Methamphetamine: History,

Pathophysiology, Adverse Health

Effects, Current Trends, and Hazards

Associated with the Clandestine

Manufacture of Methamphetamine

David Vearrier, MD,

Michael I. Greenberg, MD, MPH,

Susan Ney Miller, MD, Jolene T. Okaneku, MD, and

David A. Haggerty, MD

Introduction

Developed as an amphetamine derivative, methamphetamine quickly

became a popular medication during the 1940s and 1950s, prescribed for

a variety of indications. Extensive diversion of methamphetamine during

the 1960s and an increasing awareness of the adverse health effects

associated with methamphetamine led to the withdrawal of most of the

indications for licit methamphetamine use and declines in legal produc-

tion of the drug. However, the illicit manufacture of methamphetamine

increased to meet the demand for methamphetamine, and methamphet-

amine abuse has increased with variable geographic penetrance over the

last 30 years.

Methamphetamine is an indirect sympathomimetic agent that is distin-

guished from amphetamine by a more rapid distribution into the central

nervous system (CNS), resulting in the rapid onset of euphoria that is the

desired effect for those abusing the drug. Increases in monoamine

neurotransmission are responsible for the desired effects—wakefulness,

energy, sense of well-being, and euphoria—as well as the excess

sympathetic tone that mediates many its adverse health effects.

Methamphetamine is associated with adverse effects to every organ

system. Although the most significant morbidity and mortality occur

because of cardiovascular effects, such as myocardial infarction and

hypertensive crisis, no organ system remains unscathed by methamphet-

Dis Mon 2012;58:38-89

0011-5029/2012 $36.00 ⫹ 0

doi:10.1016/j.disamonth.2011.09.004

38

DM, February 2012

link to page 38

amine abuse. Methamphetamine abuse is a serious public health problem

because of both costs associated with treatment of methamphetamine-

associated adverse health effects and crime and violence perpetrated to

obtain methamphetamine or because of methamphetamine-related aggres-

sive behavior.

Of further concern are the hazards and environmental effects of “meth

labs,” frequently small operations housed in residential buildings, where

methamphetamine is manufactured from precursor chemicals. Hazards

associated with methamphetamine laboratories include blast injuries,

thermal burns, chemical injury, and toxic exposures. Unfortunately, a

significant percentage of methamphetamine laboratories are housed in

residential buildings where children are present, potentially resulting in

pediatric exposures to methamphetamine, precursor chemicals, and drug

use paraphernalia.

This article reviews the history of methamphetamine use and abuse,

describes its mechanism of action and pathophysiology, delineates

adverse health effects, and describes current epidemiologic trends. It also

discusses the process and precursor chemicals involved in the manufac-

ture of methamphetamine and hazards associated with clandestine meth-

amphetamine laboratories.

The History of Methamphetamine

Discovery and Early Methamphetamine Use

Amphetamine-type stimulants, which include methamphetamine and

amphetamine, were developed as synthetic alternatives to ephedra.

Ephedra is a botanic extract of

Ephedra sinica and has been used in

traditional Chinese medicine as ma huang for over 5000 years. In 1885,

ephedrine, the active alkaloid present in ephedra, was extracted and

studied. Ephedrine was recognized to be similar to epinephrine, which

was also isolated around the turn of the 20th century, but could be taken

orally, had a longer duration of action, produced more pronounced and

dependable CNS stimulation, and had a larger therapeutic index. The

search for a synthetic ephedrine substitute resulted in the development of

amphetamine-type stimulants, produced via modification of the ephedrine

skeleton with the pharmaceutical goals of CNS stimulation, bronchodi-

lation, or nasal

vasoconstriction.1-3 Japanese chemist Akira Ogata first

synthesized methamphetamine in 1919 using ephedrine as a precursor.

Early amphetamine use was primarily via nasal insufflation. In 1932,

Smith, Kline, and French began marketing the amphetamine inhaler

Benzedrine for use in asthma and congestion. The insufflated amphet-

DM, February 2012

39

link to page 38 link to page 38 link to page 38 link to page 38 link to page 38 link to page 38

amine caused vasoconstriction of the nasal mucosa, decreasing mucosal

swelling and edema, and the inhaler was initially available without a

prescription. In 1959 the S. Pfeiffer Company began producing Valo

inhalers that contained 150-200 mg of

methamphetamine.4,5

The Heyday of Licit Methamphetamine Use

Desirable “side effects” associated with amphetamine-type stimulant

inhalers were noted, resulting in expanding indications for amphetamines

and the introduction of oral amphetamine-type stimulant medications. For

example, the side effect of wakefulness suggested its value in treating

narcolepsy and conditions of drowsiness or exhaustion. Its appetite-

depressant effects led to the use of amphetamines, including metham-

phetamine, for weight

loss.4 Other early indications and off-label uses for

methamphetamine included schizophrenia, asthma, morphine addiction,

barbiturate intoxication and narcosis, alcoholism, excessive anesthesia

administration, migraine, heart block, myasthenia gravis, myotonia,

enuresis, dysmenorrhea, Meniere’s disease, colic, head injuries, hypoten-

sion, seasickness, persistent hiccups, heart block, head injuries, infantile

cerebral palsy, codeine addiction, tobacco smoking, pediatric behavior

issues, Parkinson’s disease, and

epilepsy.5 Amphetamines and their

analogs were being presumptively promoted as effective and safe without

risk of addiction. In 1940, methamphetamine tablets under the commer-

cial name Methedrine were introduced to the market by the Burroughs

Wellcome

Company.1,6

Methamphetamine was also used by the military. In World War II,

methamphetamine was available to military personnel as Pervitin in

Germany and Philopon in Japan. Temmler Pharmaceutical Company

introduced Pervitin in 1938 to the European market. Pervitin was

available as 3 mg tablets that physicians could provide for the German

military units. Dainippon Pharmaceutical Company made Philopon avail-

able in Japan in 1941. Methamphetamine in Germany and Japan and

amphetamine use in the USA were used to increase alertness, reduce

fatigue, and suppress the appetite of

soldiers.4,5 Use of methamphetamine

extended to include war-related industry workers to improve shift work

abilities. Later, the USA military used amphetamines in the Korean War

and the Vietnam War. Today, the use of stimulants, like amphetamines

and methamphetamine, is permitted to treat combat fatigue and promote

wakefulness in combat. A survey of Persian Gulf War pilots reported

substantial use of stimulants to decrease fatigue during

combat.1

During the 1940s and 1950s, methamphetamine was liberally prescribed

for numerous indications and large quantities of it were licitly produced.

40

DM, February 2012

link to page 38 link to page 38 link to page 38 link to page 38 link to page 38

A broad segment of the population used methamphetamine for a variety

of reasons. Housewives, truck drivers, students, and professionals used

amphetamines and methamphetamine to promote wakefulness, improve

mood or attention, and lose weight. Numerous users gradually increased

the doses they used as they developed tolerance to the effects of the

drugs.1,4,5

The ways in which the medications could be misused spread quickly.

Inhalers could be broken open and the contents ingested directly or filters

could be soaked in alcohol or coffee to reduce irritation of the mouth.

Extracting drugs from inhalers for intravenous injection was another

method of abuse, first being reported in 1959. Reports of robberies,

murder, and other violent acts were linked to inhaler

misuse.4,5 Prison

populations also abused these inhalers, which could be smuggled within

containers or letters. Methamphetamine abusers would combine the drug

with illicit substances, such as heroin or barbiturates. Use in conjunction

with a barbiturate produced what was referred to as “bolt and jolt,” a

street term for the increased pleasure associated with this combination of

drugs.1,4,5

In response to a Food and Drug Administration warning of misappli-

cation of the inhalers, some pharmaceutical companies responded by

adding a denaturant to deter ingestion. Abusers adapted by injecting the

product after boiling off the denaturant. In 1959, the Food and Drug

Administration restricted amphetamine and dextroamphetamine inhalers

to prescription-only distribution. Methamphetamine inhalers, such as

Valo, continued to be marketed until 1965. Starting with Benzedrine in

1949, most of these nasal inhalers were removed from the market by

1971.4

The Gradual Recognition of Adverse Health Effects

Reports of serious adverse health effects of amphetamines began

appearing as early as 1935. One early study reported that even at the

recommended therapeutic dose of an amphetamine inhaler, most subjects

experienced pallor, flushing, palpitations, and increases in pulse rate and

blood pressure. Six of the 20 subjects in that study developed multiple

extrasystoles and chest pain. Other studies reported convulsions, coma,

loss of consciousness, nausea, vomiting, difficulty breathing, tremor,

tetany, tachycardia, pallor, psychosis, and

cyanosis.4,5

As an early response to recognition of potential dangers associated with

amphetamine use and misuse, state and federal restrictions were enacted,

halting the over-the-counter sale of oral amphetamine preparations. These

restrictions required that amphetamines be marketed under a label

DM, February 2012

41

link to page 38 link to page 5 link to page 38

TABLE 1. Street names for methamphetamine

Meth

Dimethylphenethylamine

Speed

Methedrine

Crystal meth

Desoxyn

Ice

Chalk

Batu

Poor man’s cocaine

Shabu

Tweak

Glass

Uppers

Tina

Biker’s coffee

Crank

Trash

Go-fast

Black beauties

Stove top

Methlies quick

Yaba

Yellow barn

warning against use except under medical supervision. However, inhalers

containing amphetamines or methamphetamine were not covered under

this

regulation.4

As the abuse of methamphetamine increased, so did the number of

monikers associated with the drug

(Table 1). During the 1960s, the term

“speed freaks” became popular to describe high-dose, compulsive users

of amphetamine and methamphetamine.

1,5 Demographically, amphet-

amine-type stimulant abuse at that time was most common among

Caucasians with a middle-class socioeconomic status. The prevention

slogan “speed kills” was introduced by antidrug activists during the

1960s, prompted by the serious medical and psychiatric consequences of

abuse, although some argue that the slogan may have done as much to

popularize the abuse of amphetamines as to prevent it.

In response to the burgeoning diversion of legally produced amphet-

amine-type stimulants to the criminal underworld, the USA federal

government passed the Drug Abuse Control Amendments of 1965, which

required record keeping throughout the manufacture, distribution, pre-

scription, and sale of these medications. Ultimately, this bill was

ineffective in preventing diversion of amphetamine-type stimulants to the

black market. Subsequently, the Comprehensive Drug Abuse Prevention

and Control Act of 1970 limited the accepted medical uses for prescribed

amphetamines and classified amphetamines as Schedule II medications.

Over the course of the 1970s, there was a gradual decrease in the number

of amphetamines prescribed and decreasing legal production of the drugs

was resulting in less diversion to the street. A 90% decrease from

prelegislation level was accomplished by the mid-1980s; the rate at which

amphetamines was being prescribed had decreased by 90% from the

42

DM, February 2012

link to page 38 link to page 38 link to page 38 link to page 38 link to page 38 link to page 38 link to page 38

heyday of the 1960s and continued to decrease by another one-third by

1990.1

Diversion of Pharmaceutical Products and Illicit

Manufacture

It has been estimated that legal pharmaceutical production of amphet-

amine was 3.5 billion tablets in 1958, enough to supply every person in

the USA at the time with 20 standard

doses.4 Prescriptions peaked in 1967

at 31 million, whereas amphetamine production increased to 10 billion

tablets by

1970.7 A consequence of the overproduction of amphetamines

was diversion to illegal traffic. Supplies of amphetamine and metham-

phetamine from legal production found their way to the black market via

pharmaceutical companies, wholesalers, pharmacists, and

physicians.4,6

Illegal manufacture of methamphetamine emerged as a new source of

the drug and became increasingly important as a diversion of licitly

produced methamphetamine became more difficult. The first known illicit

production of methamphetamine occurred in 1962 in San Francisco, CA.

During the late 1960s, the Haight-Ashbury neighborhood of San Fran-

cisco became a center of methamphetamine abuse, particularly among

young adults and college students. Illegal manufacture was imperfect and

the methamphetamine contained substantial amounts of impurities. How-

ever, by the mid-1980s, virtually all street methamphetamine was

manufactured in clandestine laboratories rather than diverted from legally

produced pharmaceutical

products.5,7,8

Association with motorcycle gangs led to the early reputation of

methamphetamine as a “biker drug” in the 1960s and 1970s. The

nickname “crank” originated from the bikers’ tendency to transport the

methamphetamine in the crankcases of their motorcycles. Motorcycle

gangs, including Hell’s Angels, were responsible for manufacturing and

distributing methamphetamine along the Pacific Coast and have been

associated with distribution networks that contributed to a rise in

methamphetamine use in the 1960s. These motorcycle gangs contributed

up to 90% of methamphetamine produced in the USA in the 1970s and

1980s. Their customer base was primarily in Southern California and

Oregon and much of the distribution involved the intravenous or

crushable tablet

form.1 Eventually, as illicit production of methamphet-

amine shifted to Mexico, the motorcycle gangs transitioned to purchasing

methamphetamine from Mexican manufacturers and focused their profit-

making on the distribution of the

drug.1,7

Following a lull in amphetamine and methamphetamine use during the

1970s and early 1980s because of declining prescriptions and licit

DM, February 2012

43

link to page 38 link to page 38 link to page 7 link to page 38

TABLE 2. Selected methods of self-administration of methamphetamine

Method of

Slang Terms Associated

Administration

with Technique

Anal suppository

Butt rocket, plugging

Ingestion

None

Inhalation

Chasing the white dragon

Insufflation

Snorting

Intravenous injection

Banging, mainlining, slamming

Vaginal suppository

None

production, methamphetamine use in the West Coast began to increase

again in the mid-1980s and steadily spread into the Midwest through the

1990s. The Northeast and Mid Atlantic were relatively spared up until just

this past

decade.1 Epidemiologically, methamphetamine abuse in the

1980s occurred predominantly among Caucasian males, many of whom

were truck drivers, construction workers, and other blue-collar workers.

During this period, a new form of methamphetamine, methamphet-

amine hydrochloride, was popularized. “Ice” or “crystal meth,” as

methamphetamine hydrochloride was called, could be smoked, resulting

in an almost immediate onset of euphoria and contributing to its

increasing popularity among amphetamine abusers. The epidemic started

in West Honolulu and included those from the working class, public

housing projects, and Filipino community, but over time expanded to

Hawaii and the West Coast and then throughout the

USA.7,8 Table 2

describes some of the more popular methods of methamphetamine

self-administration. More legislation was passed during this period, which

included the Federal Controlled Substance Analogue Enforcement Act of

1986 and Chemical Diversion and Trafficking Act of 1988, with the latter

act regulating precursor chemicals in an attempt to stem the illicit

production of

methamphetamine.2

The 1990s experienced an expansion of local manufacture and regional

distribution of methamphetamine. Manufacturing in both “mom-and-pop

labs” and large-scale “super labs” became widespread throughout the West

Coast and Midwest states. In areas with adequate illicit drug infrastructure

and high methamphetamine demand, like the Central Valley of California,

organized networks of producers and distributers predominate. In areas with

less established infrastructure, the methamphetamine supply is produced by

local “cooks” and distributed by a relational network of people. Clandestine

laboratories are often, although not exclusively, set up in rural areas because

of the strong odors associated with methamphetamine production and are

moved frequently to prevent detection.

44

DM, February 2012

link to page 38 link to page 38 link to page 38 link to page 9 link to page 38 link to page 38 link to page 38

In response to an epidemic of methamphetamine abuse, the federal

government has passed measures designed to stem rising methamphet-

amine manufacture and abuse. The Methamphetamine Control Act of

1996 was passed to strengthen penalties and tighten controls on precur-

sors.7,8 The most recent federal law is the Combat Methamphetamine

Epidemic Act of 2005, which regulates the purchase of products contain-

ing pseudoephedrine, ephedrine, and phenylpropanolamine, all of which

can be used in the manufacture of methamphetamine. Specifically, drugs

containing these precursors must be stored behind a pharmacy counter;

purchase requires proof of identification, and purchases are limited to a

maximum of 3.6 g of pseudoephedrine per

day.1 Despite this recent law,

methamphetamine manufacturers circumvent these restrictions by

“smurfing” or sending multiple people to make several pseudoephedrine

purchases at different retail centers.

Currently, most of the methamphetamine available in the USA is

produced domestically or in Mexico. Since the early 1980s, Mexican drug

cartels have trafficked both methamphetamine and its precursors into the

USA. Cartels in Mexico purchase bulk ephedrine or pseudoephedrine

from countries with less strict oversight of methamphetamine precursor

chemicals, such as India, Germany, and China. Despite efforts by both the

USA and the Mexican governments to prohibit the import of precursor

chemicals, methamphetamine production continues to

increase.1,8

Pathophysiology

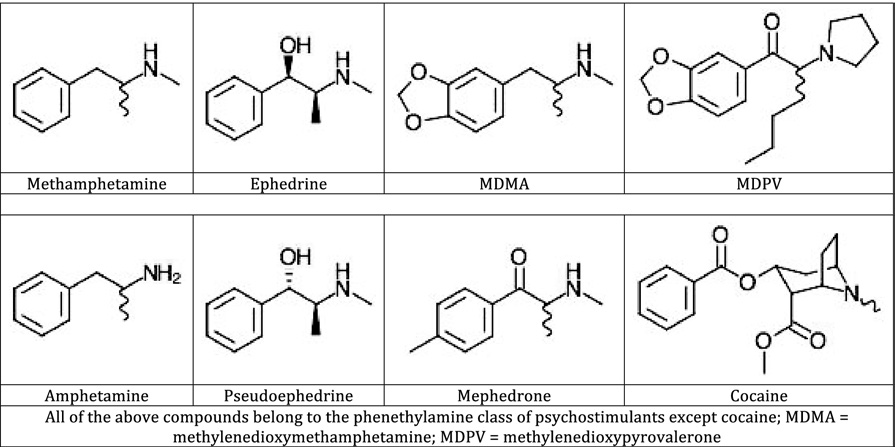

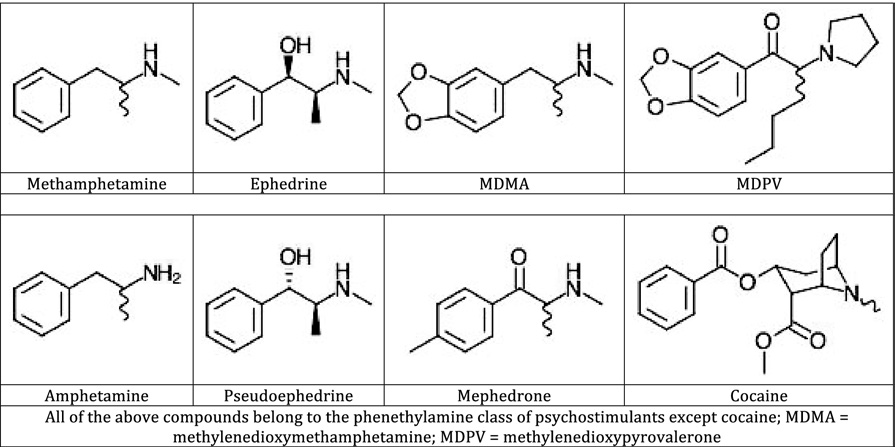

Methamphetamine is a member of the phenylethylamine class of

psychostimulants. Similar in structure to amphetamine, an added N-

methyl group confers added lipid solubility, allowing for more rapid

crossing of the blood– brain barrier

(Fig 1). This property of metham-

phetamine causes a higher ratio of central to peripheral action and a more

rapid onset of central

effects.9 The pathophysiology of methamphetamine

primarily relates to its effects on multiple neurotransmitter systems.

Dopamine (DA), a catecholamine, is the major neurotransmitter impacted

by methamphetamine use. However, methamphetamine also affects

serotonergic, noradrenergic, and glutamatergic systems as

well.10 The

acute adverse effects of such neurotransmitter dysregulation are predom-

inantly because of catecholamine excess. Specifically, this involves

cardiovascular activation via norepinephrine release from sympathetic

nerve endings as well as psychoactive stimulation from large quantities of

DA release into brain synapses, including the caudate, putamen, and

ventral striatal

regions.11,12 In contrast, chronic methamphetamine use

has been shown to cause persistent dopaminergic deficits.

DM, February 2012

45

link to page 10 link to page 38 link to page 39 link to page 39 link to page 39 link to page 39

FIG 1.

FIG 1. Structures of methamphetamine and selected other psychostimulants.

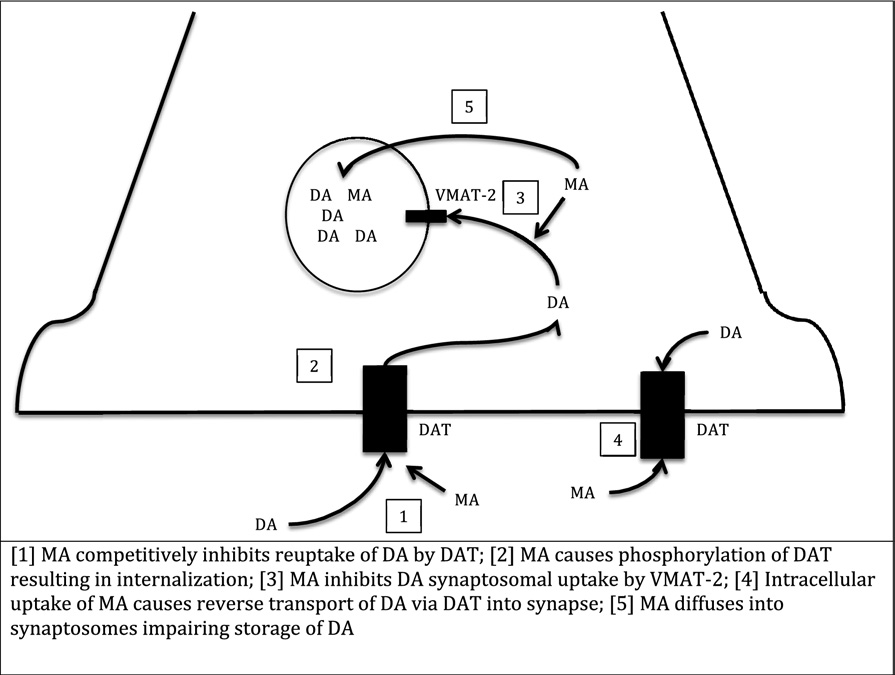

Methamphetamine’s main mechanism of action is its ability to increase

neuronal release of monoamines, particularly DA

(Fig 2). Much of this

release is mediated via alterations in both the plasmalemmal dopamine

transporter (DAT) and the vesicular monoamine transporter-2 (VMAT-2).

The function of VMAT-2 in normal cells is to sequester cytoplasmic DA

into vesicles for storage and subsequent release. As such, it is an

important regulator of cytoplasmic DA

levels.13 Methamphetamine inter-

feres with the function of VMAT-2, impairing its ability to store DA into

vesicles. This effect has been shown to occur in rats as early as 1 hour

post-administration using repeated, high doses of

methamphetamine.14

This mechanism is in contrast to other sympathomimetics that act as

synaptic reuptake inhibitors, such as cocaine or methylphenidate, where

DA uptake into vesicles is

increased.15,16 Both decreased vesicular

binding and decreased vesicular uptake of DA have been demonstrated in

the presence of

methamphetamine.17,18 These actions are believed to

occur via a subcellular redistribution of vesicles containing VMAT-2. In

the presence of methamphetamine, VMAT-2 relocates from a synapto-

somal to a nonsynaptosomal location within the

neuron.19 This relocation

impairs the neuron’s ability to sequester DA within vesicles for storage

and later deposition into the synapse.

In addition to VMAT-2, cytoplasmic DA levels are also highly

regulated by DAT. Under normal conditions, DAT clears extracellular

DA from the synaptic cleft back into the nerve terminal. This reuptake of

DA is then stored into synaptic vesicles via VMAT-2 for later release.

Evidence suggests that several factors impair the normal function of DAT

46

DM, February 2012

link to page 39 link to page 39 link to page 39 link to page 38

FIG 2.

FIG 2. Mechanism of action of methamphetamine on dopamine neurotransmission.

in the presence of methamphetamine. Phosphorylation of DAT via protein

kinase C occurs in response to methamphetamine, leading to internaliza-

tion of

DAT.20 Once internalized, DAT oligomers and higher molecular

weight DAT-associated protein complexes form, impairing the normal

function of

DAT.21,22 In a phosphorylation-independent mechanism,

methamphetamine also interferes with DAT reuptake of DA through

competitive

inhibition.23 Methamphetamine exists as an enantiomeric

mixture of d- and l-stereoisomers, with d-methamphetamine 3- to 10-fold

more potent at inhibiting DA reuptake via DAT than l-methamphet-

amine.13 Correspondingly, l-methamphetamine has minimal CNS effects,

whereas d-methamphetamine is the rotamer responsible for the euphoria

associated with methamphetamine abuse.

Concurrent with reuptake inhibition, methamphetamine also causes

efflux of DA into the synapse. Although the exact mechanism of this has

been debated, recent evidence suggests 2 distinct processes are involved.

Studies using amphetamine demonstrate a slow process in which amphet-

amine is transported intracellularly down its concentration gradient via

DAT in exchange for cytoplasmic DA. This transports DA out of the cell

and into the synapse in a reverse fashion through DAT compared with its

DM, February 2012

47

link to page 39 link to page 39 link to page 39 link to page 39 link to page 39 link to page 39 link to page 39

normal physiological role of DA reuptake. A second proposed mechanism

involves amphetamine inducing rapid millisecond bursts of release of

intracellular DA through DAT via a channel-like mechanism. Such a

process releases quantities of DA analogous to calcium-dependent exo-

cytosis of synaptic vesicles, and this may play a role in the psychostimu-

lant properties of

amphetamines.24 Presumably, similar mechanisms of

action occur with methamphetamine.

Synaptic DA release by methamphetamine is dependent on both

depletion of DA from vesicles and reversal of the physiological role of

DAT, with vesicular DA release being the rate-limiting

step.18,25 Impair-

ment of VMAT-2 causes relative elevations in cytoplasmic DA levels,

thus allowing transport of DA down its concentration gradient into the

synaptic cleft in the presence of methamphetamine. The chemical

properties of methamphetamine also contribute to such cytoplasmic DA

elevations. As a highly lipophilic molecule, methamphetamine freely

diffuses into nerve terminals and across vesicular membranes at high

concentrations to accumulate in synaptic vesicles. Further, as a weak

base, the accumulation of methamphetamine within these vesicles leads to

a disruption of the electrochemical gradient necessary for DA storage.

This consequently leads to elevated cytoplasmic DA concentrations and

eventual reverse transport through DAT into the

synapse.18,26

In contrast to the acute effects of increased synaptic DA efflux, repeated

high-dose administration of methamphetamine has been demonstrated to

cause persistent dopaminergic deficits in both animals and humans.

Through methamphetamine-induced aberrant cytosolic DA accumulation,

DA-associated reactive oxygen species are formed and believed to

contribute to this

depletion.18 Methamphetamine-associated reactive ox-

ygen species cause eventual activation of the Jun N-terminal kinase/

stress-activated protein kinase (JNK/SAPK) pathway, leading to neuronal

apoptosis.27 Deficits in DA nerve terminal markers (including decreases

in DA, DAT, and tyrosine hydroxylase) have been demonstrated in

postmortem studies of human

striatum.28,29 PET studies have also shown

significant loss of striatal DAT in chronic methamphetamine users.

Although abstinence has been reported to lead to some recovery in DAT,

particularly in the caudate and putamen regions, this has not been reported

to correlate with functional cognitive recovery on neuropsychological

testing.30,31 These fundamental changes underlie the neurotoxic effects

believed to cause persistent dopaminergic deficits in chronic abusers.

Chronic methamphetamine abuse has been reported to result in histo-

pathological changes in the brain. Chronic methamphetamine abuse leads

to gray- and white-matter density changes and altered concentrations of

48

DM, February 2012

link to page 40 link to page 40 link to page 40 link to page 40 link to page 40 link to page 41 link to page 41 link to page 41 link to page 41 link to page 41 link to page 41 link to page 41

metabolites in the frontal gray and white matter and anterior cingulated

gray matter that are dose-dependent and that may only be partially

reversible with

abstinence.32-36 Damage to striatal dopamine and fore-

brain serotonin terminals and degeneration of somatosensory cortical

neurons have been demonstrated in

rats.37 One of the mechanisms

thought to be responsible is methamphetamine-induced dopamine release,

resulting in reactive oxygen species, causing striatal neurotoxicity,

caspase-dependent apoptosis, and glial

activation.38-44 Advanced age and

male gender may be risk factors for more pronounced neuronal damage,

perhaps because of increased susceptibility to damage from reactive

oxygen species and the lack of protective effects of estrogen, respecti-

vely.45-47 The degree of degeneration of frontal gray- and white-matter

integrity and frontal white-matter hypometabolism has been reported to

correlate with poor performance on some neuropsychological

tests.33,47,48

Chronic methamphetamine abuse causes histopathological changes to

cardiac myocytes. Treatment of rats with methamphetamine over a period

of weeks has been reported to cause subendocardial myocytic degenera-

tion and necrosis followed by extensive myocytic degeneration, necrosis,

and

fibrosis.49 Electron microscopy of these lesions shows degeneration

of the

mitochondria.50,51 Other histopathological lesions associated with

methamphetamine abuse include myocyte hypertrophy with disorganiza-

tion of myofibrils, microtubules, and actin

structures.52 Histopathological

cardiomyocyte changes are associated with release of lactate dehydroge-

nase and creatine phosphokinase, 2 markers of cardiomyocyte damage.

Additionally, this damage may occur in the presence or absence of

beta-blockade, suggesting that methamphetamine is directly myotoxic in

addition to the toxicity that may result from sympathetic overstimula-

tion.53-55 Some of these histopathological changes may be gradually or

partially reversible following discontinuation of the

drug.56 The histo-

pathological lesions seen with chronic methamphetamine abuse are

consistent with lesions seen in cardiomyopathy and may explain the

development of cardiomyopathy in chronic methamphetamine

abusers.57

Adverse Health Effects of Methamphetamine

Abuse

Cardiovascular

Chest pain is a common complaint associated with methamphetamine

administration. Chest pain accounts for 38% of emergency department

visits and 28% of admissions in methamphetamine-intoxicated

patients.58

Tachycardia and hypertension are common clinical findings in metham-

DM, February 2012

49

link to page 41 link to page 41 link to page 41 link to page 41 link to page 42 link to page 41 link to page 42 link to page 42 link to page 41 link to page 42 link to page 42 link to page 42

phetamine

intoxication.59 Although in some patients, chest pain is due

solely to methamphetamine-induced hypertension and tachycardia or

anxiety, acute coronary syndrome (ACS) is common among methamphet-

amine users and patients with chest pain in the context of methamphet-

amine abuse should be evaluated for

ACS.60

In 1 small series of patients presenting to an emergency department with

chest pain after methamphetamine use, 25% were found to have ACS and

8% suffered a cardiac complication, including ventricular fibrillation,

ventricular tachycardia, and supraventricular

tachycardia.61 Putative

mechanisms for myocardial infarction in the setting of methamphetamine

abuse include accelerated atherosclerosis, rupture of preexisting athero-

sclerotic plaques, hypercoaguability, and epicardial coronary artery

spasm.62,63 Methamphetamine abusers have significantly higher rates of

coronary artery disease than the

public.64 Even patients with normal

coronary arteries are at risk for methamphetamine-induced myocardial

infarction because of coronary spasm, which may be refractory to

intracoronary vasodilator

therapy.63 Acute myocardial infarction follow-

ing methamphetamine use may be severe, resulting in cardiogenic shock

and

death.65

Methamphetamine is also associated with cardiac dysrhythmias. In 1

case series of methamphetamine-intoxicated patients, a prolonged

corrected QT interval (QTc ⬎440 ms) was found in 27.2% of

participants, suggesting that methamphetamine-induced alterations in

cardiac conduction may be partly responsible for its dysrhythmogenic

effects.66 Premature ventricular contractions, premature supraventric-

ular contractions, accelerated atrioventricular conduction, atrioven-

tricular block, intraventricular conduction delay, bundle branch block,

ventricular tachycardia, ventricular fibrillation, and supraventricular

tachycardia all have been reported in the setting of methamphetamine

intoxication.55,61,66 Methamphetamine-induced dysrhythmias may

also occur because of myocardial ischemia or infarction.

Methamphetamine abuse is associated with an acute dilated cardiomy-

opathy with global ventricular dysfunction. This cardiomyopathy occurs

in the absence of cardiac ischemia or infarct as measured by nuclear

myocardial perfusion study and in the absence of coronary stenosis as

measured by cardiac

catheterization.67 Methamphetamine-associated car-

diomyopathy may result in acute cardiogenic pulmonary edema and may

be

reversible.65,68,69 Several putative mechanisms by which methamphet-

amine may induce cardiomyopathy include recurrent coronary artery

spasm, small vessel disease, or diffuse myocardial toxicity because of

overstimulation of cardiac adrenergic

receptors.67 Methamphetamine-

50

DM, February 2012

link to page 42 link to page 42 link to page 42 link to page 42 link to page 42 link to page 42 link to page 42 link to page 41 link to page 42 link to page 42 link to page 42

induced cardiomyopathy has been reported to resemble transient apical

ballooning syndrome (previously known as Takotsubo cardiomyopathy),

a specific cardiomyopathy caused by transient left ventricular dysfunction

thought to be linked to excessive

catecholamines.70

Methamphetamine use may be associated with aortic dissection, likely

because of its hypertensive effects resulting in increased wall shear

stress.71 Methamphetamine appears to carry a greater risk for aortic

dissection than cocaine and may be second only to hypertension in its

importance as a risk factor for aortic

dissection.72 Aortic dissection

associated with methamphetamine abuse is also associated with cardiac

tamponade and sudden

death.73

Intravenous methamphetamine abuse has been associated with endocar-

ditis. As with other intravenous drugs of abuse, methamphetamine-

associated infective endocarditis is frequently right-sided and may result

in

death.74,75

Dermatologic

Methamphetamine abuse predisposes to repetitive, stereotypical skin-

picking, resulting in excoriations on the face and

extremities.76 In some

cases, skin picking may be related to methamphetamine-induced formi-

cation or delusions of

parasitosis.77 Both skin-picking and the use of

nonsterile needles in intravenous methamphetamine abusers may result in

skin and soft-tissue infections. In 1 series of methamphetamine abusers

presenting to an emergency department, skin infection accounted for 6%

of emergency department visits and 54% of subsequent admissions to the

hospital. Methamphetamine-related skin infections may take the form of

cellulitis or cutaneous

abscess.58

Hematological

Methamphetamine users may have a higher risk of contracting human

immunodeficiency virus (HIV) because of unsafe sex practices or use of

contaminated needles during methamphetamine administration. Metham-

phetamine users have been reported to be more likely to engage in risky

sexual behaviors than nonusers. Men who have sex with men (MSM),

heterosexual men, and heterosexual women who use methamphetamine

report more sexual partners than nonusers and more casual or anonymous

sex

partners.78 Methamphetamine users are more likely to participate in

sexual activities that confer a higher risk of HIV transmission, such as

anal sex and sex with known injection drug users, and are less likely to

use condoms during vaginal and anal

intercourse.79 Additionally, meth-

amphetamine use is associated with paying for or being paid for

sex.79

DM, February 2012

51

link to page 42 link to page 42 link to page 42 link to page 42 link to page 42 link to page 43 link to page 43 link to page 43 link to page 43 link to page 43 link to page 43

Methamphetamine use is associated with a higher risk of sexual HIV

infection.79 The use of contaminated needles is another source of HIV

infection in methamphetamine users. As with other intravenous drugs of

abuse, the sharing of needles and the corresponding risk of contracting a

blood-borne disease, including HIV, is not

uncommon.80

Methamphetamine abuse is associated with necrotizing angiitis. Histo-

logic features include fibrinoid necrosis of the intima and media of blood

vessels with destruction of vascular smooth muscle.

81,82 Macroscopically,

affected arteries display segmental narrowing with aneurysm formation,

resulting in a “beaded”

appearance.81 Drug-induced necrotizing angiitis

may result in target organ damage to the heart, brain, liver, kidney, bowel,

and pancreas with clinical manifestations of myocardial infarction,

ischemic or hemorrhagic stroke, renal failure, hepatic necrosis, bowel

infarction, and pancreatitis, among

others.83,84

Gastrointestinal

Methamphetamine users are at higher risk for contracting viral hepatitis

than nonusers because of risky sexual behavior and the use of contami-

nated needles. Methamphetamine users are more likely to be infected with

hepatitis A and B than nonusers and, among methamphetamine users,

injection users have a higher prevalence of both diseases than noninjec-

tion

users.85 Use of contaminated needles puts methamphetamine users at

particular risk for hepatitis C infection, although hepatitis C infection is

also more common among methamphetamine users who smoke or

insufflate the drug than it is in the general

population.86,87

Even in the absence of viral hepatitis, methamphetamine abuse has been

reported to cause acute liver injury with hepatic necrosis and centrilobular

degeneration.88 Additionally, methamphetamine enhances the hepatic

toxicity of other agents, such as carbon tetrachloride. Although the cause

of the hepatic injury is unclear, it has been proposed that an adrenore-

ceptor-related mechanism or stimulation of Kupffer cells may be respon-

sible.89,90

Mesenteric infarction requiring total proctocolectomy and resection of

the ileum and jejunum has been reported following methamphetamine use

with microscopic examination showing changes consistent with acute

vasculitis.91 Segmental ischemic colitis in the absence of thrombosis,

vasculitis, or vasospasm with spontaneous resolution has also been

reported.92 Methamphetamine may cause mesenteric ischemia or infarc-

tion by several mechanisms, including necrotizing vasculitis, cardiovas-

cular shock, sympathomimetic vasospasm, or splanchnic vasoconstric-

52

DM, February 2012

link to page 43 link to page 43 link to page 42 link to page 43 link to page 43 link to page 43 link to page 43 link to page 17 link to page 43 link to page 44 link to page 44 link to page 44

tion.93-95 It remains unclear how important each of these mechanisms is

to methamphetamine-induced mesenteric infarction.

Severe acute necrotic hemorrhagic pancreatitis has been reported in

cases of sudden death in chronic methamphetamine abusers. Histopathol-

ogy studies of the effect of chronic methamphetamine abuse on pancreatic

tissues suggest that methamphetamine may cause regional hemorrhage,

acinal cell death, and fibrosis possibly because of tissue hypoxia or

necrotizing

angiitis.96,97

Genitourinary

Methamphetamine users are more likely to be diagnosed with a sexually

transmitted disease (STD) than nonusers because of an increased likeli-

hood of engaging in risky sexual

behaviors.78,79 Prolonged sex while on

methamphetamine can lead to chafing or soft-tissue injury to the genitals

with correspondingly higher risk of transmission of an STD or blood-

borne infection.

98 Injection methamphetamine abusers have a higher

prevalence of STD infections than noninjection methamphetamine abus-

ers.99 Among methamphetamine-dependent gay men, an elevated preva-

lence of chlamydia, syphilis, and genital and oral gonorrhea has been

reported with a lifetime prevalence of genital gonorrhea of 40%. Psychi-

atric comorbidity may be associated with a higher prevalence of STD

infection in methamphetamine-dependent individuals.

100 In 1 study in

Thailand, methamphetamine users were reported to have higher rates of

chlamydial infection than opiate

users.101

Musculoskeletal

Perhaps the most publicized adverse health effect of methamphetamine

abuse, by both governmental agencies and the lay media, is “meth mouth”

(Fig 3).102,103 Methamphetamine induces dental decay through multiple

mechanisms, including xerostomia from sympathetic overstimulation and

bruxism, resulting in multiple dental

caries.104,105 Also of concern is the

consumption of large quantities of sugared soft drinks in an attempt by the

user to resolve the xerostomia and lack of oral hygiene during extended

periods of drug

abuse.106,107 Although dental decay because of metham-

phetamine abuse is well documented, 1 study found that the degree of

dental decay in methamphetamine users as compared to other substance

users in an inpatient chemical dependency treatment unit was similar,

suggesting that at least some of the dental decay associated with

methamphetamine abuse is due to factors common to substance abuse in

general, such as poor personal hygiene and

malnutrition.108

DM, February 2012

53

link to page 44 link to page 41 link to page 44 link to page 44

FIG 3.

FIG 3. “Meth mouth.” Severe dental caries because of methamphetamine abuse. (Reprinted

with permission from Hamamoto DT, Rhodus NL. Methamphetamine abuse and dentistry. Oral

Dis 2009;15:27-37.) (Color version of figure is available online.)

Methamphetamine abuse is also associated with rhabdomyolysis. In 1

series of patients presenting to an emergency department with rhabdo-

myolysis, 43% had urine drug immunoassays positive for methamphet-

amine. Methamphetamine-induced rhabdomyolysis may be due to psy-

chomotor agitation or

seizures.109

Methamphetamine-intoxicated patients are at increased risk for trau-

matic injury. In 1 case series of methamphetamine-positive patients

presenting to an emergency department, the most common chief com-

plaint was blunt trauma, accounting for 33% of emergency department

visits and 74% of subsequent

admissions.58 Among a case series of

consecutive trauma patients, methamphetamine was the most commonly

used illicit drug. Trauma patients with positive urine drug immunoassays

for methamphetamine are more likely to suffer from violent mechanisms

of injury, including assault, gunshot wound, and stabbing than trauma

patients testing negative for methamphetamine. They are also more likely

to have attempted suicide, be a victim of domestic violence, or have an

altercation with law

enforcement.110,111 Methamphetamine users have

also been reported to be more likely to have severe injuries, to leave

against medical advice, and to die from their

injuries.110,112

Pott’s puffy tumor (osteomyelitis of the frontal bone) has been associ-

ated with intranasal methamphetamine use. Local methamphetamine-

induced ischemic injury to the sinus mucosa is thought to produce an

54

DM, February 2012

link to page 44 link to page 44 link to page 44 link to page 42 link to page 42 link to page 44 link to page 42 link to page 44 link to page 44 link to page 44 link to page 43 link to page 44 link to page 41 link to page 45

environment conducive to the development of frontal bone osteomyelitis

and subperiosteal

abscess.113

Neurological

Methamphetamine is associated with many neurological adverse health

effects, although the most devastating is intracranial hemorrhage. Meth-

amphetamine-induced hypertension and tachycardia may lead to intracra-

nial hemorrhage, in patients with or without preexisting cerebrovascular

disease.114 Methamphetamine may be more toxic than cocaine in induc-

ing intracranial hemorrhage, possibly because of its more prolonged

cardiovascular

effects.115 Methamphetamine-induced necrotizing angiitis

may also play a role in methamphetamine-associated intracranial hemor-

rhage with fibrinoid necrosis of the intima and media of vessels

predisposing to vessel

rupture.81,116,117 Intraparenchymal bleeds in the

cerebrum, cerebellum, corpus callosum, basal ganglia, and brainstem

have been reported and may result in

death.81,114,116-119 Fatal intraven-

tricular hemorrhages have also been

reported.120 A number of intracranial

berry aneurysm ruptures related to methamphetamine intoxication have

been reported, frequently with fatal

results.73,115 Subarachnoid hemor-

rhage in the absence of berry aneurysm or arteriovenous malformation

has also been

reported.117

Methamphetamine abuse is also associated with ischemic

stroke.119,121-123

As with intracranial hemorrhage, methamphetamine-induced hyper-

tension, tachycardia, and necrotizing angiitis may contribute to the

development of ischemic

stroke.121 For intravenous methamphetamine

use, fillers, such as talc, may also contribute to ischemic or hemorrhagic

stroke.94 Methamphetamine-induced ischemic stroke may occur in the

absence of evidence of chronic hypertension or cerebral vasculopa-

thy.117,119

Methamphetamine intoxication also causes seizure. Methamphetamine-

induced seizures may occur in persons with or without any past medical

history of seizure disorder. In 1 series of methamphetamine-intoxicated

patients presenting to an emergency department, 7% of patients with

altered level of consciousness had tonic-clonic seizure and, of those

patients, 75% had no previous history of

seizure.58 Limited evidence

suggests that chronic methamphetamine exposure may lower the seizure

threshold more than a single acute

exposure.124

Methamphetamine abuse also results in cognitive impairment, which

may be persistent. Current methamphetamine users have impaired per-

formance on tests of memory, the ability to manipulate information,

attention, and abstract thinking as compared to matched controls, al-

DM, February 2012

55

link to page 45 link to page 45 link to page 38 link to page 45 link to page 45 link to page 45 link to page 45 link to page 45 link to page 45 link to page 45 link to page 45 link to page 45 link to page 45

though they showed no impairment in psychomotor speed, intelligence, or

verbal fluency. Heavier methamphetamine users have greater cognitive

impairment than less frequent

users.125 Methamphetamine may selec-

tively impair visual memory more than verbal memory, perhaps

because of executive function

damage.126 Conversely, at low admin-

istered doses, some studies have reported that single doses of

methamphetamine may improve reaction times, cognitive perfor-

mance, and verbal

memory.10,127

Following methamphetamine abstinence of 1-2 weeks, chronic

methamphetamine abusers show persistent impairment on neurocog-

nitive measures of attention, psychomotor speed, verbal learning and

memory, and executive system

measures.128 Following prolonged

methamphetamine abstinence (mean abstinence of 20 months),

chronic methamphetamine abusers still display impaired attentional

control that may be related to changes in neurochemicals in frontos-

triatal brain regions and to microstructural changes in the white matter

of the corpus

callosum.129,130

Patients with HIV or hepatitis C may be particularly at risk for

developing cognitive impairment because of methamphetamine abuse.

Hepatitis C infection augments methamphetamine-induced cognitive

deficits in the areas of learning, abstraction, and motor skills as well

as global neuropsychological

impairment.131 HIV similarly interacts

with methamphetamine to produce cognitive

deficits.132 HIV-positive

chronic methamphetamine users display additional neuronal injury

and glial activation in the frontal cortex and basal ganglia as compared

to HIV-negative methamphetamine

users.133 This effect is amplified in

patients with high HIV viral

loads.134 A combination of methamphet-

amine and HIV proteins has been implicated in causing significant

neuronal toxicity, possibly by activating caspase-dependent cell death

pathways leading to neuronal

apoptosis.135-137

Rarely, methamphetamine abuse has been associated with choreoathe-

tosis. This may be due to central dopaminergic effects of methamphet-

amine and has been reported only in the setting of acute methamphet-

amine

intoxication.138,139 Other reported neurological sequelae of

methamphetamine intoxication include photophobia and

ataxia.140

Ophthalmologic

Acute unilateral vision loss has been reported following intranasal

methamphetamine abuse. The vision loss is believed to be due to ischemic

optic neuropathy secondary to methamphetamine-induced vasospasm and

methamphetamine-associated

vasculitis.141,142

56

DM, February 2012

link to page 46 link to page 46 link to page 42 link to page 46 link to page 46 link to page 41 link to page 43 link to page 46 link to page 46 link to page 46 link to page 46 link to page 46 link to page 46 link to page 46 link to page 46

Psychiatric

Methamphetamine abuse is associated with psychiatric disease. Meth-

amphetamine intoxication is associated with restlessness, insomnia,

hallucinations, paranoia, and disturbance of

consciousness.143 Abstinence

following methamphetamine intoxication is associated with depression,

anhedonia, irritability, and poor concentration, although these symptoms

are frequently mild and transient.

144 Methamphetamine users are more

likely to carry a psychiatric diagnosis and be prescribed psychiatric

medications than cocaine

users.80

Chronic methamphetamine abuse is associated with depressive symp-

toms and suicidal ideation.

145,146 Among adolescent methamphetamine

users, 16% reported suicidal

ideation.147 Suicide attempts during meth-

amphetamine intoxication are common and may involve overdose, slash

wounds to the extremities, and jumps from

heights.58,148 In methamphet-

amine-dependent gay men, 25% report a history of at least 1 suicide

attempt.

100 In 1 series of completed youth suicides, alcohol and metham-

phetamine were the most common substances found in the

blood.149 Risk

factors for methamphetamine-related suicide attempt include female

gender, intravenous methamphetamine use, history of methamphetamine-

induced psychosis, methamphetamine-induced depressive disorder, and

family history of psychotic disorders.

150,151

Methamphetamine abuse may be associated with self-injurious behavior

and self-mutilation. Methamphetamine-intoxicated individuals may be

motivated by bizarre religious, sexual, or neurotic thoughts and self-

mutilation may take a variety of forms, such as eye enucleation or genital

self-mutilation.152 In some chronic methamphetamine abusers, self-

mutilation may be recurrent or

severe.153

Chronic methamphetamine abuse may result in psychosis with predom-

inant auditory hallucinations, persecutory delusions, delusions of refer-

ence, and pathologic hostility.

154-157 Methamphetamine-induced psycho-

sis mimics paranoid schizophrenia and patients with either disease have

been found to have similar deficits in neurocognitive

functioning.158 In 1

sample of methamphetamine abusers, 13% screened positive for psycho-

sis, whereas another 23% had at least 1 psychotic symptom (eg,

unusual thought content). Dependent methamphetamine abusers were

3 times more likely to have psychotic symptoms than nondependent

abusers, and the prevalence of psychosis in methamphetamine abusers

was reported to be 11 times higher than in the general

population.159

In Thailand, 10% of psychiatric hospital admissions are for metham-

phetamine-related

psychosis.160

DM, February 2012

57

link to page 46 link to page 47 link to page 46 link to page 47 link to page 42 link to page 47 link to page 47 link to page 47 link to page 47 link to page 47 link to page 43

Chronic methamphetamine abuse results in behavioral sensitization to

the drug where even small doses may then trigger a relapse of the

psychosis and the duration of vulnerability to relapse progressively

becomes

longer.161,162 Although in some patients methamphetamine

psychosis may be transient, in others psychosis may persist despite

months of abstinence and be resistant to antipsychotic

medications.163

Young age at onset of methamphetamine abuse, heaviness of metham-

phetamine abuse, schizoid or schizotypal personality disorder, and history

of preexisting neurological disorder (eg, learning disorder or attention-

deficit/hyperactivity disorder) are risk factors for the development of

persistent methamphetamine-induced

psychosis.155,164 In addition, the

extent of neuronal damage in the basal ganglia correlates with severity of

psychiatric

symptoms.165

Pulmonary

Acute noncardiogenic pulmonary edema may occur after smoking

methamphetamine despite normal pulmonary artery and pulmonary

wedge pressures. Respiratory failure and hypotension requiring mechan-

ical ventilation and vasopressor support have been reported and have been

reported to be

reversible.68

Methamphetamine is strongly associated with idiopathic pulmonary

arterial hypertension

(PAH).166 Methamphetamine intoxication has been

shown to cause an acute rise in pulmonary arterial

pressures.167 Although

the role methamphetamine plays in inducing PAH remains unclear,

proposed mechanisms include toxic endothelial injury, hypoxic insult,

direct spasm, vasculitis, and dysregulation of vascular

tone.168 One

favored hypothesis is that methamphetamine induces PAH by the same

mechanism as fenfluramine, through interaction with serotonin transport-

ers resulting in serotonin

release.169

An additional concern in methamphetamine-induced PAH is the use of

outpatient intravenous therapy. In severe cases of PAH, continuous

epoprostenol or treprostinil infusions may be indicated and infused in the

outpatient setting through an indwelling central intravenous catheter. Use

of such indwelling catheters in methamphetamine users may be compli-

cated by homelessness, inability to properly care for the catheter, or

infection because of the patient accessing the catheter to administer illicit

drugs.170

Renal

Acute renal failure may be reported following methamphetamine abuse

and may be due to myoglobinuria, hypotension, or necrotizing

angiitis.91

58

DM, February 2012

link to page 44 link to page 43 link to page 47 link to page 47 link to page 47 link to page 47 link to page 47 link to page 47 link to page 47 link to page 48 link to page 48 link to page 48 link to page 48 link to page 48

Myoglobinuric renal failure because of methamphetamine-associated

rhabdomyolysis is frequently self-limited, although hemodialysis may be

temporarily necessary. Rarely, methamphetamine-associated myoglobin-

uric renal failure may be persistent, resulting in end-stage renal dis-

ease.109 Methamphetamine-associated necrotizing angiitis has also been

associated with renal insufficiency culminating in end-stage renal disease

requiring

hemodialysis.84

Obstetrical

Methamphetamine is increasingly a drug of choice among substance-

dependent pregnant

women.171 Methamphetamine abuse during preg-

nancy is concerning both for the risk of adverse pregnancy outcome and

for possible damage to the developing fetus. Methamphetamine abuse is

also associated with perinatal maternal death and has been implicated as

a possible contributing factor to amniotic fluid embolism.

Several adverse pregnancy outcomes have been associated with prenatal

maternal methamphetamine use. Methamphetamine use is associated with

fetal growth restriction and premature

delivery.172-175 Placental insuffi-

ciency, hemorrhage, and abruption have also been associated with

maternal methamphetamine

abuse.175,176 Prenatal methamphetamine ex-

posure is thought to put a fetus at higher risk for intraventricular

hemorrhage and cavitary lesions in the

brain.175 Additionally, maternal

methamphetamine abuse is associated with inadequate prenatal

care.177

Prenatal exposure to methamphetamine has been suggested to increase

the risk for adverse postnatal outcomes. Prenatal methamphetamine

exposure has been linked to neonatal neurobehavioral outcomes of

decreased arousal, increased physiological stress, and poor quality of

movement in a dose–response

relationship.178,179 Prenatal methamphet-

amine exposure has been reported to cause neonatal toxic hepatitis with

cholestasis.180 Children with prenatal methamphetamine exposure have

been noted to have structural and chemical brain differences as compared

to healthy controls and structural differences correlate with poorer

performance on attention and verbal memory

tests.181,182 Animal studies

have also suggested that prenatal methamphetamine exposure may

adversely affect the myelination

process.183 Rats exposed prenatally to

methamphetamine are reported to have lower seizure threshold, lower

birth weights, and impaired sensory-motor

coordination.184,185 Rat stud-

ies have also suggested that some methamphetamine-related deficits, such

as sensory-motor correlation, may affect 2 generations of

offspring.186

Although methamphetamine has been reported to be teratogenic in animal

studies, no human studies have confirmed this

effect.187,188

DM, February 2012

59

link to page 48 link to page 48 link to page 48 link to page 48 link to page 48 link to page 48 link to page 48 link to page 48

Exploratory Methamphetamine Exposure in Children

Inadvertent pediatric exposure to methamphetamine may be increasing.

In 1 series of methamphetamine-dependent patients presenting for drug

rehabilitation, 44% had children in their home. Of children found in

methamphetamine laboratories by police or child protective services, 45%

have a positive hair specimen for 1 or more illicit drugs with the most

common positive result being

methamphetamine.189 Common signs and

symptoms of methamphetamine poisoning in the pediatric population

include tachycardia, agitation, inconsolable crying, irritability, and vom-

iting. Rhabdomyolysis is a common complication.

190,191 Seizure is a less

common symptom of pediatric methamphetamine

poisoning.191 Transient

cortical blindness secondary to methamphetamine poisoning has been

reported in an

infant.192 Pediatric methamphetamine poisoning may be

difficult to distinguish from scorpion envenomation, resulting in unnec-

essary exposure to

antivenom.190,193

Children may also be at risk of traumatic injury or abuse because of

parental behaviors while using methamphetamine. Parental supervision

while on a methamphetamine binge may be lax and caregivers may sedate

their children with benzodiazepines or diphenhydramine while engaging

in methamphetamine abuse. In addition, children in homes where meth-

amphetamine is abused are reported to be at higher risk for exposure to

age-inappropriate material, such as pornography.

189

Methamphetamine-Associated Death

Methamphetamine abuse may be directly or indirectly fatal. Direct

methamphetamine-related mortality is frequently due to catastrophic

neurological or cardiac complications, while indirect methamphetamine-

related deaths are frequently traumatic in nature. In 1 series of metham-

phetamine-related fatalities, the cause of death was categorized as natural,

accidental, suicidal, homicidal, or uncertain in 13%, 59%, 11%, 14%, and

3% of cases, respectively. In another series, homicide and suicide

accounted for 27% and 15% of methamphetamine-related fatalities,

respectively.194 In a series of autopsies in methamphetamine-positive

patients, the most common cause of death was multiorgan system

dysfunction, followed by cardiovascular or cerebrovascular disease,

traumatic shock, asphyxiation, and

exsanguination.195

Methamphetamine-related fatalities constitute a significant public

health problem in areas where methamphetamine abuse is prominent: in

Taiwan, 12.1% of all autopsy cases in 1 year were related to metham-

60

DM, February 2012

link to page 48 link to page 48 link to page 48 link to page 48 link to page 49 link to page 49 link to page 44 link to page 49 link to page 42 link to page 42 link to page 49 link to page 48 link to page 49

phetamine. Males may be more likely to suffer methamphetamine-related

death than

females.195,196

Concomitant abuse of another drug, eg, cocaine or ethanol, has been

identified as a factor in some methamphetamine-related fatalities and

varies in frequency depending on cultural

norms.197 Although animal

studies have suggested that concomitant ethanol ingestion is protective

against some of the toxic effects of methamphetamine, ethanol intoxica-

tion may simultaneously increase the risk of accidental or traumatic

death.198

A frequently reported cause of direct methamphetamine-related fatality

is multisystem organ failure secondary to methamphetamine toxicity,

which is characterized by hyperthermia, pulmonary congestion, coma,

shock, hyperthermia, acute renal failure, metabolic acidosis, and hyper-

kalemia.195,198-200 As with other illicit drugs, body packers and body

stuffers are at risk for death in the event of package

rupture.201-203

Methamphetamine-induced agitation and hyperactivity can cause death

secondary to metabolic acidosis and

hyperthermia.204

Intracranial hemorrhage is a commonly reported neurological compli-

cation of methamphetamine abuse resulting in

death.118 Methamphet-

amine-related status epilepticus may also contribute to

death.202 Cardiac

complications of methamphetamine abuse that are frequently reported to

result in death include arrhythmia and acute myocardial

infarction.65,66

Methamphetamine-related hypertension and tachycardia may cause sud-

den death because of berry aneurysm rupture or aortic dissection with

cardiac

tamponade.73

Indirect methamphetamine-related fatalities are frequently traumatic

and may be due to accident, assault, or

suicide.205 Methamphetamine-

related traffic deaths could result from riskier driving behavior while

intoxicated, and blood amphetamine concentration is positively correlated

to traffic-related

impairment.194,206,207 In 1 study of traffic-related fatal-

ities, methamphetamine was found in the blood of 5% of fatally injured

drivers.208

Methamphetamine Abuse-Associated Toxicologic

Exposures

Most reported toxicologic exposures because of methamphetamine are

in the context of production of methamphetamine, discussed below.

However, methamphetamine abuse has been linked to acute lead poison-

ing. Depending on the method of synthesis used, methamphetamine

manufacture may involve lead acetate. Lead poisoning due to metham-

phetamine abuse may be due to a high lead content in the drug because

DM, February 2012

61

link to page 49 link to page 49 link to page 49 link to page 38 link to page 38 link to page 49 link to page 49

of inadequate processing during manufacture or deliberate contamina-

tion.209 In 1 outbreak of methamphetamine-associated lead poisoning, 14

confirmed cases occurred in 1 year because of intravenous use of a batch

of methamphetamine that was 60% lead by

weight.210 However, lead

poisoning is not thought to be widespread among methamphetamine users

and may occur only episodically with batches of contaminated

drug.211

Current Trends

Domestic Trends

Several agencies collect data useful in identifying trends in metham-

phetamine use. A frequent limitation in these data sets is the inclusion of

methamphetamine in a general category labeled “non-cocaine stimu-

lants,” making it difficult to track trends in methamphetamine as opposed

to trends in stimulant abuse in general. Examples of national data sources

include the National Survey on Drug Use and Health, Monitoring the

Future, Youth Behavior Risk Surveillance System, Treatment Episode

Data Set, Drug Abuse Warning Network, Substance Abuse and Mental

Health Services Administration, and Arrestee Drug Abuse Monitoring

system.1

A 2004 report issued by Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services

Administration estimates that, in 2004, 12 million or 2.9% of the US

population aged 12 years or older have tried methamphetamine in their

lifetime; 1.4 million used it in the past year, and 600,000 used it in the

past month. The highest rates of past year methamphetamine use were

found among Native Hawaiians or Pacific Islanders (2.2%) and American

Indians or Alaska Natives (1.7%), whereas lower rates of past year use

were found among whites (0.7%), Hispanics (0.5%), blacks (0.1%), and

Asians

(0.2%).1 Another survey estimates rates of past year methamphet-

amine use among persons aged 12 or older were highest in Nevada

(2.0%), Montana (1.5%), and Wyoming (1.5%), while the lowest rates

were in Connecticut, Maryland, Massachusetts, New Jersey, and New

York.212-214 The highest rates of amphetamine- or methamphetamine-

related emergency department visits are reported in San Francisco,

Seattle, San Diego, and Los Angeles. In the 2002 Drug Abuse Warning

Network database, white patients were responsible for 65% of amphet-

amine- or methamphetamine-related emergency department visits; 58%

of visits were men, and most visits involved patients aged 18-34

years.215,216

Subpopulations at disproportionate risk for methamphetamine use

reportedly include criminal offenders and MSM. Currently, men and

62

DM, February 2012

link to page 38 link to page 49 link to page 27 link to page 49 link to page 50 link to page 50

women abuse methamphetamine equally, unlike many other illegal drugs

where there is a male predominance among abusers. Methamphetamine

abusers frequently engage in criminal and/or violent behavior and many

have been involved with the criminal justice system.

Among MSM, methamphetamine abuse is associated with high-risk

sexual behaviors. Methamphetamine is increasingly abused by MSM

while engaging in sexual activity, termed “party and play” or “PnP,” and

abuse is common in sex clubs and “circuit

parties.”1,8,217 The number of

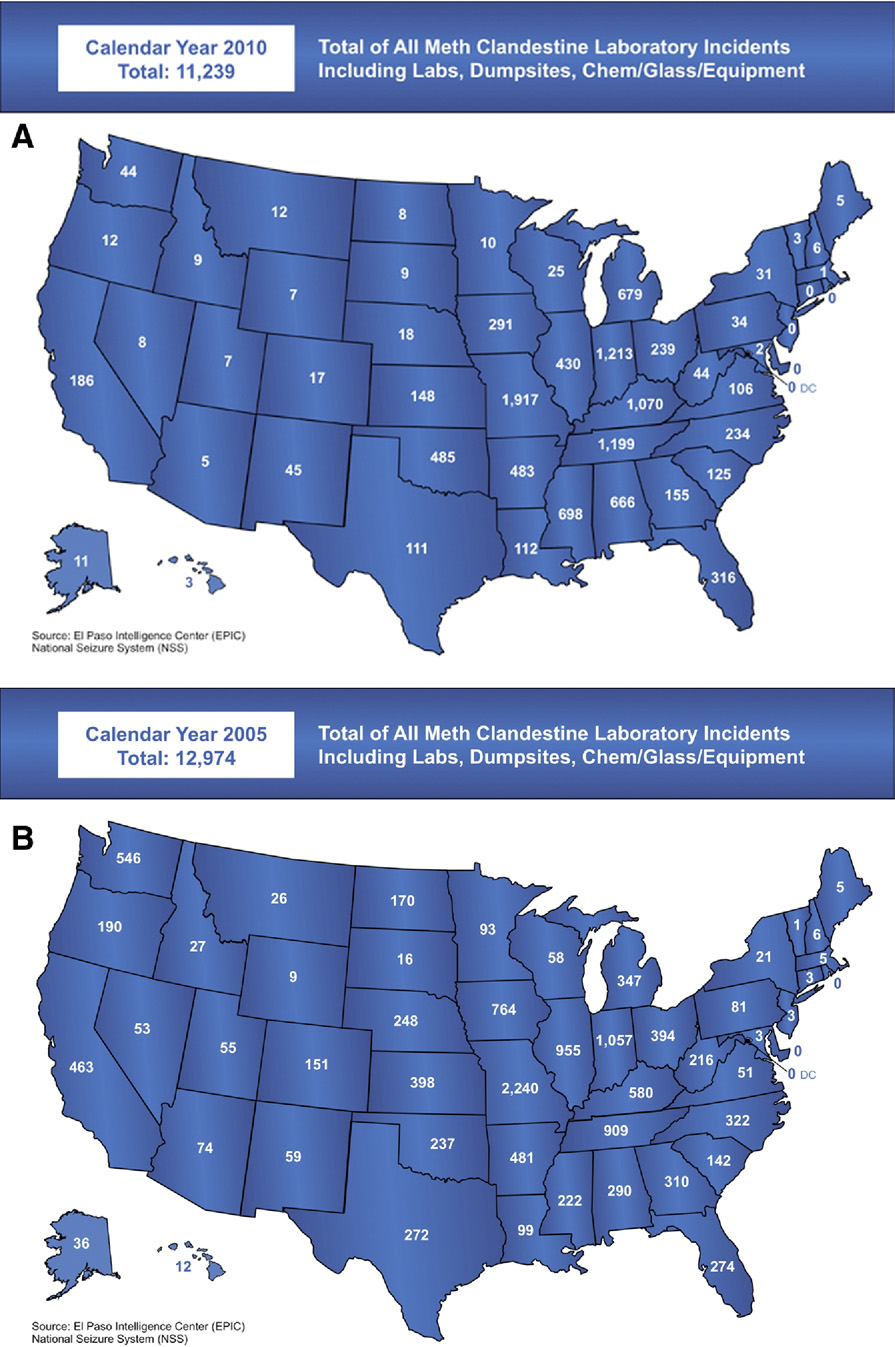

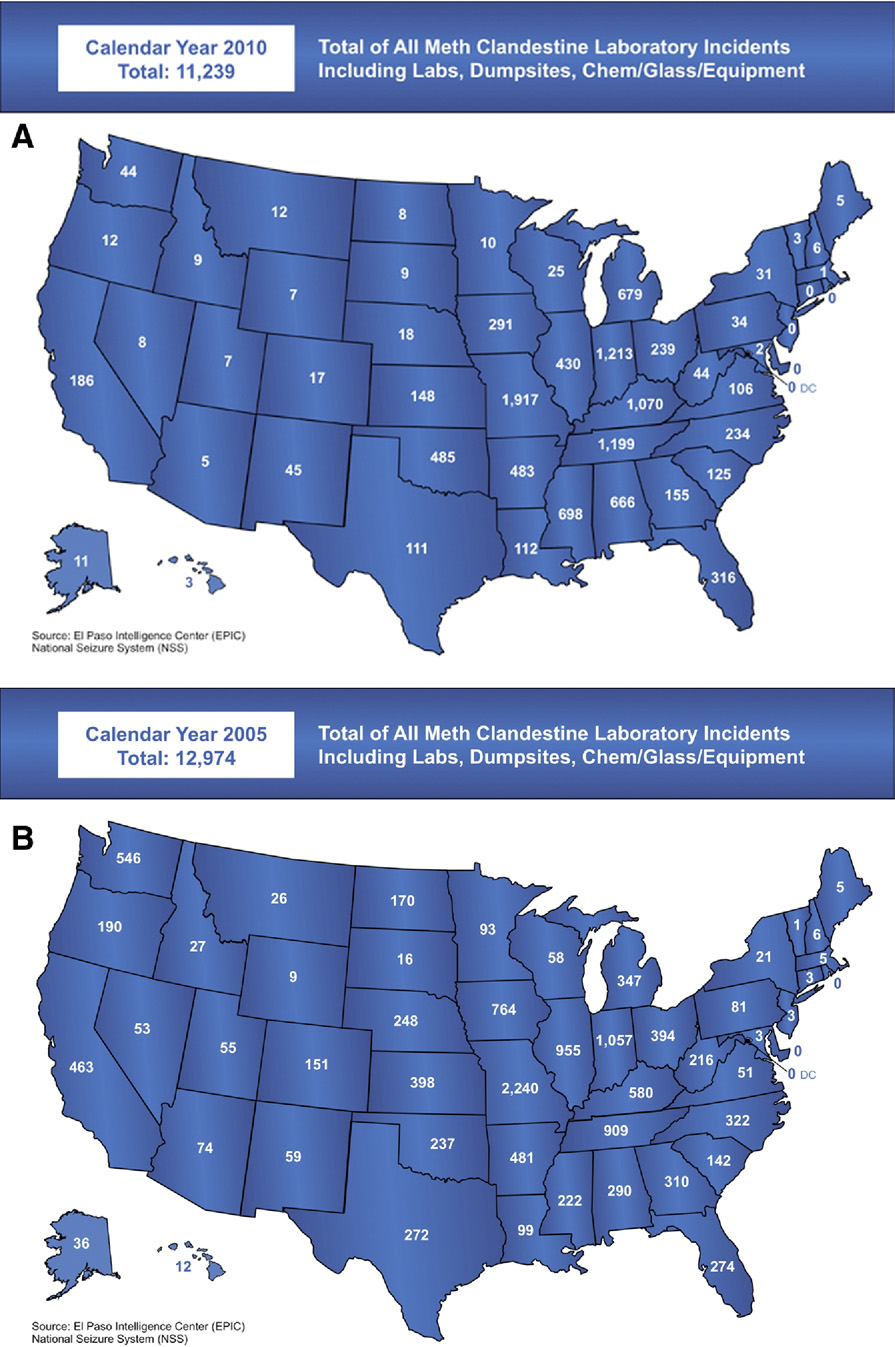

methamphetamine laboratories seized by USA law enforcement agencies

increased by 25% between 2001 and

2004.214 Methamphetamine labora-

tory incidents, defined as discovery of laboratories, dumpsites, or meth-

amphetamine manufacture equipment, also continue to increase. In March

2009, 966 methamphetamine laboratory incidents were reported nation-

ally, an increase from 756 in March 2008 and 596 in March 2007. A total

of 11,239 methamphetamine laboratory incidents were reported nation-

ally in calendar year 2010, with the majority of incidents and the largest

increases occurring in the Midwest and the South

(Fig 4).218,219

Global Trends

International trends show increasing amphetamine use. The 2011

United Nations Office of Drugs and Crime estimates annual prevalence of

amphetamine-type stimulants as the second most widely used illicit drug

in the world, following cannabis. Amphetamines, which include meth-

amphetamine, amphetamine, and methcathinone, are used by 14-56

million people worldwide in 2009, with more specific estimates made

difficult by uncertainty in abuse rates in China and India. Of the

amphetamine-type stimulants, methamphetamine is estimated to be the

most widely manufactured. Asia manufactures a substantial proportion of

the worldwide production of methamphetamine, with methamphetamine

manufacture being particularly prevalent in East and Southeast Asia,

including the Philippines, China, Myanmar, and Malaysia. Global sei-

zures of amphetamine-type stimulants have more than tripled between

1998 and 2009, a much faster rate of increase than has been seen with

seizures of cocaine, heroin, morphine, and cannabis. Methamphetamine

seizures were most common in Oceania, Africa, North America, and

Asia. It is estimated that the majority of methamphetamine laboratories

dismantled worldwide are located in North

America.220

Clandestine Methamphetamine Laboratories

Clandestine methamphetamine laboratories are operated throughout the

USA and make up over 80% of clandestine drug

laboratories.221 In 2008,

DM, February 2012

63

FIG 4.

FIG 4. Trends in meth clandestine laboratory incidents in the USA in (A) 2010 and (B) 2005.

(Source:

http://www.justice.gov/dea/concern/map_lab_seizures.html.) (Color version of fig-

ure is available online.)

64

DM, February 2012

link to page 41 link to page 28 link to page 50 link to page 50 link to page 50 link to page 50 link to page 50 link to page 50 link to page 50 link to page 50

FIG 5.

FIG 5. Illicit meth lab in a bedroom. (Reprinted with permission from Methamphetamine

Awareness and Prevention Project of South Dakota

[http://www.mappsd.org/].) (Color

version of figure is available online.)

6783 methamphetamine laboratories were found, predominantly in the

Midwest.61 Laboratories vary in size from “mom-and-pop” operations to

large-scale “super labs”

(Fig 5).222

Illicit drug manufacturers, also known as “cooks,” may obtain their

“recipes” from other cooks, the chemistry literature, underground culture/

resources, or the

Internet.222 Methamphetamine can be made using

several different techniques, none of which are safe outside the clinical

laboratory. The first method used in the manufacture of illicit metham-

phetamine was developed in the 1960s and involved the precursor

chemical phenyl-2-propanone (P2P). P2P was combined with alcohol and

an aluminum amalgam, usually aluminum foil or wire mixed with a small

amount of mercuric chloride, and allowed to react

overnight.223 The

methamphetamine is then isolated using hydrochloric acid, organic

solvents, and

filters.222

A second method using the precursor chemical P2P combined it with

N-methylformamide and formic acid in the Leuckart reaction; the

intermediate is then refluxed with hydrochloric acid to form methamphet-

amine.222-224 In 1980, the Drug Enforcement Administration made P2P

a Schedule II controlled substance, which led to the illicit manufacture

of

P2P.225 Phenylacetic acid can be combined with acetic anhydride,

lead acetate, or acetic acid with pyridine to form

P2P.222-224 Other

methods of manufacturing P2P involve thorium oxide and pumice or

benzyaldehyde and

nitroethane.222,223 The Chemical Diversion and

DM, February 2012

65

link to page 50 link to page 50 link to page 50 link to page 50 link to page 50 link to page 50 link to page 50 link to page 50 link to page 50 link to page 50 link to page 50 link to page 50 link to page 30 link to page 31

Trafficking Act of 1987 placed restrictions on P2P precursors, forcing

illicit methamphetamine producers to manufacture their own pheny-

lacetic acid. This can be accomplished using benzyl cyanide or

benzylchloride.222

The Drug Enforcement Administration classification of P2P as a

Schedule II controlled substance also led methamphetamine manufac-

turers to seek out new methods by which to produce the

drug.225 In the

early 1980s, methamphetamine manufacturers found that reacting

ephedrine and pyridine with hydrogen iodide and red phosphorus in

carbon disulfide was effective in producing

methamphetamine.223

Ephedrine and pseudoephedrine remain the most popular precursor

chemicals today, because of ease of procurement in common over-

the-counter cold

medicines.222 E sinica can also be used as a source

for ephedrine and

pseudoephedrine.226

Currently, there are 2 methamphetamine-manufacture methods using

ephedrine or pseudoephedrine as a precursor chemical, both with the

common goal of removing a hydroxyl group from the precursor: the

cold or red phosphorus method and the Nazi or Birch method. The

ephedrine or pseudoephedrine is extracted from over-the-counter

medications using water or alcohol and

heat.222 The cold method uses

red phosphorous and hydriodic acid to convert ephedrine/pseu-

doephedrine to

methamphetamine.227 Historically, Freon was used to

extract the finished product, but other organic solvents may be used as

well.222 Hydriodic acid frequently must be illicitly manufactured

because of restrictions placed on it as

well.222 In the Nazi/Birch

method, an alkali metal (typically sodium or lithium) is combined with

anhydrous ammonia and the ephedrine or pseudoephedrine and then

subsequently with water or alcohol and hydrogen chloride gas to form

methamphetamine.222-224 This method is called the Nazi method

because of the widespread belief that it was invented by the Nazis

during World War

II.228

The most recently reported method for making methamphetamine is

called “shake and bake.” The “shake and bake” method requires less

pseudoephedrine, a 2-L soda bottle, and no heat source. The pseu-

doephedrine is crushed and ammonium nitrate is added. This method

can be done anywhere, including in a moving vehicle. A small amount

of methamphetamine is produced using this method, making it useful

for individuals attempting to manufacture their own methamphetamine

but not for larger scale

laboratories.229,230 Tables 3 and

4 list common

chemicals and equipment used in the manufacture of methamphet-

amine.

66

DM, February 2012

link to page 50