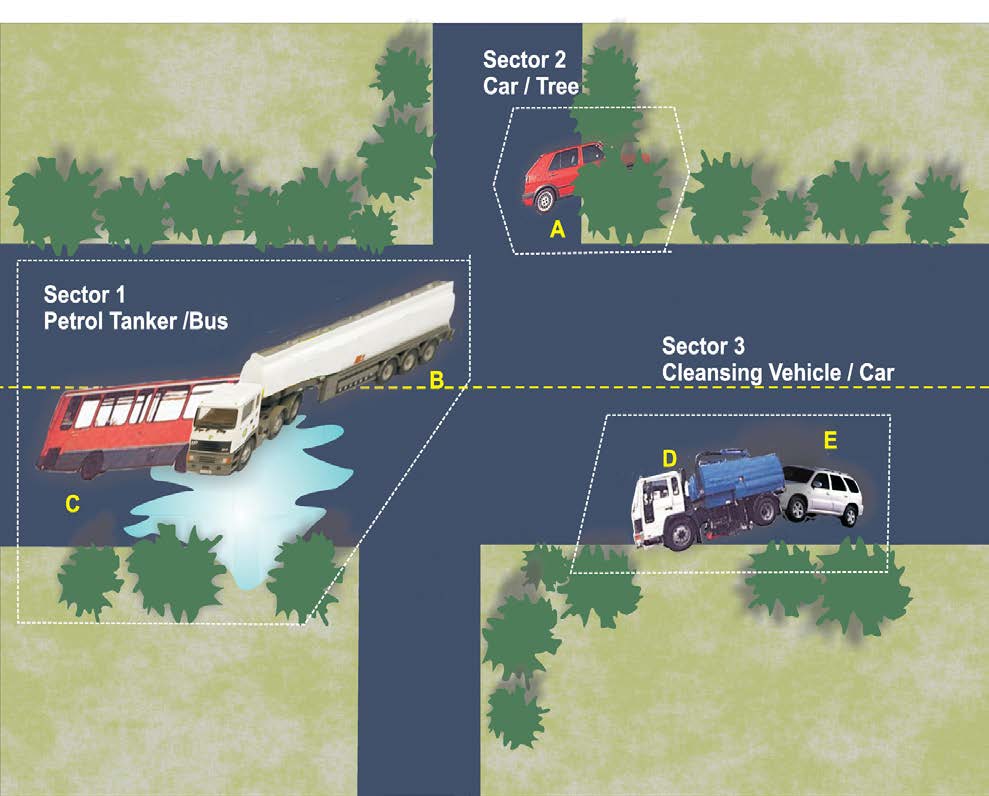

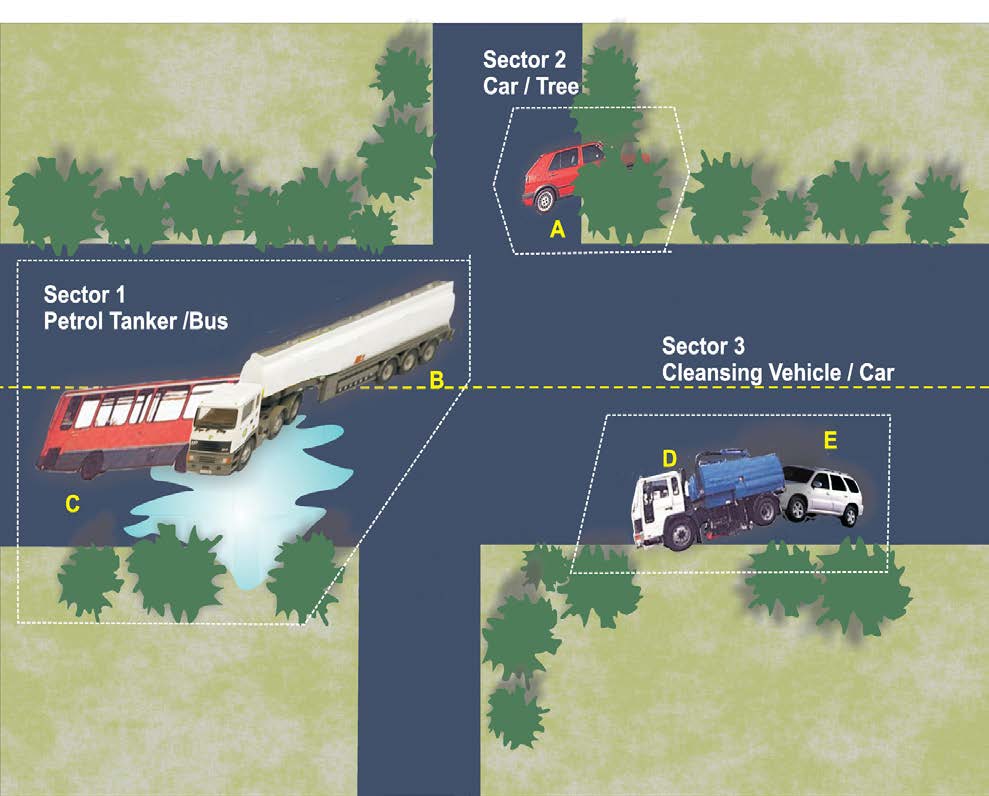

3.1.3 Example scenario

There is a tendency to assume that all incidents are governed by the single AIM

‘to save life and protect property,’ and that we need not do any more thinking

than that. In fact the AIM (and the STRATEGY and TACTICS that flow from

it) may need to be more specific, or perhaps broken into staged priorities. The

Official

simple scenario below illustrates this.

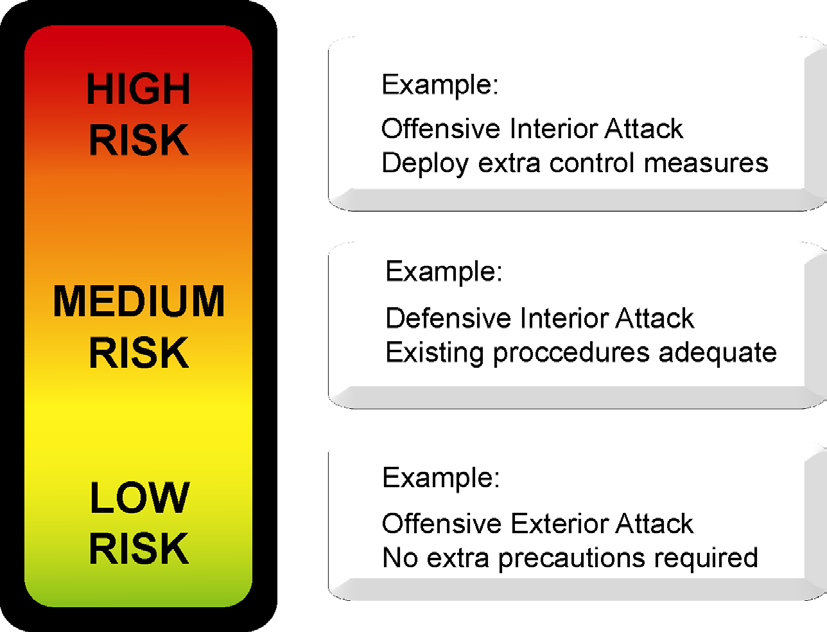

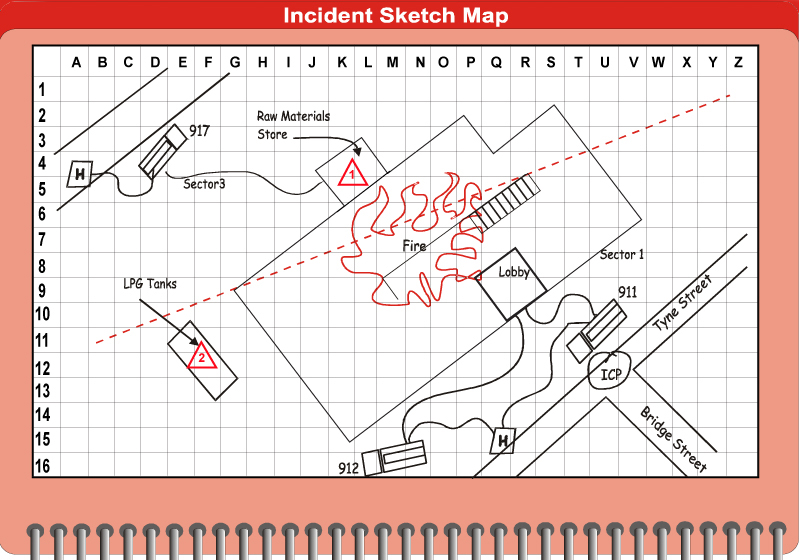

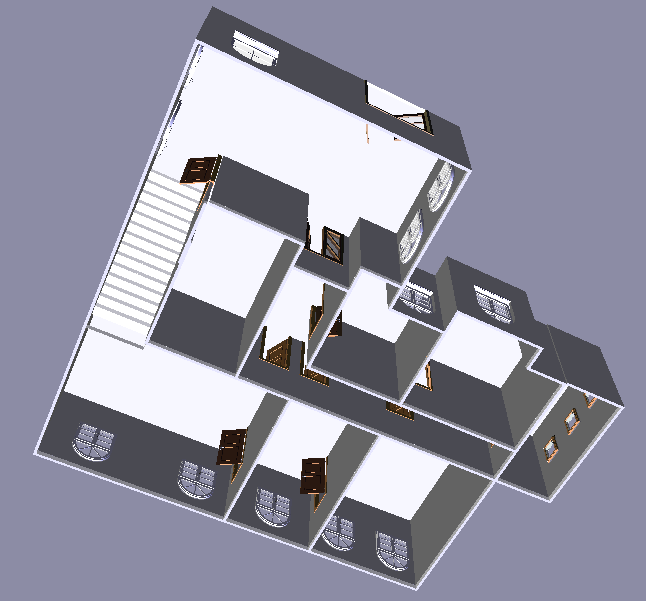

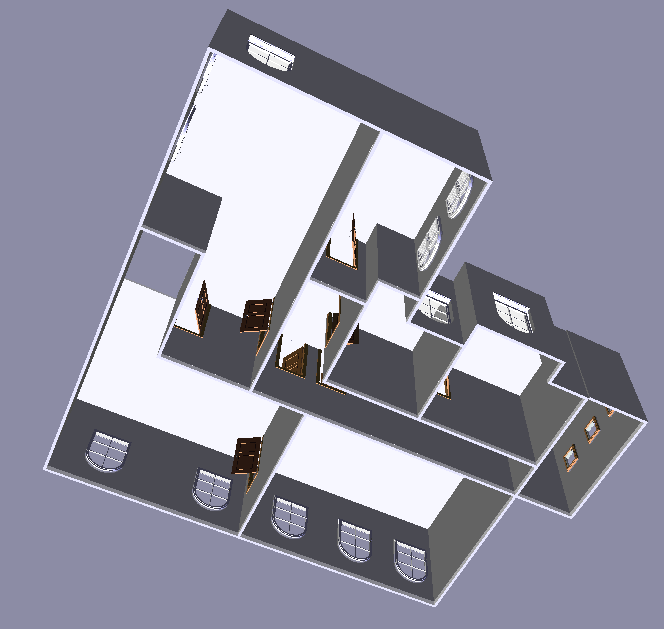

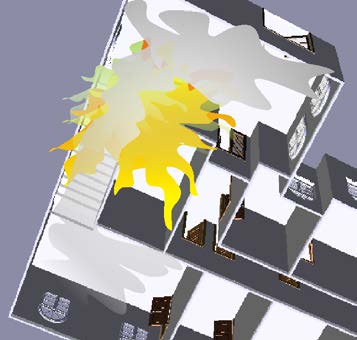

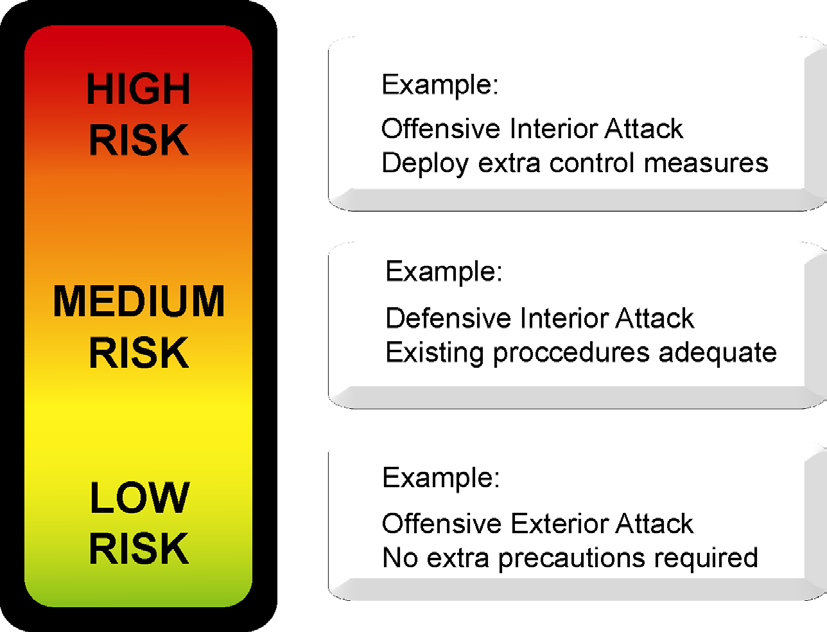

3.1.3.1 Location

The location is a multi-gallery city arts museum. The museum houses

the

collections of regional paintings and sculpture of local interest but of no

exceptional value. The building, however, is 120 years old and listed as being

of heritage value. Operational planning focuses primarily on saving the

building as a priority rather than preventing possible damage to the contents.

3.1.3.2 Situation

In addition to its usual displays, the Museum is currently showing a travelling

under

exhibition of six paintings by Picasso in an upstairs gallery. The paintings are

irreplaceable and their monetary value is conservatively estimated at around

NZ$80,000,000. Unfortunately the NZFS was not advised regarding the

exhibition and has not amended its risk plan in any way.

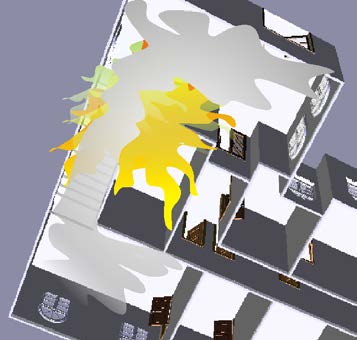

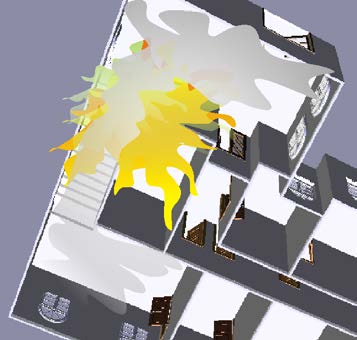

Fire has broken out on the ground floor. Two galleries and the central staircase

are well involved. There is no lift. The picture galleries are not sprinklered

because of the risk of water damage to paintings. Fire is gaining ground

rapidly. Smoke is building up on the upper floor. Pre-determined attendance is

Released for 3 pumps. Additional resources are not likely to arrive for 10 to 15 minutes.

On arrival the OIC is met by the near hysterical Museum Manager, who tells

him that everybody has been evacuated from the building but the virtually

priceless Picasso paintings are still inside because nobody can get past the fire

on the staircase. The paintings may well already be suffering smoke damage.

January 2013

3

Incident Management – Command and Control

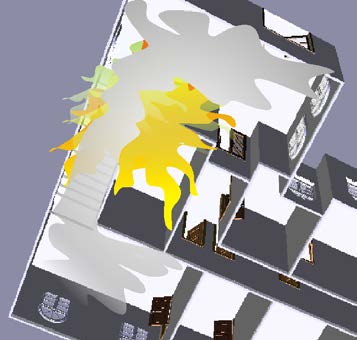

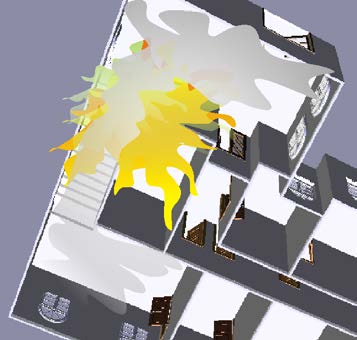

Grou

o n

u d

n F

d l

F oo

o r

o

Fi

F rst F

t l

F oo

o r

o

Picasso

casso

exhi

h bi

b ti

t on

o

n

ga

g llery

Incident Management – Command and Control

Grou

o n

u d

n F

d l

F oo

o r

o

Fi

F rst F

t l

F oo

o r

o

Picasso

casso

exhi

h bi

b ti

t on

o

n

ga

g llery

Act

Stai

t rcase

Stai

t rcase

to

t u

o p

u p

p e

p r

ga

g lleries

En

E tran

r

ce

Information

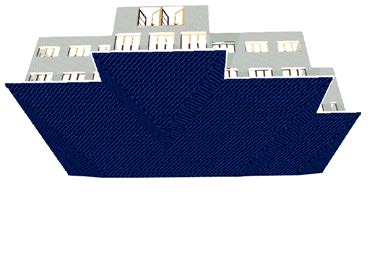

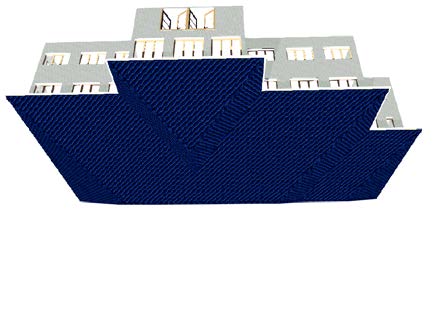

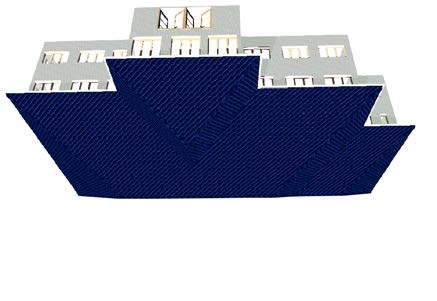

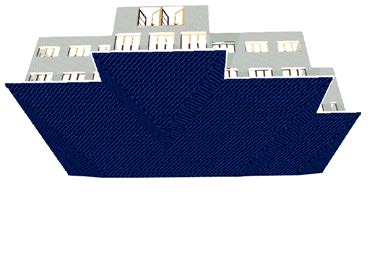

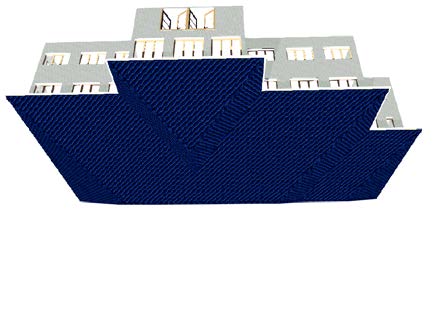

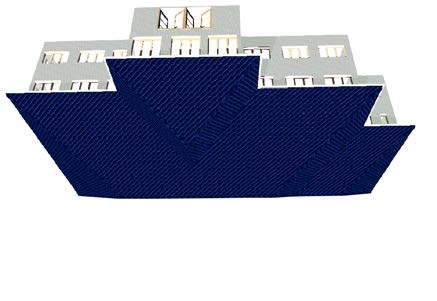

Figure 3.2: Scenario – Fire in arts museum, Ground and First floor views

(Source – NZFS 2006)

3.1.4 Example AIM

This situation probably calls for the (temporary) abandonment of the

operational plan. Instinct directs you to attack the fire immediately, but you

have few resources and must think clearly to prioritise what you really need to

Official

achieve. As a general rule, the AIM can be stated in one sentence:

My AIM is to ‘Rescue’ the Picasso paintings before damage can occur, and

the

then save the remainder of the building.

3.1.5 Example

STRATEGY is usually expressed in non-technical terms.

STRATEGY

My STRATEGY is to use all initially available resources (1 crew) for the snap

rescue of the paintings with all possible speed, then attack fire with all

under

resources as they become available.

3.1.6 Example TACTICS

TACTICS are the methods selected to successfully carry out the STRATEGY.

At this point things usually become more technical, but can still be expressed

simply. Some of the terms discussed here will be further explained later in this

section.

My TACTICS are to:

Commence a search and rescue for the paintings in the first floor Picasso

Released gallery, supported by an interior cut-off.

When sufficient resources are available, commence an interior attack on the

ground floor to knock down the fire. Retreat to exterior attack if required.

Incoming resources to assist according to situation on arrival.

Undertake ventilation and salvage as required.

4

New Zealand Fire Service – National Training

Risk Assessment, Strategy and Tactics

3.1.7 Operational

The Operational TASKING component of incident management is essentially

TASKING

the specific allocation of resources to the various aspects of the TACTICAL

plan.

An operational task includes:

3.1.8

• The person (and crew size) to whom the task is being allocated

• Whomever that person will report to (e.g. Sector Commander)

• The location of the task (may include a grid reference)

Act

• The priority level assigned to the task

• The risk associated with the task

• An indication of when the task was commenced (to indicate when relief

should be implemented).

or

Task

Location

Team Leader No in

Sect

Grid

Crew Tasked at:

Information

3 Search and rescue for Picasso

Top floor rear.

G9/ SFF Smith

2

13:00

paintings and pass out window Access via ladder.

2

to museum staff

3 Interior cut-off to protect

Top floor rear.

G9/ SFF Brown

2

13:02

search and rescue team.

Access via ladder.

2

3 Interior attack to extinguish fire Ground floor.

G9/ SFF James

2

13:03

Official

before extending up the stairs

Access from front

1

entrance.

Ventilation and salvage starting Ground floor

G9/ SFF Smith

2

13:10

the

on the ground floor

1

under

Figure 3.3: The Operational TASKING process (example)

Released

January 2013

5

Incident Management – Command and Control

3.1.9

The tasks are captured regardless of the availability of current resources. The

list reflects what is already deployed, as well as a ‘wish list’ of resources that

are required to deal with the incident. The tasks are prioritised according to

their importance. This method is referred to as ‘planning backwards’. Figure

3.4 describes this method.

With an incident such as the scenario cited above, this would all be done

mentally, and accompanied by verbal instructions, due to the absolute urgency

and relative simplicity of the situation. However, as incidents grow in scale and

complexity there will be an increasing need to document the management Act

process. This is covered in more detail in later sections.

To minimise misunderstanding and confusion, it is important to understand the

terminology being used. In much the same way that the terms ‘dash roll’ and

‘roof flap’ became synonymous with techniques for vehicle extrication, terms

such as ‘Offensive Interior Cut-Off’ are being introduced to general

firefighting for the same reasons.

The process of determining operational tasking will highlight resource

requirements (make up requirements) and the risks associated with each task.

Using this process may in fact (and often does) require more tasking to be

Information

deployed. For example, the risk associated with an offensive Interior Attack on

a building with a high fire loading will require higher supervision,

communication and back-up. Each of these tasks draws down the resources

available.

3.1.10 Devolving

The first arriving officer at a small-scale incident will retain the

Official

responsibility

responsibility for strategy, tactics and most operational decisions until

relieved by a more senior officer from his/her District. However, if the

incident warrants additional resources, the Incident Controller will need

the

to think about delegation of command decision-making once these

arrive.

3.1.11

As the span of control hierarchy grows, the Incident Controller should delegate

as much of the lower level decision-making as possible. This is essential if

under

he/she is to retain overall ‘big picture’ responsibility for strategy and tactics,

leaving the lower level operational decisions to crew leaders.

3.1.12

Consequently, as more resources are deployed, the Incident Controller should

use other officers to share the burden of tactical decision-making. With large-

scale and prolonged incidents he/she should increasingly delegate tactical

decisions, e.g. to FIRE OPS and perhaps to Sector Commanders.

3.1.13 Key concept

The ability to delegate in accordance with incident scale and available

Released resources is a fundamental attribute of effective command.

6

New Zealand Fire Service – National Training

Risk Assessment, Strategy and Tactics

3.1.14 Risk assessment

Risk assessment is the process by which potential strategy and tactics are

– The Safe Person

subjected to analysis to determine whether or not the level of risk they

Concept

represent to operational personnel is acceptable. This is a process that

continues throughout the management of an incident and is consequently

referred to as ‘dynamic,’ i.e. constantly changing.

The process begins immediately on arrival, and at that stage may have to be

performed very rapidly. For example, when arriving at a fire with ‘persons

reported’, the OIC must decide very quickly whether or not to commit

firefighters to a snap rescue. There is a very real tension here between the need

Act

for urgency and the need to ensure the safety of personnel. Making an

appropriate decision under considerable stress is never easy. Officers must be

thoroughly conversant with the principles of the Safe Person Concept, which

will enable them to prioritise clearly in these situations. This is discussed in

greater depth later in Section 3.5.

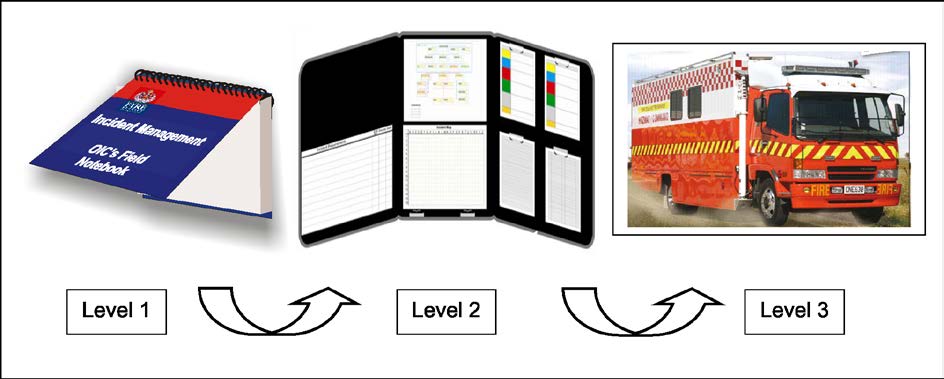

3.2 Incident action planning

Information

3.2.1 Overview – From

Officers and firefighters will respond to most incidents on the basis of

experience

experience – they have seen this kind of incident before and know what is

required to deal with it successfully. Very little planning is required. In these

situations the OIC scans his/her ‘mental filing cabinet’ and when he/she

recognises strong patterns of similarity pulls the file. This is clearly a very

efficient, and perhaps the only means of decision-making when under severe

Official

time pressure. Experience and training combine to fill the filing cabinet.

3.2.2

Decision-making of this kind is referred to as ‘recognition primed decision-

the

making’ (RPDM). It is an entirely natural process and is often referred to as

‘naturalistic decision-making’. Nevertheless it must be balanced by the obvious

merit of giving situations some fresh thinking and avoiding the ‘automatic’

response. For a full explanation of RPDM see Klein (1998).

3.2.3 As a process

The RPDM model tells us that when we are faced with situations we have not

under

encountered before (i.e. there is no appropriate file in the filing cabinet) a more

structured approach is required. This is especially true when the situation is

highly complex and decision-making must take account of many variables. The

OIC should then resort to a decision-making process that is structured to take

account of variables in a disciplined and appropriate order.

Released

January 2013

7

Incident Management – Command and Control

3.2.4

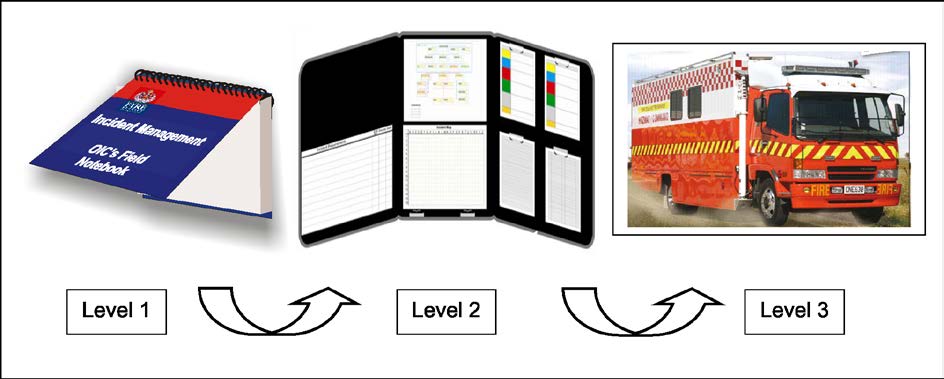

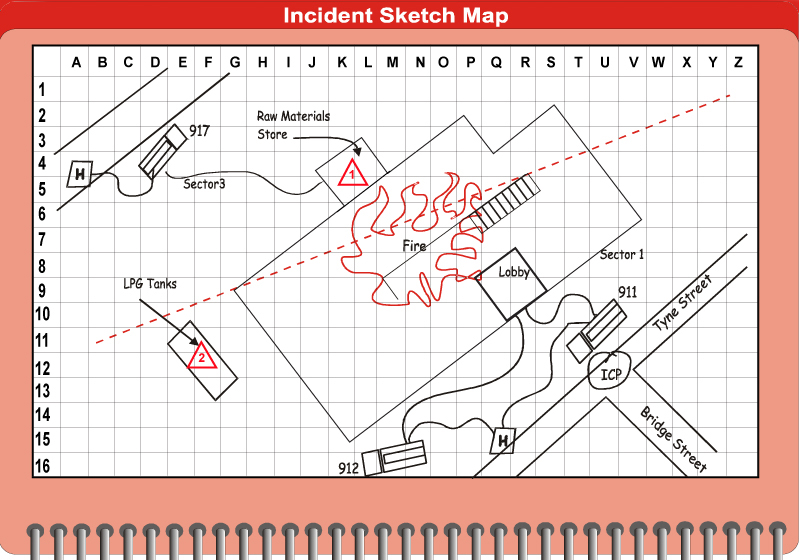

Figure 3.4 illustrates a proven model for arriving at the most effective Incident

Action Plan (AAP/IAP) for NZFS led incidents (this is not necessarily the

process that other agencies will follow). The model consists of a number of

processes that result in outcomes which in turn enable subsequent processes.

Order and structure are essential for success. This does not mean that

individual processes could not be delegated, e.g. in the context of the CIMS

IMT – but the various components would have to be integrated in correct

process order.

3.2.5

Each process within the model is explained further in the following pages.

Act

Information

Official

the

under

Released

8

New Zealand Fire Service – National Training

Risk Assessment, Strategy and Tactics

Process

Size Up

- 360 observation

- information gathering

- hazard identification

- potential for escalation?

Risk Assessment, Strategy and Tactics

Process

Size Up

- 360 observation

- information gathering

- hazard identification

- potential for escalation?

Act

Outcome

Essential data for developing the

plan.

Process

Plan backwards. What resources

are needed to deal with the full

potential of this incident?

w

s

s

ie

Outcome

Strategy development and tactical

v

e

Information

c

plan.

re

ro

s

p

u

o

ic

Process

Translate to Make-Up requirement.

u

m

- What does this mean?

a

- Greater alarm level + specials?

tin

Official

n

n

- Command assistance / SME’s

y

o

C

- d

the

Outcome

Resource plan.

under

Process

Priortise actions and tasks.

- Refer to RECEO

- Life, Property, Environmental

Outcome

Fire Service Action Plan.

Figure 3.4: Structured process for fire incident action planning

(Source NZFS 2006)

Released

Figure 3.4: AAP/IAP Planning Model

January 2013

9

Incident Management – Command and Control

3.2.6 NZFS Agency

Incident Management – Command and Control

3.2.6 NZFS Agency

‘Size-up’ is an assessment, usually by the OIC, of the various factors that

Action Plan (AAP) –

impact upon the incident in question. This involves, as far as possible, an

Size-up

assessment of the whole incident site. Failure to grasp the whole situation may

lead to strategic or tactical errors (or indeed to pursuing an inappropriate aim).

The need for urgent action (e.g. search and rescue) will often be a legitimate

but significant distraction from the wider tasks of size-up. Consequently, the

OIC should delegate as many immediate actions as possible to his/her

firefighters, within the limits of their competence. For example, a size-up of a

significant fire at a tank farm may reveal one person needing rescue, but also

Act

the potential for major explosions. With ensuing widespread damage and

injury, the Incident Controller must prioritise where his/her attention should be

primarily focussed. The rescue task must be delegated to allow the incident

controller to attend to the bigger picture.

Size Up

- 360 observation

- information gathering

- hazard identification

- potential for escalation?

Information

Information gatheri ng through size-up must attempt to assess the whole

incident site. Failure

to do this may lead to ineffective planning and response.

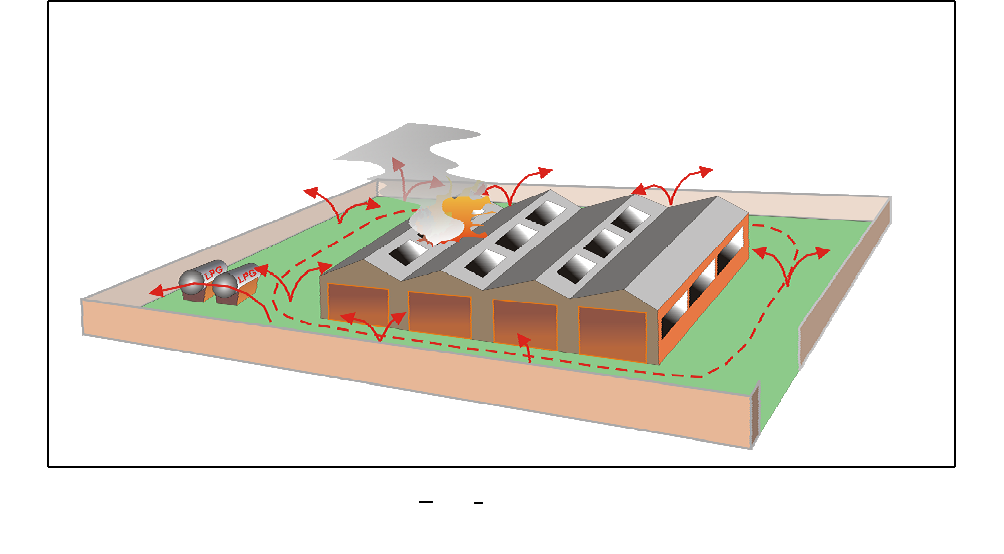

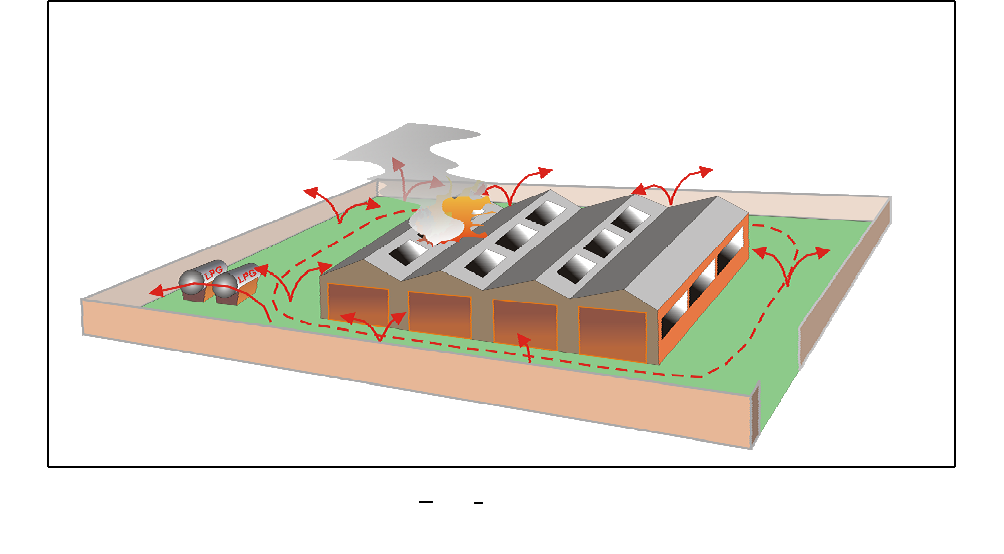

3.2.7 360° observation

Whenever possible, officers should always conduct a 360º assessment (i.e. do a

complete circuit around the incident, or at least as much as possible).

Alternatively, obtain information from others who are better positioned. Figure

Official

3.5 below illustrates the 360° principle.

the

under

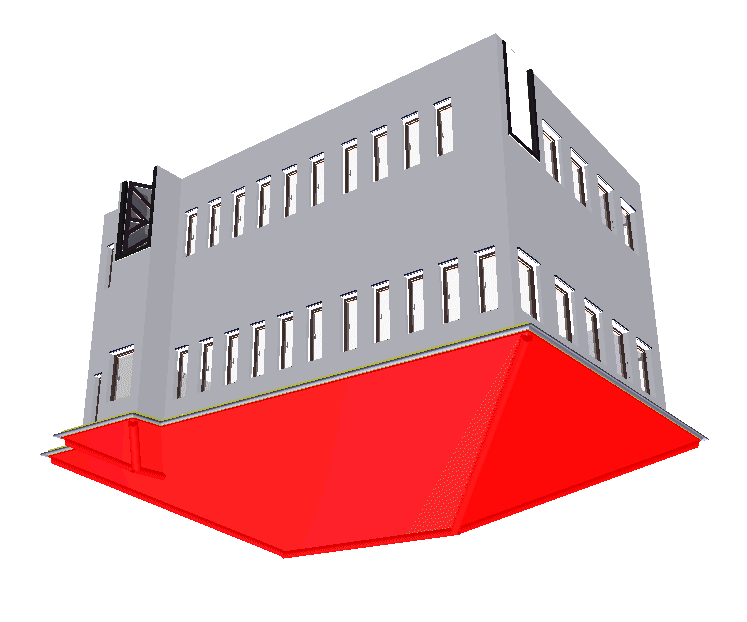

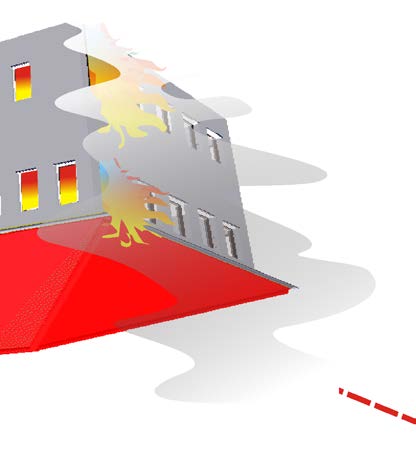

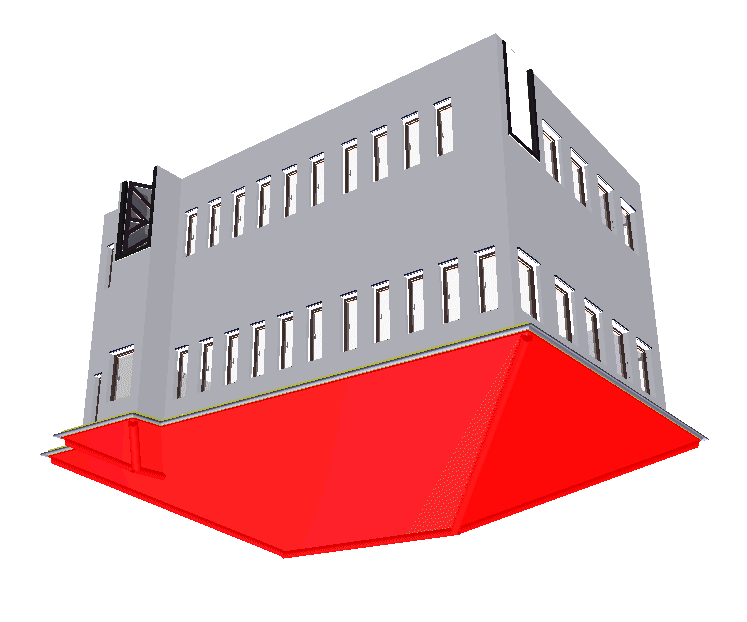

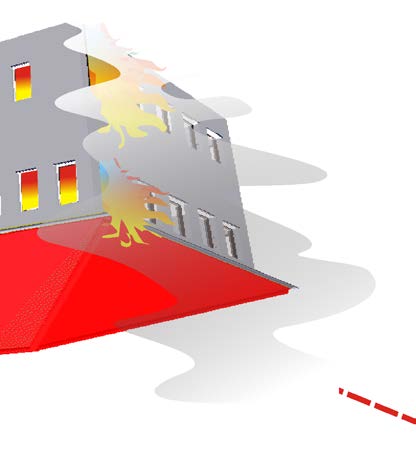

Figure 3.5: 360° assessment

(Source – NZFS 2006)

Released

10

New Zealand Fire Service – National Training

Risk Assessment, Strategy and Tactics

3.2.8 Information

Officers must realise that the key to effective decisions on the incident ground

gathering

is in seeking and processing useful information. Obtaining this information is

never straightforward, but is much easier with an understanding of what

information is needed.

This requires an understanding of ‘access opportunities’ – windows of

opportunity through which information can and should be gathered. This

process continues throughout the incident and ensures that previously gathered

information is validated and updated as progress is made.

3.2.9 BSAHF

Act

BSAHF is a memory aid to read a fire. It stands for:

•

Building

•

Smoke

•

Air track

•

Heat

•

Flame

3.2.10 BSAHF – Building The type, age and purpose of a building can inform firefighters about the type

Information

of fire that they could encounter inside.

3.2.11 BSAHF – Smoke

Smoke is a useful indicator of the intensity of the fire as well as what type of

substance is on fire

3.2.12 BSAHF – Air Track Read the air track with the neutral plane. A sudden change in the air track can

be a sign of flashover. Official

Lazy flowing air tracks show good oxygen supply and erratic air tracks show a

fire searching for oxygen.

the

No air track shows a fire in decay or a contained fire burning its available

oxygen.

3.2.13 BSAHF – Heat

Heat can show the stage and fire intensity as well as the type of fuel.

under

3.2.14 BSAHF – Flame

Lengthening flame signals gases approaching their LFL (lower flammable

limit).

Red flame is a sign of energy-rich fuels or fuels burning close to their UFLs

(upper flammable limit). Yellow flame is seen with normal-energy fuels or

fuels burning close to their LFLs.

Released

January 2013

11

Incident Management – Command and Control

3.2.15 Access

Information relevant to any given incident may be gathered from a wide range

opportunities

of sources, to make risk assessments, strategies and tactical options for that or

similar locations. Useful (perhaps vital) information can be gathered:

• Pre-incident – through risk planning, topographical knowledge, liaison

with key personnel at the potential incident ground, local emergency

plans, site visits etc.

• Pre-incident – through understanding of NZFS policies and Operational

Instructions

• En-route – through contact with the Comcen, other appliances, other

agencies etc.

Act

• On the incident ground – through effective 360° assessment

• On the incident ground – from bystanders, wardens, casualties,

evacuees, or employees fleeing the building, other rescue service

personnel etc.

• On the incident ground – through sensory data – i.e. what you and

others can see, hear, smell, or feel. For example, there may be closed

curtains, shoes at the front door, the smell of petrol, lights turned on, a

car in the garage, establishment of interior building layout from outside

(360° assessment), signage (e.g. HazChem)

Information

• Post-incident – through lessons learned from operational debrief,

analysis and reporting.

3.2.16 Hazard

When gathering information, either directly or through other personnel, the

identification

identification of actual and potential hazards must be at the forefront of the

Official

OIC’s mind. Failure to identify a hazard may result in inadequate risk

assessment and thus place firefighters or other attending personnel in danger.

the

The presence of hazards does not necessarily impede operations, but if they are

significant they must be eliminated, isolated or minimised. The logging (or

verbal notification) of the hazard and the selected mitigation strategy should be

communicated to staff at the incident and captured in the Hazard Register

section of the AAP.

under

Released

12

New Zealand Fire Service – National Training

Risk Assessment, Strategy and Tactics

3.2.17 Potential for

Risk Assessment, Strategy and Tactics

3.2.17 Potential for

Whenever possible, the OIC should aim to move from being reactive

escalation

(responding to the incident as it develops) to being proactive (predicting how

the incident will develop and bringing in sufficient resources to deal with that

potential).

This can be difficult to do when the OIC is also dealing with immediate actions

– but shows again the obvious merits of effective delegation to create ‘thinking

space’. The decision process can be assisted by simple questions such as:

• ‘What could make this situation get worse?’

•

Act

‘How bad could it get?’

• ‘What are the implications if it gets to that stage?’

There is obvious wisdom in recognising Murphy’s well known ‘law,’ i.e. ‘If it

could go wrong, it most likely will go wrong’. It seems pessimistic, but it is in

fact a responsible and professional attitude to see possible developments of the

situation and to be prepared for them if they were to eventuate.

3.2.18 Planning

Once the potential for escalation has been assessed the obvious questions are:

backwards

• ‘Are my current resources sufficient to contain it if it does get that

Information

bad?’

• ‘Are the resources that I am tasking going to need ‘rolling over’ or

replacing before the task is completed?’ This will need to be factored

into the ‘make up’ decision

• ‘What additional resources would I need to deal with the full potential

Official

of the incident?’

• ‘If I can get them how and when would I best use them?’

• ‘To successfully conclude this incident, I will need to…’

the

Of course there may be limitations on available additional resources. There is

also a natural tendency to resist calling for more resources just in case it turns

out that they are not needed. Nevertheless, turning resources around is always

preferable to watching property burn down unnecessarily.

under

The Operational Tasking table shown in Figure 3.3 indicates a method that can

be used to capture the ‘planning backwards’ technique, while also capturing the

crew numbers and therefore providing information to determine the appropriate

alarm level.

Note: Refer to Region Greater Alarm system.

Plan backwards. What resources

are needed to deal with the full

Released

potential of this incident?

January 2013

13

Incident Management – Command and Control

3.2.19 Translate to make-

Incident Management – Command and Control

3.2.19 Translate to make- Having identified the resources required to manage the full escalation potential

up

of the incident, these need to be translated into make-up terms and the

requirement communicated immediately to the Comcen.

Fundamentally the questions to be answered are:

• ‘What level of alarm do I need?’

• ‘What if any, special appliances do I need?’

• ‘What, additional command support do I need?’

Act

• ‘What, if any, specialist expertise do I need?’

Translate to Make-Up requirement.

- What does this mean?

- Alarm + specials?

- Command assistance / SME’s

3.2.20 Prioritise actions

Successful deci sion-making will depend on the officer’s ability to match what

and tasks

he/she already k

nows (pre-incident information) with what he/she can find out

on the incident g

round (size-up) and then to prioritise actions accordingly.

Information

Other personne l, e.g. fire safety, should provide much of the pre-incident

information, but

incident ground size-up will be entirely the responsibility of

the first arriving

officer. It is essential then that he/she has a thorough

understanding of

what constitutes effective prioritisation. The NZFS model for

this process is R

ECEO.

Official

Priortise actions and tasks.

- Refer to RECEO

- Life, Property, Environmental

the

under

Released

14

New Zealand Fire Service – National Training

Risk Assessment, Strategy and Tactics

3.2.21 RECEO

RECEO is a mnemonic intended to assist prioritisation of tasks. It is expanded

as follows:

•

R - Risk to life? Search and rescue required?

•

E - Exposures? Exterior exposure protection required?

•

C - Containment? Interior/exterior cut-off required?

•

E - Extinguishment? Interior/exterior attack?

•

O - Overhaul? Ventilation/damping down etc.

Act

3.2.22

Although these considerations imply a linear thinking process, it is important

to understand that simultaneity = speed, i.e. officers should aim to process

information on a multi-task basis rather than an absolute focus on single

aspects. Once again this requires ‘thinking space’ which can only be gained

through effective delegation.

3.2.23

RECE

O should be regarded as a dynamic process because the progress of an

incident can never be entirely predicted. Priorities may need to be adjusted, and

the only way to do this effectively is to maintain information gathering.

Information

The notes below expand on these key information areas and detail the kind of

information that should be sought under the broad headings above.

3.2.24 RECEO – Risk to

This is the paramount consideration. The protection and preservation of the life

life

of firefighters and of the public must be uppermost in the mind at all times.

When ‘scanning’ the incident ground, officers should gather information both

Official

as it presents itself, and also in a more structured way. Information should be

sought in relation to:

the

1. Immediacy of any threat – how urgently must you act?

2. Who is at risk/under threat?

• How many?

under

• Age(s)?

• Physical/psychological condition?

3. Is rescue required?

• For how many?

• From where?

•

Released

What threats does the rescue environment offer to fire crews?

• To where? Is there an obvious area to which those rescued can be

safely removed and attended to while awaiting evacuation?

•

Are there obvious priority cases?

• Do I need to carry out a search? Can I be sure that there are no persons

unaccounted for?

January 2013

15

Incident Management – Command and Control

• What threats does the rescue environment offer to my crew(s)?

• State of building?

• Particular hazards e.g. electricity, gas, flooding etc.

• Stability of the rescue environment? e.g. possible collapse, spread of

fire and smoke.

•

Resources/scale of incident? Do I have the resources (crew and

equipment) to do what is needed here? Do I call for assistance?

3.2.25 RECEO –

It is important to realise that any incident will raise the question of exposures.

Act

Exposures

Simply defined, an exposure is any property or facility whose proximity to the

fire or hazard places them in danger if the fire or hazard should develop.

Whether acting in offensive or defensive tactical mode, officers must take

adequate steps to protect exposures whenever possible.

Officers should seek information on the following:

• Likelihood of the fire/hazard escalating?

• Likely pattern or direction of fire/hazard development?

Information

• Aggravating factors e.g. wind strength and direction, presence of

volatile fuels etc.

• Distances between exposures and the fire/hazard?

• Structure type, and current use?

• Human content of exposed buildings e.g. hospital wards etc.

Official

• ‘Value’ of contents of exposed buildings e.g. museums, libraries, art

galleries etc.

the

3.2.26 RECEO –

Linked directly to the identification of exposures, containment is generally

Containment

defined as any action taken to prevent a fire or hazard from spreading to

previously unaffected areas. Typical containment tactics would include:

• Extinguishing the fire/eliminating, isolating or minimising the hazard

under

• Removing fuel from the likely path of the fire

• Redirecting the fire

• Creating fire-breaks/cut-offs

• Offensive attack to push fire back into previously burnt areas

• Shielding with water curtains or jets

• Shielding with water soaked materials.

Released

16

New Zealand Fire Service – National Training

Risk Assessment, Strategy and Tactics

3.2.27 RECEO –

Whether attacking the fire offensively, or seeking to contain it via more passive

Extinguishment

tactics, the eventual aim will still be to extinguish it. This is not a simple matter

and will involve the officer and his/her crew in a decision-making process

based upon a wide range of factors. The main factors to be considered are:

• Size and intensity of the fire

• Type of fuel(s) involved

• Amount of fuel involved or potentially involved

• Distribution of the fuel(s) within the fire environment

Act

• Availability of required extinguishing medium

• Location of the fire – how easy is it to get at?

• Availability of required equipment

• Availability of firefighting personnel

• The environment and exposures – how critical is it to extinguish rather

than contain? This question might well give different answers for high-

density urban areas compared to unpopulated rural areas

• General access – can you maintain sufficient re-supply of equipment

Information

and materials through the access routes?

3.2.28 RECEO –

Overhaul is the latter stage of incident management which ensures that all parts

Overhaul

of the fire are fully and finally extinguished. Typical overhaul tactics will

involve:

• Searching for and fully extinguishing any remaining isolated pockets of

Official

fire

• Turning over and spreading out remaining debris looking for hot spots

the

•

Opening up walls and ceiling spaces to check for hot spots

• Use of the thermal imaging camera (TIC).

At this stage it is important to remember that any subsequent fire investigation

will need to examine the site for evidence. Consequently, as far as possible, it

under

is important to restrict the use of jets in favour of spray or foam application in

an effort to preserve evidence in place.

Released

January 2013

17

Incident Management – Command and Control

3.2.29 AAP process at

Typically, these smaller incidents are managed by the senior officer in

1st and 2nd alarm levels attendance and require little or no delegation. Generally, there is no

requirement for a formal (written) action plan, but the AAP process should be

followed mentally, in a simpler form, to ensure a successful outcome.

The process consists of three significant steps:

• Size-up

• Action planning

• Make-up.

Act

Action planning

To determine strategy, tactics and related operational tasking. This also

involves the deployment of resources.

Make-up

Make-up of any additional resources required to manage the incident to a

successful conclusion. This decision evolves from an effective size-up.

Note: the make-up requirement results from the operational tasking process.

3.2.30 Example scenario

Information

– Situation

• An intense kitchen fire on the ground floor of a substantial two-storey

private dwelling

• Persons reported

• The building is located in a reticulated residential area

• Pre-determined attendance is for two pumps.

Official

3.2.30.1 Size-up

The main conclusions are:

• Fire will spread and may threaten missing persons and the stairway

the

• Fire will cause property damage both vertically and horizontally

• No exposures

• Hazards are stairway and electrical.

under

3.2.30.2 STRATEGY

Rescue missing persons and minimise property damage.

3.2.30.3 TACTICS

• Search and rescue area of greatest risk first and remove/rescue persons

reported

• Administer primary first aid

• Establish an adequate water supply and position interior attack

deliveries to contain and extinguish fire

Released • Complete ventilation and salvage.

3.2.30.4 Operational

Requirements are detailed in Figure 3.6.

TASKING

18

New Zealand Fire Service – National Training

Risk Assessment, Strategy and Tactics

Task

Location

Team

No in

Sector

Grid

Leader

Crew Tasked at:

GND Search and rescue (SARU) Gnd floor rear

G3/1 SFF White

2

13:00

TOP Search and rescue (SARU) Top floor rear

G9/2 SFF White

2

13:00

GND Interior attack

Gnd floor stairwell side C4/1 SFF Green

2

13:00

GND Interior attack

Gnd floor rear

G9/1 SFF Black

2

13:00 Act

Pump Op

ECO

Safety Officer

BA emergency crew

Incident control er

Sector commanders

Figure 3.6: Example of operational tasking record for typical second alarm incident

Information

Total requirement = 16

Available on first alarm = 8

3.2.30.5 Make-up

In this example there is an immediate shortfall of eight firefighters. Therefore

Official

an additional two pumps are required. The priority is to transmit a 2nd alarm.

3.2.30.6 Agency Action

The need at this stage is to prioritise those tasks identified and deploy from the

Plan

resources immediately available. For example:

the

• Pump operator/water supply/Entry Control Officer

• Team 1 – firefighting to protect stairway – containment

• Team 2 – search and rescue. Ground floor, closest to the fire and

working outwards

under

• Team 3 – search and rescue. First floor working above fire outwards.

Note: safe egress to be assured at all times.

Note that at any time during this incident, the Incident Controller is working

within a plan, and is able to minimise risk and to hand over effectively if

required. Naturally, the plan needs to be continually reviewed. This process

should be used for all incident types, expanding to a written version when

command delegations are necessary.

Released

January 2013

19

Incident Management – Command and Control

3.3 Selecting STRATEGY: key principles

3.3.1

Selecting an appropriate STRATEGY is critical, since TACTICS and

operations flow inevitably from that decision. Even if the AIM is clear there

may be (indeed usually are) several possible strategies that could be employed

to achieve it.

3.3.2

For example, if we refer to the simple Museum fire scenario we looked at Act

earlier, a clear AIM has emerged – to save the immensely valuable Picasso

paintings. There are however at least two plausible strategies to achieve this

aim:

1. Extinguish the fire before it can reach the gallery where the paintings are

displayed, or

2. Remove the paintings before the fire can reach them.

3.3.3

In this scenario the OIC chose the second strategy because of the immediate

risk of smoke damage. If the first strategy was adopted, the paintings might

suffer considerable damage even if the fire did not reach them.

Information

3.3.4 Consideration of

This simple scenario illustrates the need to consider all the factors that impact

impact factors

on the situation. This is no easy matter when subjected to the pressure for

action that is inevitable on the incident ground.

It is at this stage that automatic reliance on previous experience could be a

Official

hindrance – for example, the OIC reacts to pressure by doing the apparently

obvious and in the process misses a critical factor.

3.3.5 Example

Remember that ‘there is always more than one way to get a cat out of a tree!’:

the

• Retrieval by ladder

• High pressure delivery + net

• Shake the tree + net

•

under

Pole-saw the branch + net

• Wait for it to get sufficiently hungry to come down of its own accord.

Released

20

New Zealand Fire Service – National Training

Risk Assessment, Strategy and Tactics

3.3.6

Which STRATEGY is finally adopted must depend on a wide range of impact

factors, including:

• Access to the tree

• Working space around the tree

• Location of the cat

• Tools and resources available

•

Attitude and anxiety level of the owner

Act

• Attitude and anxiety level of the cat.

3.3.7

The most suitable STRATEGY emerges very quickly from the interaction of

the impact factors. The principle here is to take enough time to ensure that the

critical factors are identified early in size-up.

3.3.8 The CIMS context

With a large inter-agency response, the designated Planning and Intelligence

Manager/Section, assisted by the other members of the Incident Management

Team (IMT), will conduct the selection and continual review of appropriate

strategy. The Incident Controller would then approve any revisions to the

Information

strategy. However, the complexity of the incident may increase to the point

where the issue of the fire itself becomes just another aspect of the overall

situation. In this case the OIC Fire will be tasked with dealing with the fire

situation, while the Incident Controller coordinates the total incident with all of

the other agencies present.

3.3.9

Official

Consequently, decision-making in these circumstances is a team effort. The

Incident Controller needs to manage the thinking of others, and this can only be

done effectively by using a commonly understood process. When acting as

Incident Controller, NZFS officers will find that using the CIMS process at the

the

higher level and delegating the NZFSCS incident action planning process

(shown in Figure 3.4) to another officer will enable the Incident Controller to

manage team planning in a structured and inclusive fashion.

3.3.10

Within the appreciation process there is of course room for individuals to

contribute Recognition Primed Decision Making (RPMD) (refer to 3.2.2) ideas

under

arising out of their personal experience and perception. These become part of

the identification of possible courses of action.

Released

January 2013

21

Incident Management – Command and Control

3.4 Selecting tactics and tactical modes

3.4.1 Overview

When related to firefighting alone, the typical tasks demanded of firefighting

fall into common categories. These categories have traditionally only been

referred to informally on an incident ground.

In much the same manner that descriptive terms such as ‘Dash Roll’ or

‘Inverted Roof Flap’ have revolutionised motor vehicle extrication

Act

management, similar terms can be adopted for classical fire attack tactics. The

notes below add some formality and structure to these otherwise informal

terms.

It is intended that these terms become key words in the vocabulary of officers

and firefighters resulting in effective and unambiguous directions – ‘I know

exactly what you mean when you say……...’.

The tactical options icons are also included to emphasise, in a graphic manner,

the intention of the tactics. These same icons are used for the incident plan in

the Command and Control Pack to denote what tactical option is being

Information

deployed at different locations at the incident.

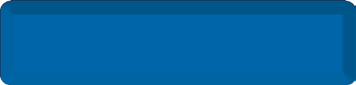

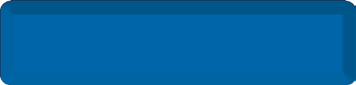

The colour coding on the icons (page 23 – 26) indicates typical risk of the

activity, e.g. an offensive Interior Attack is at the red/orange end of the scale

indicating a medium to high risk, while some other activities are at the

orange/green end of the scale indicating a medium to low risk. This risk

Official

appreciation can then be applied accurately and effectively to the safe person

concept. (Refer to Figure 3.8.)

the

3.4.2 Tactical options

As the term implies, ‘offensive’ mode involves a concerted and aggressive

Definitions – Offensive

attack on the fire (or part of the fire) with a view of achieving control,

mode

knockdown and extinguishment. The OIC would adopt offensive mode if

he/she believes that current resources will prove adequate to attack the fire and

the incident status will allow this to be conducted without undue risk.

under

The prime considerations for the Incident Controller are the need to pursue a

goal offensively or aggressively and the ensuing risk that this entails. In other

words, an offensive attack implies a heightened risk, which therefore requires a

heightened consideration of supervision, communication and support.

The most offensive response to a structure fire situation is to enter the building,

seek out the source of the fire and seek to extinguish it by aggressive and

concerted direct firefighting techniques (offensive Interior Attack).

Released The decision to opt for offensive or defensive tactics will clearly be related to

the aim and selected strategy. The OIC must be clear about what it is he/she is

trying to achieve, the best method of achieving it, and whether that method

warrants an offensive or defensive approach.

22

New Zealand Fire Service – National Training

Risk Assessment, Strategy and Tactics

3.4.3 Definition –

There will be occasions where firefighters may need to enter a building that is

Defensive mode

well involved in fire but cannot do so for more than short periods, or perhaps

do not intend to extinguish the fire as a priority. For example:

• Rescue situations – where a firefighter will protect a rescue team

• To hold ground while awaiting sufficient resources to mount a more

offensive attack

• To protect particularly valuable parts of a property

• To hold the fire at bay long enough to remove valuable or hazardous

Act

substances.

In these circumstances the general mode of working is ‘defensive’ in the sense

that the objective is not (at this time) to overcome the fire.

Assuming that a lower level of aggression will achieve the aim, the OIC may

decide that an offensive attack would expose firefighters to unacceptable risk,

and therefore he/she may opt to attack the fire using a more defensive mode.

The Incident Controller in this case has accepted that safety of the crew is

paramount and they are not to expose themselves to a risk of injury, perhaps

because the objective is not worth a heightened risk to the crew. (Consider the

Information

Safe Person Concept.)

This may involve retreating and changing the fundamental tactics from using

an interior attack to an exterior attack and therefore directing jets through

windows and doors, or perhaps removing parts of the external structure in

order to allow greater volumes of water to be applied. A defensive mode is

therefore synonymous with a more cautious approach to risk.

Official

The above discussion does not suggest that the terms ‘offensive’ and

‘defensive’ must be related to the overall incident tactics. In fact, many tactical

the

options and the associated modes may be applied at the same incident. Having

stated that however, it is appropriate that a Sector Commander or OIC can

communicate that an incident is being managed in a predominately offensive or

defensive mode.

Given the rising level of risk that would normally be associated with the move

under

from defensive to offensive tactics, we might think of the tactical options as if

they were a continuum from high risk to low risk. Clearly, risk assessment will

need to be increasingly acute as the OIC moves toward a decision for offensive

interior attack. This concept is illustrated at Figure 3.7 below.

Released

January 2013

23

Incident Management – Command and Control

3.4.4 Interior attack

Interior attack means:

Committing firefighters to entering the building/structure in order to attack the

fire. The clear intent is to achieve rapid knockdown and extinguishment.

Interior Attack

Act

3.4.5 Exterior attack

Exterior attack means:

Attacking the fire from outside the building/structure e.g. through windows,

doors etc. The clear int ent is to achieve rapid knockdown and extinguishment

Information

when an interior attack is not an acceptable option.

Exterior Attack

Official

the

under

3.4.6 Interior cut-off

Interior cut-off mean

s:

Committing firefighte

rs to entering the building/structure in order to contain

the fire within a specific area. This may be done to prevent fire spread, to

protect search and rescue teams, or perhaps to enable the removal of valuables.

Interior Cut-Off

Released

24

New Zealand Fire Service – National Training

Risk Assessment, Strategy and Tactics

3.4.7 Exterior cut-off

Exterior cut-off means:

Preventing interior fire spread from outside the building/structure by the use of

jets through windows, doors, forced entry apertures etc.

Exterior Cut-Off

Act

Information

3.4.8 Interior exposure

Interior exposure protection means:

protection

Committing firefighters to entering the building/structure in order to protect

assets/property close to the fire itself, as an example or to cool a fixed LPG

tank, which is at risk. This would often be associated with interior cut-off or

interior attack.

Official

Interior Exposure

Protection

the

under

Released

January 2013

25

Incident Management – Command and Control

3.4.10 Exterior exposure Exterior exposure protection means:

protection

The protection of assets or property outside the building/structure but close

enough to be at risk.

Exterior Exposure

Protection

Act

3.4.11 Search and rescue Search and rescue (uns

upported) means: Information

(unsupported and

supported)

Committing a rescue te

am to the interior of a building/structure without the

protection of an additi

onal team tasked to protect them while the rescue is

carried out.

Search and Rescue (su

pported) means:

Official

Providing an additiona

l team tasked to protect firefighters carrying out the

rescue or the search te

am providing their own fire protection.

the

Search & Rescue

Unsupported/Supported

under

SARU

SARS

Released

26

New Z ealand Fire Service – National Training

Risk Assessment, Strategy and Tactics

3.4.12

Ventilation means:

Ventilation/evacuation

The removal of gases, noxious fumes etc. in order to prevent re-ignition and to

render the atmosphere safe for working without breathing apparatus, e.g. for

salvage work.

Evacuation means:

The controlled removal of people from the fire-affected building/danger area in

order to ensure their safety and to allow operations to proceed.

Act

Ventilation/Evacuation

V

E

Information

Official

the

under

Released

January 2013

27

Incident Management – Command and Control

3.4.13 Tactical mode

To emphasise the importance of a task to the overall strategy, the OIC Fire can

select and communicate the most appropriate tactical mode. This indicates the

boundaries of how the tactical options will be deployed. These boundaries are

determined by the value of what is at risk and its relationship to the risk

imposed on the firefighters deploying the tactics. In other words, the OIC can

communicate to the crew officer, in very simple and unambiguous terms, the

level of risk to which he/she should expose the crew, on the basis of the value

at risk. (Refer to the Safe Person Concept discussed later in this section.)

From the previous notes on tactics, the OIC Fire can determine that a goal

Act

warrants a tactical option to be pursued in an offensive manner, and therefore

combines the tactics and the mode together, e.g. an offensive Interior Cut-off.

The power of using defined terms such as these enhances communication and

in fact distils important concepts and guidelines into unambiguous

terminology. This also introduces a hierarchy of risk associated with different

tactics when considered along with the mode of deployment. In the example

above the OIC could categorise the task as being of high risk which may

prompt a control measure to minimise that risk (such as providing a higher

level of supervision).

The most important consideration is always whether the tactical option should

Information

be tackled by offensive or defensive modes, or perhaps some combination of

both at different locations within the same incident. Incidents are of course

never entirely predictable in the way they unfold, and the OIC may need to

adapt or entirely change his/her attack modes or even tactics to suit the

changing conditions. The OIC may insist on a defensive mode when an

offensive mode could push the fire onto another crew operating nearby, or

when the value of the exposure is not worth the risk to the firefighters making

Official

entry.

3.4.14 Responsibility for While the responsibility to dictate the Tactical Option and the mode that the

the

determining tactics

option is deployed remains firmly with the OIC, Sector Commanders, Crew

Officers or Safety Officers (Fire) can use their experience and judgement to

order a change in tactical approach only when the safety of firefighters is

compromised.

Any spontaneous changes must be immediately communicated to the OIC. i.e.

under

‘I am unable to maintain an offensive mode and am now in defensive mode’ or

‘I am retreating and commencing an offensive Exterior Attack’. Failure to do

so may result in increased risk in other sectors or to other crews even in the

same sector. It is imperative that whenever possible, proposed changes should

be discussed with the appropriate commander before any unilateral change of

tactical mode or option is implemented.

The OIC may then choose to reinforce the position with more resources or

accept the resultant reduction in progress at that point. (Refer to the SHURTS

Released Sector Commander SitRep format for terminology relating to this and the

progress at the point deployed.)

28

New Zealand Fire Service – National Training

Risk Assessment, Strategy and Tactics

3.4.15 ‘Continuum of

Risk Assessment, Strategy and Tactics

3.4.15 ‘Continuum of

Given the rising level of risk (likelihood and consequence) that would normally

risk’

be associated with the move from defensive to offensive tactics, we must think

of the tactical options as closely aligned to the deployment of any control

measures to mitigate the risk. Clearly, the balancing of risk and the mitigating

control measure will need to be increasingly acute as the OIC moves toward a

decision for offensive interior attack. This concept is illustrated at Figure 3.7

below.

Act

Information

Official

the

Figure 3.7: Tactical ‘Risk Continuum’

(Source – NZFS 2006)

under

The last step in finalising tactics is to think carefully about the level of risk to

which firefighters will be exposed because of their deployment.

Released

January 2013

29

Incident Management – Command and Control

3.5 Safe Person Concept

3.5.1 Safe Person

The Safe Person Concept (SPC) is about thinking and acting safely. In your

Concept

role as a firefighter, you will be faced with hazards that could cause serious

harm or injury. You will need to be aware of potential hazards and make

decisions that will keep you, your crew, and the public safe. The SPC will help

you to do this successfully.

Act

The SPC involves all the things needed to do the job safely. This includes:

• maintaining ‘situational awareness’ (knowing what is going on around

you)

• being aware of hazards

• making decisions to reduce risks

• making decisions about what risks are acceptable

• using Dynamic Risk Assessment (DRA)

Information

• being prepared for unexpected changes

• following operational procedures

• taking direction from your officer

• being trained to do the tasks assigned to you

Official

• using personal protective equipment (PPE)

• using the right equipment for the tasks you perform.

the

The SPC underpins everything you do in the NZFS. It is the principle of

‘safety first’.

under

Released

30

New Zealand Fire Service – National Training

Risk Assessment, Strategy and Tactics

3.5.2 Safe Person

Concept overview

The principle of ‘Safety

First’

PEOPLE

HEALTH and SAFETY

Knowledge

Hazard identification

Skill

Risk assessment

Attitude

Hazard controls

Act

Training

Risk management

Responsibilities

Dynamic Risk

Assessment

PROCEDURES

EQUIPMENT /

Planning

RESOURCES

Risk analysis

Integrated PPE

Tactics/tasks

Firefighters/crews

Operational instructions

The right tools for the job

Command and Control

Likelihood/consequence

assessment

Information

Official

Figure 3.8: Safe Person Concept overview

the

3.5.3 Levels of

responsibility

At an incident, there will always be an Officer in Charge (OIC). The OIC will

decide on the right people for each task, the procedures to follow, and so on.

They will do as much risk management planning as is practical to make sure

the job is as safe as possible for you and your crew.

under

However, it is important that you don’t ever just blindly follow instructions.

Sometimes you may see a hazard your OIC missed, or you may identify a new

hazard when your OIC is not nearby. Using the SPC, you will make the

decision on how to proceed, so that you can do the job as safely as possible. At

times, you may decide not to continue with a task if it is too unsafe to do so.

You are responsible for safety at three levels:

Released

Task level

doing the job safely

Team level

helping to ensure the safety of those you work with

Individual level

ensuring personal safety, e.g., wearing correct PPE

Officer level responsibilities are also set out below.

January 2013

31

Incident Management – Command and Control

3.5.4 Task level

You need to ask yourself:

• what does it take to do this task safely?

• have I been trained to do it (e.g., procedures/skills)?

• what equipment will I need (e.g., correct PPE, breaking and entry tools,

fire extinguisher, hose deliveries)?

• do I need help with the task (e.g., when lifting heavy equipment)? Act

Be careful not to be totally task-focused, because this creates the possibility of

individual or team safety being ignored because of the drive to get the job

done.

3.5.5 Team level

The team approach to incidents is the basis of how NZFS operates. Each crew

is a team, with each member of the team having a role to play. There will be a

variety of skills and experience in the team, and the OIC will take these into

account when allocating tasks.

Members of a team must develop a high degree of trust in each other and must

also take responsibility for watching out for each other.

Information

3.5.6 Individual level

Your responsibilities are to:

• be aware of hazards

• assess the risk for all tasks you perform

Official

• adapt to changing circumstances

the

• use training do the job safely

• work with equipment safely

• work within NZFS systems and procedures

under

• be an effective team member

• identify when you are not trained/skilled for a particular task

• be vigilant regarding personal, team, and public safety.

To be safe, individuals must accept responsibility for safety at all levels.

An individual who takes needless risks endangers not only themselves but also

Released their crew, who may have to step in to rescue them. This may also affect the

ability of the team to complete the task (by drawing resources away from that

task).

32

New Zealand Fire Service – National Training

Risk Assessment, Strategy and Tactics

3.5.7 Officer level

The OIC is responsible for risk assessment and risk management at an incident.

The OIC will rely on a number of tools to help manage risks, such as:

• operational instructions

• Command and Control (including the overall strategy, tactics and

tasking)

• information provided by the crew

•

Act

experience

• training

• available resources and equipment

• the Dynamic Risk Assessment process.

The officer is also responsible for the safety of those involved at the incident.

An OIC must provide adequate communication, supervision and support if

Information

putting people in harm’s way.

3.5.8 Communication

Communication is an essential tool for risk assessment and risk management.

Responsibilities:

Official

• firefighters report all hazards to their officer as soon as possible

• OIC Fire communicates hazards, hazard controls and risk management

procedures, to all staff at the incident.

the

This is an ongoing process throughout the incident as the situation changes, in

some cases, from minute to minute.

under

Released

January 2013

33

Incident Management – Command and Control

3.5.9 Acceptable risk

There are limits to the level of risk that you and the NZFS are expected to

accept and times when we will, and will not, risk our safety.

Acceptable risk

In a highly considered way, firefighters:

•

will take some risk to save saveable lives

•

may take some risk to save saveable property

Act

\ •

will not take any risk at all to try and save lives or properties that are

already lost.

Source - HM Government, Fire and Rescue

Manual, Volume 2, Fire Service Operations,

Incident Command, 3rd edition 2008

Information

The cardinal rule of rescue is ‘do not become a victim’.

3.6 Dynamic Risk Assessment

3.6.1 Dynamic Risk

To keep safe, you will need to manage the risks on the incident ground, even

Official

Assessment overview

when the situation is changing rapidly. This is called Dynamic Risk

Assessment (DRA).

DRA is an important part of the SPC, because you will encounter situations

the

when hazards arise that were not planned for, that are outside of your training,

and that need immediate response.

Dynamic risk assessment involves four main steps at recruit level:

1. identifying hazards

under

2. assessing the risk presented by hazards

3. identifying options to reduce the risk

4. deciding if the risk is acceptable or not acceptable.

Note: At officer level, DRA is used to decide on tactics and tasking at a

rapidly changing event.

Released

34

New Zealand Fire Service – National Training

Risk Assessment, Strategy and Tactics

Step 1: Identify hazards

The first step is to be aware of existing hazards and identify the potential for

unforeseen ones.

To apply the Safe Person Concept you must always be looking out for hazards.

This is true for any incident you respond to, whether it is going according to

plan, or whether it is a dynamically changing situation.

Just as you look both ways before crossing the road, you should always look

for potential dangers in your immediate working environment.

Act

Examples of common hazards include, but are not limited to:

• traffic

• heat

• electricity

• smoke

• environment

Information

• falling debris

• weakened structures

• people

Official

You must notify your OIC of hazards identified.

the

Step 2: Assess the risk

Once you have identified a hazard, you must assess how serious the risk is.

This will help you to decide what steps to take to reduce the risk.

The Risk Matrix, set out in the following section, is a useful tool for assessing

the risk.

under

Step 3: Identify options

If your OIC is not available, you may need to take action to reduce the risk

to reduce the risk

before you can proceed with the task.

Think about how you can eliminate, minimise or isolate the hazards to reduce

the risk. You may be able to lower the risk by reducing the likelihood and/or

consequence of something happening.

For example, when handling hot lights, you can minimise the likelihood

Released (chance) of getting burned, by wearing gloves.

January 2013

35

Incident Management – Command and Control

Step 4: Decide if the risk In an emergency incident it will not be possible to completely eliminate all

is acceptable

risk. Rather, with any particular hazard, risk assessment is about identifying

what risk is acceptable before proceeding with a task.

As a firefighter, you would not want to enter into a high risk situation, unless

there is no alternative. Before proceeding, you will need to consider whether

or not the existing risks are acceptable. Remember, we:

•

will take some risk to save saveable lives

•

may take some risk to save saveable property

Act

•

will not take any risk at all to try and save lives or properties that are

already lost.

3.6.2 DRA for OICs

As discussed above, recruits assess rapidly changing risk using a process

known as Dynamic Risk Assessment. This process is also used by OICs.

Your OIC will make decisions according to several risk management planning

techniques, including the Dynamic Risk Assessment process. The DRA

process flowchart is shown below to give you a picture of how decisions are

Information

made at a higher level.

Official

the

under

Released

36

New Zealand Fire Service – National Training

Risk Assessment, Strategy and Tactics

3.6.3 DRA process

flowchart (OIC level)

Identify objectives and

hazards

Assess risk

Act

Select strategy

Consider

AND tactics

alternatives

Carry out risk

assessment of

tactics

Information

Are the benefits

Implement control

worth the risk?

measures and

reassess tactics

Official

Yes

No

Select tasks

the

Can additional

achieve tactics

control measures

be introduced?

Yes

under

No

Proceed with tasks

DO

NOT PROCEED

(continual process)

Figure 3.9: Dynamic Risk Assessment model

Released

January 2013

37

Incident Management – Command and Control

As part of the scene size-up, the OIC will evaluate the tasks that need to be

undertaken and the risks associated with those tasks. The OIC will then select

tactics using DRA, and will only apply the tactics when the benefits are worth

the risk.

When carrying out a DRA, it may not be practical to take the time to formally

apply the risk matrix to assess the seriousness of the risk, then apply the DRA

process, and if the benefits are not worth the risk to introduce and implement

additional control measures and the reassess your tactics.

Act

Familiarity with applying the risk matrix in controlled situations, such as

training or discussion with others will help build your knowledge of the steps

in the process and confidence that in a rapidly changing situation, you can

apply new controls knowing that the risk is reduced and your tactics have

resulted in safer tasking.

3.6.4 Likelihood x

At times, you may be required to put yourself at some risk to carry out required

consequence = risk

tasks. The Risk Matrix is a visual tool to give you an idea about how to assess

the seriousness of a risk.

Information

‘Likelihood x Consequence = Risk’ is a way of thinking. In every response

situation, a firefighter must be actively thinking about potential hazards in

terms of likelihood, consequence and risk.

Likelihood

the chance of something happening

Consequence

the outcome or impact if it does happen

Official

Risk

this is the chance of something going wrong

The OIC will carry out the initial risk assessment at an incident. Then they will

the

select the tactics and tasks that will reduce the likelihood and/or consequence

of hazards, to reduce the risk.

Likelihood

Likelihood is the

chance, frequency or

probability that something will happen.

For example, if a car is approaching as you cross a road, there is some

under

likelihood that you could be hit.

Every day people safely cross the road. The likelihood of being hit is ‘rare’,

provided the risk is minimised by crossing while the car is still a safe distance

away.

Consequence

Consequence is the outcome or impact of something happening. A

consequence could be financial, operational (damage to equipment, impact on

strategy), personal, physical or psychological.

Released With the example above, a consequence of being hit could be physical injury.

Depending on the impact, the physical consequences could be minor,

moderate, major or catastrophic. Even if the physical consequences are minor,

the psychological consequences could be major.

38

New Zealand Fire Service – National Training

Risk Assessment, Strategy and Tactics

Risk

Risk, in the context of dealing with an emergency incident, is about the danger

involved. To understand the overall risk, the likelihood of something

happening must be considered along with the consequences it would have if it

did happen.

The decision you make about when to cross the road is based on the level of

risk you are prepared to take. By looking both ways before crossing the road,

you can lessen the risk of injury, by reducing the likelihood of being hit. The

consequences of being hit are affected by other factors, like the speed of the

car.

Act

3.6.5 Categories of

The following tables describe likelihood, consequence and risk.

likelihood

LIKELIHOOD

Descriptor

Description

The chance of something

happening

Almost

Is expected to occur

Greater than a 90% chance of

certain

occurring

Likely

Will probably occur

Between a 70% to 90% chance

Information

of occurring

Possible

Might occur

Between a 30% to 70% chance

of occurring

Unlikely

Could occur

Between a 10% to 30% chance

of occurring

Official

Rare

May occur in

Less than a 10% chance of

exceptional

occurring

circumstances

the

3.6.6 Categories of

CONSEQUENCE

consequence

Descriptor

Examples*

Catastrophic

Fatality(ies) to staff; catastrophic loss of operational

under capability (e.g., three appliances out of use)

Major

Multiple serious injuries (e.g., permanent disability);

major loss of operational capability (e.g., loss of one

appliance)

Moderate

Serious injury (e.g., hospital, off work); moderate

loss of equipment (e.g., broken ladder)

Minor

Minor injury; minor loss/damage to equipment (e.g.,

standpipe knocked out of ground)

Released Insignificant Insignificant injury or damage/loss to equipment

(e.g., burst length of hose)

*Descriptions in this table relate to the degree of injury or loss of operational

capability. Consequences may also occur in other context (e.g. financial, loss

of reputation, public image).

January 2013

39

Incident Management – Command and Control

3.6.7 Risk Matrix

The matrix below can be used to assess the risk associated with the likelihood

and consequences of an event. Risks with the highest ratings should be dealt

with first.

In an emergency incident, you will not be referring to the risk matrix to make

decisions. But, it is important to understand the concept. The higher the

likelihood and consequence, the greater the risk.

For example, if a hazard presents a high likelihood of causing a problem, and

the consequences would be high, you must consider the risk very high and take

the appropriate steps to manage the risks.

Act

CONSEQUENCES

LIKELI-

HOOD

In-

Cata-

Minor

Moderate

Major

significant

strophic

Almost

Low

Medium

Very high

Very high

Very high

certain

Likely

Low

Medium

High

Very high

Very high

Information

Possible

Low

Medium

High

Very high

Very high

Unlikely

Low

Low

Medium

High

Very high

Official

Rare

Low

Low

Medium

High

High

the

under

Released

40

New Zealand Fire Service – National Training

Risk Assessment, Strategy and Tactics

3.6.8 Example

The following example demonstrates the Dynamic Risk Assessment at work.

You have responded to a garage fire in a residential area. Upon arrival you do a

risk assessment and decide to proceed with an internal attack.

The first crew in relay back that there is an acetylene cylinder in the garage.

You use the Dynamic Risk Assessment to decide what new strategy and tactics

to use (if any).

Act

Likelihood

Has the cylinder been involved in the fire?

Yes/No

• If

Yes then the likelihood of risk would be

Likely that something may

occur relating to the cylinder because of exposure to the heat from the

fire.

• If

No then the likelihood would be

Unlikely that anything will occur as

a result of exposure to the heat from the fire.

Information

Consequences

What would the consequences be if the cylinder became or was involved in