ACT

INFORMATION

RELEASED UNDER THE OFFICIAL

link to page 3 link to page 4 link to page 4 link to page 5 link to page 6 link to page 7 link to page 8

Contents

BACKGROUND

2

GOVERNMENT SURVEY

3

Why do you think dogs attack?

3 ACT

What do you think is the best way to reduce dog attacks?

4

What can owners do?

5

What can local councils do?

6

What can central government do?

7

HOW NZKC CAN ASSIST

8

INFORMATION

E OFFICIAL

RELEASED

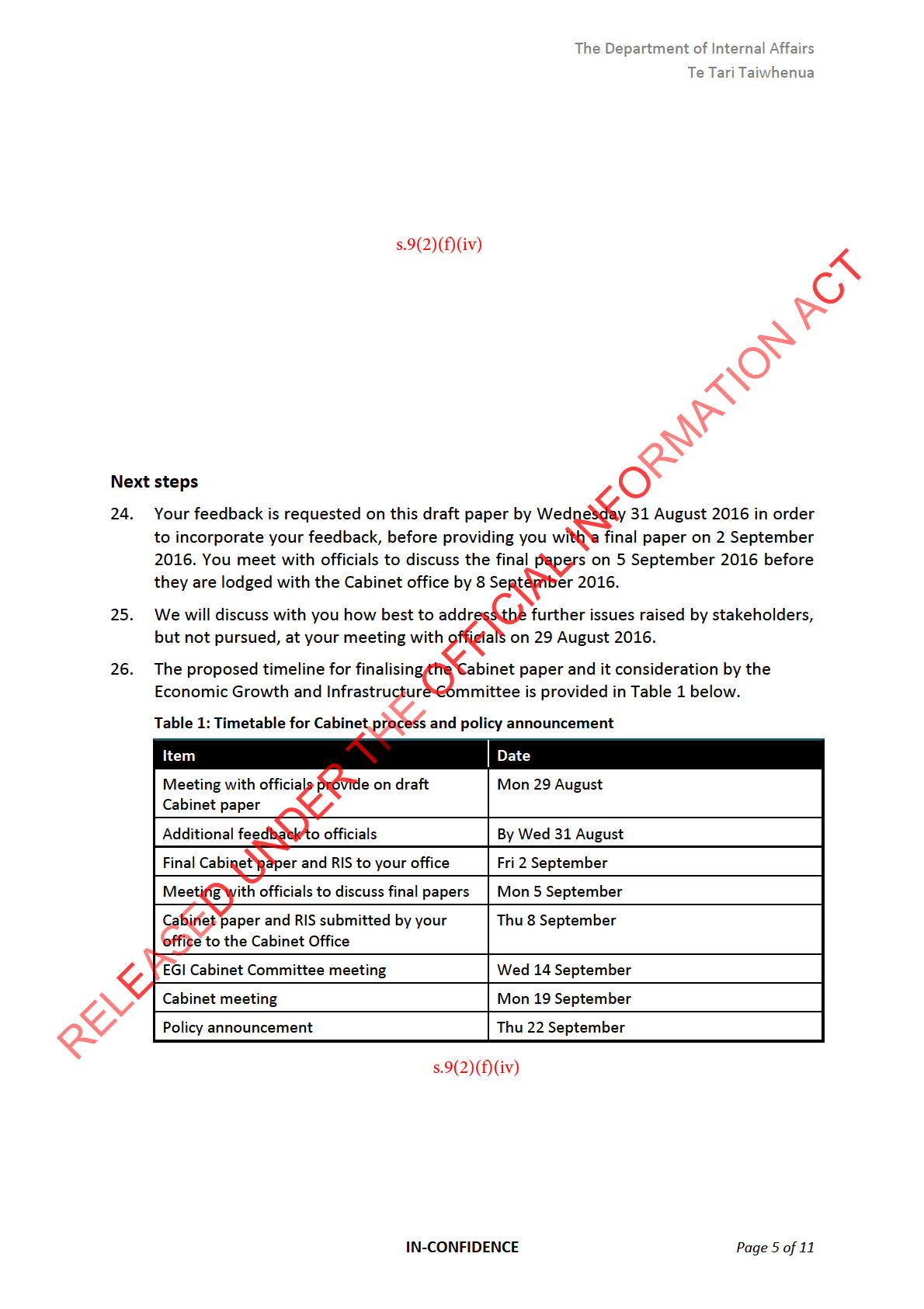

RELEASED UNDER THE OFFICIAL

1

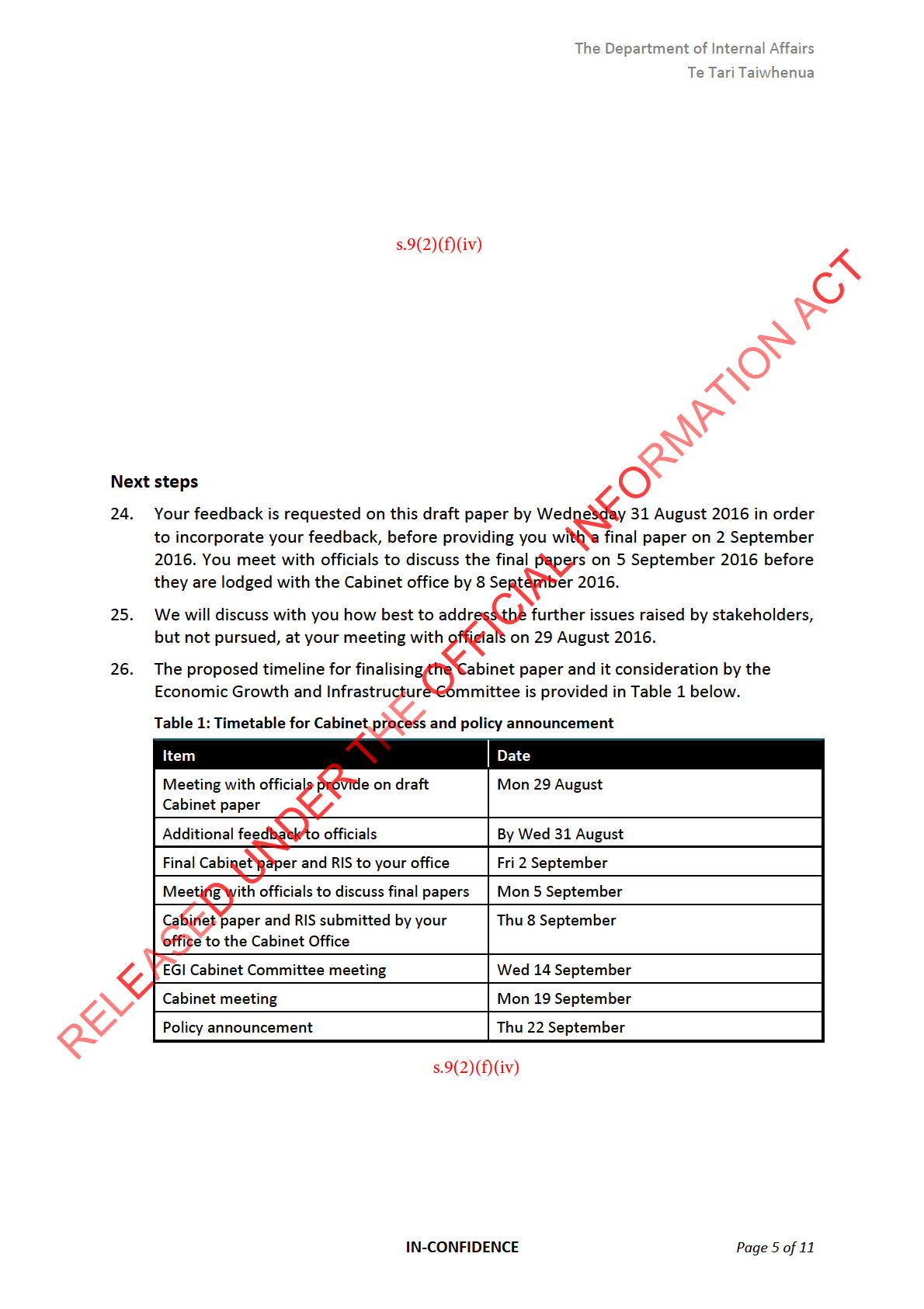

BACKGROUND

The New Zealand Kennel Club (NZKC) is the largest organisation of dog owners in New

Zealand. Currently it is a ‘club of clubs’ and a ‘club of individuals’ with about 5,700

individual members spread across 287 clubs throughout New Zealand. NZKC was formed in

1886 and is an incorporated society.

NZKC is very much based on the celebration of the benefits of the dog/human relationship

for individuals of all ages and recognise that dogs are part of our community and working ACT

dogs are an essential part of our success as an agricultural country.

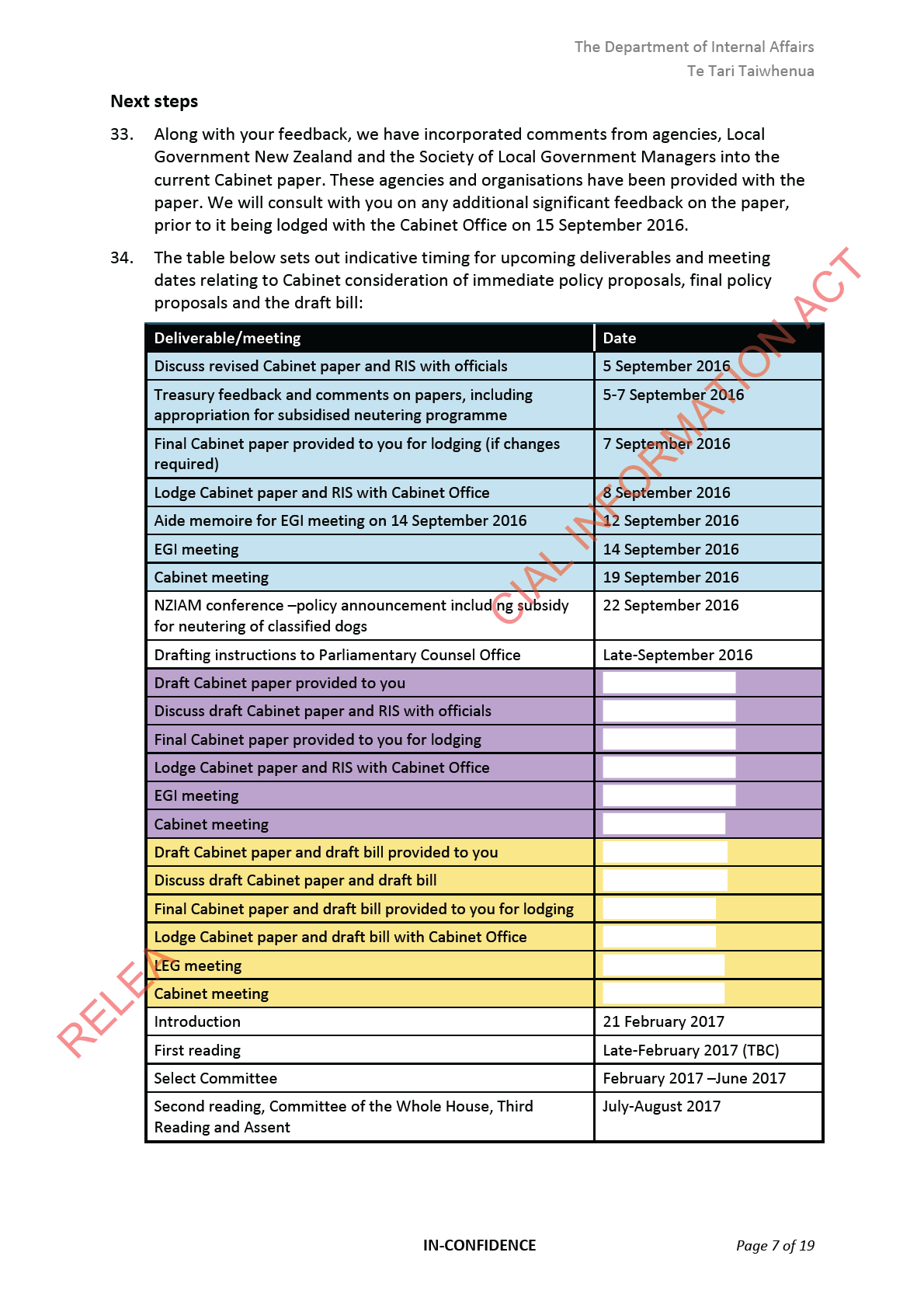

NZKC is the umbrella organisation for three main disciplines:

Conformation ( 65% of membership)

Agility (21 %)

Obedience (14%)

All three disciplines are involved in their own range of sports and competitions which are

INFORMATION

the cornerstone of NZKC’s existence.

In addition our conformation membership is very heavily involved in the breeding and sale

of (pedigree) pure bred dogs. The NZKC maintains a registry for 218 recognised breeds of

dog where qualification requirements must be met e.g. a three generation pedigree for the

dog must be available and the NZKC member must have been granted a NZKC kennel name

i.e. a licence to breed and register progeny.

E OFFICIAL

The other area the NZKC membership is heavily involved in is the provision of domestic dog

training/owner education throughout New Zealand. This service is provided by

approximately 300 volunteers from 46 Obedience clubs. Approximately 12,000

puppies/dogs are trained per annum under the umbrella of the internationally acclaimed

Canine Good Citizen programme which the NZKC administers in this country.

RELEASED

RELEASED UNDER THE OFFICIAL

2

GOVERNMENT SURVEY

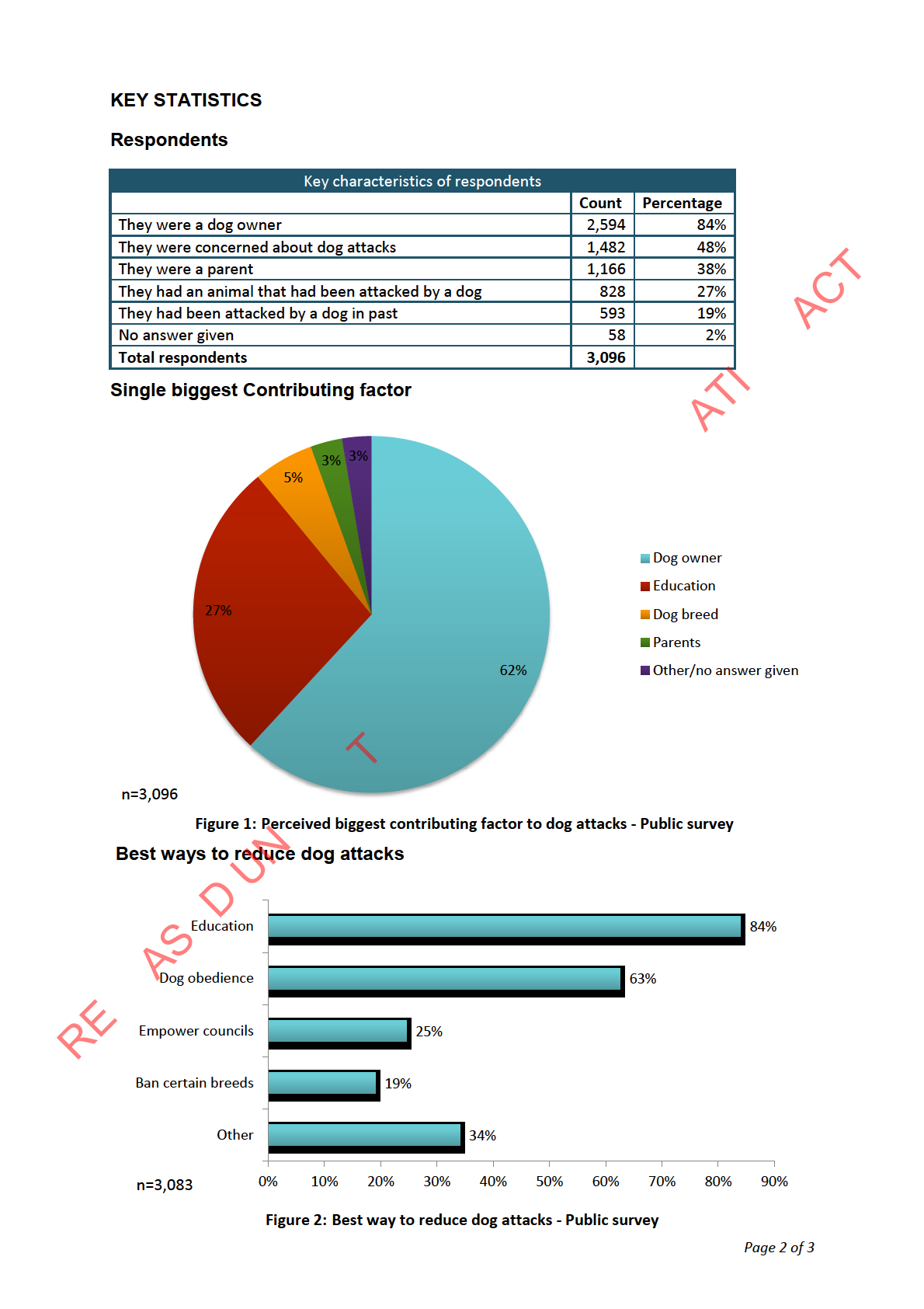

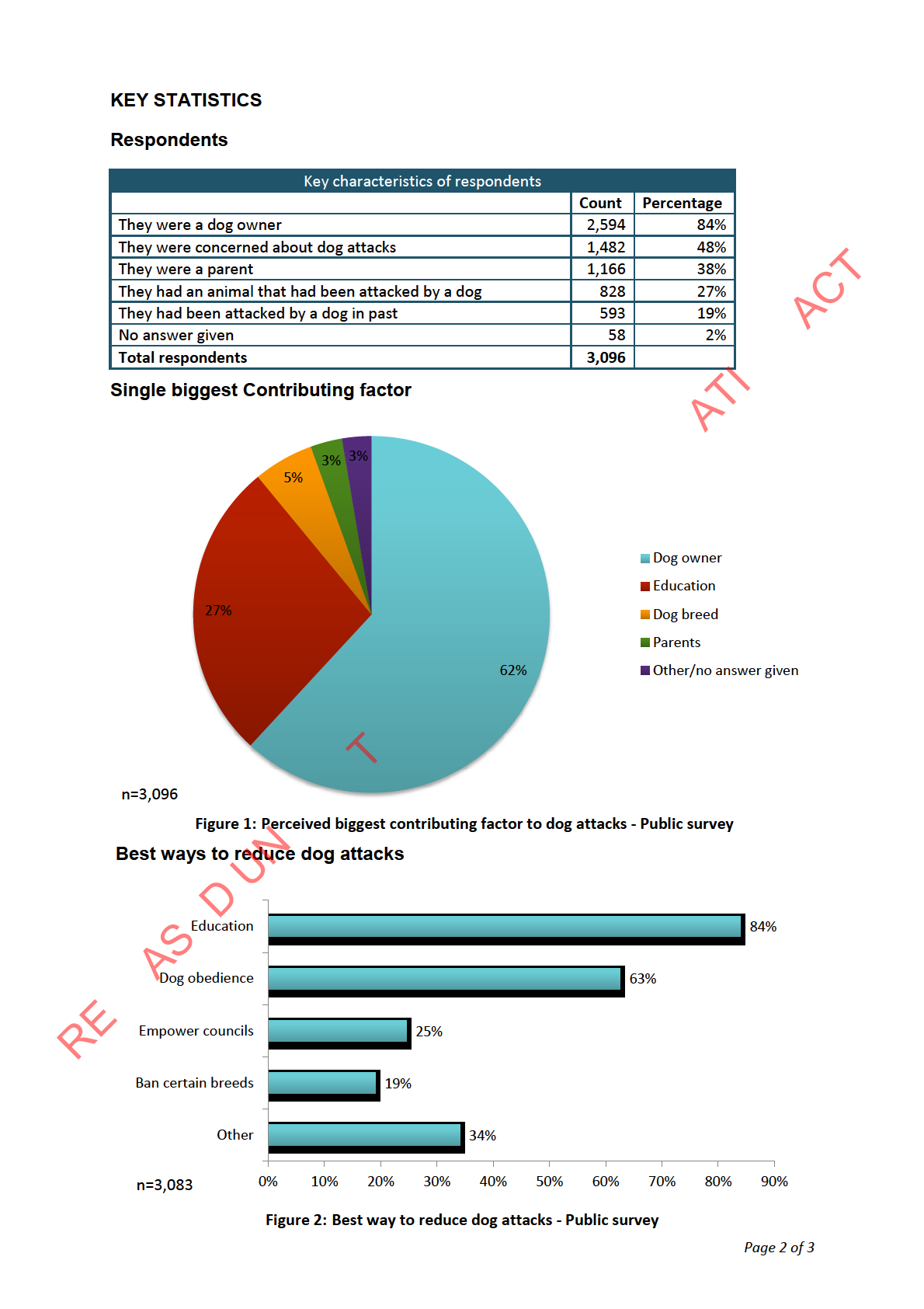

Why do you think dogs attack?

Any dog has the capacity to attack with the potential to damage heightened in a pack

situation.

Dogs attack as a reaction to a stressful situation. They may attack because they’re scared

or threatened. They may attack to protect themselves, their puppies, their food, their

ACT

property or their owners. They may attack if they’re not feeling well, in pain or if they’re

startled, and they may also nip or bite during play (which is why rough play should be

avoided to ensure that the dog is not overly excited).

NZKC agrees with the body of international research and experience that breed specific

legislation does not work. Dog aggression is more complex than simply genetics. However,

there are breeds that owners and the public need to be mindful of as some have the

potential to do more damage than others when they do attack or bite. This does become a

double edged sword as a fear of dogs can fuel aggression by the animal. This fear can be

INFORMATION

stimulated by media focus and attention particularly when certain breeds or types are

identified.

The NZKC believes that the biggest contributing factor to dog attacks is a lack of education

1) of owners 2) of the dogs themselves (lack of training) and 3) of the non-dog owning

public and children in particular.

An animal is part product of its environment. We fully understand that this is a very

E OFFICIAL

complex issue. There is a segment of the population who already do not comply with

central and local government requirements e.g. not to register their dogs and they are

then less likely to be involved in what we see as being of the greatest benefit i.e. an

increase in dog training and owner education. Experience tells us that this same segment

are more likely to be attracted to dogs with that potential to do more damage when they

bite.

RELEASED

RELEASED UNDER THE OFFICIAL

3

What do you think is the best way to reduce dog attacks?

NZKC believes the best way to reduce dog attacks is through education. We are New

Zealand’s largest service provider in this area. As reported in this document the NZKC has

46 member clubs spread throughout New Zealand delivering dog training classes and

owner education under the banner of the internationally acclaimed Canine Good Citizen

programme. This training and education is open to all i.e. not restricted to NZKC

members.

ACT

NZKC believes all dog owners should attend dog training classes and, as much as possible,

involve all family members associated with the dog. As a minimum requirement NZKC

believes that dog training and owner education should be mandatory for the registered

owner of the dog. We also believe that dog training as such needs to be defined i.e. it is

more than attendance at puppy classes. An analogy can be drawn with child education. It

does not stop after kindergarten.

NZKC questions the process involved in the re-homing of unwanted dogs. Is the process

INFORMATION

rigorous enough in ensuring that these dogs are suitable for re-homing when many have

had extremely unfortunate circumstances to contend with and consequently, through no

fault of their own, have the potential to attack and damage?

The first step in a model going forward must be to identify all parties currently involved in

any legislative, educational and management capacity regarding dogs and dog

OFFICIAL

ownership. In simple terms this would be a stocktake of interested parties to establish the

starting point for strategies and plans to be developed and resources targeted to ensure

both dog owners and non-owners alike will feel safer within their environments.

The NZKC is becoming increasingly aware of the number of individuals and/or groups

becoming involved in dog safety education programmes, in schools in particular, however,

there does not appear to be any protocols in place to ensure that the programmes being

delivered are best practice models.

RELEASED UNDER THE

RELEASED UNDER THE OFFICIAL

4

What can owners do?

Generally the problems appear to lie with those individuals who own unregistered dogs.

The first step must be to target and upskill these owners.

Dog attacks will be reduced to some extent by dogs being kept on a leash. However, one

key reason that dogs are not kept on a leash is that owners have trouble controlling them

when the dog is restrained in this manner and this once again reinforces the need for

education and training.

ACT

There is also very sound reasoning to have dangerous and menacing dogs classified as

requiring muzzles when in public. NZKC supports the legislation already in place and any

common sense approach to an extension of it. We do not support breed specific

legislation.

All properties with dogs should be fenced. All citizens have a right to walk with or without

a dog on our streets without the fear of a dog rushing out at them

NZKC is of the belief that a fit and active dog is a much better companion animal and

INFORMATION

member of society. Consequently, NZKC is also heavily involved in a wide range of

competitions and sports which cater for both pure bred and cross bred dogs. We believe

owners should be encouraged to become involved in any club or organisation offering

services based on dog socialisation and activities.

E OFFICIAL

RELEASED

RELEASED UNDER THE OFFICIAL

5

What can local councils do?

NZKC sees local councils as having a responsibility to keep their citizens safe and that this

responsibility extends to safety from irresponsible dog owners and their dogs. We believe

that the local council’s funding policies should clearly distinguish between the services

provided for compliant dog owners and those who are non-compliant. A likely outcome of

the drive to make dog owners and the general public safer will be increased costs and the

NZKC and its membership do not wish to share in this cost any more than other

responsible dog owners and the general public.

ACT

We believe that a first step for local councils is a concerted drive to target the owners of

unregistered dogs. NZKC is aware of and applauds Auckland City Council’s recent

initiative. We are very interested in the outcomes in terms of the affected dogs and the

part that education and training has to play in these situations. We are also interested in

what resource is required for such targeting of non-compliant owners and any subsequent

education and training.

NZKC believes that the services provided by the Animal Management groups within local

government bodies are extremely valuable and to the best of our knowledge executed

INFORMATION

very well. We believe this needs to be further resourced, particularly in the short to

medium term, targeting dangerous dogs which are more likely to be unregistered.

We reinforce our desire to see greater co-ordination in relation to dog education and

training as it applies to local councils and their Animal Management teams. NZKC sees a

role for local councils in the monitoring and auditing of dog training and owner education

particularly if it is to become mandatory as recommended.

E OFFICIAL

NZKC believes the costs associated with services provided as a result of non-compliant

owners should not fall solely on compliant dog owners i.e. they should be borne evenly by

all ratepayers.

RELEASED

RELEASED UNDER THE OFFICIAL

6

What can central government do?

NZKC believes central government must take a greater role in raising public awareness

about safety around dogs and take a co-ordination role of those involved in dog education

and dog ownership and the benefits of it for dog owners and the general public. The latter

may be a short to medium term position for central government and the Department of

Internal Affairs in particular. There certainly appears to be a disjointed approach to dog

education in New Zealand and NZKC sees itself is part of that disjointedness. We recognise

the work we are doing in this area is not well known but this is work in progress with

ACT

initiatives set out in this document. (Refer last section in particular).

In recent years, a strong correlation between domestic violence, animal abuse and the

incidence of aggressive dog behaviour has been established. Child and animal protection

professionals have recognised this link. Anecdotal evidence from within NZKC and those

involved in dog training also supports this link e.g. dogs chained unnecessarily and/or not

exercised etc. and aggressive behaviour. Animal cruelty is one of the earliest and most

dramatic indicators that an individual is developing a pattern of seeking power and

control through abuse of others. When animals in a home are abused or neglected, it is a

warning sign that others in the household may be in danger. When looking at this from a

INFORMATION

dog attack perspective why would any household, where family violence has been

identified, be allowed to own dogs?

NZKC would like to see more police intervention and support of local government Animal

Management services to ensure that non-compliant owners have their dogs impounded

and any household with domestic violence issues is are treated similarly.

E OFFICIAL

RELEASED

RELEASED UNDER THE OFFICIAL

7

HOW NZKC CAN ASSIST

NZKC has for some time been considering the challenges and opportunities involved with

the expansion of our services in the dog owner education/dog obedience areas. In recent

times the subject of Dangerous Dogs was a topic of discussion at NZKC’s June 25, 2016

Annual Conference. A panel of outside parties was involved including representatives

from NZVA, SPCA and Wellington City Council. A summary of the discussion and NZKC’s

previous considerations and ensuing, possible solutions is provided below.

ACT

It was clearly felt that a great deal of work and outside support would be required for

NZKC, our member clubs and volunteers to extend our services to encompass reactive,

difficult and dangerous dogs.

Furthermore, as the current services provided are nearly all undertaken by volunteer

personnel any extension of these services to encompass more dogs (and their owners)

would similarly require a great deal of work and outside support.

These challenges are well understood and the organisation has discussed a range of

solutions, including:

INFORMATION

•

NZKC business model prepared to include self-funding opportunities

•

Meeting organised with interested groups – NZKC/DIA/LGNZ/ACC/SPCA/NZVA

etc.

•

Conference held in mid-2017 bringing together personnel from NZKC’s 46 member

clubs to establish a best practice model

•

Discussions continue with tertiary institutions in establishing a tiered course for

E OFFICIAL

dog trainers

•

Regional seminar training programme be established (training the trainers)

•

Relationships developed between NZKC member clubs and private trainers

•

NZKC organises an open to all, annual dog trainers conference

•

NZKC introduces pilot schemes to bring together interested parties – 2016

NZKC/Central All Breeds Dog Training Club/Wellington City Council/2017 similar in

Porirua.

NZKC currently has no set view on either owner licencing and/or breeder licencing. We are

already involved in both and more particularly the latter. Nearly 50% of NZKC’s members

(2,867) have active kennel names i.e. a licence to breed and register the progeny. These

members are bound by NZKC Rules, Regulations and a Breeders Code of Ethics. There are

also standards in place for the granting of a new kennel name. Nearly 8,000 puppies are

RELEASED

RELEASED UNDER THE OFFICIAL

registered annually of which approximately 60% are sold to the public. Therefore, the

NZKC and its breeders have responsibilities to raise puppies that are well socialised and an

opportunity to educate new owners as to their responsibilities.

8

ACT

INFORMATION

E OFFICIAL

RELEASED

RELEASED UNDER THE OFFICIAL

ACT

INFORMATION

RELEASED UNDER THE OFFICIAL

ACT

INFORMATION

RELEASED UNDER THE OFFICIAL

ACT

INFORMATION

RELEASED UNDER THE OFFICIAL

ACT

INFORMATION

E OFFICIAL

RELEASED

RELEASED UNDER THE OFFICIAL

ACT

INFORMATION

E OFFICIAL

RELEASED

RELEASED UNDER THE OFFICIAL

ACT

INFORMATION

E OFFICIAL

RELEASED

RELEASED UNDER THE OFFICIAL

ACT

INFORMATION

s.9(2)(a)

RELEASED UNDER THE OFFICIAL

ACT

INFORMATION

RELEASED UNDER THE OFFICIAL

ACT

INFORMATION

RELEASED UNDER THE OFFICIAL

ACT

INFORMATION

RELEASED UNDER THE OFFICIAL

ACT

INFORMATION

RELEASED UNDER THE OFFICIAL

ACT

INFORMATION

RELEASED UNDER THE OFFICIAL

CT

ACT

INFO

INFORMATION

OFFICIAL

D UNDER T

E

RELEASED UNDER THE OFFICIAL

ACT

INFORMATION

s.9(2)(a)

RELEASED UNDER THE OFFICIAL

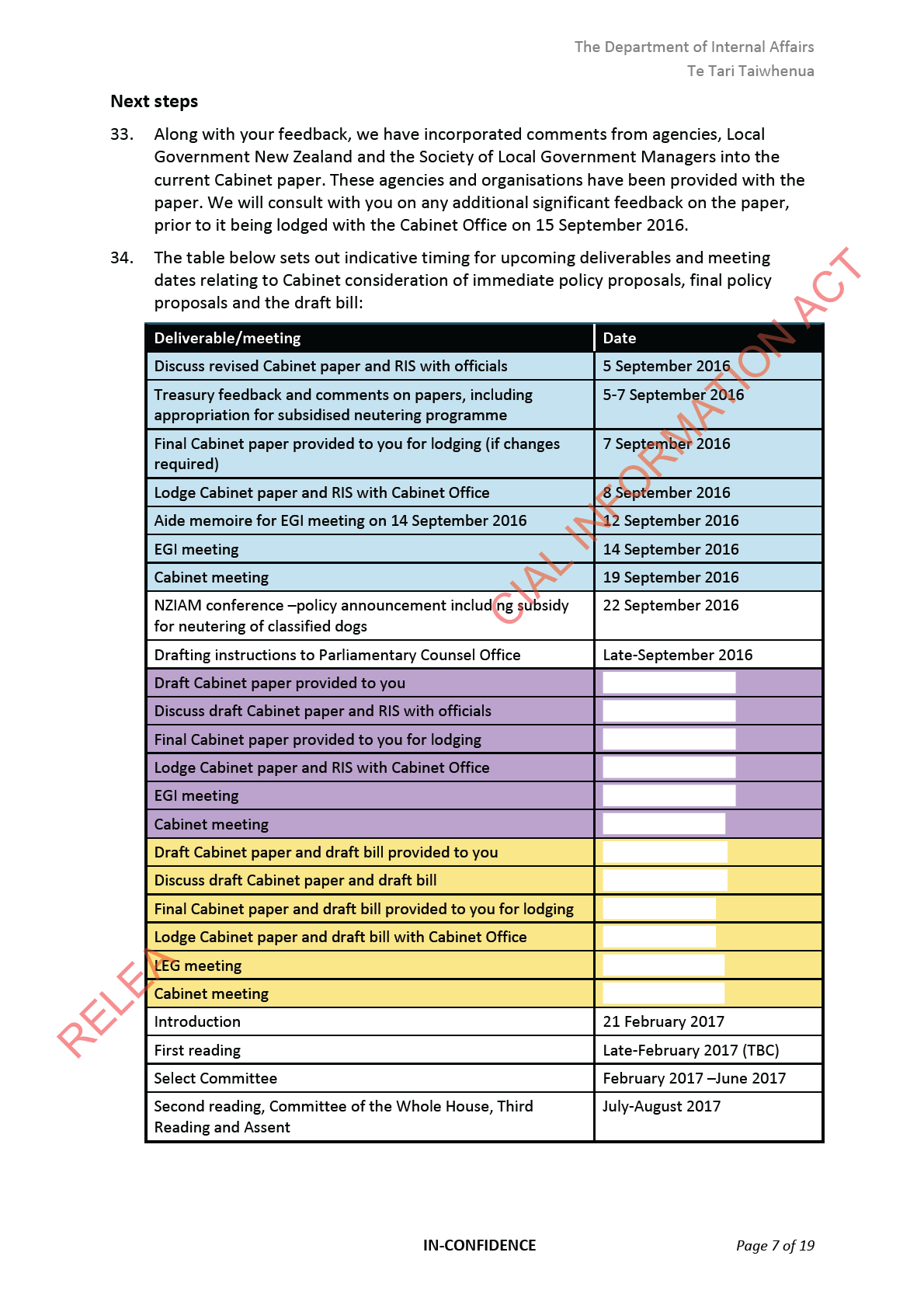

The Department of Internal Affairs

Te Tari Taiwhenua

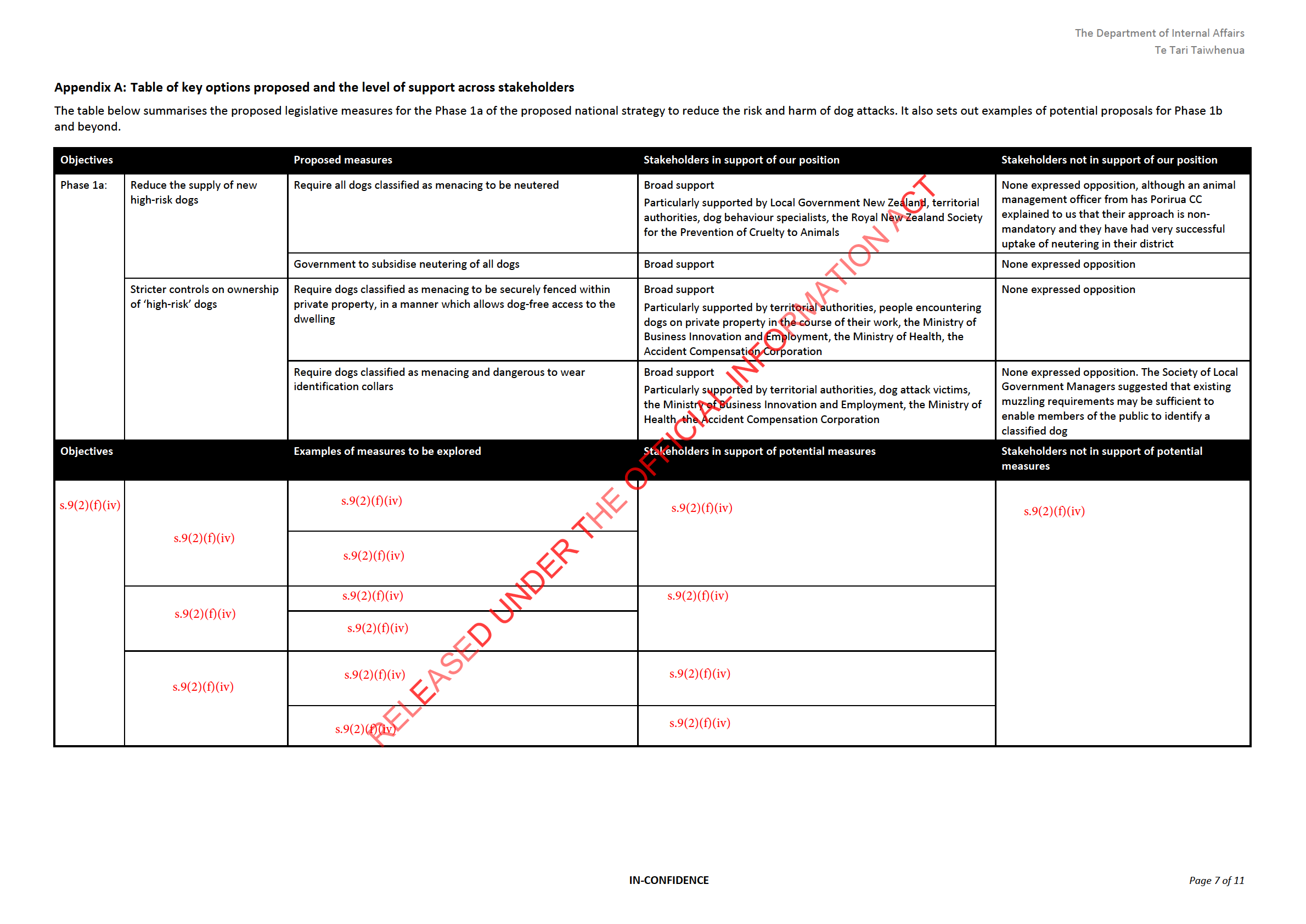

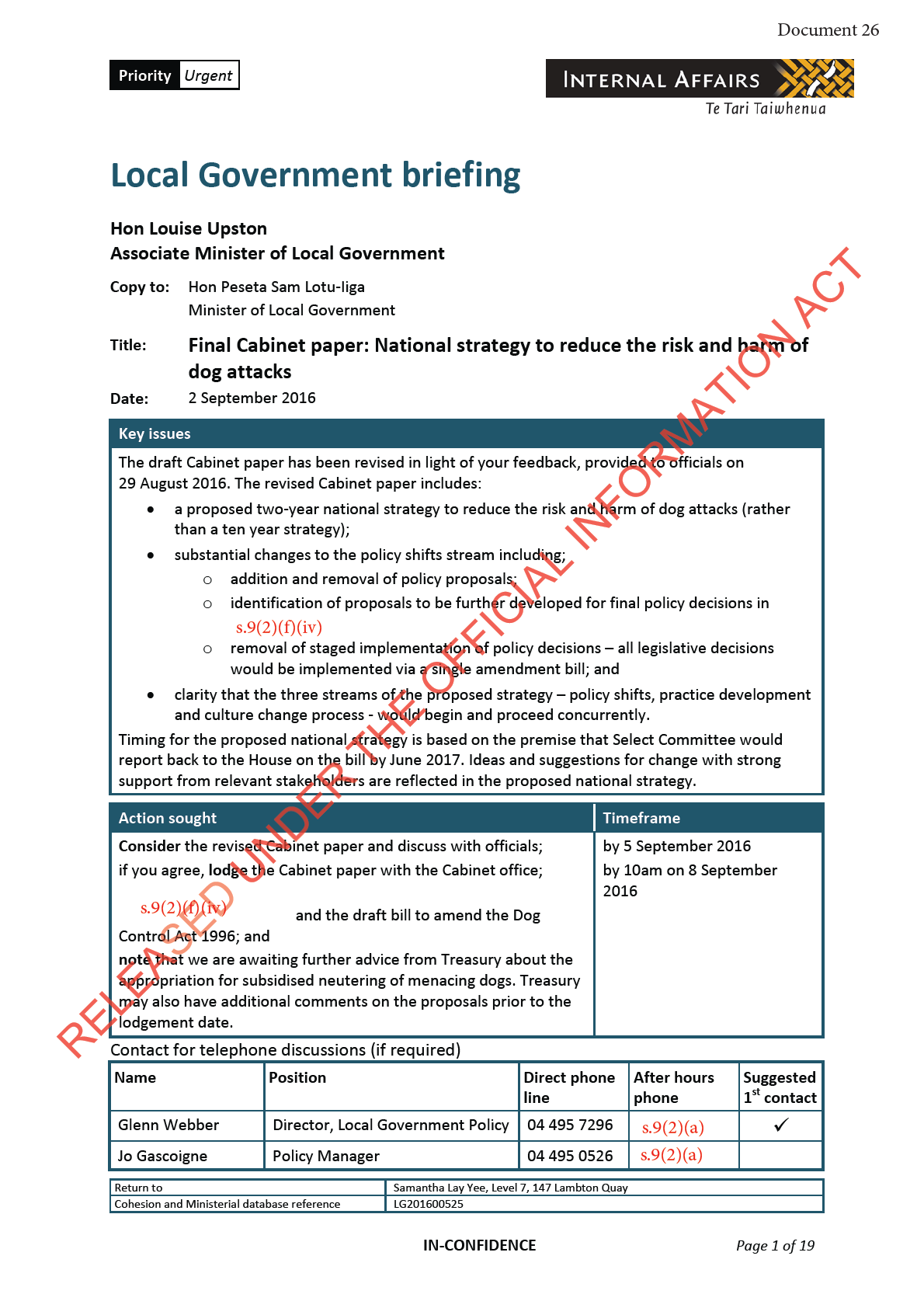

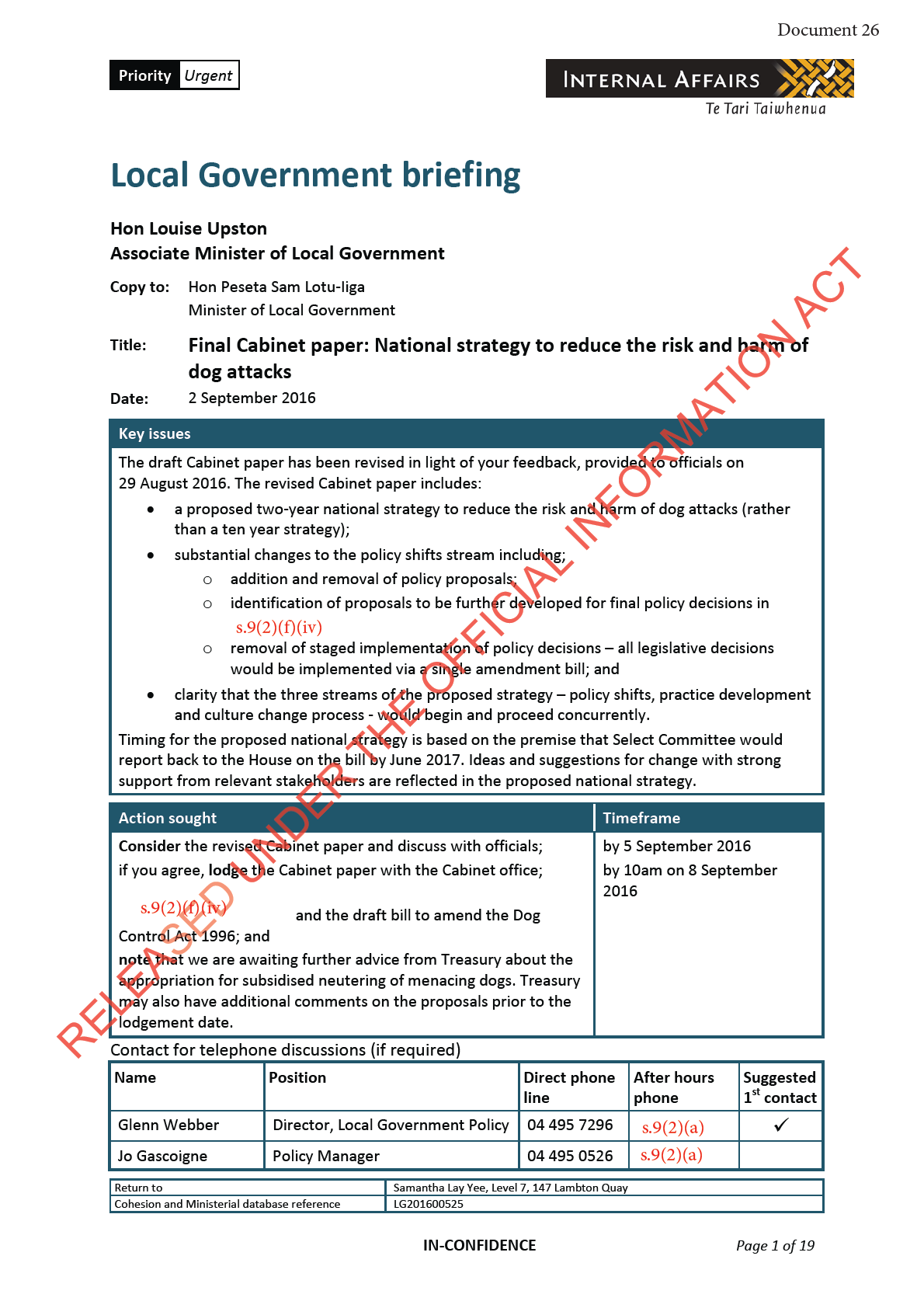

Purpose

1.

The purpose of this briefing is to advise you on options to reduce the risk and harm of

dog attacks in New Zealand. It attaches:

An overview of the proposed strategy to reduce the risk and harm of dog attacks,

showing an indication of stakeholder support (Appendix A);

a draft Cabinet paper based on officials’ preferred options, for your review

(Appendix B);

the draft Regulatory Impact Statement supporting the Department’s analysis and

CT

proposed options (Appendix C); and

ACT

a summary of council and public feedback on proposed measures, and a media

release to announce the results and thank submitters (Appendix D).

Executive summary

2.

You intend to seek Cabinet’s agreement to proposals to reduce the risk and harm of

serious dog attacks in New Zealand. This is with a view to announcing decisions at the

annual New Zealand Institute of Animal Management conference being held on 22

September 2016.

3.

We propose a package of measures, which collectively form a national strategy, that

INFO

INFORMATION

achieve the goal of reducing serious dog incidents The draft Cabinet paper provides an

overview of the strategy.

Key findings that underpin our analysis on how to reduce risk and harm

4.

The Department’s analysis is summarised in the attached draft Regulatory Impact

Statement. That Regulatory Impact Statement is currently being assessed by the

OFFICIAL

Department’s internal regulatory impact analysis panel and is subject to additional

changes. We have provided it in draft form to act as supporting information as you

consider the proposed strategy.

5.

As part of our discussions with stakeholders and scan of literature, we have identified

the following key findings, which form the basis of the proposed policy position on

how to reduce the risk and harm of serious dog attacks.

Breed-specific legislation alone does not reduce the number of dog attacks

6.

International experience has indicates that breed-specific approaches have not been

D UNDER T

successful in reducing dog attacks, and the trend observed internationally is a move

away from this approach. Specifically, it shows that:

breed alone is not an appropriate indicator or predictor of aggression in dogs.

E Rather, certain breeds have a greater propensity for harm should they attack.

Focussing on particular breeds fuels the misperception that other dogs won’t bite;

RELEASED UNDER THE OFFICIAL

it is not possible to precisely determine the breed of the types of dogs targeted by

breed-specific legislation by visual identification or by DNA analysis; and

a breed-specific approach does not address the human element whereby dog

owners who desire a classifiable dog will simply substitute another breed of dog of

similar size, strength and perception of aggressive tendencies.

7.

Risk of attack and

harm of attack are two separate areas of policy action, which can

often get conflated. All dogs have potential for aggression and carry risk of attack; the

IN-CONFIDENCE

Page 2 of 11

The Department of Internal Affairs

Te Tari Taiwhenua

dog breeds and type in Schedule 4 of the Dog Control Act 1996 have a greater

potential to inflict significant harm. This is a sound rationale for placing greater

precautionary controls on the keeping of these dogs. However, other measures are

needed to address risk of attack.

Increasing controls and costs of ownership risks further disincentivising dog registration

8.

Dog registration is the cornerstone of effective dog control. This is because it links dog

control services to dog owners; allows for the appropriate placement of controls on

individual dogs; and provides a source of revenue for dog control activities. Dog

control policy needs to balance the need to have strict and appropriate controls in

CT

ACT

place for ‘higher risk’ dogs (which drives up compliance costs for their owners), with

the need to ensure dog ownership is not pushed further ‘underground’.

9.

Any additional cost may act as a discouragement from complying with requirements

such as registering dogs, or encourage irresponsible behaviours such as dumping dogs.

Having a dog classified as menacing is an important first step in being a responsible owner

10.

It is important that being the owner of a dog classified as menacing is not stigmatised,

and that policies around those owners, and their dogs, not are punitive in nature. This

is because the menacing classification system is designed to put extra protections

around those dogs so that they may be accepted into a society that is aware of and

INFO

INFORMATION

minimises the extra risk associated with these dogs. Having the appropriate controls

will mean ‘menacing’ dogs do not become ‘dangerous’ dogs. It may be more

appropriate to think of these dogs as ‘potentially dangerous’ rather than menacing.

Most dog incidents occur in the home; children are disproportionately involved in serious

dog attacks

OFFICIAL

11.

Both ACC claim and hospitalisation data show that most dog-related injuries and

incidents occur in the home. This finding is supported by findings overseas1 and what

we have heard from dog control officers we have met with.

12.

According to an analysis of hospitalisation data carried out by the University of Otago’s

Injury Prevention Unit, just under 30 per cent of the patients discharged for serious

dog bite incidents (excluding day patients) were under the age of 10. SPCA New

Zealand and other stakeholders we have met with also discussed the fact the children

are disproportionately affected.

D UNDER T

To be effective, policy tools need to be used in a phased approach

13.

There are a number of policy tools available to deal with dog control issues. These

nclude registration and licensing obligations; registration and licensing differential

Efees incentives; and classification of dogs or owners. Some of these tools we are

currently using; others could be adopted. All have merit in theory, but have practical

issues. We consider that the success of these further measures depends on the

RELEASED UNDER THE OFFICIAL

receiving environment being right.

14.

Currently dog control in New Zealand is significantly hampered by the high availability

of dogs. As such, ‘supply-side’ measures first need to be adopted to reduce the

1 Australian Veterinary Association

“Dangerous dogs – a sensible solution: Policy and model legislative

framework” (August 2012).

IN-CONFIDENCE

Page 3 of 11

The Department of Internal Affairs

Te Tari Taiwhenua

availability of high-risk classified and dangerous dogs. This combined with a societal

culture change process and more effective council action through development of best

practice, will mean the conditions are ripe for ramping up controls on dogs, owners

and breeders. This leads us to propose a package of amendments, which collectively

form a national strategy.

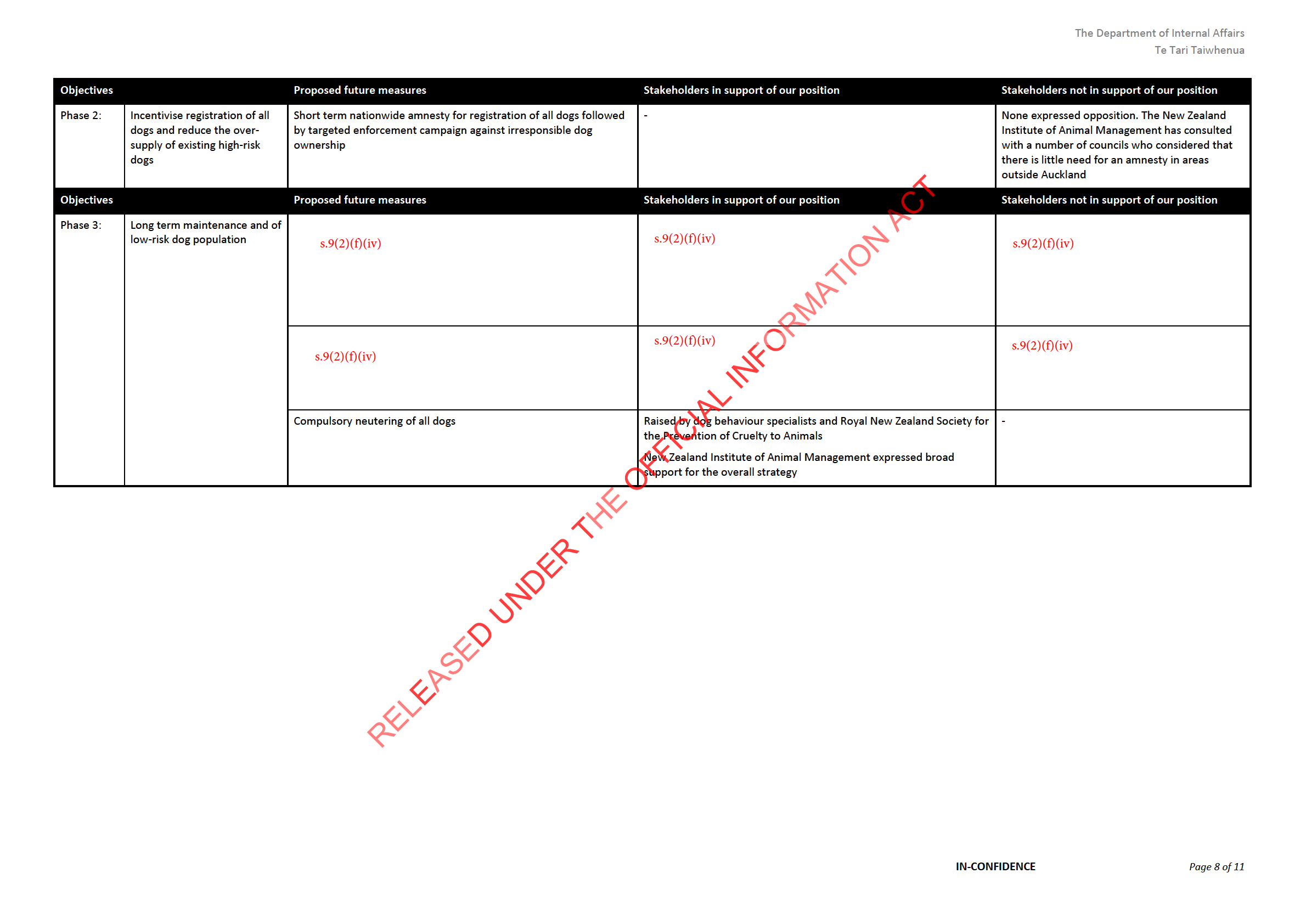

The attached draft Cabinet paper proposes a national strategy to reduce the risk

and harm of dog attacks

15.

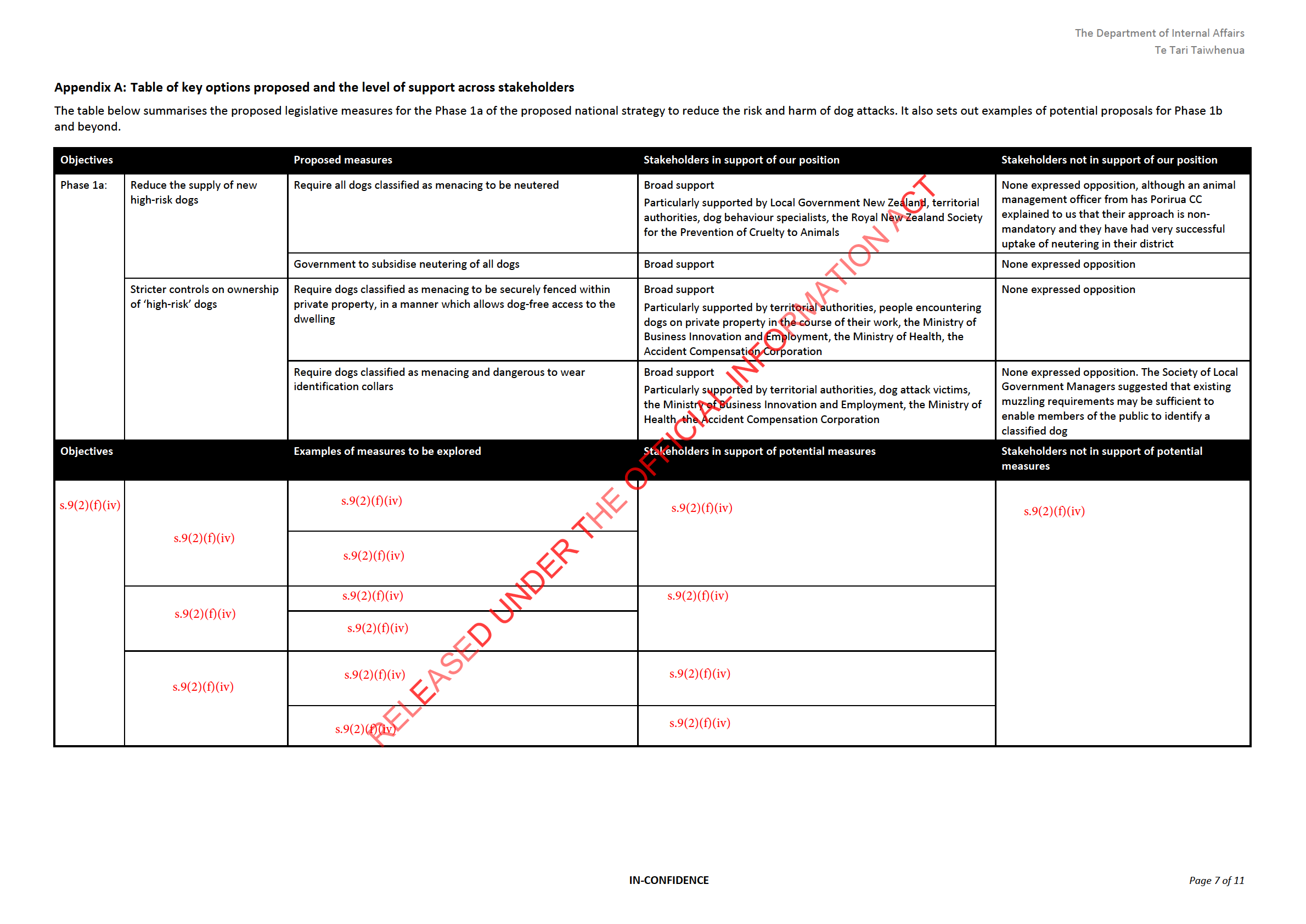

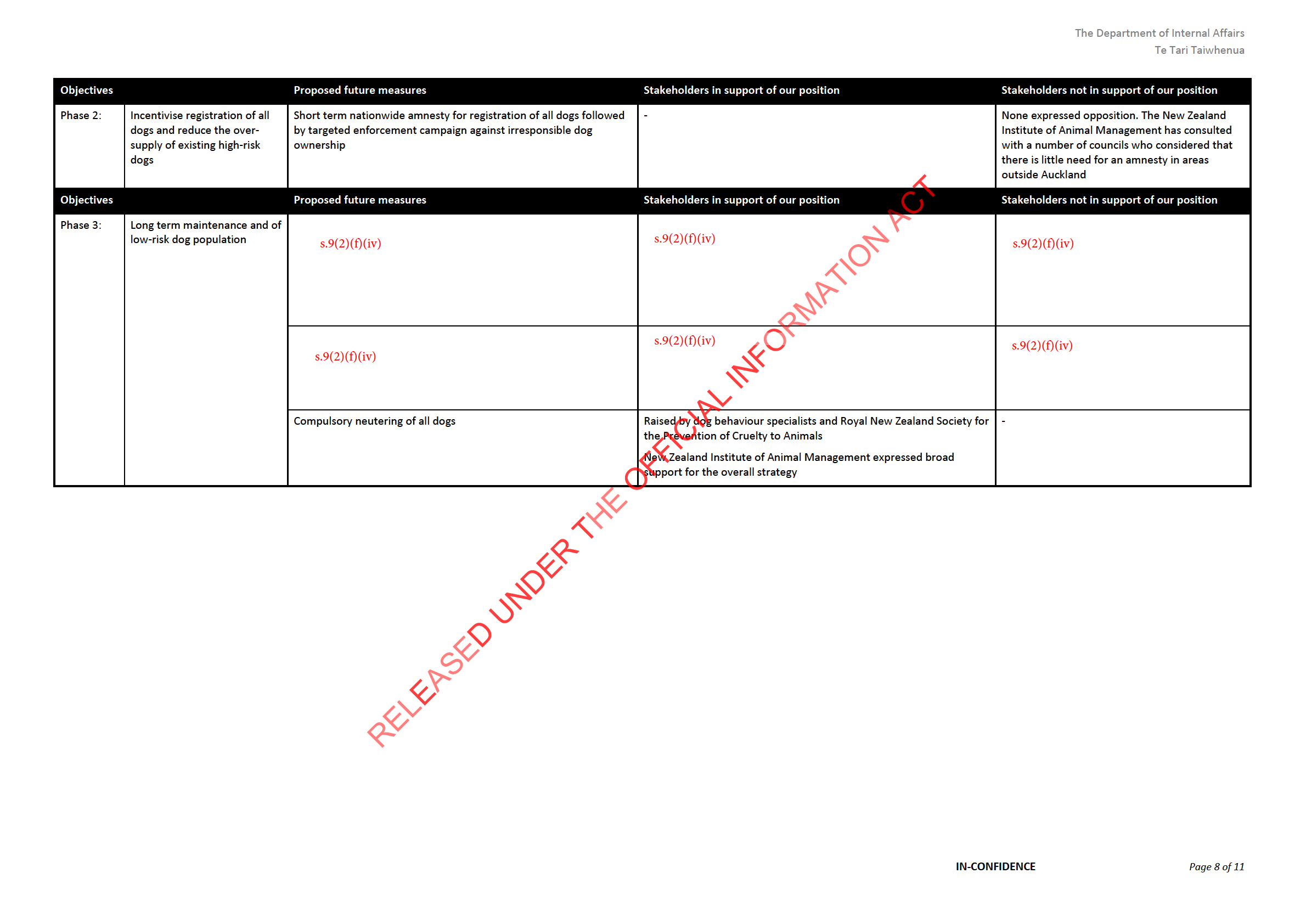

The draft Cabinet paper provides an overview of the proposed national strategy. A

CT

table of the particular options proposed and not proposed, and the level of support

ACT

across stakeholders for our position is provided in

Appendix A.

16.

A financial contribution from Government will be necessary to run an effective

subsidised neutering programme. We are working with SPCA New Zealand and

Treasury to develop costings for a national neutering program, which will be included

in the final Cabinet paper.

There is a list of potential legislative issues the stakeholder have raised that

warrant investigation

17.

In addition to the measures we seek to put in place through the Cabinet paper, there

INFO

INFORMATION

may be additional measures that will further reduce harm caused by dog attacks. At

the later stages of stakeholder engagement, some issues that we consider warrant

further investigated were raised.

18.

OFFICIAL

s.9(2)(f)(iv)

D UNDER T

E

RELEASED UNDER THE OFFICIAL

IN-CONFIDENCE

Page 4 of 11

CT

ACT

INFO

INFORMATION

OFFICIAL

D UNDER T

E

RELEASED UNDER THE OFFICIAL

The Department of Internal Affairs

Te Tari Taiwhenua

Appendix B: Draft Cabinet paper

ACT

INFORMATION

INFORMATION

RELEASED UNDER THE OFFICIAL

IN-CONFIDENCE

Page 9 of 11

The Department of Internal Affairs

Te Tari Taiwhenua

Appendix C: Draft Regulatory Impact Statement

CT

ACT

INFO

INFORMATION

OFFICIAL

D UNDER T

E

RELEASED UNDER THE OFFICIAL

IN-CONFIDENCE

Page 10 of 11

The Department of Internal Affairs

Te Tari Taiwhenua

Appendix D: Summary report of survey results and council feedback, and draft

media release

CT

ACT

INFO

INFORMATION

OFFICIAL

D UNDER T

E

RELEASED UNDER THE OFFICIAL

IN-CONFIDENCE

Page 11 of 11

Regulatory impact statement: Proposals

to amend the Dog Control Act 1996

Agency disclosure statement

ACT

This regulatory impact statement has been prepared by the Department of Internal Affairs.

It provides an analysis of the options to reduce the risk and harm from dog attacks.

Ministerial direction is to review settings with a focus on high-risk owners and high-risk dogs.

This direction limits the scope of this work and the options explored in this analysis.

There is limited data available to assess the type and extent of problems with dog control

regulation, and in particular the scale and characteristics of serious dog attacks in New

Zealand. In particular, we do not have reliable data on the actual number of dogs in New

INFORMATION

INFORMATION

Zealand.

For information about dogs in New Zealand, we are reliant on the national dog database

(NDD). Information in the NDD is based on data uploaded from individual councils, and as a

result there can be irregularities in this information from year to year. In the past not al

councils had data in the NDD for every year, so totals in the NDD will be less than the actual

number of registered dogs. Where councils do not report for a

OFFICIAL data period, an estimate is

made based on data from previous or following years. As data prior to 2013 contains a

higher degree of under-reporting most of the analysis presented here is based on data from

2013 onward.

Steve Waldegrave

General Manager, Policy

/

/

RELEASED UNDER THE

RELEASED UNDER THE OFFICIAL

IN-CONFIDENCE

IN-CONFIDENCE

Contents

Agency disclosure statement .............................................................................................1

Contents ............................................................................................................................2

Executive summary .......................................................................................................... .3 CT

ACT

Objectives ................................................................................................................. .... ..3

Criteria ............................................................................................................ ... .............3

Status quo and problem definition ............................................................ ... ....................4

Problems to be solved ........................................................................ . .. ........................... 4

The causes of dog attacks ............................................................ .... .. .............................. 5

Problem Area 1: Inherent risk associated with dogs ............... . ........................................ 6

Options and impact analysis for Problem Area 1............. .. .............................................. 7

INFORMATION

Problem Area 2: Breeder and owner behaviour ........ .....................................................

INFO

11

Options and impact analysis for Problem Area 2.. ... ...................................................... 12

Problem Area 3: Council enforcement .................. .......................................................... 14

Options and impact analysis for Problem Area 3.............................................................. 15

Problem Area 4: Lack of public knowledge of dog behaviour and high-risk dogs ............ 16

Options and impact analysis for Problem Area 4.............................................................. 17

OFFICIAL

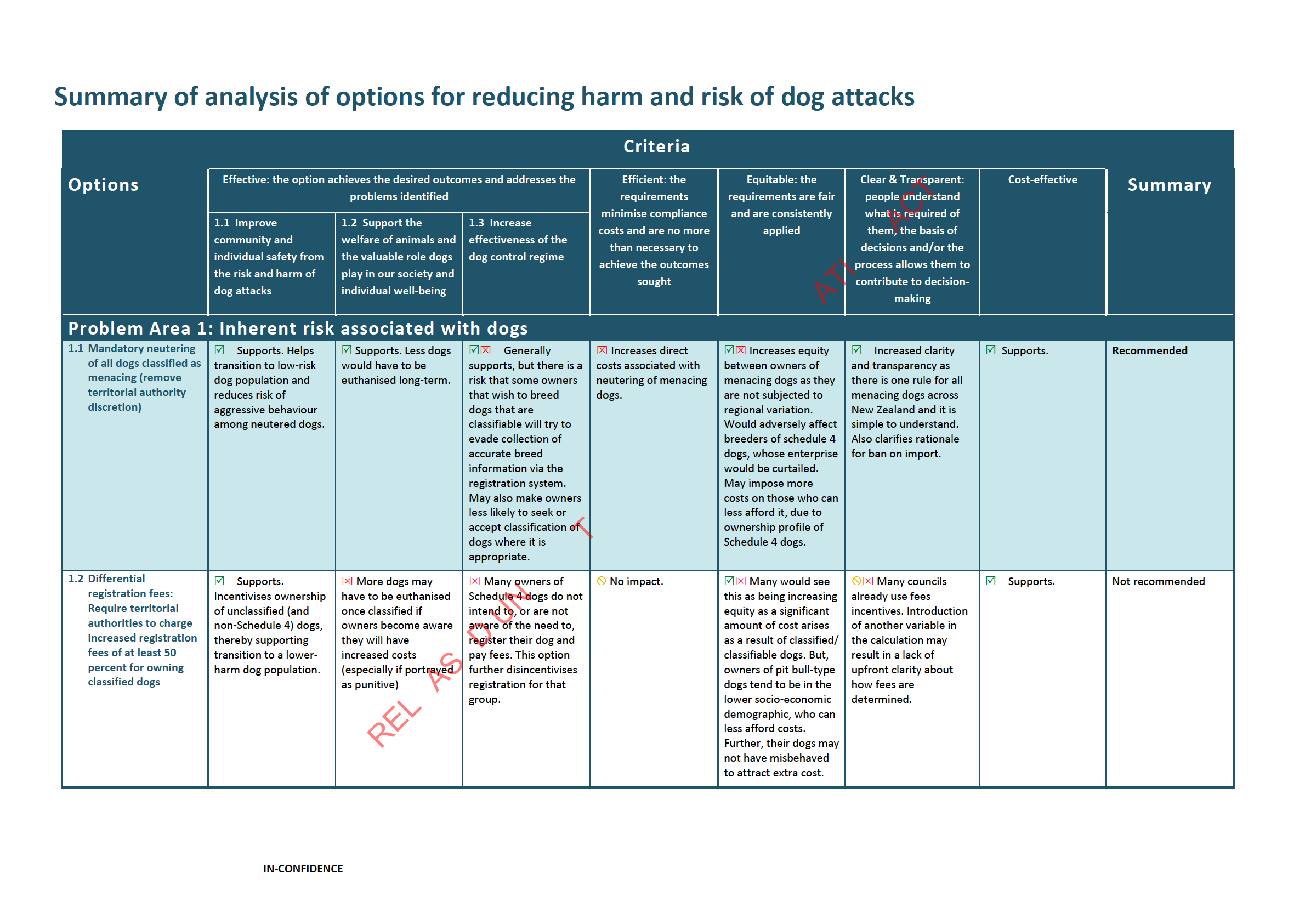

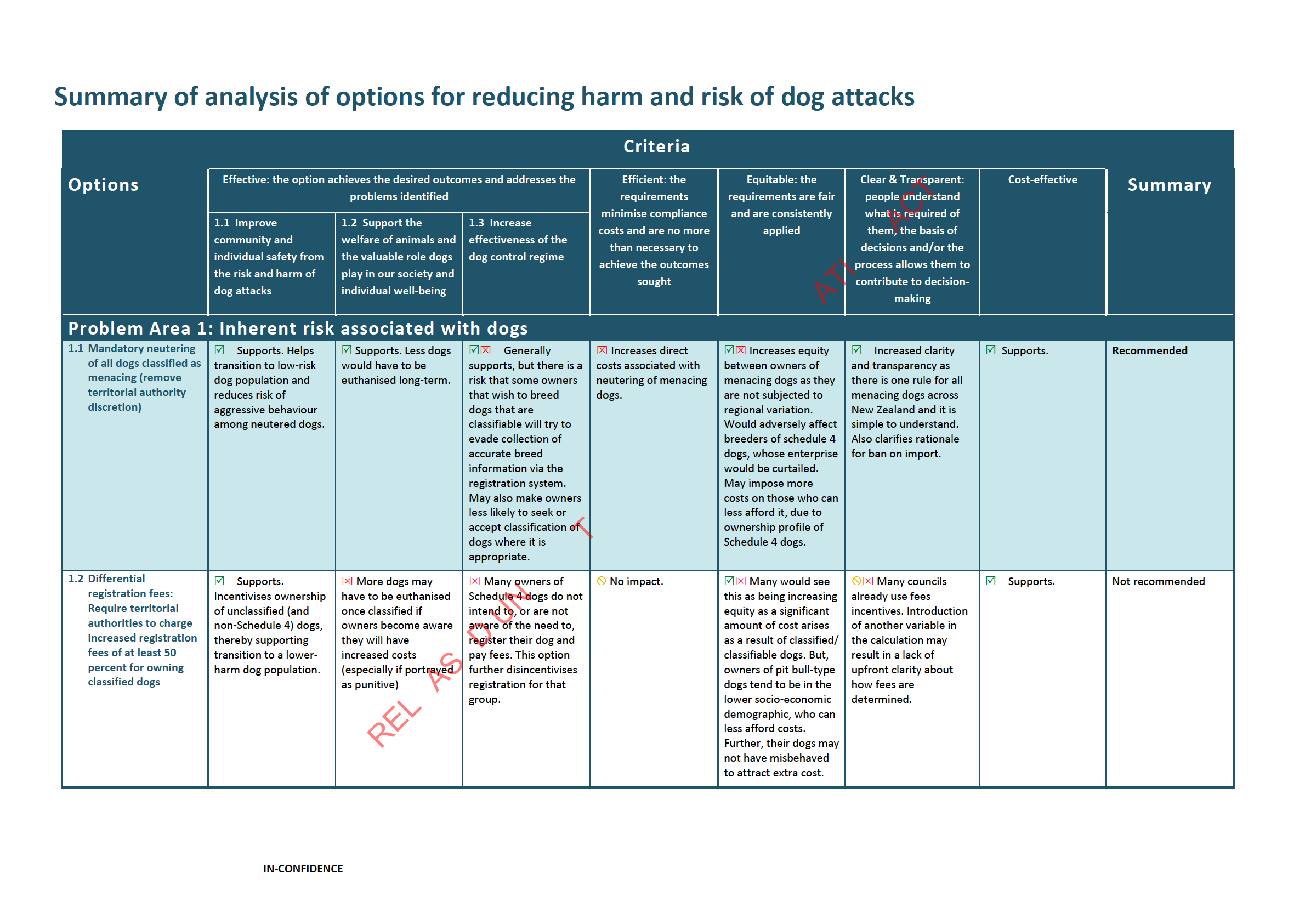

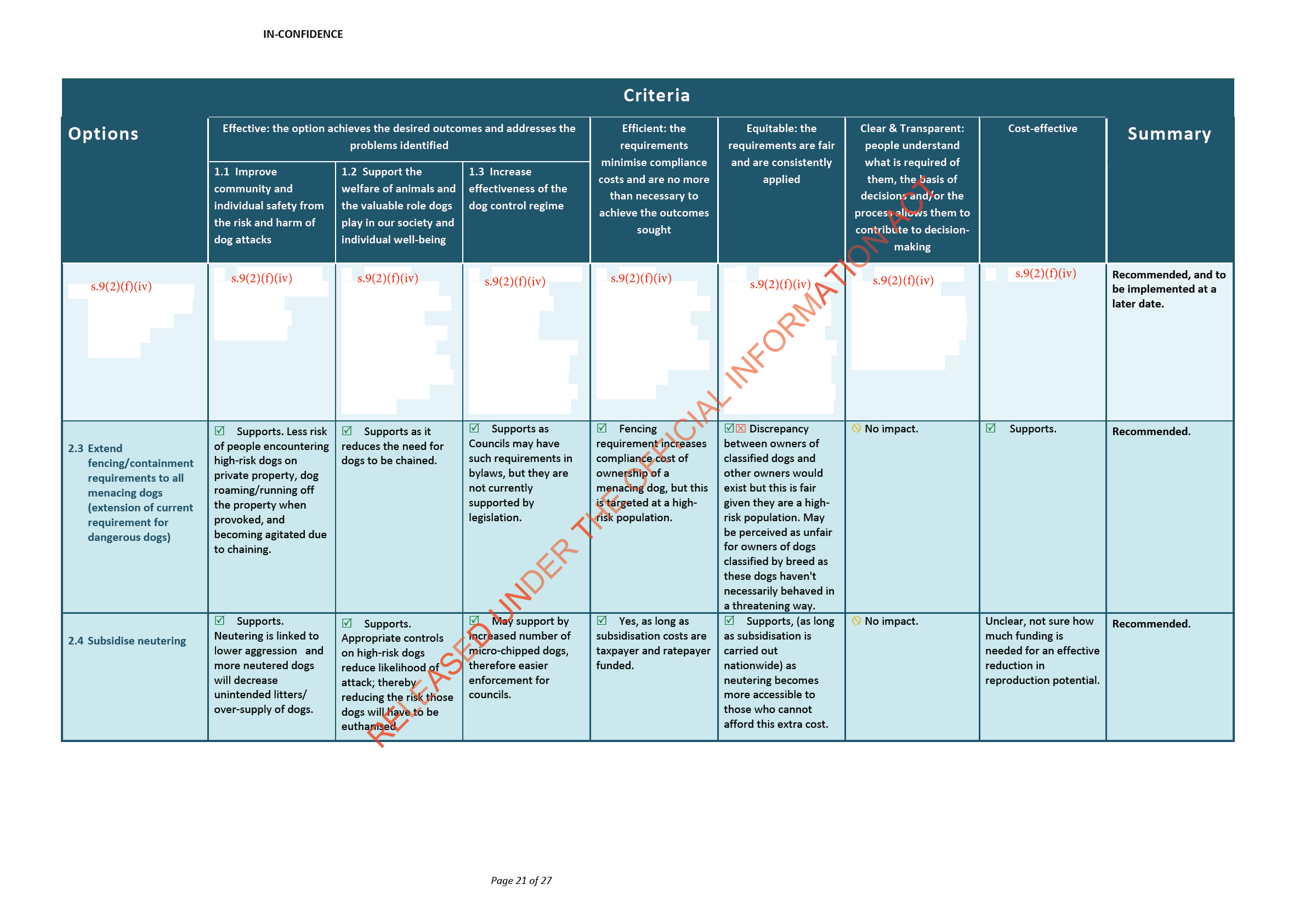

Summary of analysis of options for reducing harm and risk of dog attacks ........................ 18

Consultation ......................... .......................................................................................... 25

Conclusions and recommendations .................................................................................. 25

Implementation plan .................................................................................................... 26

Monitoring, evaluation, and review ................................................................................. 26

D UNDER T

E

RELEASED UNDER THE OFFICIAL

Page 2 of 27

IN-CONFIDENCE

Executive summary

1.

The Department has evaluated the status quo and a number of options to reduce the

risk and harm of dog attacks. The preferred options fal into four broad categories:

• Measures that transition New Zealand towards a lower risk dog population:

• Measures that encourage responsible dog ownership behaviour and discourage

negligent and reckless behaviour:

CT

• Measures that enhance the ability of territorial authorities to take effective

ACT

preventative and enforcement action against high-risk owners and high-risk dogs:

• Measures that help to protect individuals from becoming victims of dog attacks:

Requiring visual signifiers of dog classification, public education campaigns to

increase awareness of dog behaviour and safety.

Objectives

2.

The Dog Control Act 1996 aims to establish and maintain an appropr

INFO iate balance

INFORMATION

between the advantages of dog ownership to individuals and communities and the

protection of individuals and communities from dog attacks. The objectives of this

review are to further refine regulatory and non-regulatory settings to:

2.1

Improve community and individual safety from the threat and harm of dog

attacks;

OFFICIAL

2.2

Support the welfare of animals and the valuable role dogs play in our society

and individual wel -being; and

2.3

Increase effectiveness the dog control regime.

Criteria

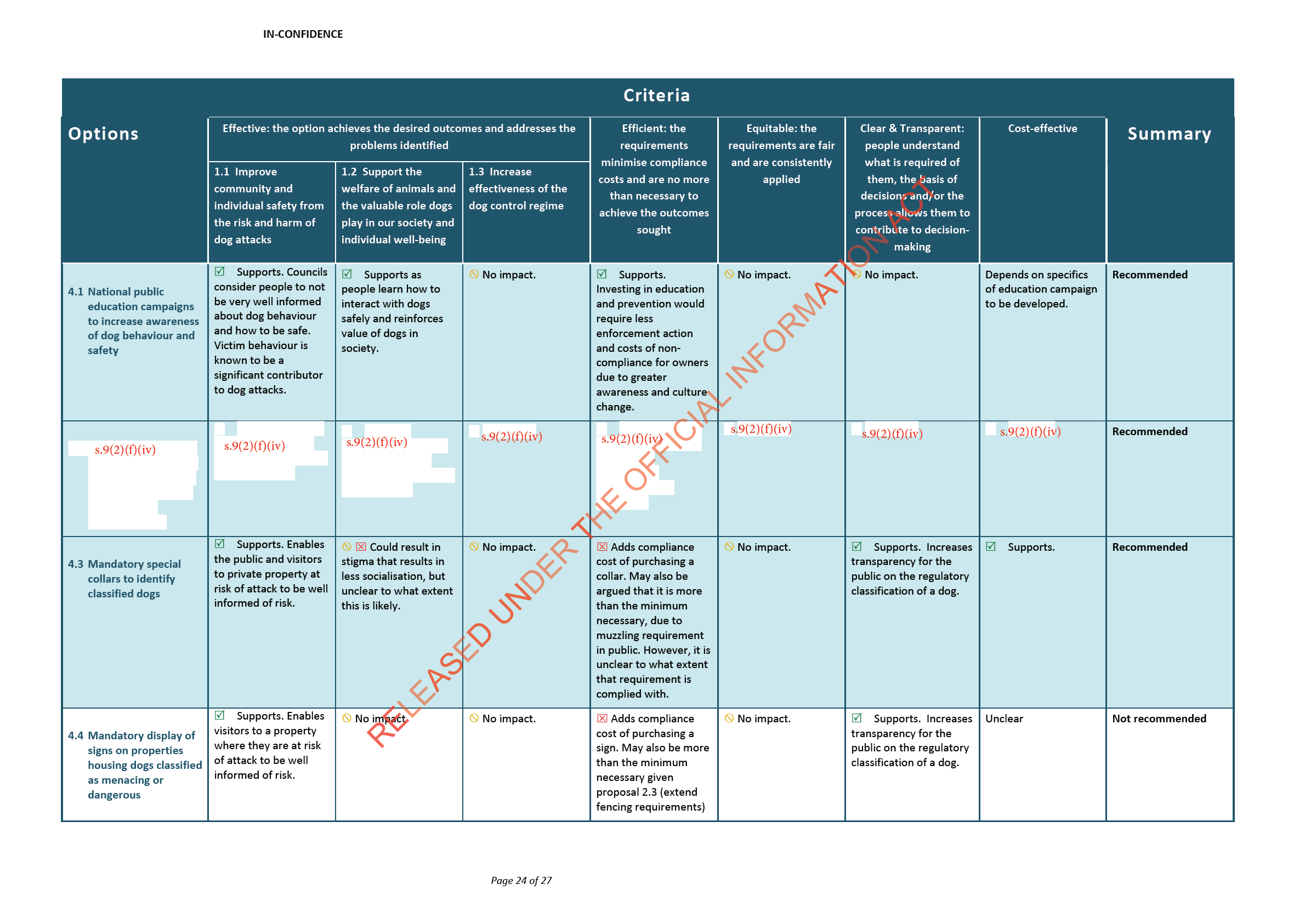

3.

The following five criteria were used when assessing options.

•

Effective: the option achieves the desired outcomes and addresses the problems

D UNDER T

identified;

•

Efficient: the requirements minimise compliance costs and are no more than

necessary to achieve the outcomes sought;

E•

Equitable: the requirements are fair and are consistently applied; and

•

Clear and Transparent: people understand what is required of them and the basis

RELEASED UNDER THE OFFICIAL

of decisions.

•

Cost-effective: the option is a cost-effective expenditure of public funds

Page 3 of 27

IN-CONFIDENCE

Status quo and problem definition

4.

Any interaction between dogs and humans involves some risk. The central objective of

dog control policy in New Zealand is to strike an appropriate balance between the

advantages to individuals and communities of dog ownership and the protection of

individuals and communities from dog attacks.

5.

Dog control is regulated by the Dog Control Act 1996 (the Act). The Act was introduced

after a review of dog control in the mid-1990s which found that a serious dog control

CT

problem existed in New Zealand. The Act was amended substantially in 2003, and has ACT

been amended three times since then. The Act is implemented by city and district

councils with the support of their communities. The Act places increased restrictions

dogs according to characteristics typically associated with a particular breed or type, or

because of observed or reported behaviour.

6.

The Government is reviewing the policy settings around dog control to determine if

central and local government can do more to improve public safety around dogs. The

review aims to address concerns that serious dog attacks continue to happen with long

lasting impacts for victims and families. Serious dog attacks can be defined as an

interaction with a dog which results in death or serious injury (i.e. requiring

INFO

INFORMATION

emergency/hospital treatment) or which has the potential for such.

7.

There is limited data available to assess the nature and extent of problems with dog

control regulation, and in particular the scale and characteristics of serious dog attacks

in New Zealand. Available high-level evidence is as follows.

Problems to be solved

OFFICIAL

The rate of hospitalisation due to dog bites and number of ACC claims for dog-related

injury have been increasing significantly more than the number of registered dogs

8.

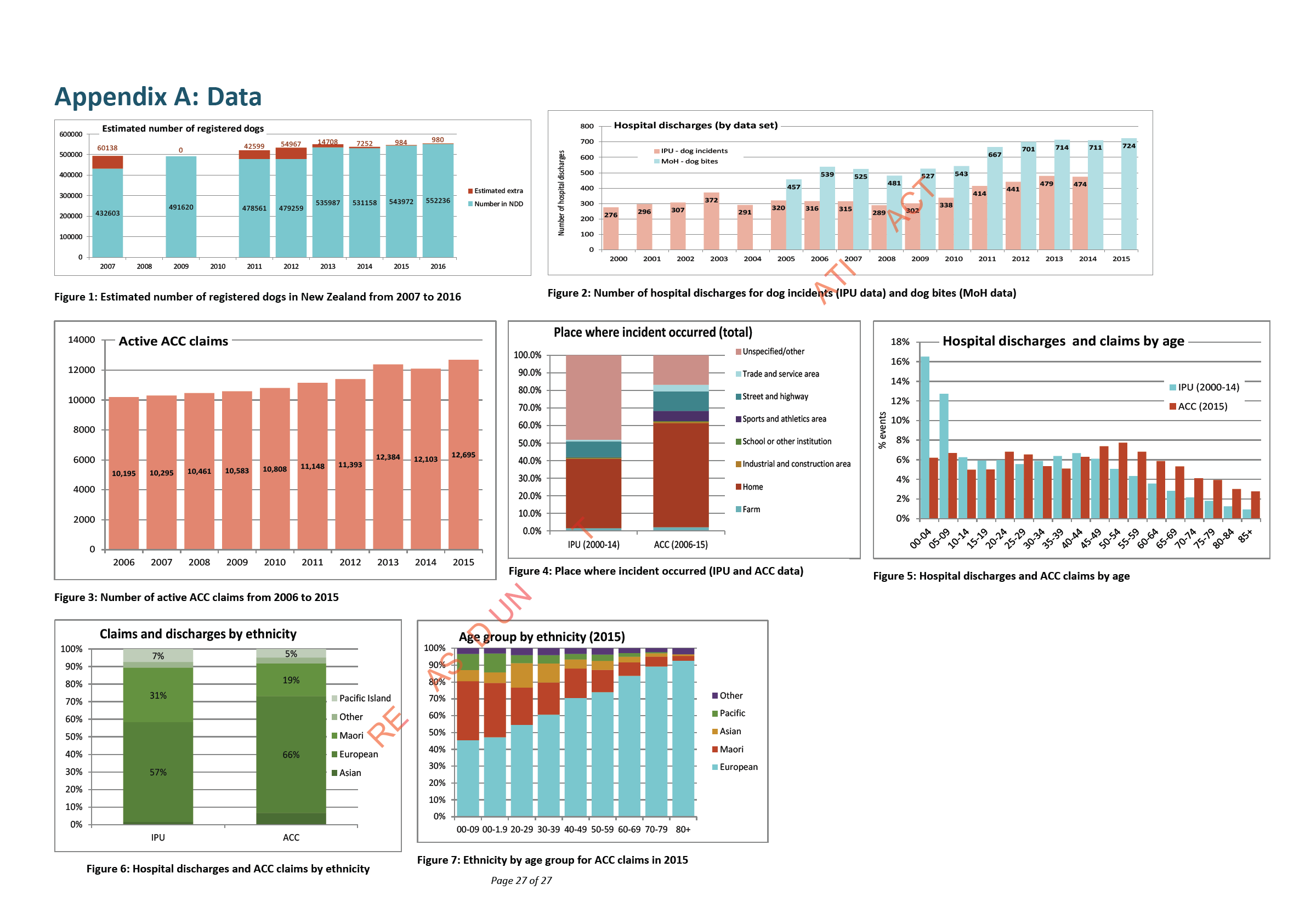

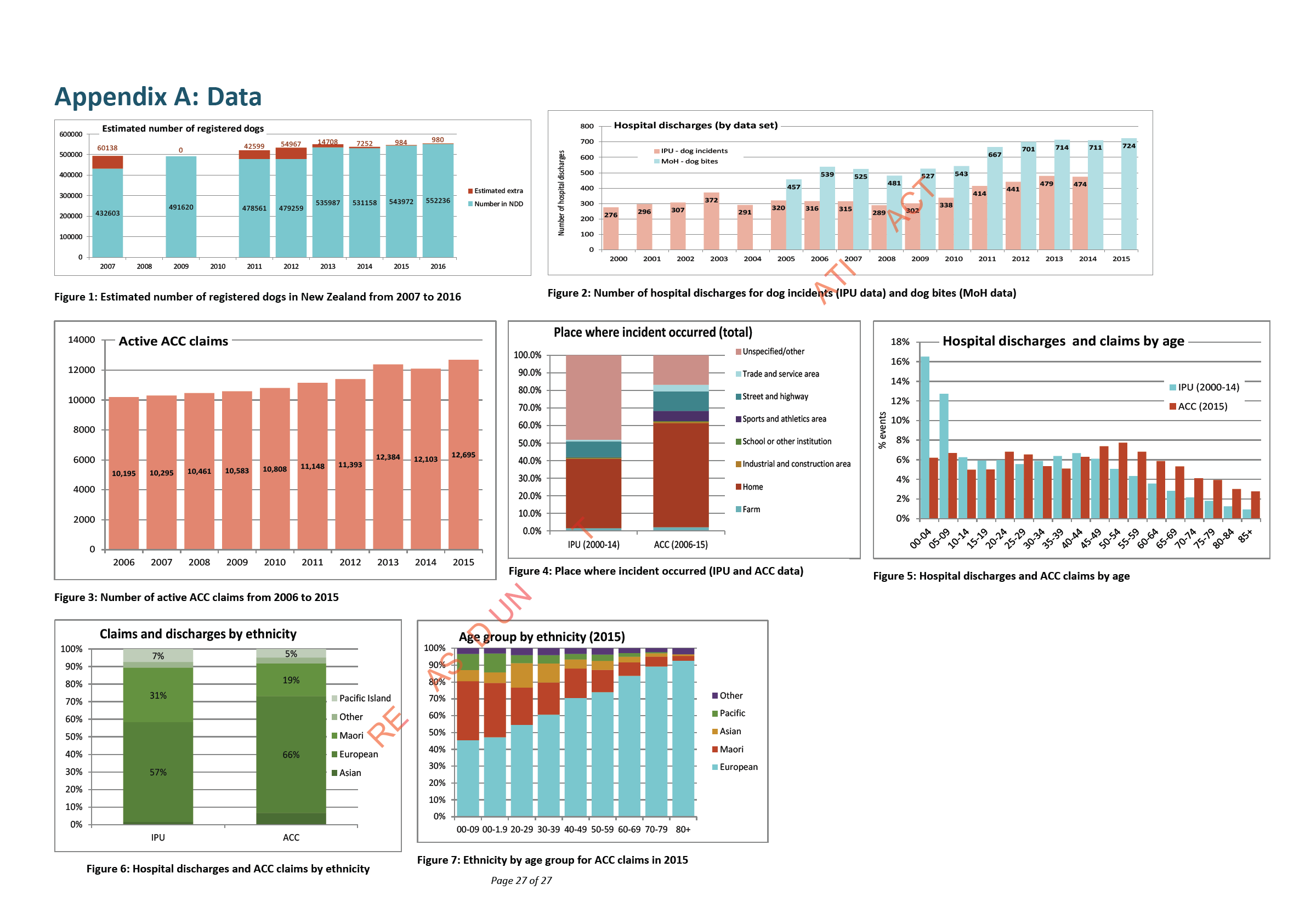

The number of registered dogs in New Zealand has been increasing slightly over the

past decade.

1 There were an estimated 492,741 registered dogs in 2007, and in 2016

there are an estimated 533,216 registered dogs

(Figure ). Over the last few years the

number of registered dogs per capita has remained stable, at about 12 dogs per 100

people. D UNDER T

9.

Ministry of Health data shows that the number of discharges for dog

bites has

increased by 53 percent from 457 in 2005 to 724 in 2015 (Figure 2). The rate of

hospitalisations by population is also increasing, with a rate of 15.8 hospitalisations per

E100,000 people in 2015. The annual rate of change is variable with discharges in the

last three years showing little change.

RELEASED UNDER THE OFFICIAL

1 The National Dogs database provides information on the number of registered dogs by councils. However,

prior to 2013 not al councils supplied data for every year. In addition, the number of registered dogs does not

reflect the total dog population in New Zealand.

Page 4 of 27

IN-CONFIDENCE

10. Otago University’s Injury Prevention Unit’s data shows that the number of

hospitalisations for

dog-related incidents increased by 72 percent from 276 in 2000 to

474 in 2014 (Figure 2).

2 Both the IPU and MoH data show a significant increase in

discharges in 2011, and a slowing/reduction in the rate of growth of hospitalisations

over the last few years.

11. ACC data on dog-related injury claims shows a 25 percent increase in the number of

active claims from 10,196 in 2006 to 12,695 in 2015 (Figure 3).

3 The total pay-out for

dog-related injuries from 2006 to 2015 was $34.860 mil ion. In 2015, the average cost CT

per claim was $407, and while there has been more annual variation in the average ACT

cost per claim than for the number of active claims, the cost of the average claim still

increased by 72 percent from 2006 to 2015.

Most dog incidents occur in the home; children are disproportionately involved in serious

dog attacks

12. Both ACC claim and hospitalisation data show that most dog-related injuries and

incidents occur in the home, fol owed by those that occur on the street (Figure 4). This

finding is supported by findings overseas.

4

13. According to the IPU data, just under 30 percent of the patients discharged were under

INFO

INFORMATION

the age of 10. In contrast the ACC claims data shows the peak rate of claims is for

clients in the 50-54 age range (Figure 5). This suggests that while more people may

claim for ACC injuries requiring treatment at older ages, the impact of dog-related

injuries appears to be greater on younger people. An analysis of media reports of

severe dog attacks supports the view that children were disproportionately involved in

serious incidents. Fifty-nine dog attack incidents involving 68 people injured were

OFFICIAL

reported on by the media over the last five years.

5 A third of the people injured were

under the age of nine.

14. Māori also appear to be a particularly affected group, as they tend to make up a higher

proportion of ACC claimants and hospitalisations than their percentage of the total

population (Figure 6). This is particularly evident for younger age groups (Figure 7).

The causes of dog attacks

15. The causes of dog attacks are known to be multifactorial. Literature identifies five key

interacting factors as determina

D UNDER T nts of the tendency of a dog to bite, namely:

• heredity (genes, breed),

• early experience,

E• socialisation and training,

• health (physical and psychological), and

RELEASED UNDER THE OFFICIAL

2 IPU analysis also originates from data col ected and supplied by MoH. But as wel as being subject to other

selection criteria, IPU data excludes day patients. Hence, the much lower numbers than for MoH data

presented here.

3 It should be noted that the ACC claims data is for dog related injuries and includes more than just ‘attacks’ or

‘bites’.

4 Australian Veterinary Association

“Dangerous dogs – a sensible solution: Policy and model legislative

framework” (August 2012).

5 275 media articles on dog attacks were examined from 2011 to 2016.

Page 5 of 27

IN-CONFIDENCE

•

victim behaviour.

16. Other factors include the sex and age of the animal, along with a range of other social

and environmental factors. International research findings are that:

•

Male dogs are 6.2 times more likely to bite than females

•

Undesexed dogs are 2.6 times more likely to bite than those that are neutered

•

Chained dogs are 2.8 times more likely to bite than unchained dogs

•

Dogs with “dominance aggression” are more likely to be 18-24 months old

CT

ACT

•

Dogs bred at home are less likely to bite, compared to those obtained from

breeders and pet shops

•

Dogs are more likely to bite the older they are when they are obtained

•

Biting dogs are more likely to live in areas of lower median income

•

Dogs are more dangerous when acting as a pack

17. There is no single contributing factor underlying al dog attacks. As such reducing the

risk and harm of attacks warrants action to address all of the five key factors described

above. In the absence of government intervention, the number and severity of dog

attacks is likely to continue. At the broadest level of analysis there are four main

INFO

INFORMATION

problem areas that have been identified with respect to dog control. These are

discussed below.

Problem Area 1: Inherent risk associated with dogs

18. The acceptance of dogs in our society means a baseline level of risk. However, a higher

level of risk arises due (i) intrinsic risk variation in the dog

OFFICIAL population owing to the

predispositions of particular breeds and (ii) the variation in potential for harm should a

dog attack, owing to the size of the dog.

Status quo

19. Councils have powers and responsibilities to declare a dog menacing or dangerous in

certain circumstances. Councils

may classify a dog as menacing dogs if it believes the

dog poses a threat to public safety because of its behaviour. Councils

must classify a

dog as menacing if there are reasonable grounds to believe it belongs wholly or

D UNDER T

predominantly to one or more of the breeds or types of dog that it is il egal to import

into New Zealand (under Schedule 4 of the Act). Currently these 'banned' breeds are

American Pit Bull Terrier, Dogo Argentino, Brazilian Fila, Japanese Tosa and Perro de

Presa Canario. Other breeds or types of dogs can be added to the list of restricted dogs

Eby Order in Council. Increased restrictions placed on dogs classified as menacing

include mandatory muzzling when in public, and councils

may require them to be

neutered.

RELEASED UNDER THE OFFICIAL

20. Dangerous dogs include those where an owner is convicted of an offence under 57A of

the Act, or where, on the basis of sworn evidence, the council believes a dog is a threat

to public safety or where the owner records in writing that it is a threat to public

safety. Dangerous dogs must be kept in a fenced part of the owner's property,

must be

muzzled, on a leash in public and neutered.

Page 6 of 27

IN-CONFIDENCE

21. The NDD records the number of registered dogs classified as menacing and as

dangerous under the Dog Control Act 1996. Since 2013 the number of menacing dogs

has steadily increased by six percent. The number of dogs classified as dangerous has

increased by two percent over the same period, although the rate of annual change is

more variable. The percentage of menacing and dangerous dogs in the total

population of registered dogs has remained at 1.6 percent for the last four years.

22. International experience has shown that breed-specific approaches has not been

successful in reducing dog attacks, and the trend observed is a move away from this

approach. Reasons why it is not successful include:

ACT

•

Breed alone is not an effective indicator or predictor of aggression in dogs and

focussing on particular breeds fuels the misperception that other dogs won’t bite.

•

It is not possible to precisely determine the breed of the types of dogs targeted by

breed-specific legislation by visual identification or by DNA analys s ATI

•

Breed-specific legislation ignores the human element whereby dog owners who

desire this kind of dog will simply substitute another breed of dog of similar size,

strength and perception of aggressive tendencies.

Pit bull-type dogs are over-represented in impounds, attacks, prosecutions, and euthanasi

INFORMATION

a

rates

23. While a number of the breeds in Schedule 4 are not known to exist in New Zealand,

there is anecdotal evidence that some have been imported undeclared and are

established here. With respect to the pit bul type dogs, councils’ evidence is that they

have increased greatly in number around the country. In the South Auckland region,

for the 2014/15 year, 37 percent of total impounds were considered Pit bull types and

crosses. Because of Auckland Council’s no rehoming policy for classified dogs as large

number of dogs are euthanised. Pit bull type dogs have been bred to eliminate

submission inhibition. As such, even if an individual pit bull type dog does not have

T

aggressive tendencies it has a latent potential for significant harm should an incident

arise where the dog becomes stressed/agitated.

Options and impact analysis for Problem Area 1

Mandatory neutering of al dogs classified as menacing (remove territorial authority

D UN

discretion)

24. At present, the territorial authorities have discretion as to whether they require the

AS

owner of a dog classified as menacing to neuter the dog. Approximately two-thirds of

councils have adopted mandatory neutering. Where such a policy is adopted, a non-

compliant owner can be fined (upon conviction) and the territorial authority can seize

RE the dog and retain it until the owner is willing to comply

RELEASED UNDER THE OFFICIAL, or dispose of the dog.

25. For dogs classified menacing

by breed, the import of such dogs is already banned. So

there is a clear rationale to require mandatory neutering. In fact, variation is this

respect undermines the current regime intent of restricting Schedule 4 breeds and

types to restrict these breeds in New Zealand. For dogs classified menacing

by deed,

neutering is understood to have behavioural advantages.

Page 7 of 27

IN-CONFIDENCE

26. As such, there is no need for council variation on this matter and national consistency

is desirable. Mandatory neutering would reduce the risk that the dog will commit a

serious attack; it wil also drive consistent practice across the country, and reduce costs

for territorial authorities (by streamlining and simplifying the process). Neutering also

supports animal welfare considerations as lowered aggression results in reduced risk

of the dog attacking and having to be euthanised.

27. Overal mandatory neutering would enhance the effectiveness of the dog control

regime, but there is a risk that some owners that wish to breed dogs that are

classifiable menacing or dangerous will try to evade collection of accurate breed

ACT

information via the registration system. It may also increase costs for councils if

owners become less likely to seek or accept classification of dogs where it is

appropriate.

28. This option increases equity between owners of menacing dogs as they are not

ATI

subjected to regional variation and there is 'one rule for all'. However, dogs that are

classifiable menacing by breed tend to be owned by those in lower socio-economic

groups. As such, in practice it may impose more costs on those who can less afford it.

29. This option is recommended as it meets objectives better than the status quo and is

cost-effective overall.

INFORMATION

Differential registration fee: Require territorial authorities to charge increased registration

fees of at least 50 percent for owning classified dogs

30. Differential fees are one tool for the creation of the right incentives among dog

owners. This option would seek to disincentivise ownership of dogs classified

menacing or dangerous, with the aim of transitioning to a lower-risk dog population,

with a lower potential for harm inflicted in the event of an attack.

31. To a certain extent, this option disincentivises ownership of classified (and Schedule 4)

dogs, thereby supporting trans

Tition to a lower-harm dog population. However, many

owners of Schedule 4 dogs do not intend to, or are not aware of the need to, register

their dog and pay fees. This option further disincentivises registration for that group.

Once those dog owners are identified, they are less likely to be able to register their

dog on the spot Therefore more dogs may have to be euthanised if owners become

aware they will have increased costs (especially if portrayed as punitive).

32. Many would see thi

D UN s option increasing equity as a significant amount of cost arises as a

result of classified/ classifiable dogs. But, owners of pit bul -type dogs tend to be in the

lower socio-economic demographic, who can less afford extra costs and may lose their

AS

dogs as a result. Further, their dogs may not have even exhibited aggressive

tendencies to attract extra cost. This option is not recommended.

D

RE

ifferential registration fees: Require territorial authorities to

RELEASED UNDER THE OFFICIAL

charge reduced/equal

registration fees for owning classified dogs

33. To be completed

Page 8 of 27

IN-CONFIDENCE

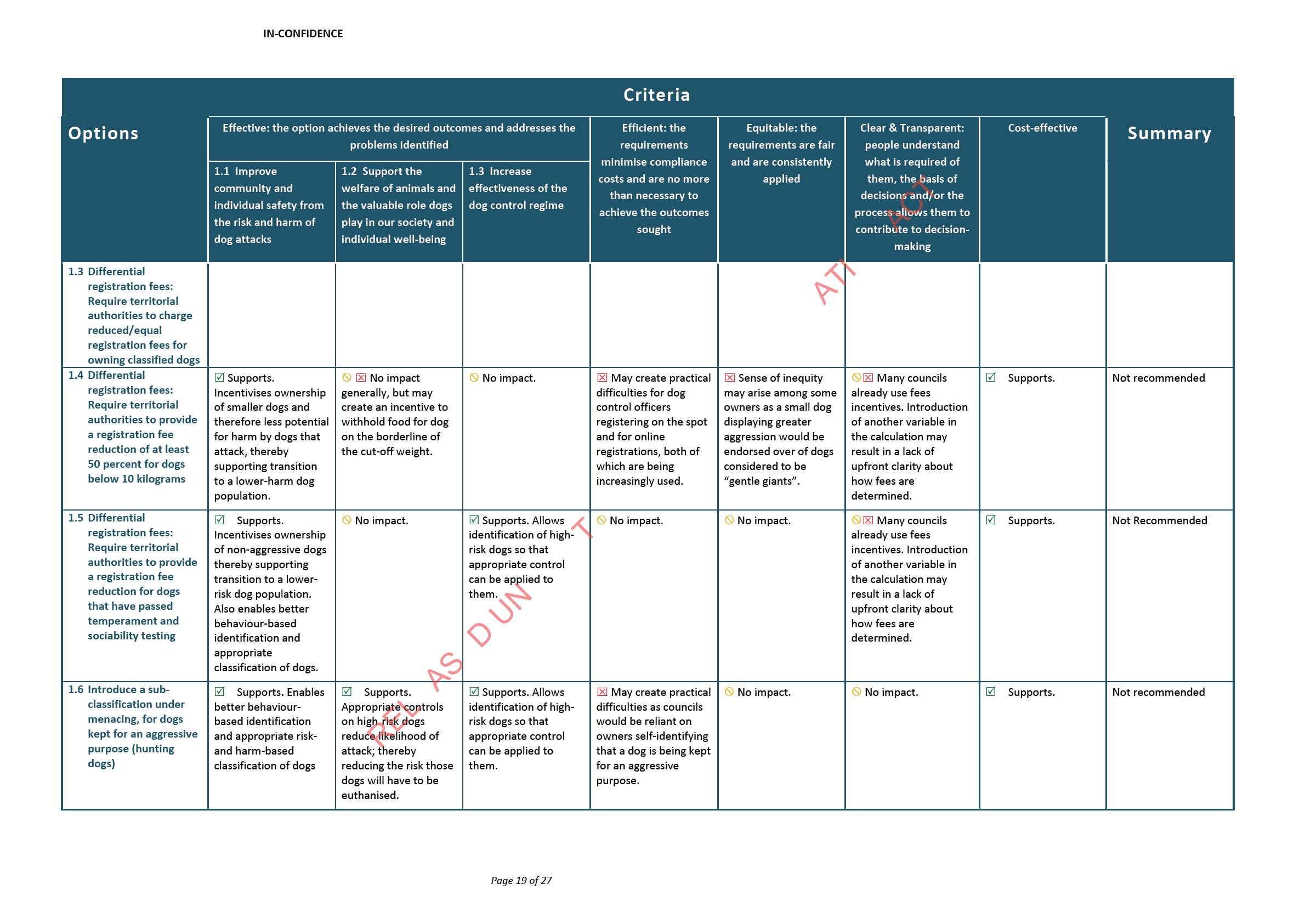

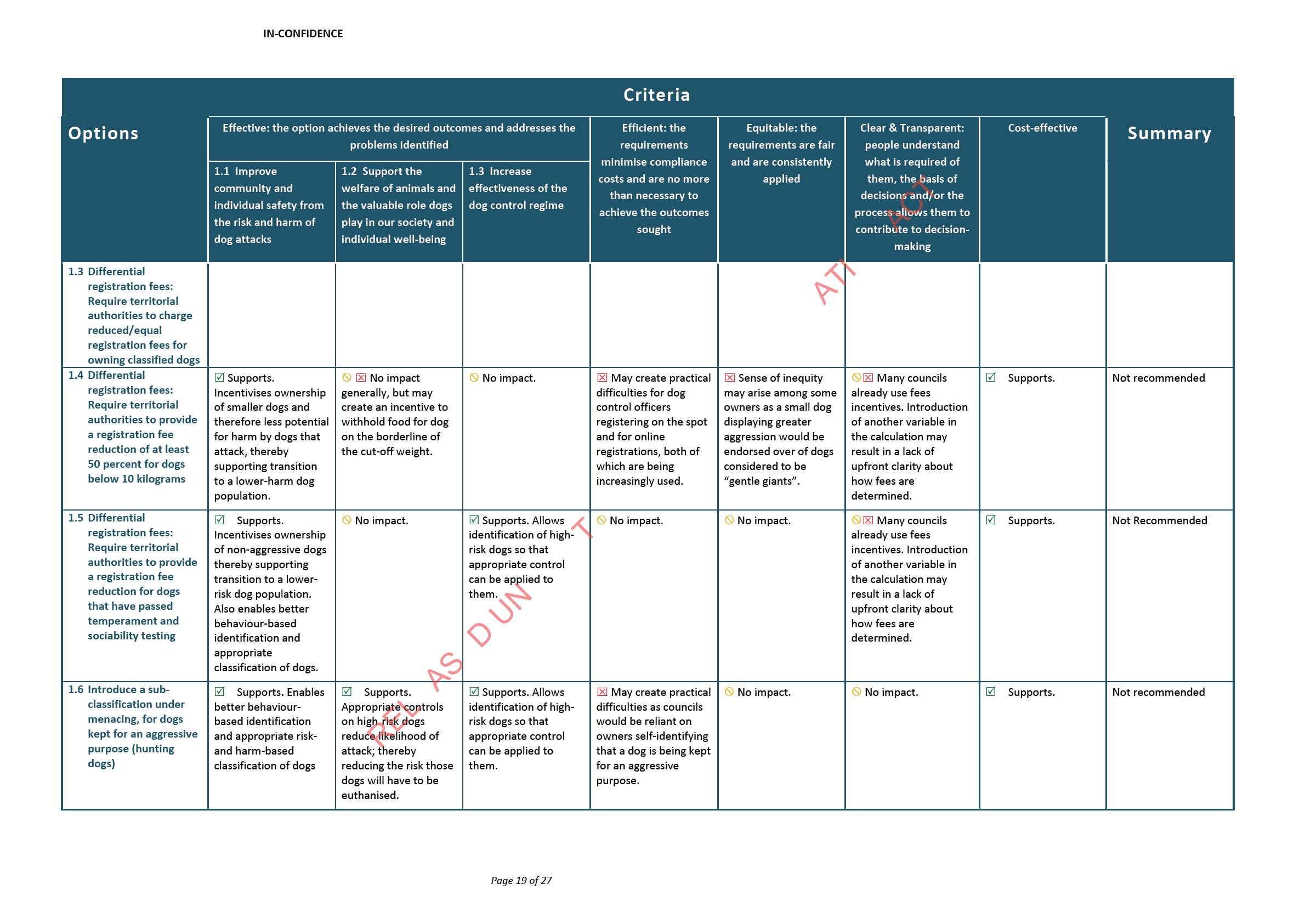

Differential registration fee: Require territorial authorities to provide a registration fee

reduction of at least 50 percent for dogs below 10 kilograms

34. As discussed in the option above, differential fees are a tool for the creation of the

right incentives among dog owners. Although al dogs/breed types and have aggressive

tendencies, the size of a dog plays a significant role in the potential harm that can be

inflicted. This option would seek to incentivise ownership of smaller sized dogs, with

the aim of transitioning to a lower-risk dog population, with a lower potential for harm

inflicted in the event of an attack.

35. This option incentivises ownership of smaller sized dogs, which have less potential for ACT

harm when an attack takes place, thereby supporting transition to a lower-harm dog

population. There are generally no animal welfare impacts, but may create an

incentive to withhold food for dog on the boundaries of the cut-off weight. There are

likely to be practical difficulties with this approach; dog control officers are often

ATI

registering unregistered dogs on the spot when they are identified. This approach

would potentially require them to carry scales. Also more councils are moving towards

online registrations, and such information is not able to be verified. There are already

inaccuracy issues with self-identified information in the system, such as breed of dog.

As this approach aims to reduce potential for harm but not aggressive tendencies, a

sense of inequity may also arise among some owners as a small dog displaying greate

INFORMATIONr

aggression would be endorsed over of dogs considered to be “gentle giants”.

36. It is also important to note that many councils already use fees incentives. Introduction

of another variable in the calculation may result in a lack of upfront clarity about how

fees are determined. The measure would however, be cost-effective.

37. This option is not recommended.

Differential registration fee: Require territorial authorities to provide a registration fee

reduction of at least 50 percent for dogs that have passed temperament and sociability

T

testing

38. As discussed in the options above, differential fees are a tool for the creation of the

right incentives among dog owners. This option would seek to incentivise ownership of

dogs with a lower individual risk profile, with the aim of transitioning to a lower-risk

dog population. Once temperament tested, councils could require repeat test as

appropriate (e.g. every three years), or once tested, the fees reduction may be

D UN

retained as a result of no complaints and infringements being registered against the

dog and their owner.

AS

39

This option incentivises ownership of non-aggressive dogs thereby supporting

transition to a lower-risk dog population. Also enables better behaviour-based

identification and appropriate classification of dogs. It is also considered to support

animal welfare considerations as it allows identification of high-risk dogs so that

RE

RELEASED UNDER THE OFFICIAL

appropriate care and control can be applied to them.

Page 9 of 27

IN-CONFIDENCE

40. It is important to note that many councils already use fees incentives. Introduction of

another variable in the calculation may result in a lack of upfront clarity about how

fees are determined. The measure would be cost-effective long term. However,

temperament is a new and evolving area requiring a level of training and expertise.

Testers/behaviourist used would need to be approved. Should this option be

progressed, there is likely to be a need to invest in training across New Zealand to build

up the skil -set. As such, appropriate lead-in time should be provided for councils to

implement such a policy.

41. This option is not recommended.

ACT

Introduce a sub-classification under menacing for dogs kept for an aggressive purpose

(hunting dogs)

42. Currently dogs can be classified as menacing by breed (section 33C) and by deed

ATI

(section 33E). An additional appropriate menacing classification for dogs may be as

menacing by purpose, for hunting dogs. These dogs are not only expected to have

aggressive tendencies, they will be selected by their owner as a dog able to inflict

significant harm. This option enables better behaviour-based identification and

appropriate risk-and harm-based classification of dogs INFORMATION

43. There is no New Zealand data on the extent to which dog attacks in New Zealand are

caused by hunting dogs, but it is appropriate that a higher-risk classification applies to

them in light of their purpose.

44. There may be practical difficulties as councils would be reliant on owners self-

identifying that a dog is being kept for an aggressive purpose.

45. This option is not recommended.

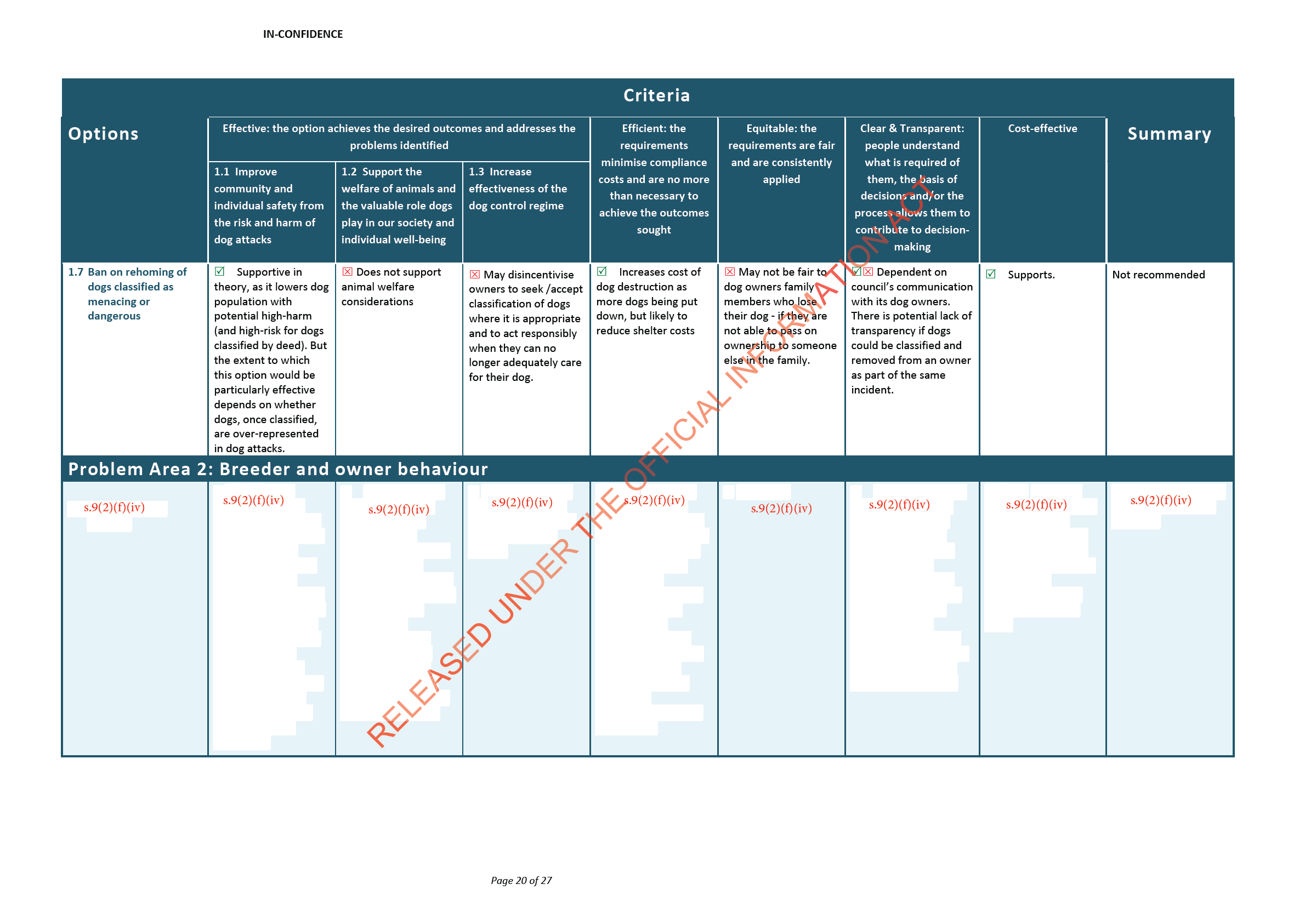

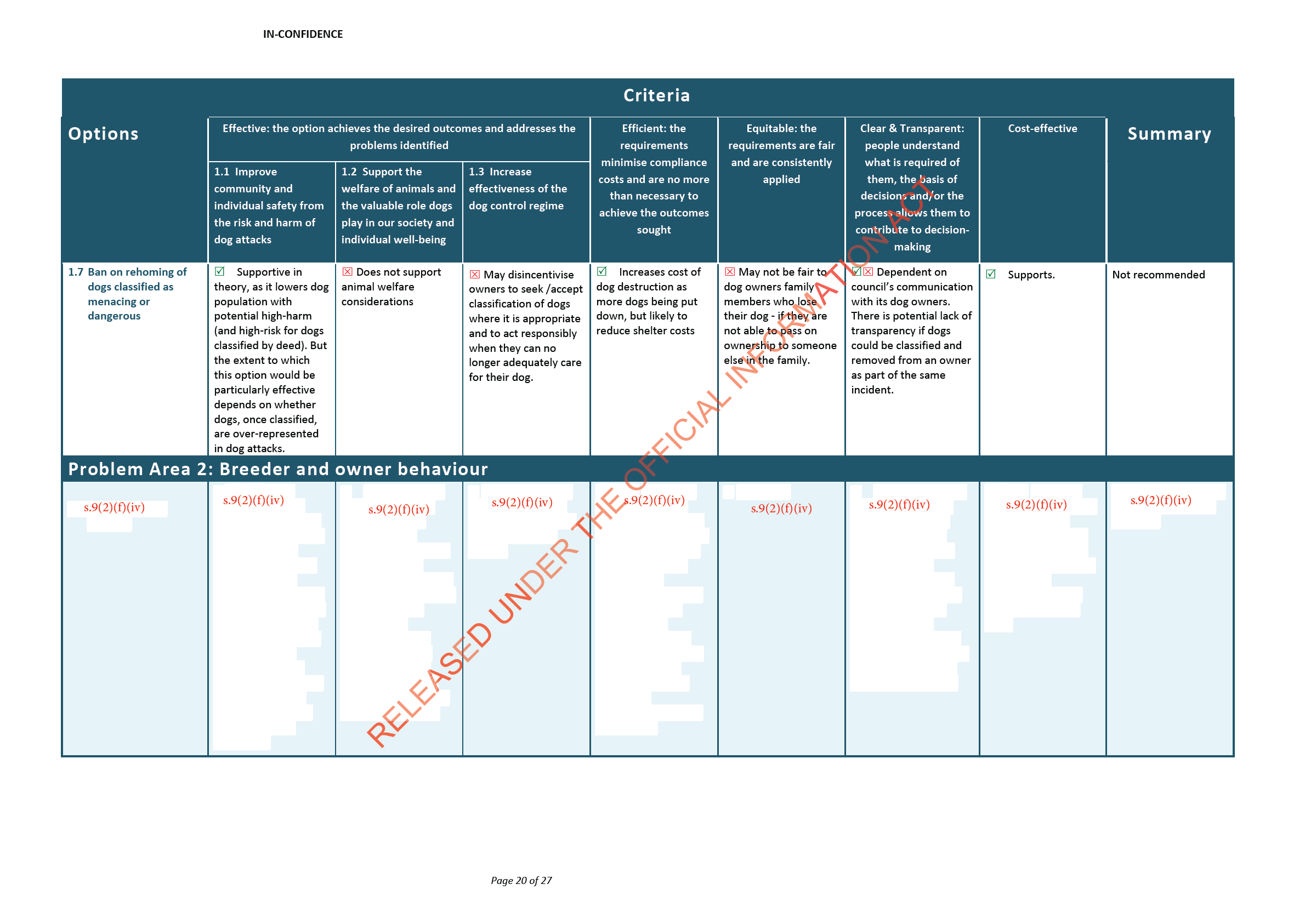

Ban on rehoming of dogs classified as menacing or dangerous

T

46. Currently many councils have a policy of the rehoming of dogs classified menacing or

dangerous from their council shelters. This option would make that rule consistent

across all councils and also prevent the SPCA from rehoming those dogs.

47. This is supportive in theory, as it lowers dog population with potential high-harm (and

high-risk for dogs classified by deed). But the extent to which this option would be

particularly effective depends on whether dogs, once classified and rehomed, are over-

D UN

represented in dog attacks. There is no data on this. It does not support animal welfare

considerations, particularly where a dog maybe well-adjusted and non-aggressive, but

classified by breed due to its potential for significant harm should there be an attack.

AS

Such a ban may disincentivise owners to seek or accept classification of dogs where it

is appropriate and to act responsibly when they can no longer adequately care for

their dog. People will also be less likely to surrender dogs to the council if there was

RE

RELEASED UNDER THE OFFICIAL

such a ban.

48. The option is however, likely to reduce shelter costs and be cost-effective.

49. This option is not recommended, as this is an area where local communities are best

placed to decide what is most appropriate for their context.

Page 10 of 27

IN-CONFIDENCE

Problem Area 2: Breeder and owner behaviour

50. As three of the five key factors in dog aggression involve a dog’s environment,

6

breeders and owners are crucial determinants of the risk associated with the dog. As

such, ingraining responsible attitudes to dog ownership is an important area of action.

Measures are needed to encourage responsible dog ownership and discourage

negligent and reckless behaviour through a combination of removing unnecessary

hurdles, providing incentives, and ensuring strong penalties.

ACT

Status quo

51. Dog owners have a number of obligations under the Dog Control Act 1996. These

include registering their dog with the local council before it is three months old or

when the owner receives the dog, and micro-chipping their dog when it is registered

ATI

for the first time (except for farm dogs), or if it has been classified as dangerous or

menacing.

52. Dog owners must also make sure the dog does not scare or injure any person or any

other animal and is kept under control at all times; and care for their dog – exercise it

and provide food, water and shelter.

INFORMATION

53. A dog owner must take al reasonable steps to ensure that the dog does not:

•

cause any nuisance to any other person, for example by constant barking, howling

or roaming

•

injure, endanger or cause distress to any stock, poultry, domestic animal or

protected wildlife

•

damage or endanger any property belonging to another person.

54. The penalty for owning a dog involved in an attack causing serious injury is up to three

years’ imprisonment and/or a fine of up to $20,000. The penalty for not registering a

T

dog is $300 as it the penalty for not micro-chipping a dog if required to do so.

55. There were 415,144 registered dog owners in New Zealand in 2016. This number has

increased by 7 percent since 2013. At the same time, the number of dogs per owner

has decreased by around 7 percent. This suggests that while more people are owning

dogs (and the total number of dogs has increased very slightly), people are tending to

own fewer animals.

D UN

56. Evidence from councils and animal management officers is that irresponsible dog

ownership is largely down (i) a lack of owner education about dog behaviour and how

to be

ASresponsible (ii) socio-economic factors resulting in an inability to meet extra

costs associated with responsible ownership, and (iii) unwilling non-compliant

attitudes among members of society. Often dogs may be kept specifically for

aggressive purposes, such for guarding property where illegal activity may be taking

RE

RELEASED UNDER THE OFFICIAL

place, for intimidation, or for the purpose of causing injury to other people or animals.

57. Anecdotal evidence is that animal welfare issues are also extensive.

6 Early experience, socialisation and training, health (physical and psychological).

Page 11 of 27

IN-CONFIDENCE

Options and impact analysis for Problem Area 2

s.9(2)(f)(iv)

ACT

ATI

INFORMATION

T

D UN

AS

RE

RELEASED UNDER THE OFFICIAL

Page 12 of 27

IN-CONFIDENCE

66. Owners of pit bull-type dogs tend to be in the lower socio-economic demographic,

who can less afford extra costs. This is another reason why a long lead-in time is

appropriate. There may be some confusion for owners who did not expect their dog to

be classified by breed or do not agree with the breed classification of their dog.

67. This proposal targets high-risk groups and encourages behaviour changes as opposed

to punitive action and is therefore recommended.

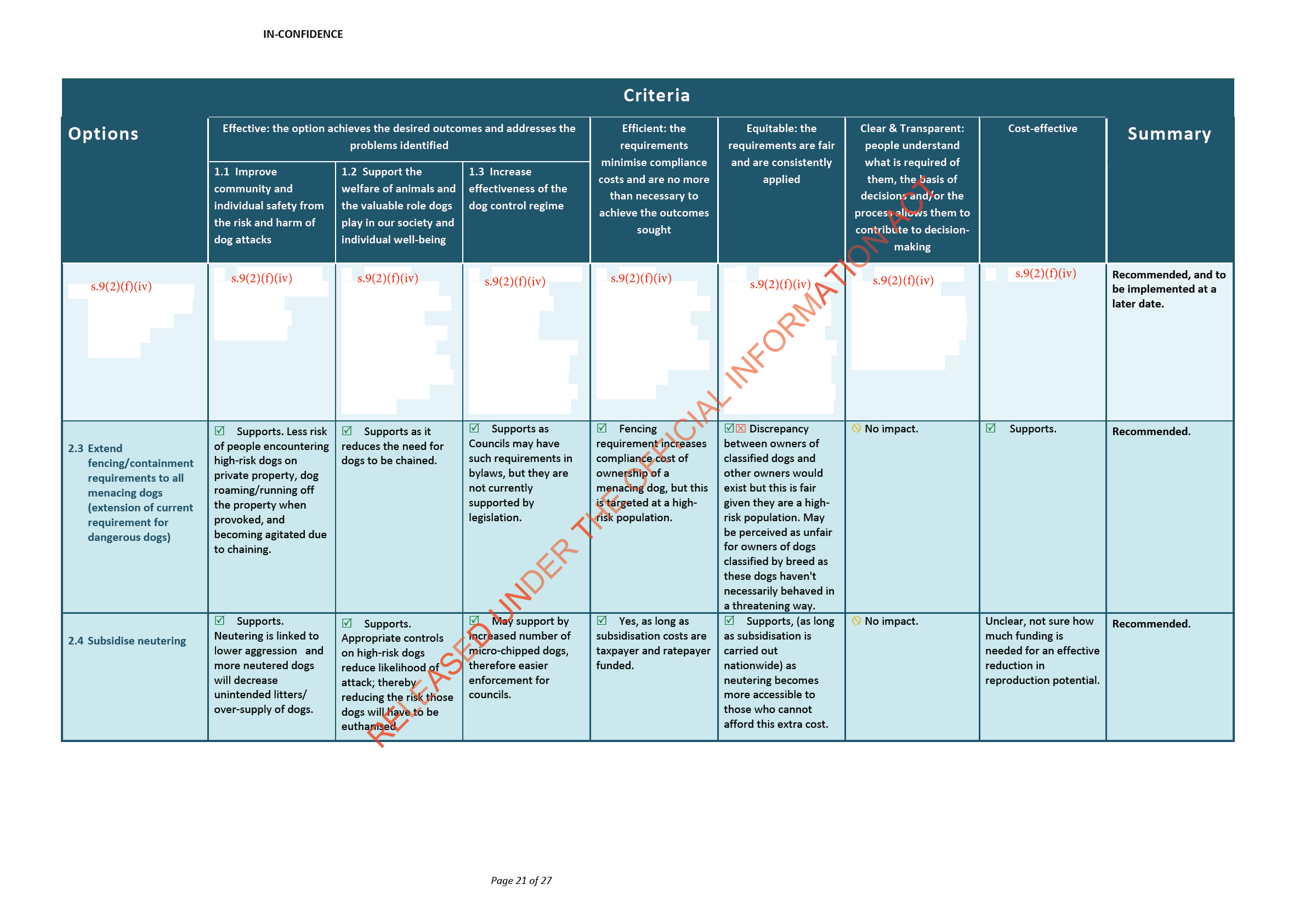

Extend fencing/containment requirements to al menacing dogs

ACT

68. Currently there are containment requirements on owners of dangerous dogs. This

option would extend that requirement to owners of menacing dogs. It would greatly

reduce the risk of people encountering high-risk dogs on private property, dogs

roaming/running off the property when provoked, and becoming agitated due to

chaining. Some councils may have such requirements in bylaws, but they are not

ATI

currently supported by legislation.

69. A fencing requirement increases compliance cost of ownership of a menacing dog, but

this is targeted at a high-risk population. This option is likely to be cost-effective, as a

larger part of dog control work is a result of dogs not being contained on their

property.

INFORMATION

70. This option is recommended.

Subsidise neutering

71. This option would incentivise neutering of dogs. Neutering is linked to lower

aggression and more neutered dogs wi l decrease unintended litters/ over-supply of

dogs. Councils consider this to be one of the most important actions to reduce the

likelihood of dog attacks, as a large number of litters and unintended and unwanted,

This lowers the value of these dogs and if one dog is impounded, often that owner will

T

simply get another dog. This also increases the number of dogs that continue to be

euthanised. As such, subsidised neutering also supports animal welfare considerations.

72. This option is likely to be cost-effective, however it is not possible to confirm this as it

is unclear how many dogs would need to be neutered for an effective reduction in

reproduction potential.

73. This option is recommended.

D UN

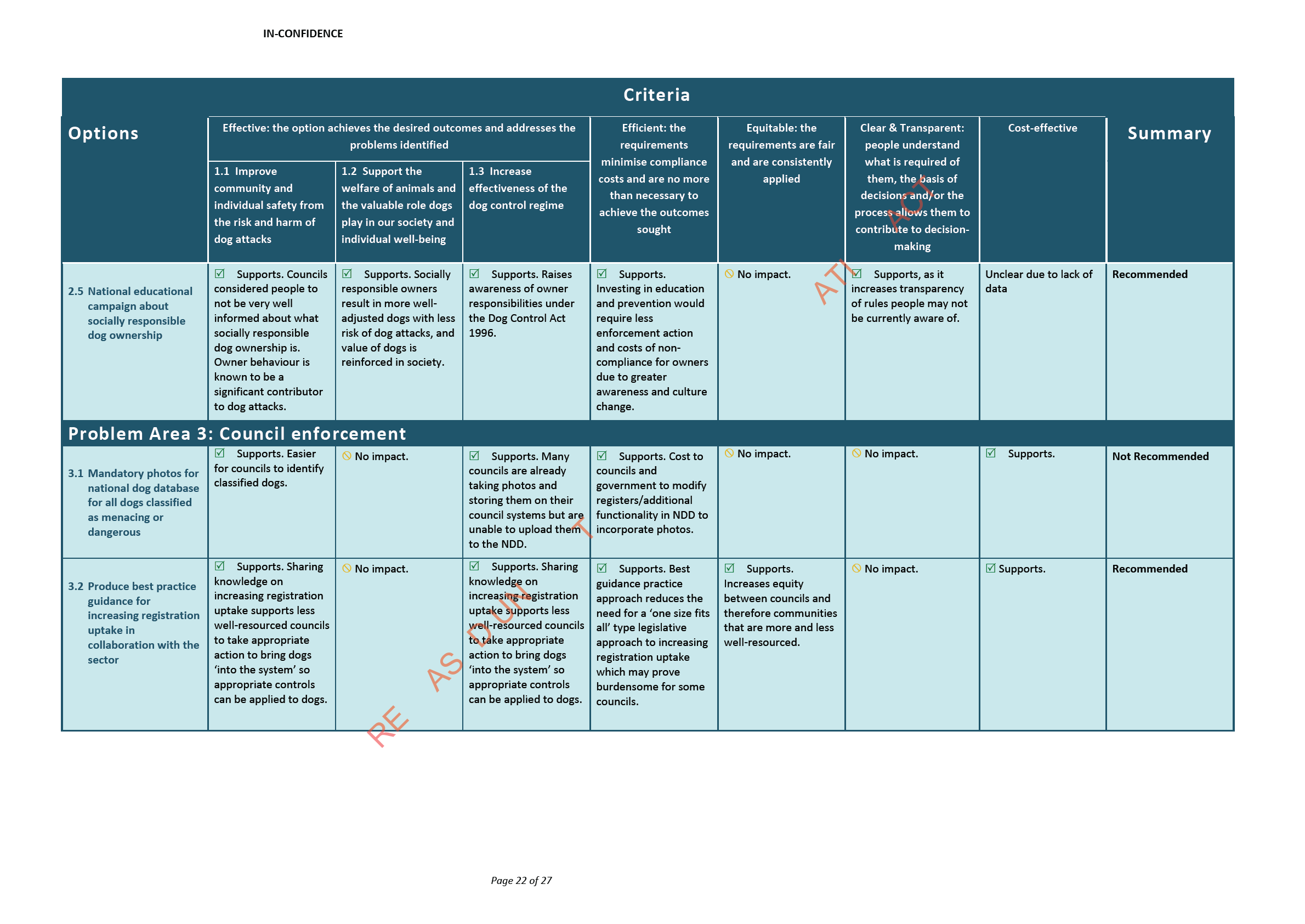

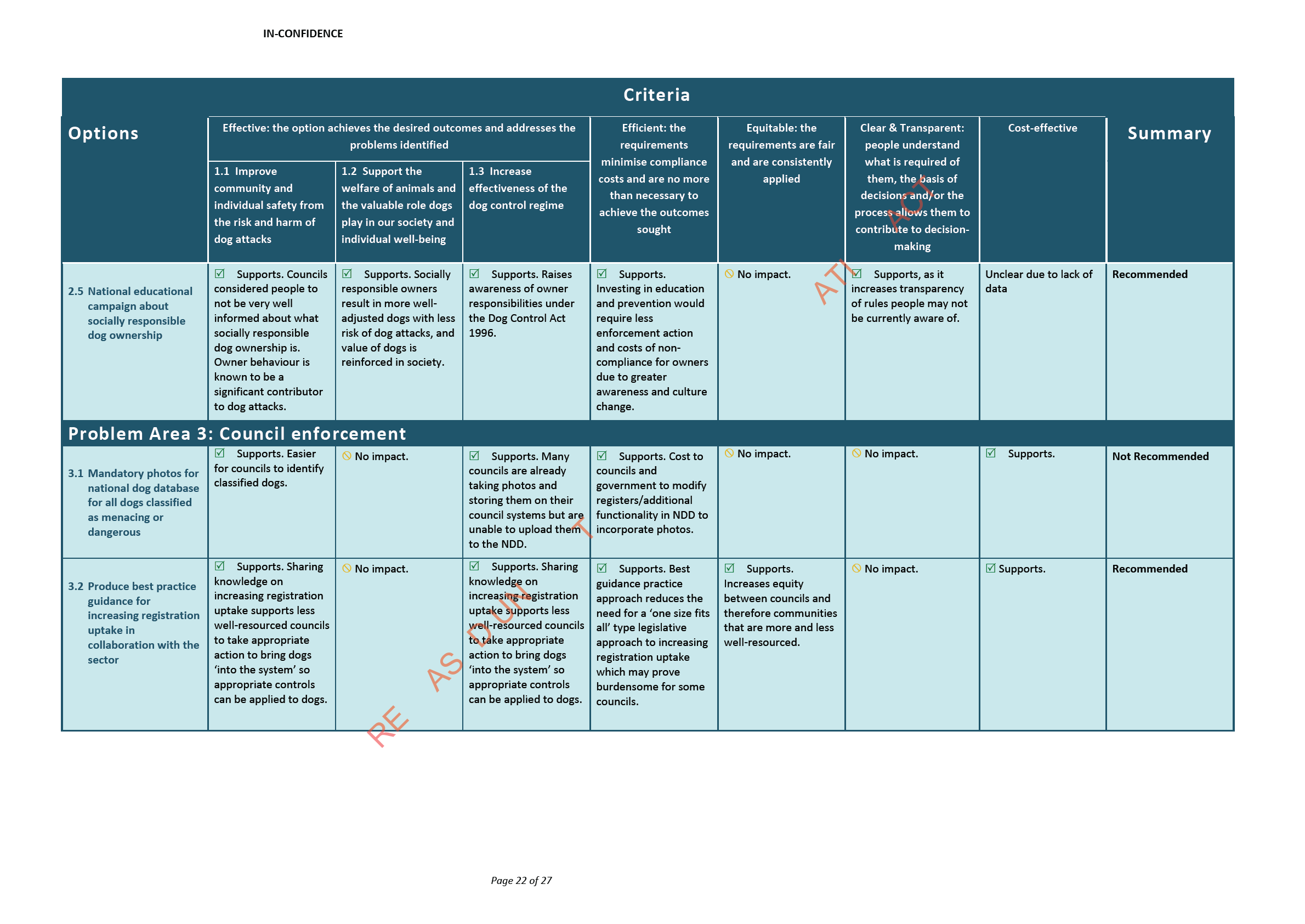

National educational campaign about social y responsible dog ownership

AS

74. Councils considered people to not be very well informed about what socially

responsible dog ownership is. Owner behaviour is known to be a significant

contributor to dog attacks. Socially responsible owners result in more wel -adjusted

RE dogs with less risk of dog attacks, and it reinforces the v

RELEASED UNDER THE OFFICIALalue of dogs in society.

Investment in upfront education and prevention would require less enforcement

action and costs of non-compliance for owners due to greater awareness and culture

change. How much it would cost to carry out an effective public education campaign is

unclear. However, carrying out such a campaign at the national level is considered to

be more cost-effective and individual efforts among councils.

75. This option is recommended.

Page 13 of 27

IN-CONFIDENCE

Problem Area 3: Council enforcement

Status quo

76. Enforcement of the Dog Control Act 1996 is the responsibility of territorial authorities.

Territorial authorities are also responsible for setting dog control policy in their area:

this includes setting registration and other fees and stipulating leash-free exercise

areas and areas where dogs must be kept on a leash or where they are prohibited

(except for disability assist dogs).

ACT

77. Dog control officers can seize dogs that are not under direct control of a person and

are free to leave the property along with dogs that are straying, unregistered, behaving

aggressively, or not receiving adequate food, water or shelter.

78. Every council must keep a record of all dogs registered. All councils are required to

ATI

provide information on the dog and its owner along with its microchip number (if it has

one) to the national dog database.

79. There are also mandatory annual reporting requirements on councils under s10A of

Dog Control Act 1996.

INFORMATION

There are potential y a large number of unregistered and un-microchipped dogs in New

Zealand; unregistered dogs are over-represented in impounds and attacks

80. Risk associated with dogs is greatly increased by not having appropriate controls on

dogs. Applying the appropriate controls to dogs requires dogs being ‘in the system’

rather than ‘underground’.

7 Dog registration is considered to be the cornerstone of

effective dog control because it links dog control services to dog owners, allows for the

appropriate placement of controls on individual dogs, and provides a source of

revenue for dog control activities. Micro-chipping for identification is an important

part of connecting a particular dog to an incident and prior incidents that may have

T

occurred.

81. The recent Auckland Council amnesty which resulted in over 1500 unregistered dogs

brought forward for registration indicates that the current dog registration system is

not effectively enforced. There are 100,000 registered dogs in Auckland and Auckland

Council estimates that there are approximately another 100,000 unregistered dogs.

There are indications there is a similar problem of under-registration across the

D UN

country, although evidence is limited.

Councils are not receiving accurate information about dog attacks in their districts

AS

82

Councils can only investigate attacks they are made aware of, generally by the victim

or someone else involved in the incident. There are no mandatory requirements on

health professionals or agencies (such as the Accident Compensation Corporation) to

RE

RELEASED UNDER THE OFFICIAL

notify councils of an incident they become aware of. Councils have noted that without

accurate information about the presence and behaviour of dogs in their district, it is

not possible for councils to effectively address high-risk dogs or owners.

7 It is for this reason that any sort of ban on ownership of dog types or breeds is not considered a feasible

option and therefore is not assessed alongside other options in this analysis.

Page 14 of 27

IN-CONFIDENCE

Councils are not going through the full prosecution process due to the expense of this

process and limited resources to work with

83. There are members of society for whom infringements are not an effective deterrent.

However, prosecutions may not be able to be taken as much as territorial authorities

would like, as they do not have the budget.

Options and impact analysis for Problem Area 3

ACT

Mandatory photos for national dog database for all dogs classified as menacing or

dangerous

84. This option would make it easier for councils to identify classified dogs moving across

council boundaries. It would also promote the taking of photos (important of

ATI

evidentiary purposes) of classified dogs where currently this may not be council

practice. Currently many councils are taking photos, which they store on their council

systems but they are unable to upload them to the NDD. Making it mandatory would

result in national consistency which is necessary otherwise the approach would be of

limited value.

INFORMATION

85. There would be cost to councils and government to modify registers for the additional

functionality in the national dog database to incorporate photos. However, because

the NDD has already been established, this measure is considered to be cost-effective.

This option is not recommended.

Produce best practice guidance for increasing registration uptake in collaboration with the

sector

86. This option would mean the production of best practice guidance, in col aboration with

the sector. Sharing knowledge on increasing registration uptake supports less well-

T

resourced councils to take appropriate action to bring dogs ‘into the system’ so

appropriate controls can be applied to dogs.

87. A best practice guidance approach reduces the need for a ‘one size fits al ’ type

legislative approach to increasing registration uptake which may prove burdensome

for some councils and decreases room for innovation. This option is recommended.

D UN

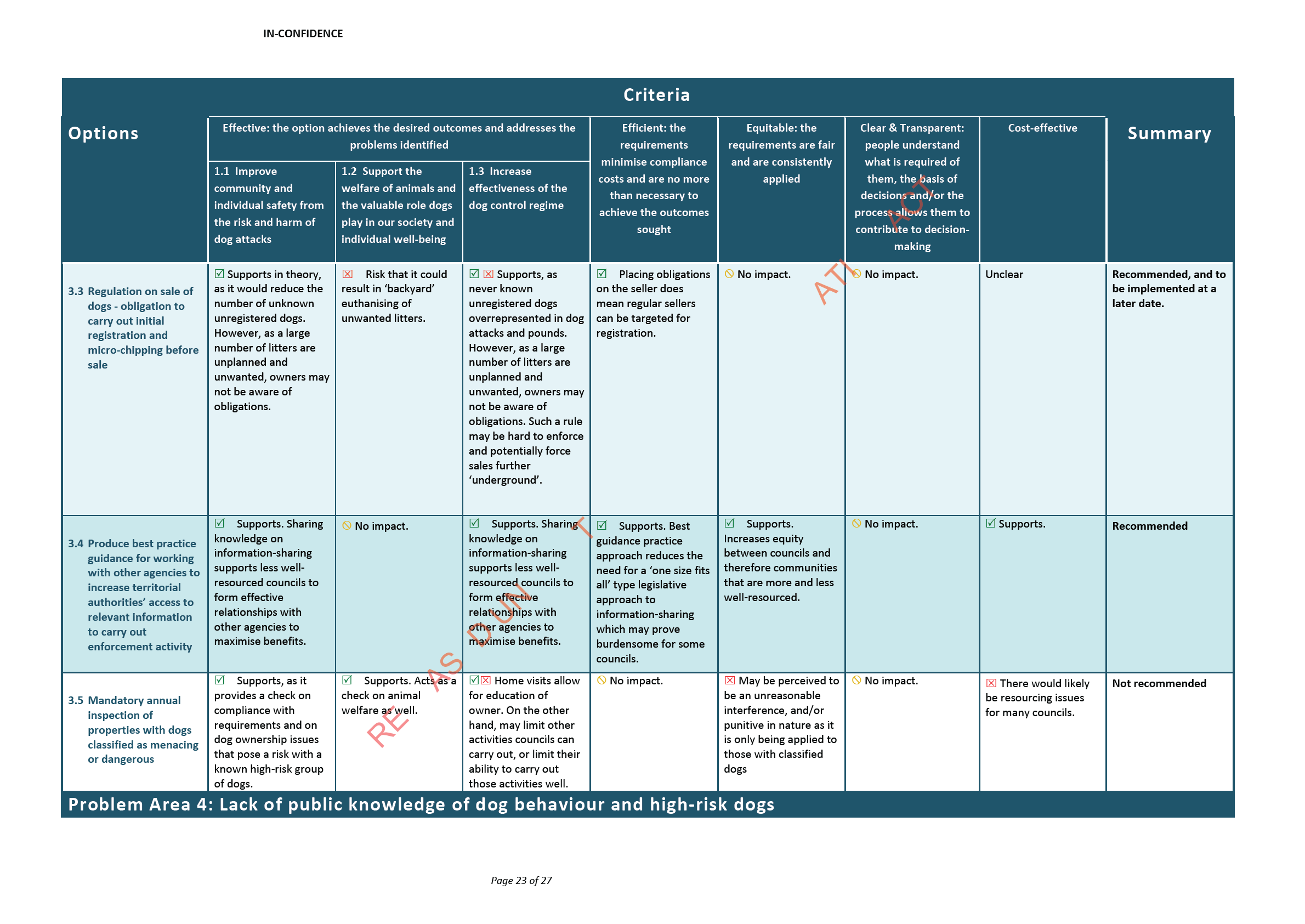

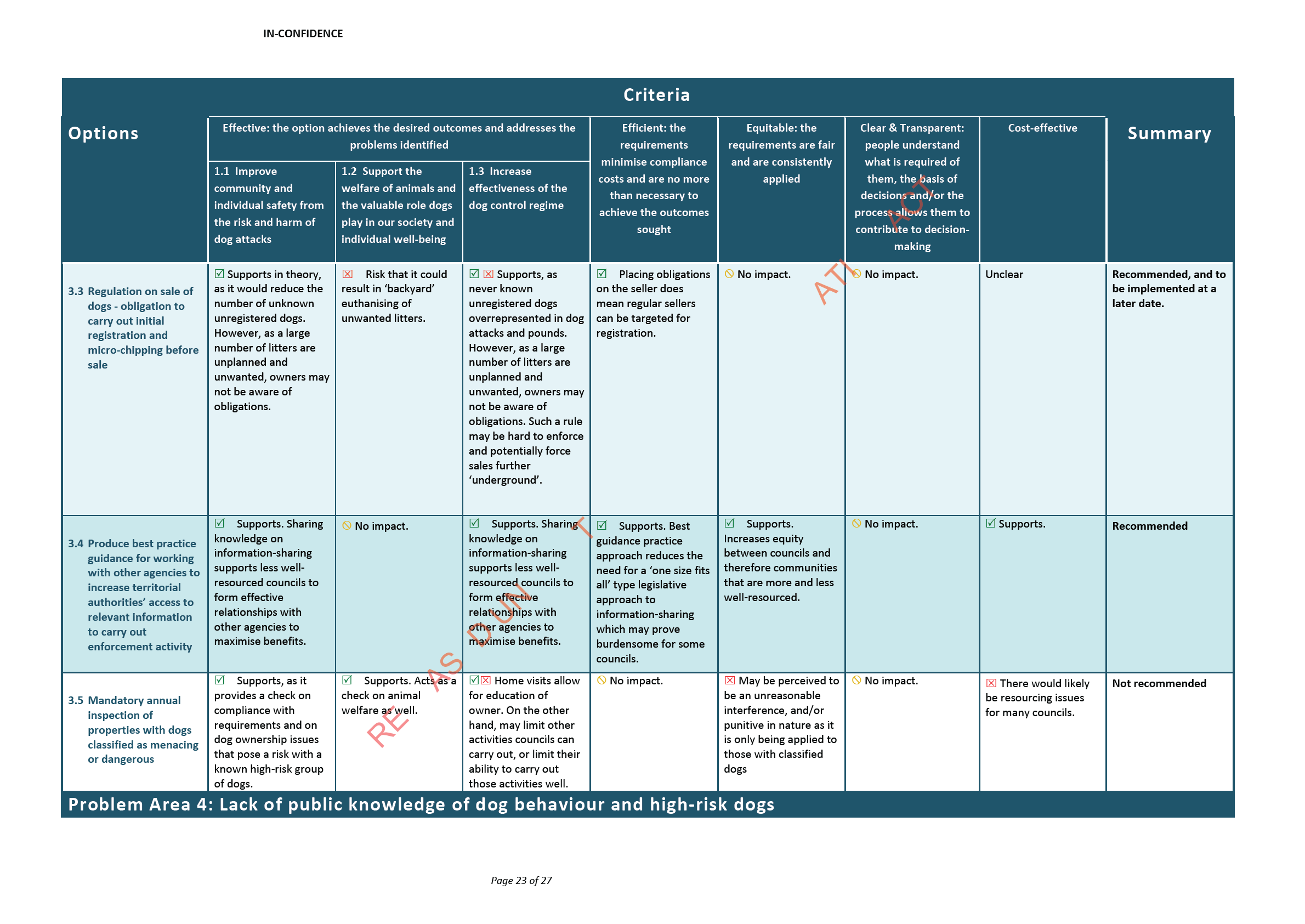

Regulation on sale of dogs - obligation to carry out initial registration and micro-chipping

before sale

AS

88

Never known unregistered dogs overrepresented in dog attacks and pounds. Currently

there are obligations on an owner to register and microchip their dog. This option

would also place obligations on a seller to ensuring registration and micro-chipping

RE have been carried out. This option aims reduce the numbe

RELEASED UNDER THE OFFICIAL r of unknown unregistered

dogs. However, as a large number of litters are unplanned and unwanted, owners may

not be aware of obligations. A large number of ‘sales’ are informal. There is a risk that

such a policy could result in ‘backyard’ euthanising of unwanted litters. Therefore such

a rule may be hard to enforce and potentially force sales further ‘underground’. This

option is recommended for implementation at a later date.

Page 15 of 27

IN-CONFIDENCE

Produce best practice guidance for working with other agencies to increase territorial

authorities’ access to relevant information to carry out enforcement activity

89. This option would mean the production of best practice guidance, in col aboration with

the sector. Some councils have excellent working relationships with other agencies

such as the Police, and Child, Youth and Family. This is because there are shared

interests and an understanding that there are efficiencies in working together. This is

an area of practice, rather than policy and therefore insights into how to work with

other interested agencies may not be actively shared across the local government

sector. Sharing knowledge on information-sharing supports less wel -resourced

ACT

councils to form effective relationships with other agencies to maximise benefits

90. A best practice guidance approach reduces the need for a ‘one size fits al ’ type

legislative approach to information-sharing which may prove burdensome for many

councils. Such a measure is also likely to be cost-effective.

ATI

91. This option is recommended.

INFORMATION

s.9(2)(f)(iv)

94. This option is not recommended.

T

Problem Area 4: Lack of public knowledge of dog behaviour

and high-risk dogs

95. The remaining factor determinant of whether a dog will attack is victim behaviour.

96. Because of the inherent risk associated with dogs, there will always be potential

D UN

victims who are vulnerable to attack. Risks can be mitigated by having enhancing the

ability of the public to be safer around dogs. People often do not know when they may

be ent

ASering a high-risk situation, how to recognise and deal with an imminent attack or

what to do when one has begun. At an even more basic level, only a smal proportion

of people know how to interact with dogs and understand dog behaviour.

RE

RELEASED UNDER THE OFFICIAL

Status quo

97. Anecdotal evidence from council officers suggests that victim behaviour is a significant

contributor to outcome. Children are often running away, and children and adults alike

may often be taunting an already somewhat agitated dog. Children and often

unsupervised by an adult when they are attacked.

Page 16 of 27

IN-CONFIDENCE

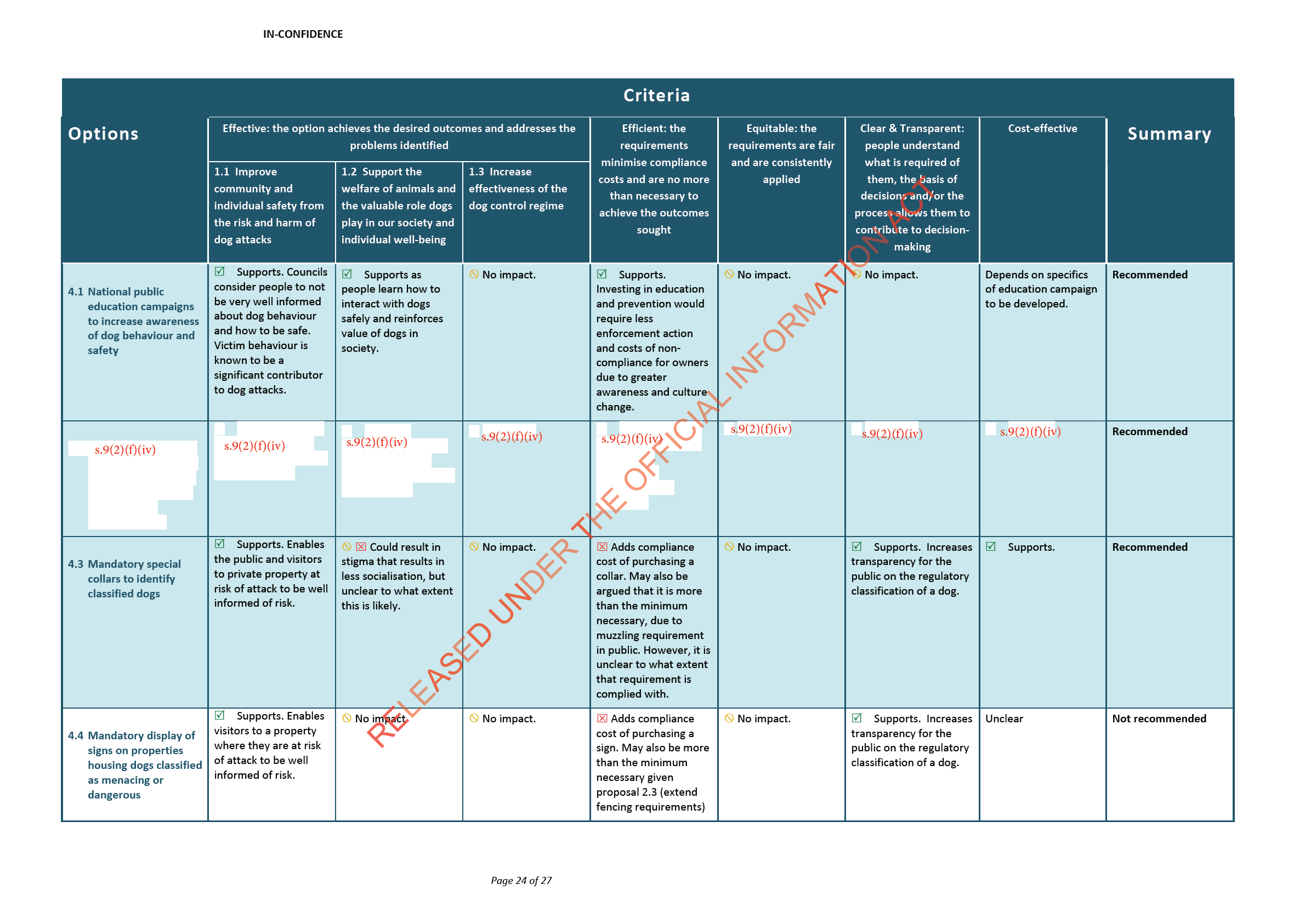

Options and impact analysis for Problem Area 4

National public education campaigns to increase awareness of dog behaviour and safety

98. The general public is not very wel informed about dog behaviour and how to be safe.

Victim behaviour is known to be a significant contributor to dog attacks according to

international findings. Investing in education and prevention would require less

enforcement action and costs of non-compliance for owners due to greater awareness

and culture change.

ACT

99. How much it would cost to carry out an effective public education campaign is unclear.

However, carrying out such a campaign at the national level is considered to be more

cost-effective and individual efforts among councils. This option is recommended.

ATI

s.9(2)(f)(iv)

This option is

INFORMATION

recommended.

Mandatory special collars to identify classified dogs

101. Supports. Enables the public and visitors to private property at risk of attack to be wel

informed of risk, as well as those out in public where the dog is not wearing a muzzle.

The requirement to where a signifying collar could potential y result in stigma that

results in less socialisation for the dog, but unclear to what extent this is likely. Also,

currently menacing and dangerous dogs are required to wear a muzzle when in public.

Therefore it could be argued this requirement is more than the minimum necessary, as

T

a muzzle is also a visual sign. However, it is not clear to what extent the muzzling

requirement is complied with. A large number of infringements are issued each year

for failure to muzzle.

102. This option adds compliance cost of purchasing a collar, however is considered to be

cost-effective. This option is recommended.

D UN

Mandatory display of signs on properties housing dogs classified as menacing or

dangerous

AS

103. This option enables visitors to a property where they are at risk of attack to be well

informed of risk. As most attacks occur in the home, this option is considered to be the

right area for action to reduce risk of dog attacks. The option adds compliance cost for

RE owners of purchasing a sign. It may also be more than the

RELEASED UNDER THE OFFICIAL minimum necessary given

proposal 2.3 (extend fencing requirements). As such, this option is not recommended.

Page 17 of 27

ACT

INFORMATION

RELEASED UNDER THE OFFICIAL

ACT

INFORMATION

RELEASED UNDER THE OFFICIAL

ACT

INFORMATION

RELEASED UNDER THE OFFICIAL

ACT

INFORMATION

RELEASED UNDER THE OFFICIAL

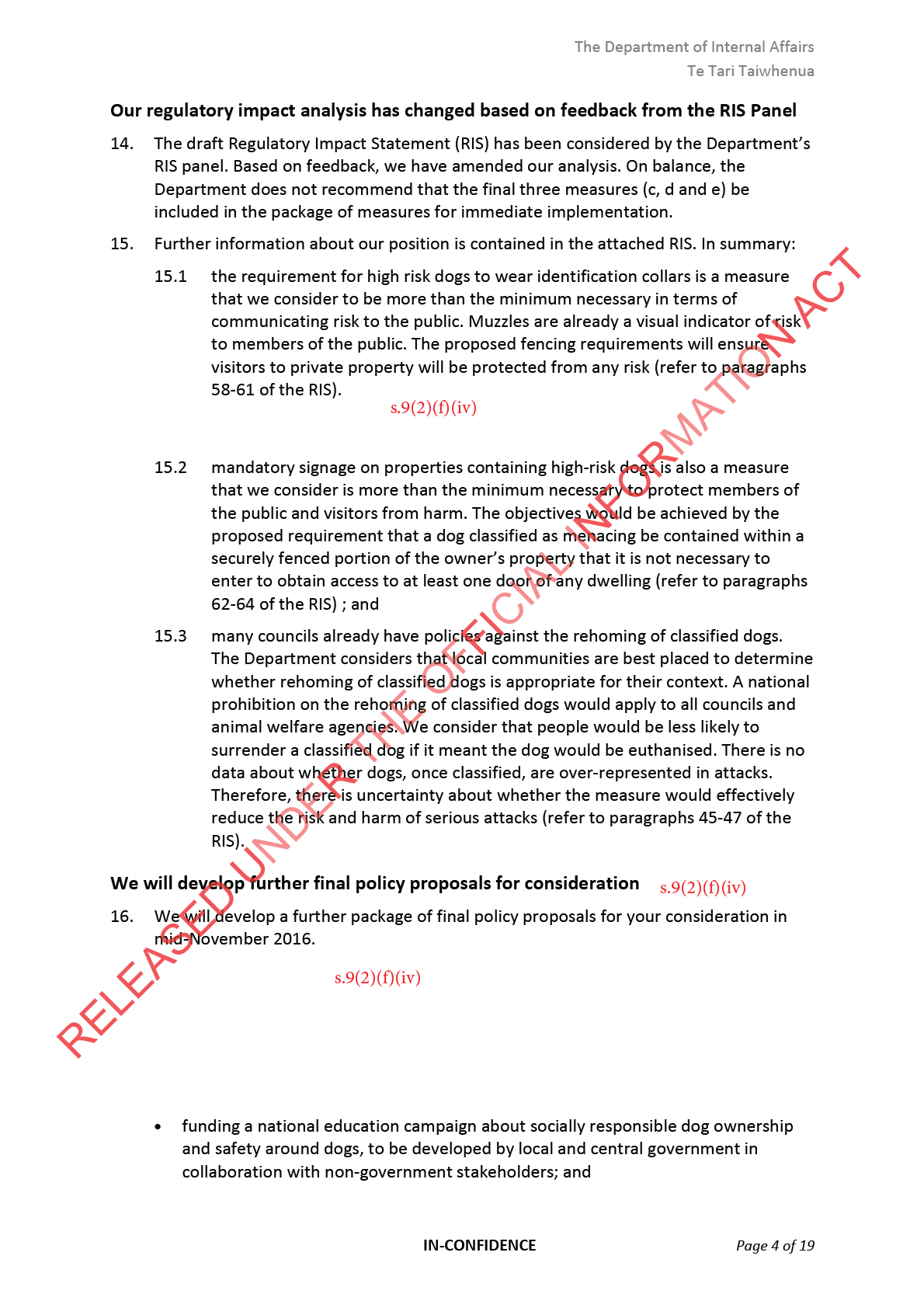

Consultation

4 In the preparation of these proposals, a range of external stakeholders were also

consulted, including Local Government New Zealand, the Society of Local Government

Managers, Auckland Council, the New Zealand Institute of Animal Management

(previously known as the New Zealand Institute of Animal Control Officers), the New

Zealand Association of Plastic Surgeons, the New Zealand Kennel Club, Federated

Farmers of New Zealand, Rural Women New Zealand, the Veterinary Council of New

ACT

Zealand, Dog behaviour experts, Trade Me, and the Royal New Zealand Society for the

Protection of Animals the Pit bul Club, and the American Staffordshire Terrier Club.

5 We also undertook targeted engagement with victims of dog bites and dog owners in

Auckland and Wel ington. Officials also met with, farmers and other members of the

ATI

rural community, and animal control officers. An online engagement survey was used to

capture the sentiment of the general public about areas for improvement to the dog

control regime. The two week survey period resulted in over 3000 responses.

6 This engagement enabled officials to gain some understanding of the nature and the size

of dog control problems and to identify potential solutions. INFORMATION

Conclusions and recommendations

7 The Department recommends the following package of options:

Measures that transition New Zealand towards a lower risk dog population:

• Mandatory neutering of all dogs classified as menacing (remove territorial

authority discretion)T

• Differential registration fees: Require territorial authorities to provide a

registration fee reduction for dogs that have passed temperament and

sociability testing

• Introduce a sub-classification under menacing, for dogs kept for an aggressive

purpose (hunting dogs)

D UN

Measures that encourage responsible dog ownership behaviour and discourage

negligent and reckless behaviour:

•

AS s.9(2)(f)(iv)

• Extend fencing/containment requirements to al menacing dogs (extension for

RE

requirement for dangerous dogs)

RELEASED UNDER THE OFFICIAL

• Subsidise neutering

• National educational campaign about socially responsible dog ownership

Measures that enhance the ability of territorial authorities to take effective

preventative and enforcement action against high-risk owners and high-risk dogs:

• s.9(2)(f)(iv)

Page 25 of 27

• Produce best practice guidance for increasing registration uptake in

collaboration with the sector

• Produce best practice guidance for working with other agencies to increase

territorial authorities’ access to relevant information to carry out enforcement

activity

Measures that help to protect individuals from becoming victims of dog attacks:

• National public education campaigns to increase awareness of dog behaviour

and safety

ACT

•

s.9(2)(f)(iv)

• Mandatory special collars to identify classified dogs

ATI

8 These options are considered to be able to reduce the risk and harm of dog attacks.

Implementation plan

INFORMATION

9 These proposals wil be implemented as part of three phases of work.

•

Legislative phase: a one to two year process to amend the Act and develop

regulations to address deficiencies in the current dog control legislation;

•

Best practice phase: a one to two year process (concurrent to the legislative

phase), led by the local government sector, to develop best practice guidance for

the local government sector about mplementation of the Act, amendments, and

associated regulations; and

•

Public education phase: a five to ten year process, led by central and local

government, to influence societal change in attitudes about responsible dog

T

ownership and safety around dogs

10 Phases 2 and 3 wil be carried out in col aboration with local government and other

stakeholders.

Monitoring

D UN

, evaluation, and review