Service Delivery Model

Complexity:

Simple

Low complexity

High complexity

Long-term

No ACC intervention

ACC refers to a

ACC is key

maintenance

provider

Coordinator

Services already in

place

Suited to

Medical fees only

Some rehabilitation

Client needs a

•

Long term

these support

Short but necessary

intervention is

range of support:

stable outcome

scenarios:

time off work – will

needed, but no risk

•

Serious Injury

•

Long-term

return to work

flags:

•

difficult to

Home Support

•

quick referral

obtain new job or

within benchmarks

to arrange stay-at-

“flags”

•

Accidental

work

•

rehabilitation

death claims

•

simple

barriers

•

Lump-sum /

alternative job

Independence

placement

allowance

•

Package of

Care

Client contact:

Primary health

Rehabilitation

ACC case manager

• ACC

provider has main

provider

/ coordinator

coordinator, when

client contact - eg.

•

has face- to-

• has face-to-face

required

GPs

face contact

contact

•

No active

•

leads

•

leads

rehabilitation

rehabilitation plan

rehabilitation plan

needed.

development

development

ACC’s core

•

Accept cover

•

Timely service

•

Complex

•

Efficient

role:

•

Pay entitlement

activation

service

payment

efficiently

•

Cost and

coordination·

•

Check in to

decide to invest in

•

Lead

monitor

•

Advise on

plans

rehabilitation plan

secondary

•

Monitor for

development and

prevention

outliers and flags

delivery

•

•

Monitor

Multidisciplinar

providers

y support

Level of risk

No risk and low

•

No significant

•

Risk of high

•

Long term

and liability

liability

risk flags – but …

liability if not

ACC liability – but

for ACC:

•

Fast recovery

intensively managed

this is accepted

reduces ACC

and timely

liability

outcomes not

achieved

Barriers facing long term unemployed, injured, or disabled

workers returning to work.

Report on international literature search

Compiled for ACC by Fiona Knight

16 January 2004

Table of Contents

1

PURPOSE .................................................................................................................................................... 6

BACKGROUND ..................................................................................................................................................... 6

METHOD ............................................................................................................................................................. 7

ORDER OF THE REPORT........................................................................................................................................ 7

2

PART 1: FACTORS IMPACTING ON RETURN TO WORK .............................................................. 8

LENGTH OF TIME OUT OF THE WORK-FORCE ........................................................................................................ 8

THE CONCEPT OF DISABILITY .............................................................................................................................. 8

3

PART 2: BARRIERS AFFECTING RETURN TO WORK ................................................................. 10

A

PERSONAL FACTORS ............................................................................................................................... 10

Attitudinal barriers ...................................................................................................................................... 10

(a)

Personal responses to stressful life events ......................................................................................... 11

(b)

Response to negative experiences ...................................................................................................... 11

(c)

Loss of status ...................................................................................................................................... 12

(d)

Lack of confidence ............................................................................................................................. 12

(e)

Apprehension regarding re-employment ............................................................................................ 12

PERSONAL ABILITIES ......................................................................................................................................... 13

(a) Capacity to change. .............................................................................................................................. 13

(b)

Personal expectations ........................................................................................................................ 14

(c)

Education ........................................................................................................................................... 14

EMPLOYABILITY ............................................................................................................................................... 16

HEALTH FACTORS ............................................................................................................................................. 17

(a)

Pain management ............................................................................................................................... 17

(b)

Use of cigarettes, drugs, and alcohol ................................................................................................. 18

(c) Mental health ........................................................................................................................................ 19

REFUSAL TO ACCEPT JOBS ................................................................................................................................. 20

AGE, GENDER, ETHNICITY ................................................................................................................................. 20

(a) Age ........................................................................................................................................................ 20

(b)

Gender ............................................................................................................................................... 22

(c)

ethnicity .............................................................................................................................................. 22

TYPE OF DISABILITY / INJURY ............................................................................................................................ 24

PRE-INJURY CIRCUMSTANCES ........................................................................................................................... 25

(a)

Family circumstances ........................................................................................................................ 25

(b)

Job satisfaction .................................................................................................................................. 26

(c)

Job history .......................................................................................................................................... 27

(d) criminal record .................................................................................................................................... 27

(e) obesity ................................................................................................................................................... 27

B

EXTERNAL FACTORS ................................................................................................................................ 27

PERCEPTION OF EMPLOYERS / LACK OF KNOWLEDGE ........................................................................................ 27

JOB ADAPTATIONS ............................................................................................................................................. 29

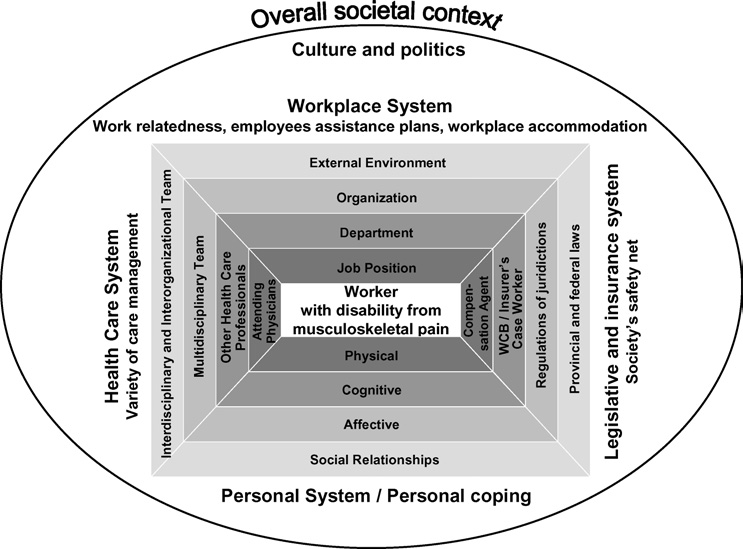

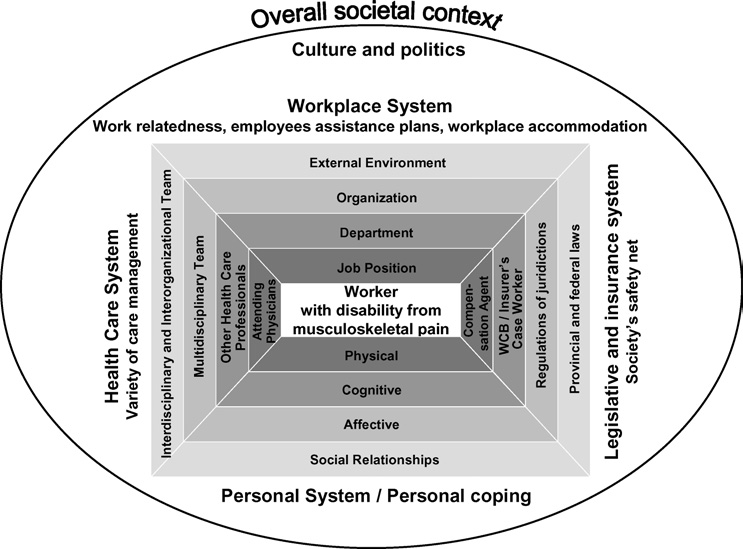

CASE MANAGEMENT/ REHABILITATION ISSUES ................................................................................................. 30

(a)

Behavioural dimension ...................................................................................................................... 30

(b)

Cognitive dimension ........................................................................................................................... 30

(c)

The affective dimension ...................................................................................................................... 31

(c)

Environmental .................................................................................................................................... 31

LAWYERS’/ ADVOCATES’ ATTITUDES ................................................................................................................ 31

FOCUS ON DISABILITY (RATHER THAN ABILITY) ................................................................................................ 32

CO-WORKER ATTITUDES ................................................................................................................................... 32

TRANSPORT ISSUES ........................................................................................................................................... 33

RETAINING EMPLOYMENT ................................................................................................................................. 33

SELF-EMPLOYMENT .......................................................................................................................................... 35

Page 2 of 144

LABOUR MARKET CONDITIONS .......................................................................................................................... 35

COMPENSATION ENTITLEMENT ......................................................................................................................... 36

CONCLUDING REMARKS .................................................................................................................................... 37

4

PART 3: PROGRAMMES AND INITIATIVES TO REMOVE BARRIERS ..................................... 39

ADDRESSING LENGTH OF TIME OUT OF THE WORK FORCE ................................................................................. 39

(a)

Unemployed ....................................................................................................................................... 39

(b)

Disabled / injured workers ................................................................................................................. 39

ADDRESSING THE CONCEPT OF DISABILITY ....................................................................................................... 40

ADDRESSING PERSONAL ISSUES ........................................................................................................................ 41

(a)

Personal responses to stressful life events ......................................................................................... 41

(b)

Response to negative experiences ...................................................................................................... 41

(c)

Loss of status ..................................................................................................................................... 42

(d)

Lack of confidence ............................................................................................................................. 43

(e)

Apprehensions regarding re-employment .......................................................................................... 44

PERSONAL ABILITIES AND ATTRIBUTES ............................................................................................................. 45

(a)

capacity to change ............................................................................................................................. 45

(B)

PERSONAL EXPECTATIONS ....................................................................................................................... 46

(c)

Education ........................................................................................................................................... 47

(d)

Ability to speak the local language .................................................................................................... 48

EMPLOYABILITY ............................................................................................................................................... 49

ADDRESSING HEALTH FACTORS ........................................................................................................................ 51

(a)

Pain management ............................................................................................................................... 51

(B)

USE OF CIGARETTES, DRUGS AND ALCOHOL ............................................................................................ 53

(c)

Mental health ..................................................................................................................................... 53

(d)

Evidence-based Return to Work Guidelines ....................................................................................... 54

REFUSAL TO ACCEPT JOBS ................................................................................................................................. 54

AGE, GENDER, ETHNICITY ................................................................................................................................. 56

(a)

Age ..................................................................................................................................................... 56

(b)

Gender ............................................................................................................................................... 59

(c)

Ethnicity ............................................................................................................................................. 61

TYPE OF DISABILITY .......................................................................................................................................... 62

(a)

Mental health problems ..................................................................................................................... 62

(b)

People with traumatic brain injury (TBI) .......................................................................................... 64

(c)

People with hearing problems ........................................................................................................... 65

(d)

People with sight problems ................................................................................................................ 65

(e)

People with back problems ................................................................................................................ 66

(f)

People with serious injuries ............................................................................................................... 67

(g)

People with spinal injuries ................................................................................................................. 67

(h)

Other injuries / disabilities ................................................................................................................ 68

PROBLEMS ARISING FROM PRE-INJURY CIRCUMSTANCES .................................................................................. 68

(a) Family circumstances ........................................................................................................................ 68

(b)

Job satisfaction .................................................................................................................................. 68

(c)

Job history .......................................................................................................................................... 68

(d)

Relocation .......................................................................................................................................... 69

(e)

Criminal records ................................................................................................................................ 70

(f)

Obesity ............................................................................................................................................... 70

ATTITUDES OF EMPLOYERS ............................................................................................................................... 71

(a)

The Disability symbol ........................................................................................................................ 71

(b)

Duration of unemployment ................................................................................................................. 72

(c)

Educating employers regarding disabilities ...................................................................................... 73

(d)

Understanding return to work programmes ....................................................................................... 73

JOB ADAPTATIONS ............................................................................................................................................. 74

(a)

Supported employment ....................................................................................................................... 74

(b)

Assistive technology ........................................................................................................................... 76

(c)

Modification of job duties .................................................................................................................. 76

(d)

Teleworking ....................................................................................................................................... 77

(e)

Work trials ......................................................................................................................................... 79

Page 3 of 144

CASE MANAGEMENT / REHABILITATION ISSUES ................................................................................................. 79

ADDRESSING LAWYER AND ADVOCATE ATTITUDES .......................................................................................... 82

FOCUS ON ABILITY RATHER THAN DISABILITY .................................................................................................. 84

ADDRESSING CO-WORKER ATTITUDES .............................................................................................................. 84

ADDRESSING TRANSPORT ISSUES ...................................................................................................................... 85

RETAINING EMPLOYMENT ................................................................................................................................. 86

(a)

Earnings supplements / financial assistance to employees ................................................................ 87

(b)

Wage subsidies for employees ............................................................................................................ 87

(c)

Retention incentives for employers and /or employees ...................................................................... 87

(d)

On-job support ................................................................................................................................... 88

(e)

Protection of employment .................................................................................................................. 89

(f)

Quota systems .................................................................................................................................... 89

(g)

Levy systems ....................................................................................................................................... 90

SELF-EMPLOYMENT .......................................................................................................................................... 90

Operating within prevailing labour market conditions ............................................................................... 93

MULTI-TARGETED PROGRAMMES ..................................................................................................................... 95

RESULTS BASED FUNDING ................................................................................................................................. 96

CONCLUDING REMARKS .................................................................................................................................... 97

5

PART 4: BEST PRACTICE ................................................................................................................... 100

EVALUATION OF PROGRAMMES ....................................................................................................................... 101

PRINCIPLES OF GOOD INTERVENTION DESIGN .................................................................................................. 102

1 Recruitment of participants is the start of the intervention ................................................................... 102

2 View intervention as a social influence ................................................................................................. 102

3 Target motivation, skills, knowledge and resources for coping ............................................................ 103

4 Build self-sufficiency ............................................................................................................................. 103

5 To be successful requires the confidence to try to succeed.................................................................... 103

6 Allow for individual differences............................................................................................................. 103

7 Use active teaching and learning methods, rather than didactic techniques ........................................ 103

8 Blend active learning with model demonstration, graduated utilisation of skills and positive feedback

................................................................................................................................................................... 103

9 Inoculate against setbacks ..................................................................................................................... 104

PREDICTING WHO MIGHT BECOME LONG TERM UNEMPLOYED ......................................................................... 104

MODIFIED WORK DUTIES ................................................................................................................................. 106

DEMAND-SIDE JOB DEVELOPMENT .................................................................................................................. 106

MAINTAINING EMPLOYMENT .......................................................................................................................... 107

BUSINESS PARTNERSHIP .................................................................................................................................. 108

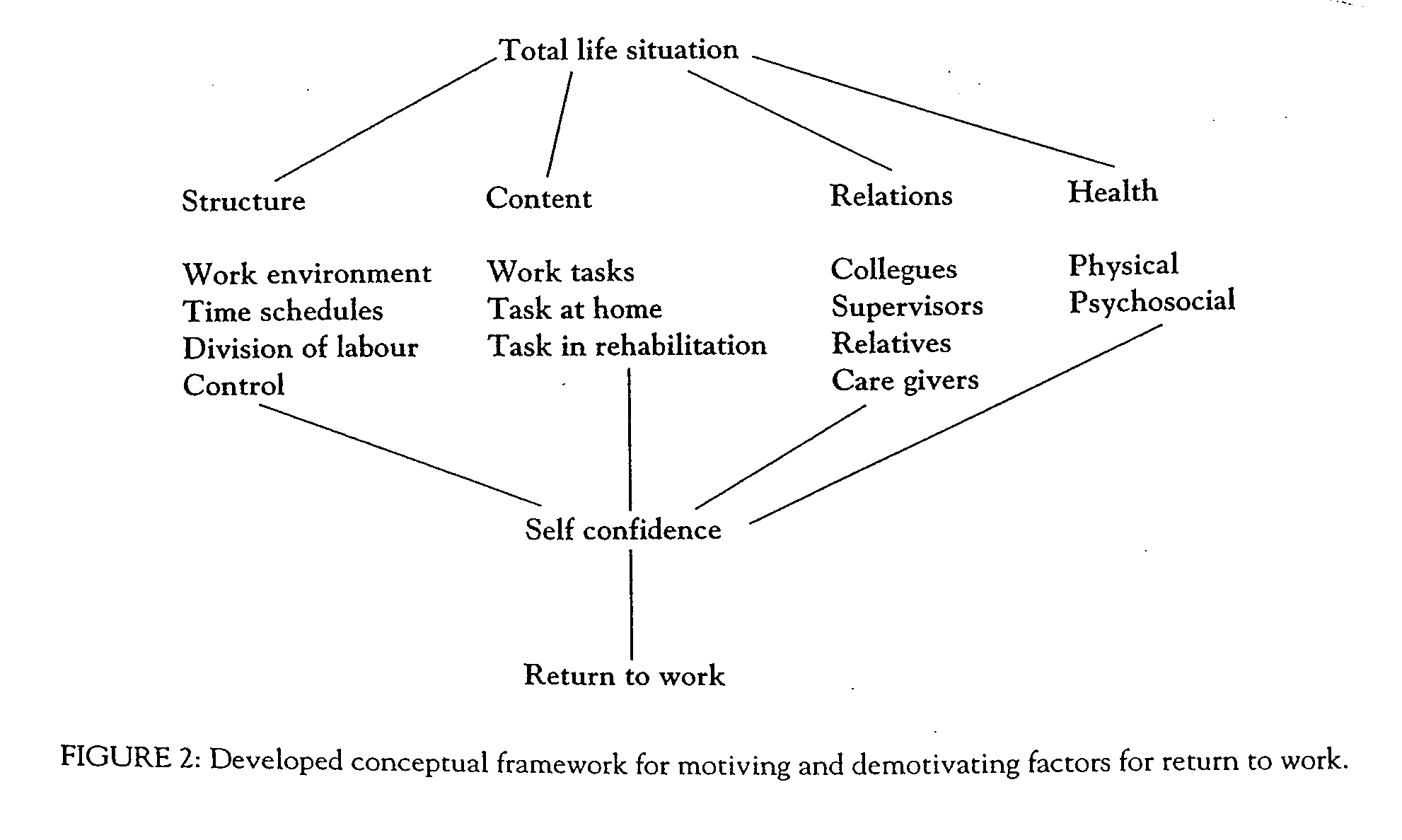

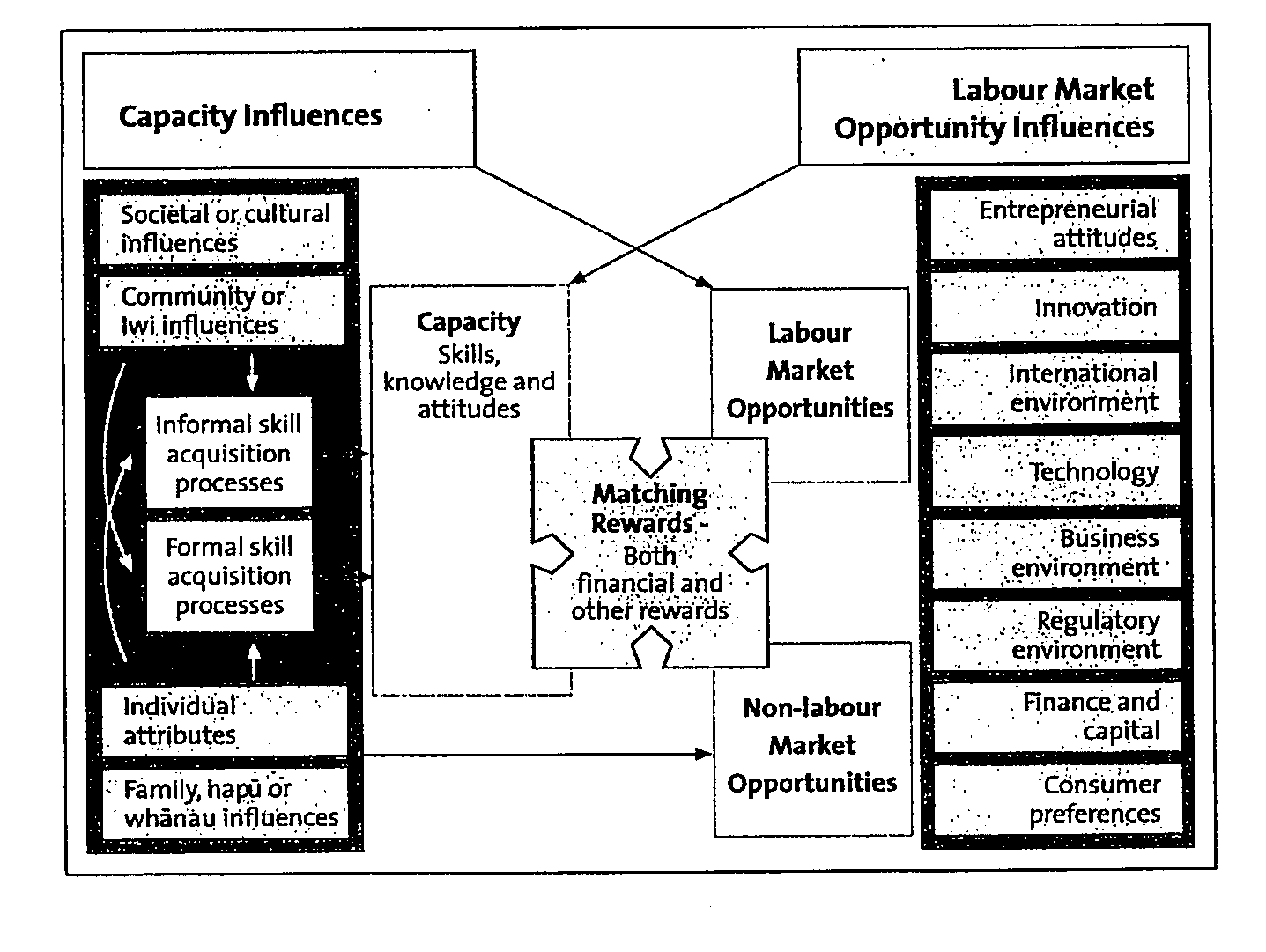

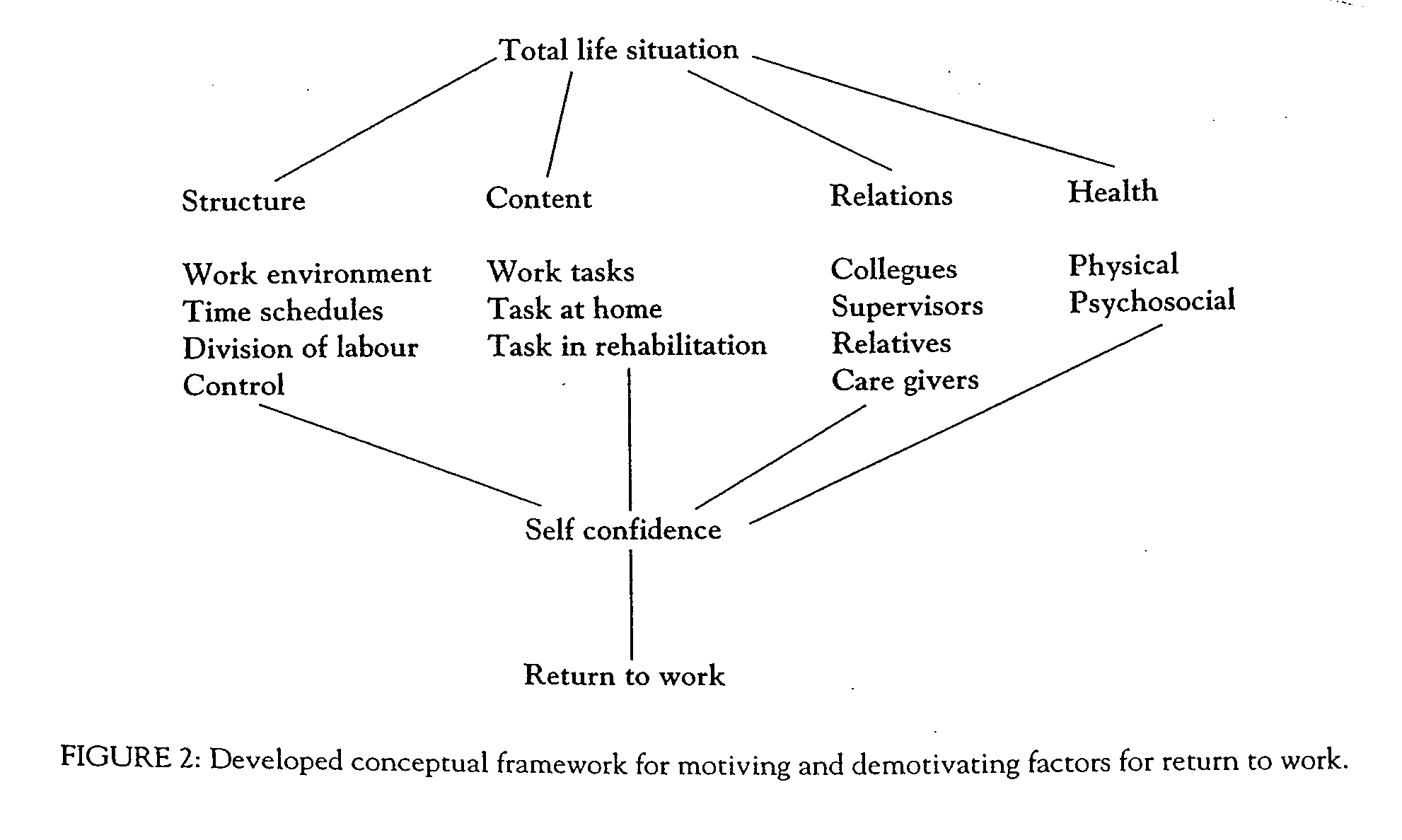

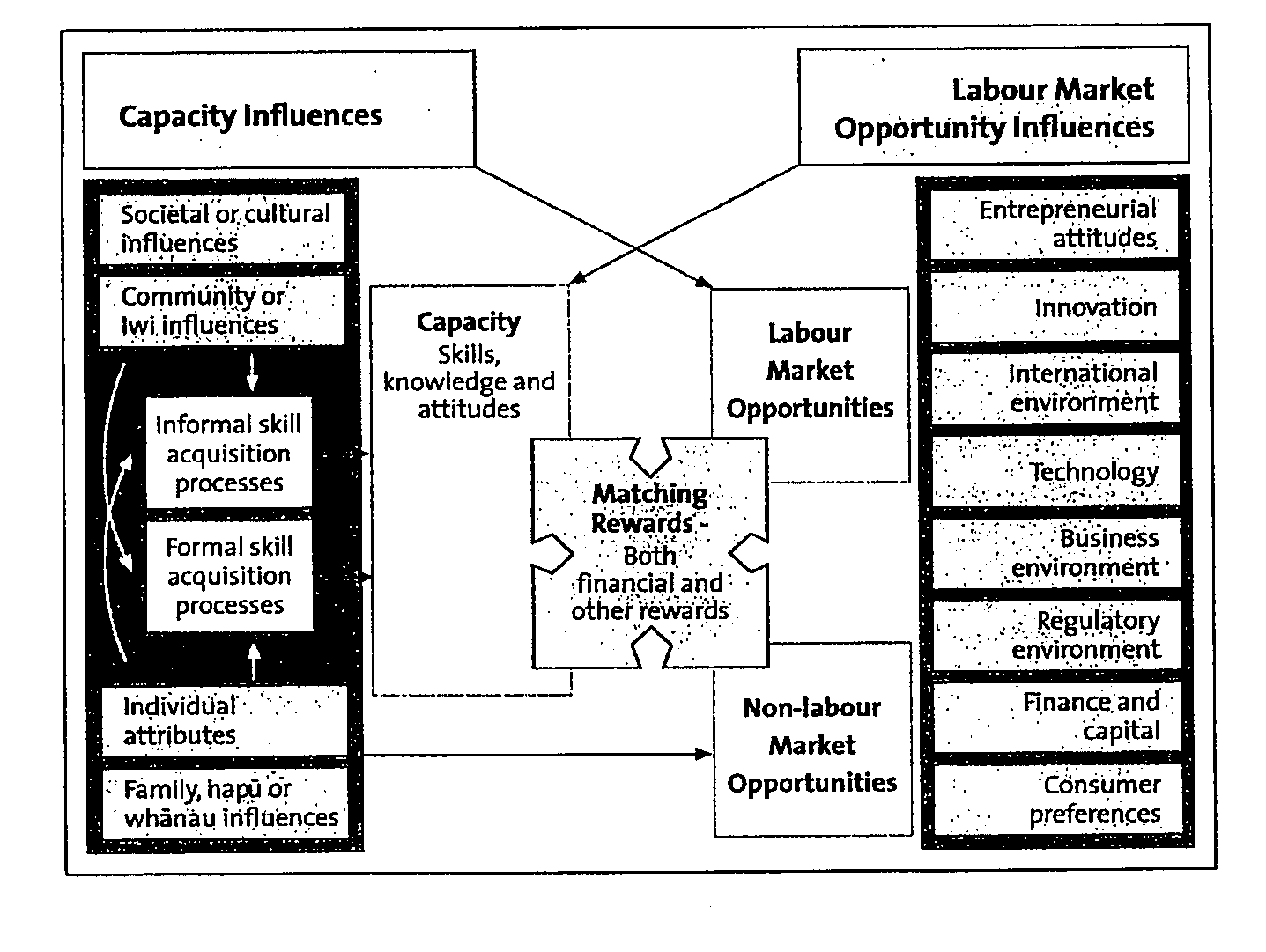

HUMAN CAPABILITY FRAMEWORK ................................................................................................................. 110

THE CURRENT NEW ZEALAND LABOUR MARKET ............................................................................................ 112

HELPING LONG TERM CLAIMANTS ................................................................................................................... 113

HELPING NEWLY INJURED ............................................................................................................................... 113

CASE MANAGEMENT ....................................................................................................................................... 114

POLICY DEVELOPMENT ................................................................................................................................... 115

APPENDICES ................................................................................................................................................... 117

APPENDIX ONE: HOW TO RELATE TO PEOPLE WITH DISABILITIES ............................................................... 117

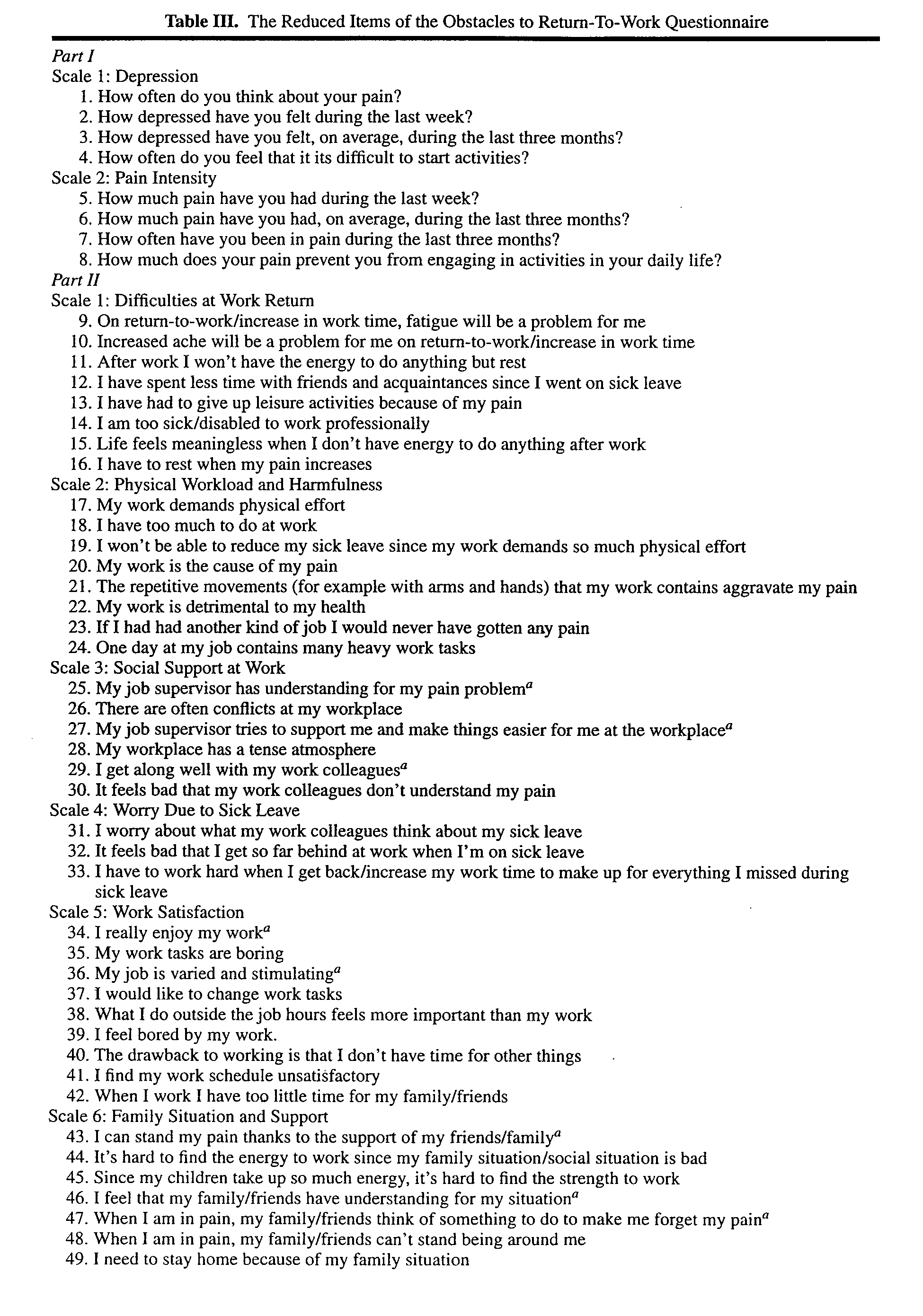

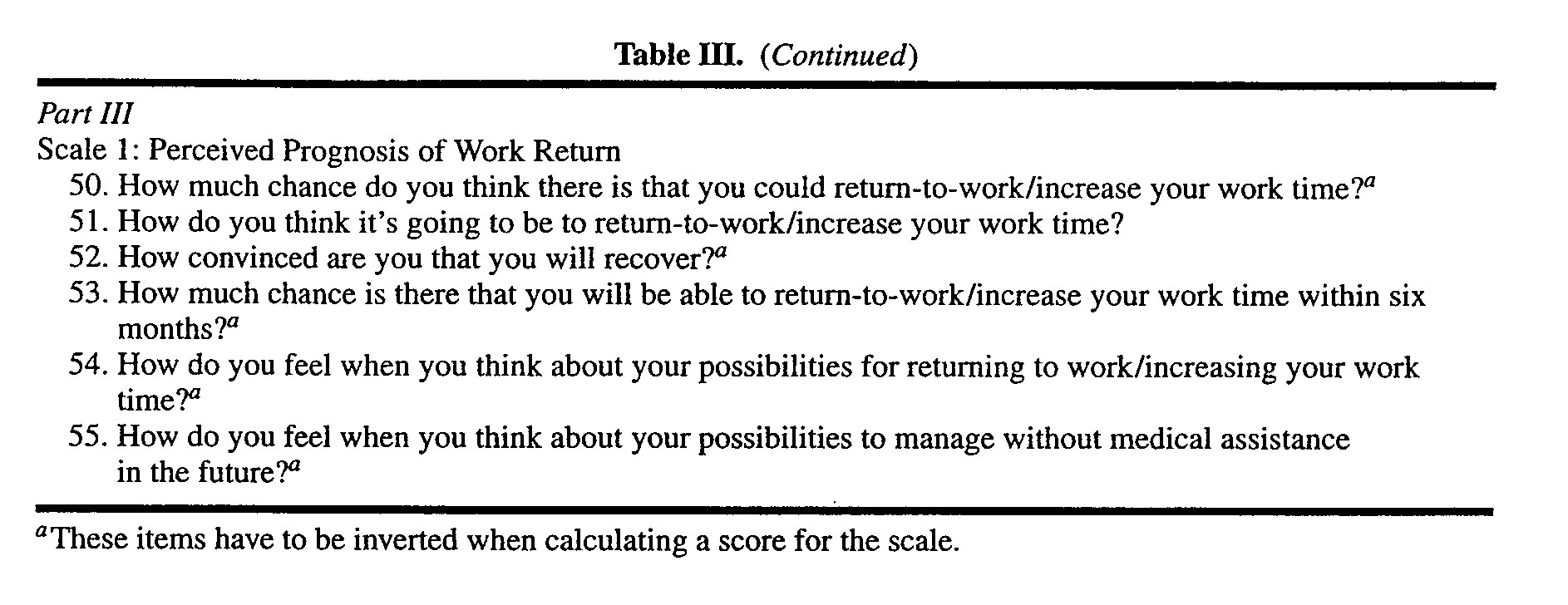

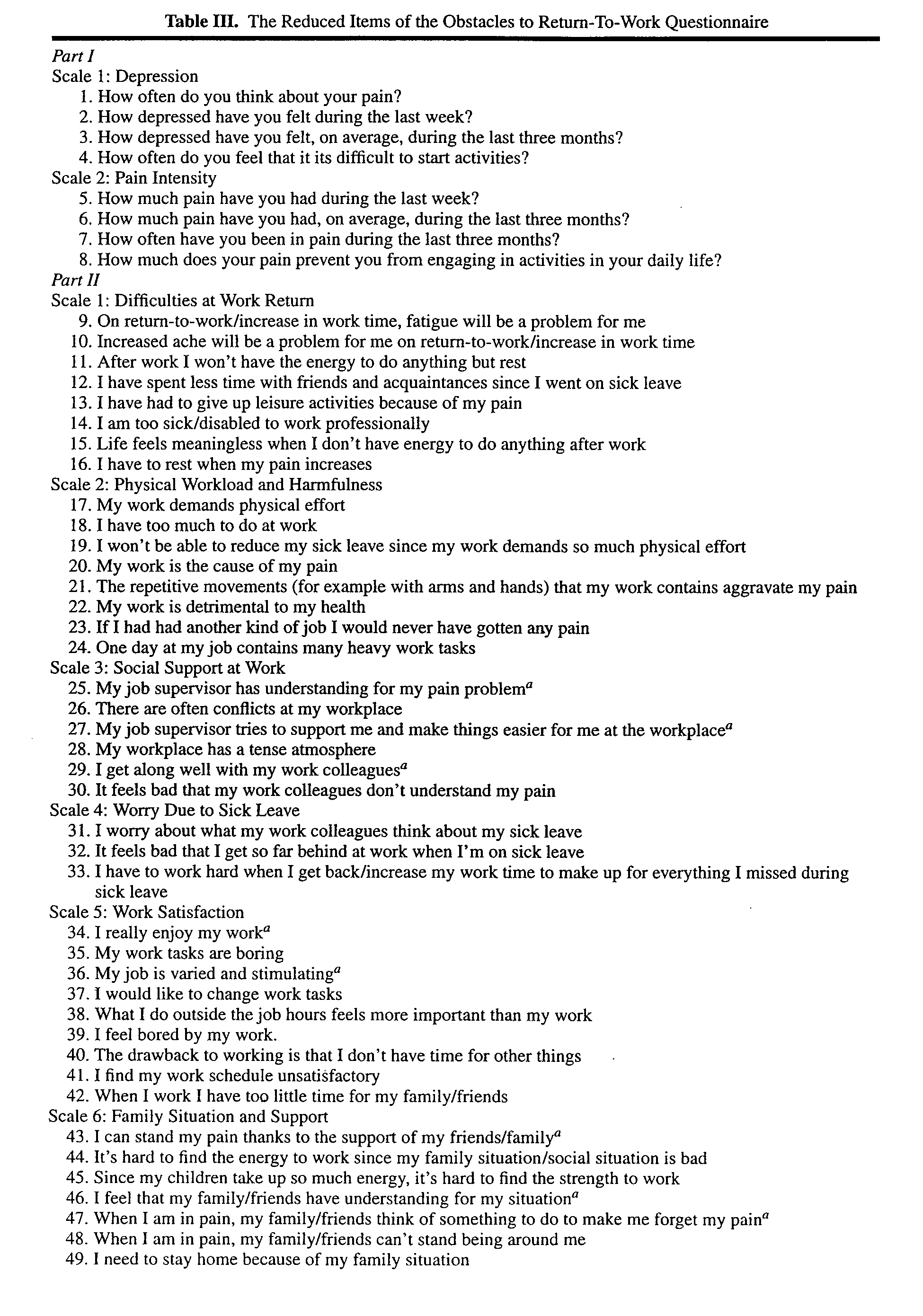

APPENDIX TWO: OBSTACLES TO RETURN TO WORK QUESTIONNAIRE......................................................... 122

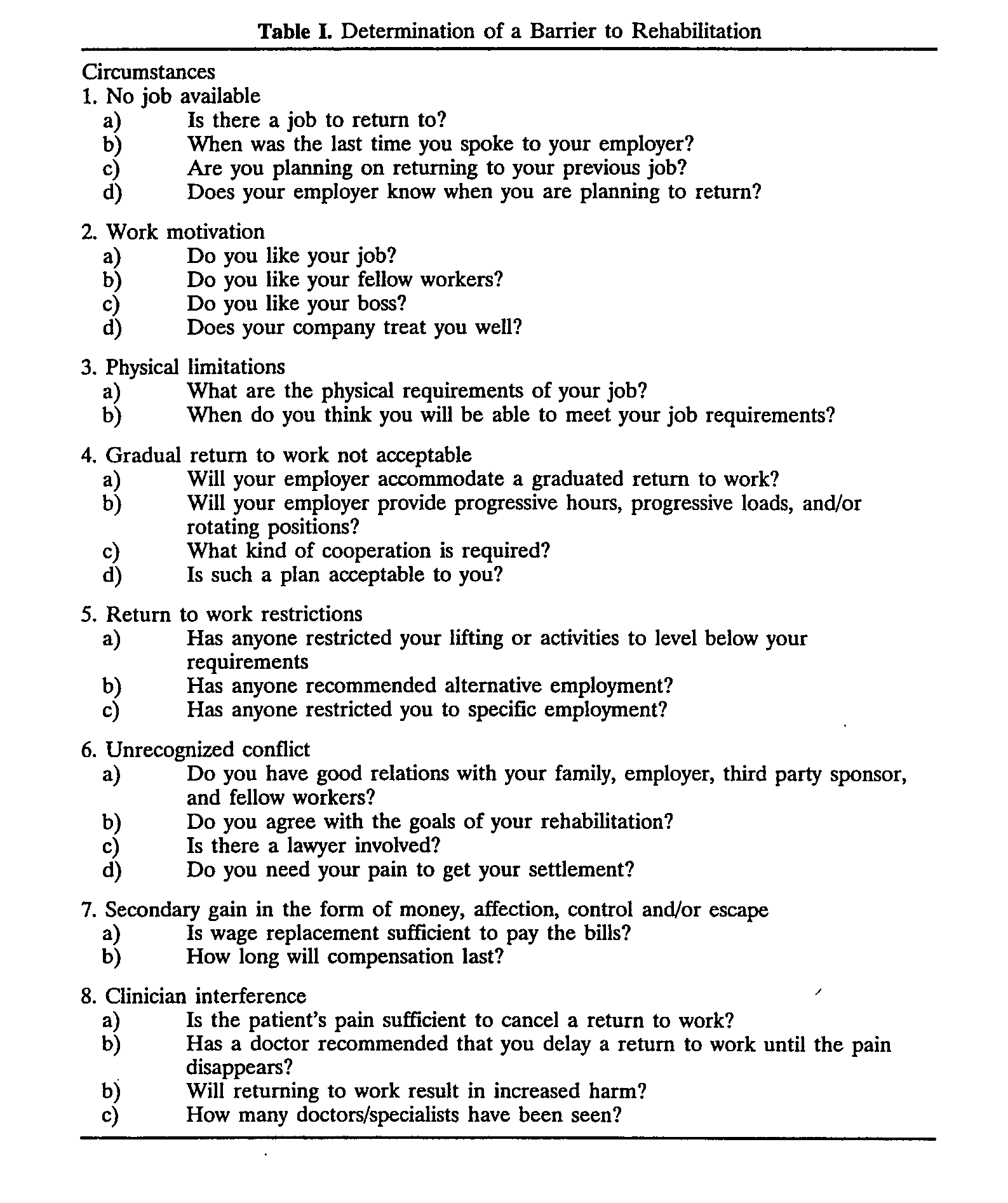

APPENDIX THREE: IDENTIFYING BARRIERS TO REHABILITATION .............................................................. 124

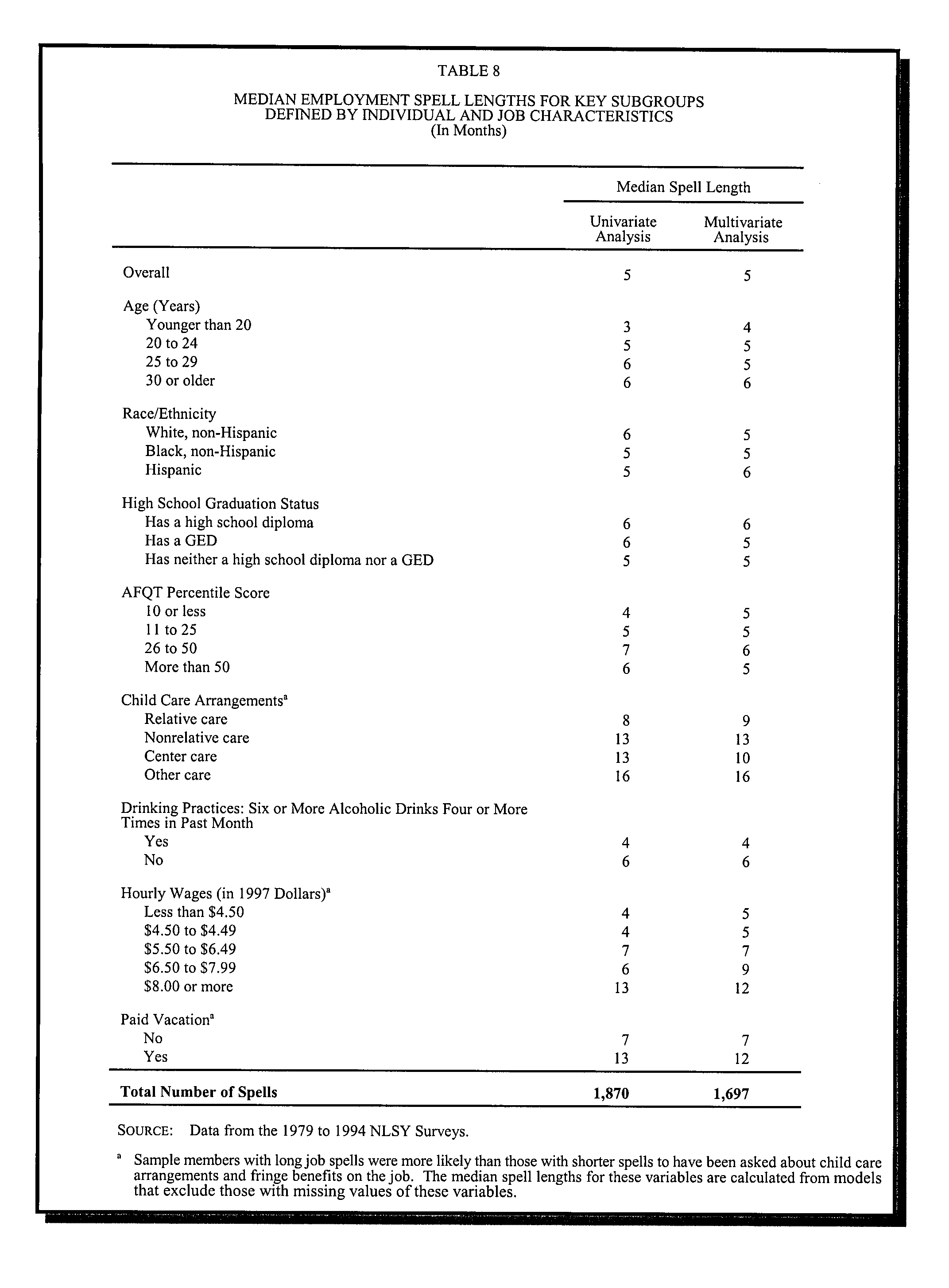

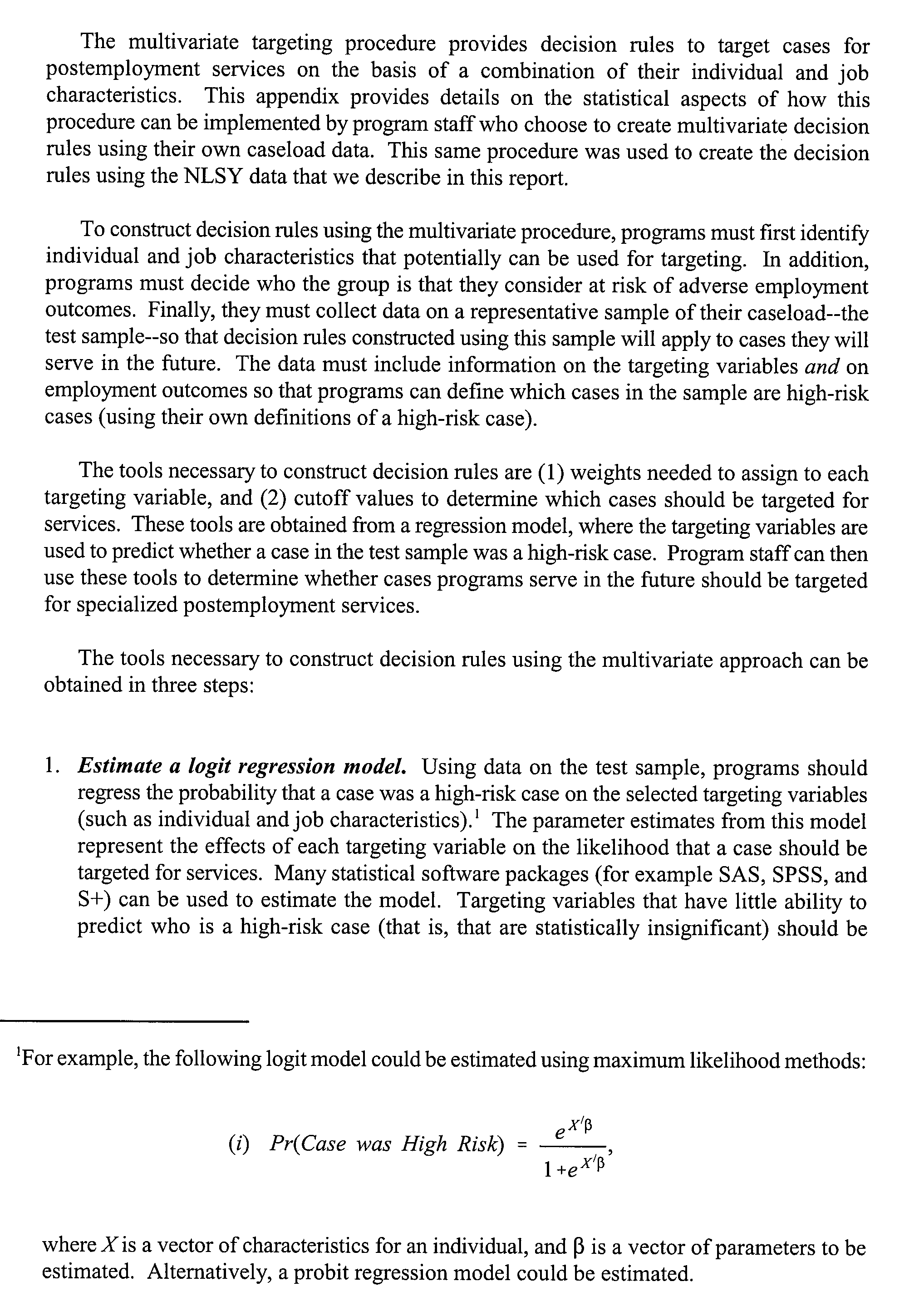

APPENDIX FOUR: IDENTIFYING PEOPLE NEEDING ASSISTANCE WITH JOB RETENTION ................................ 124

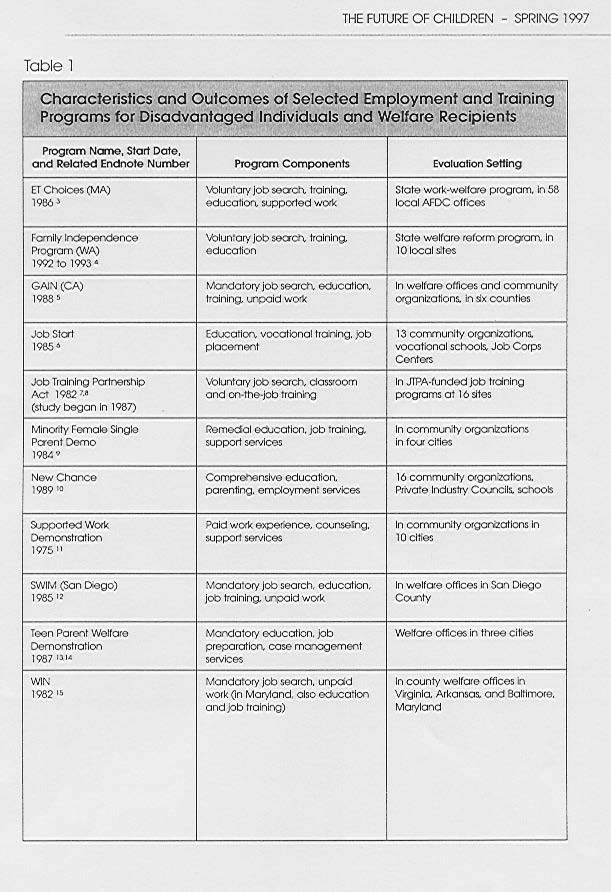

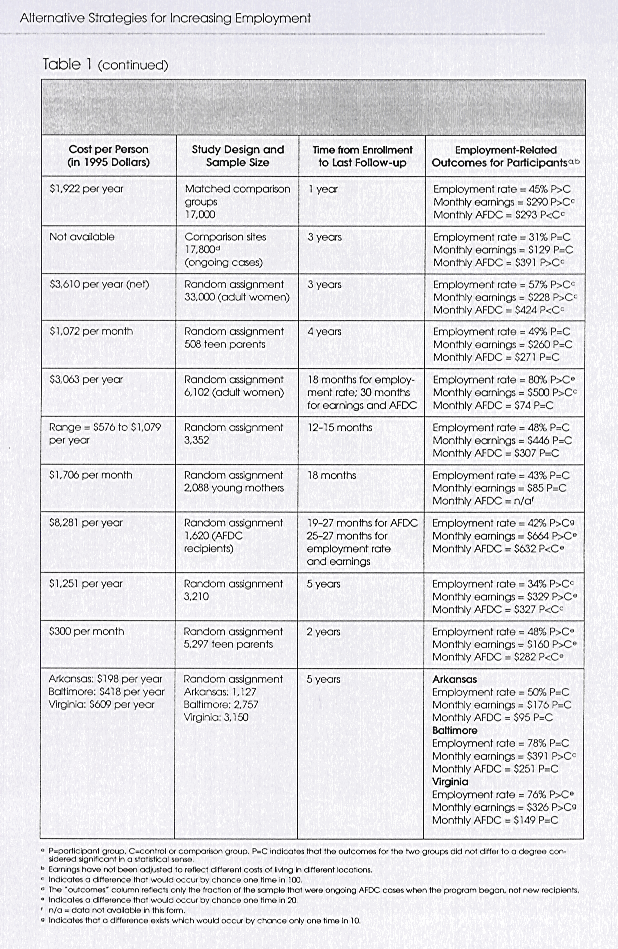

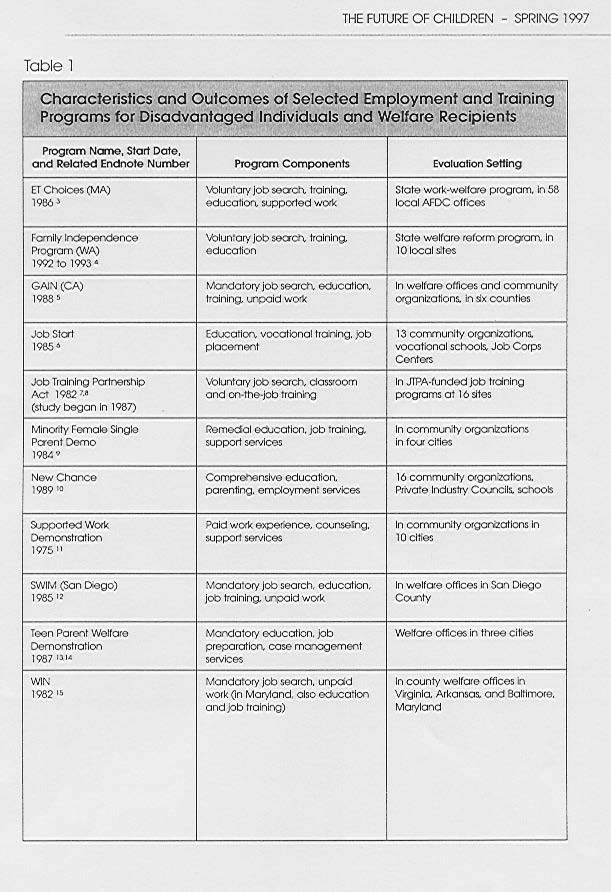

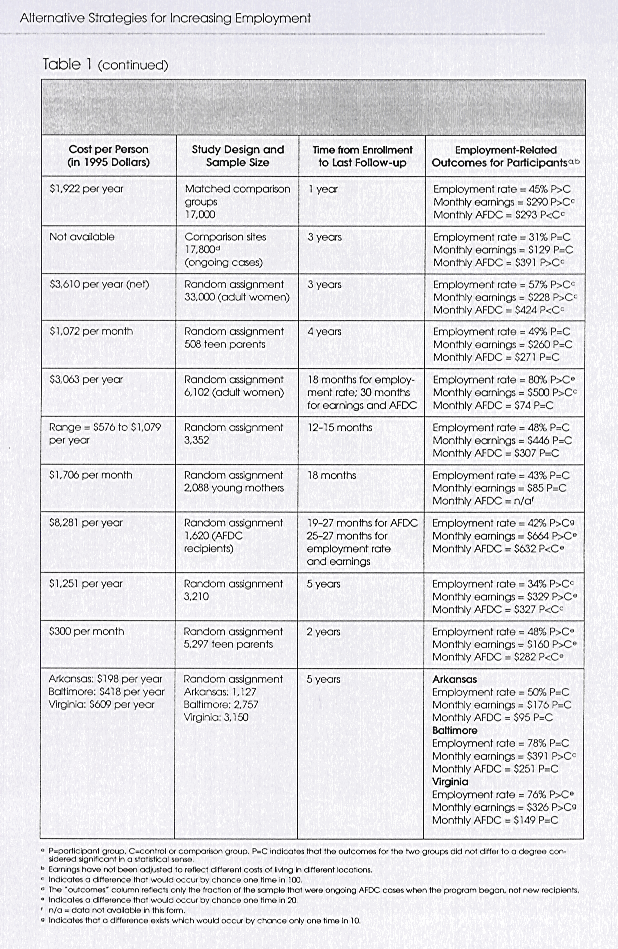

APPENDIX FIVE: EVALUATION OF SELECTED EMPLOYMENT AND TRAINING PROGRAMMES ........................ 129

BIBLIOGRAPHY ............................................................................................................................................... 131

Page 4 of 144

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank several ACC staff for their assistance in the development of this

project:

• Helen Brodie and her staff in Information Services, who inter-loaned much of the

resource material for me;

• Ezrai Fae, Laura Ager, Denise Udy, Raewyn Cole, Raj Krishnan and Caro Henckels

who provided valuable comments on the draft report, and suggestions for

incorporation in the report; and

• Donna Engel, who assisted with the production of the report.

Disclaimer

Any errors and omissions in the report are mine. Those views and opinions stated but not

sourced are mine, and do not necessarily reflect those of ACC.

Page 5 of 144

link to page 7 link to page 7

Introduction

1

Purpose

1.1

The purpose of this report is to:

•

Identify the barriers affecting return to work for people who have been out

of work for long periods, whether due to injury or unemployment, based on

an appraisal of international research and interventions;

•

Summarise programmes and initiatives which address these barriers; and

•

Recommend initiatives to remove these barriers for ACC long term

claimants.

Background

1.2

There are currently about 14,000 long term claimants with ACC. While there has

been a significant reduction in the numbers of long term claimants over the last few

years, recently there has been a decline in the rate of reduction. This partly reflects

the impact of the Injury Prevention, Rehabilitation, and Compensation Act 2001,

which required additional assessment of long term claimants before they could

return to independence.

1.3

Other factors affecting the numbers of long term claimants include:

•

As a result of advances in road safety, technology, drug development and

rehabilitation techniques, more people are surviving what would previously

have been fatal accidents, but they sustain serious injuries which take longer

times to heal.

1

•

People injured at a young age still have significant life expectancies. Young

adult males, with such long life expectancies, are a particularly high risk

group in sustaining severe injuries, although research indicates that in

general younger age at injury is associated with good recovery.

1.4

This project was commissioned in the expectation that many of the problems faced

by these long term claimants are similar to those facing long term unemployed,

such as lack of work skills and attitudes, low self-esteem, poor employability, and

negative perceptions and expectations of employers. Researchers have recently

established a relationship between depression and welfare reliance, although

insufficient work has yet been done to quantify this relationship.

2

1.5

This project aims to identify the barriers hindering return to work, and to

investigate overseas practices that deal with them, with a view to identifying

appropriate programmes for use in New Zealand. Such programmes, if successful,

could be expected to enhance significantly the lives of long term claimants.

1 Yasuda et al: 2001 p 853

2 Kalil et al, August 1998 p 12

Page 6 of 144

link to page 8

1.6

Research into individuals with spinal cord injuries indicated that those who were

employed post-injury reported more satisfaction with their lives, required fewer

medical treatments, and rated their overall adjustment higher than individuals who

were not employed

3. There is abundant similar evidence to support making efforts

to help injured workers regain and retain employment. This literature search is

designed to identify ways in which ACC can help its long-term claimants gain

similar life satisfaction.

Method

1.7

The literature search focused on Internet resources and inter-loans sourced through

ACC’s Information Services team. Initial key words included

(long-term)

unemployment, re-employment, barriers, return to work, disabled workers,

unemployable, and

work-ready. Subsequent internet research focused on the actual

barriers identified, and how to address these.

1.8

A consistent pattern emerged in the barriers identified, supporting the original

premise that similar problems face the long term unemployed and those out of

work for long periods due to injury.

1.9

Two significant factors which impact on return to work were identified:

a) Length of time out of the workforce, and

b) The concept of disability.

1.10 While these are closely inter-related, and provide the focus for this report, each

factor is first discussed separately.

1.11 The barriers identified have been addressed simply as barriers against return to

work, regardless of whether it was identified as a barrier to a long term unemployed

/ disabled / injured person. For many barriers, they are the same barriers facing

the long term unemployed , disabled people, and injured people.

A full bibliography of source material is included.

Order of the report

The report is in five main sections:

i)

An introductory section identifying general factors impacting on return to

work after a period out of the work-force;

ii)

The barriers affecting return to work;

iii)

A description of appropriate programmes used overseas to overcome

barriers affecting return to work;

iv)

Analysis of different initiatives and a summary of best practice

v)

recommendations for ACC to assist long term claimants return to work.

3 Yasuda, et al 2002 Article summary

Page 7 of 144

link to page 9 link to page 9 link to page 9 link to page 9 link to page 9 link to page 9 link to page 9

2

Part 1: Factors impacting on return to work

Length of time out of the work-force

2.1

International research concludes that the longer a person is out of work and

receiving some form of benefit or compensation payments, the less chance they

have of returning to full time work. The motivation to find work deteriorates over

time

4. According to Regan and Stanley of the UK Institute of Public Policy

Research, (IPPR) “once a person has been on the benefit for 12 months, the average

duration of their claim will be eight years, with only a one in five chance of

returning to work within five years”.

5 There is considerable evidence that the

longer people remain in receipt of financial assistance, either their mental and

physical health is likely to decline, or they enjoy their changed lifestyle which does

not incorporate being at work.

2.2

An orthopaedic physician’s study of over 100 injured workers found that those who

lost no workdays, or returned to work within 15 workdays of sustaining the injury

were still in employment two years later.

6

2.3

There are other reported risks when an injured worker is out of work for a long

time. For example, in America, because lost time has become routine and

expected even for relatively minor injuries, the Texas Workers Compensation

Commission cautions employers to the likelihood of malingering or of fraudulent

claims.

7

2.4

Notwithstanding these concerns, most people who claim financial assistance

following injury or illness expect to return to work.

8 Up to 40% of such people do

not see their health problems as an obstacle to finding work, but cite a wide range

of other obstacles instead. Each of these obstacles is investigated below.

2.5

An ACC survey of exited claimants showed that about half those not working

considered it was due to their health. Other reasons included age (and ensuing

retirement), family circumstances, employer reluctance to hire people with back

injuries, pregnancy, redundancy, and the lack of suitable / available jobs.

9

The concept of disability

2.6

There is a complex relationship between disability, poverty, low skills and

worklessness. The IPPR found that people who become disabled are more likely to

have been at an economic disadvantage before they became disabled.

10 They are

then more likely to move into low paid, low status jobs, to be in manual

occupations, and to have lower average hourly earnings than their non-disabled

peers, even taking into account age, education, and occupation. The chance of

becoming unemployed again is higher: 33% for people with disabilities compared

4 NZ Employment Service 1996

5 Regan and Stanley: 2003 p 58

6 Melhorn 1996 pp18-30

7 Texas Workers’ Compensation Commission website: <www.twcc.state.tx.us/commission/divisions/rtw>

8 Pathways to Work 2002 p 11

9 BRC January 2003 Appendix 3 Table 4

10 Regan and Stanley 2003 p 57

Page 8 of 144

link to page 10 link to page 10 link to page 10 link to page 10

with 20% for those without disabilities, despite evidence

11 that people with

disabilities have a better attendance record, stay longer in a job and have fewer

accidents in the workplace than the non-disabled.

2.7

In economic terms, as a disability reduces a worker’s productivity, it also weakens

their relative value on the labour market, and power to compete with other job-

seekers.

12 What may be a temporary impairment more easily converts to chronic

disability and dependence when there is a surplus of skills, and as a consequence,

unemployment and disability are overlapping contingencies. If someone with a

temporary impairment cannot find a suitable job, it is likely that the labour market

conditions will interact with their health condition to produce chronic disability.

Whether the resulting unemployability is due to unemployment or disability is then

hard to distinguish.

2.8

Behavioural elements are significant determinants of chronic disability

13. These

include:

•

The recognition of symptoms of impairments;

•

The perception of their incapacitating effects; and

•

The choice of coping strategy.

2.9

The first step on the road to disability is the recognition of the symptoms of an

impairment by the person and/or significant others. The impaired worker will then

try to adapt their condition in a way that is socially acceptable and in agreement

with their own preferences. Workers will define themselves as disabled if they

perceive themselves being impaired beyond remedy, and if they experience a

substantial reduction in work performance. They will be more inclined to do so if

the financial and psychological consequences of disability are not severe.

2.10 The response to injury can be either positive or negative: vocational rehabilitation

and return to work, or chronic disability and persistent dependency. The form of

response will be influenced by the reactions of external parties including

employers, family and household members, case managers, and health

professionals.

2.11 In choosing their response, an injured person will weigh the psychological and

pecuniary benefits and risks. Returning to work brings a person the stress of

employment, having to cope with the vagaries of the labour market and assuming

personal responsibility for one’s life and financial state. Dependency provides

financial stability and exemption from such stresses at the risk of external parties

not legitimising the disability, or of stigmatising the choice as morally inferior. The

proclivity to assume the disabled role is stronger when the perceived costs are

lower and the benefits higher. This can partly explain the prevalence of illness and

disability in low income, low education groups.

14

11 Wilmott

12 Aarts and de Jong 1992 p 62

13 Aarts and de Jong 1992 p 58

14 Luft, Harold S: 1975 pp 43 - 57

Page 9 of 144

link to page 11 link to page 11 link to page 11 link to page 11

3

Part 2: Barriers affecting return to work

3.1

OECD figures show that in every country unemployment was higher in 1989 than

in 1975, even though employment rose rapidly in the 1980s and in 1989 there were

more job vacancies. This led to rising wage inflation, increased interest rates, and

an abrupt end to the boom.

15 This implies there was a failure during the 1980s to

mobilise the unemployed. The 1990s provided a controlled experiment identifying

the factors leading to unemployment – some countries radically changed their

treatment of unemployed people while others did not. The various economic

practices implemented to address the numbers of unemployed have been generally

well documented but few have focused on the actual barriers facing individuals.

3.2

Many of the barriers facing a long term injured or unemployed person returning to

work are directly related to the individual. The way individuals cope with being out

of work has a direct relationship with their chances of returning to work. As

individuals react differently to the above factors, barriers against return to work are

established. These are described as personal barriers, compared with external

barriers which are imposed on the person outside their personal circumstances.

3.3

A British inquiry into inequalities in health cited being out of work as a potentially

major risk to both physical and mental health through:

•

Isolation, social exclusion and stigma;

•

Changing health related behaviour;

•

Disruption to future work career; and

•

Trapping people on lower incomes than available through work.

16

3.4

Most research on personal barriers to return to work focuses on demographic

characteristics, education and work experience. Recent research has identified

factors such as depression, substance abuse and even domestic violence as factors

that hinder long term employment prospects.

17 This research therefore has looked

further at barriers such as psychological functioning, stressful interpersonal

relationships, psychiatric disorders, and personal circumstances. Many of these

factors feature widely in the low-income and welfare populations.

A Personal factors

Attitudinal barriers

3.5

Unemployment, injury, and disability can have negative effects on psychological

and physiological well being. Job loss is a stressful event that threatens a person’s

sense of well being, takes away daily routines, lessens the sense of control people

have over their own lives, and creates changes in perceptions, emotions and

behaviours.

18 It can have deleterious emotional, behavioural, and physical effects.

15 Layard 2003 p 3

16 Acheson D (Chair) Independent Inquiry into Inequalities in Health Report (1998)

17 Zuckerman and Kalil 2000 Barriers to work section

18 Leana and Feldman 1995 p 1386

Page 10 of 144

link to page 12 link to page 12 link to page 12 link to page 12 link to page 12 link to page 12 link to page 12

It entails the loss of a valued role in society…often results in economic hardship

and corrodes one’s sense of mastery, personal identity and close relationship.

19

3.6

Job loss also represents a turning point in life. Some job losers will successful claim

a new work role, while others will be overwhelmed by the “cascade” of negative

financial events, an eroded sense of mastery, will suffer discouragement and

depression and may become a burden or source of stress for the families .

20

3.7

To balance this, there is substantial research indicating that the risks of depressive

symptoms, and the lack of motivation to undertake positive job search, are able to

be addressed by social interventions.

21

(a) Personal responses to stressful life events

3.8

People vary greatly in how they manage stress and uncertainty in their every day

lives. Each individual has available to differing degrees resources that help buffer

them from stressful situations or to lower the stress they would otherwise

experience. These include:

•

Individual skills, such as problem solving and social skills;

•

Levels of support (such as financial or family); and

•

Energy levels, such as physical health and positive outlook on life.

22

3.9

The greater a person’s reservoir of coping resources, the greater the likelihood that

they will cope with stress, uncertainty, and new situations. Conversely, fear or

worry of a negative interpersonal reaction can help that unwanted event to

happen.

23 Activities geared towards obtaining re-employment (such as job search

and retraining) are themselves quite stressful

24.

(b) Response to negative experiences

3.10 Social cognitive theory states that failure experiences can under-mine self-efficacy

and can lower outcome expectancies, eventually resulting in learned helplessness.

Many people without jobs feel frustration and discouragement over their failure to

get a job, and this can lead to negative perceptions of themselves. This negativity

then pervades their expectations of employment and sense of self-worth. They

may blame themselves for their injury or unemployment. The more depressed a

person is when beginning a job search, the less likely they are to:

•

Take the steps necessary to find a new job;

•

Keep their spirits up in the face of any rejections associated with job search

activities, and

•

Present themselves to potential employers in a positive light

25.

19 Price, Vinokur and Friedland 1995 p 22

20 ibid

21 Caplan, Vinokur and Price 1997 p 345

22 Lazarus and Folkman (1984)

23 Peale NV: The Power of Positive Thinking 1952

24 Leana and Feldman (1995): p 1384

25 ibid p 1383

Page 11 of 144

link to page 13 link to page 13 link to page 13 link to page 13 link to page 13 link to page 13

3.11 If a person was already pre-disposed to anxiety and depression, these factors will

impact on his or her acceptance of the injury and view of the future.

26

(c) Loss of status

3.12 Related to this is the concern over loss of status. A British trial to assist people

move off the Incapacity Benefit into employment

27 had mixed results when some of

the older beneficiaries refused to participate in some aspects of the trial as they

considered them “patronising and unsuitable for people who had years of

employment experience”. They were unwilling to consider “work which was

deemed to be insulting to their abilities.” This is in reality a failure of the

programme to meet the clients’ needs, and serves as a reminder that one size does

not fit all. Successful interventions are those designed to fit the needs of the

clients, not the needs of the agencies / experts.

(d) Lack of confidence

3.13 The British Department for Work and Pensions has researched various initiatives to

help return incapacity beneficiaries to work and, in one study, found that nearly

half of those beneficiaries actively seeking work had low confidence about working.

More than a third considered it unlikely that they would get a job because of their

health problems, and half of them thought that there weren’t job opportunities

available locally for people like them

28. A Canadian study found evidence of lack

of confidence because of age: “ If I did go back to work, given that I’m 48 years old,

who would hire me?”

29

(e) Apprehension regarding re-employment

3.14 Fear of the effect of re-employment on their injury or health, and of re-injury is

another common barrier for long term injured or ill workers against returning to

work. These are often unexpressed and sometimes unrecognised fears. “ If I knew

I could do it {work} then I would…but I’m so uncertain about it…what affect

would it have on your health”.

30 Losing a job through restructuring or continuing

ill-health creates another perceived potential stress of applying for unemployment

or disability benefits that acts as a disincentive to start seeking a job.

3.15 Fear of leaving the security of a benefit to take up paid employment is a significant

barrier

31. A British survey of more than 1600 beneficiaries revealed their top three

concerns were financial: having enough money to live on, coping financially until

the first pay (usually at the end of the month), and paying the mortgage/rent.

There was, again, a great deal of concern about reclaiming the benefit if the job did

not work out or last, due to the perceived complexities and capriciousness of the

rules. Fears that the job might not pay well, or that they would lose some of their

entitlements were also important concerns.

26 New York State Workers’ Compensation Board p 32

27 Heenan 2002 p 392

28 DWP: Short-term effects of voluntary participation in ONE

29 <www.returntowork.org/voices.html>

30 <www.returntowork.org/voices.html>

31 Woodland, Mandy and Miller 2003: p 64

Page 12 of 144

link to page 14 link to page 14 link to page 14 link to page 14

3.16 These fears were borne out by Harries and Woodfield’s research

32 on the

transitional experiences of people moving from benefit to paid employment. The

greatest disruption was the change in income cycles from weekly or fortnightly to

monthly. Making a monthly pay packet last for a monthly basis can be very

challenging. Often, too, there were additional costs related to employment, such as

childcare, travel, clothing and toiletries.

3.17 Perceptions of the likelihood of being able to move off income support are likely to

affect whether people actually do so. British research showed nearly two-thirds of

respondents felt trapped on income support

33. Family type, education, and ability

to “make ends meet” have a major effect on the likelihood of a welfare claimant

feeling trapped, whereas having a health or disability problem does not. Perception

of the local labour market was also a strong influence: nearly four-fifths of the

respondents believed their chances of finding a full time permanent job in their

areas was not very good. Lastly, workers who attach less value to employment

have significantly greater periods of unemployment

34.

Personal abilities

3.18 Research has identified several personal attributes (whether innate in the worker or

cultivated as a skill) which assist people cope with the stresses of injury and long

term unemployment. The converse is that the lack of these attributes helps create

barriers against return to work.

(a) Capacity to change.

3.19 With changes in technology, closure of work premises, changes in consumer

demand, some types of jobs are no longer available. These types of changes in the

labour market require workers and job-seekers to change as well. Some types of

injury rule out a return to pre-injury occupation, especially for manual workers. If

they are to return to work, these workers will have no option but to change their

occupation. Whether they succeed in finding employment will, to a large degree,

depend on their willingness to change and their ability to change.

3.20 Willingness to change is often seen as a generational issue: as people age, their

tolerance to change lessens and their resistance to change grows. Changing jobs

can put people outside their comfort zones and increase their stress levels,

especially when older people see youngsters performing tasks that they themselves

are unable to do.

3.21 The ability to learn is a key aspect of capacity to change. Employers involved in a

Philadelphia welfare-to-work scheme repeatedly stressed soft skills including good

attitudes, good work habits and ability to learn. “If some-one meets our criteria, we

can teach them the specific skills they need for our site”

35.

3.22 The US National Multiple Sclerosis Society has proven that changing physical job

demands and working conditions has helped MS sufferers cope with the effects of

32 Harries and Woodfield 2002 p 32

33 Shaw, et al 1996 p 122

34 WCRI Research brief 1996 Vol 12 No9 p 3

35 Hangley and Loizillon 2002 p 6

Page 13 of 144

link to page 15 link to page 15 link to page 15 link to page 15 link to page 15 link to page 15 link to page 15 link to page 15 link to page 15 link to page 15 link to page 15

their illness and maintain their employment

36. This has a parallel for injured

workers, whose injuries prevent them remaining in their pre-injury occupation.

(b) Personal expectations

3.23 The worker’s expectation of his or her performance is probably one of the biggest

predictors of success in returning to work. The National Multiple Sclerosis Society

has also proven that personal attributes such as hope, personal control and sense of

humour helped MS sufferers cope with the effects of their illness and maintain their

employment. A study conducted with the Commonwealth Employment Service in

Australia, found a significant relationship between those who blamed themselves

and those remaining unemployed

37.

3.24 Acceptance of residual “scars” from injury is an important ability facing those who

return to work. Developing self-awareness and acceptance of deficits resulting

from traumatic brain injury is the key aspect in the process of rehabilitation, and

those unable to do this will not be able to become productive in the community

38.

(c) Education

3.25 Basic literacy and numeracy skills are key requirements for most jobs

39. Those with

numeracy and/or literacy problems tend to take longer to regain employment after

injury or long term unemployment. More than half the beneficiaries (whether on

unemployment or invalid benefit) in one study

40 had no school qualifications at all,

and more than three quarters of them had left school by the age of 16. An

American study identified limited proficiency in English as a further barrier

41. In

this study, 41% of the TANF (Temporary Assistance for Needy Families) caseload

in Los Angeles County had limited proficiency in English, reflecting the fact that

17% of the case load were foreign-born.

3.26 Poor English skills were identified in a study of New Zealand Employment Service

long-term clients,

42 as well as in a study of its own claimant group by ACC’s then

subsidiary Catalyst

43. Claimants who could neither read nor write English could

not understand any information given to them by the two agencies. Statistics NZ

figures from the 1996 Census show that less than 2% of New Zealand residents do

not speak any English, compared with about 5% of the American population,

according to US Census 2000 data

44. Studies in the US have shown a strong

connection between language ability, employment and earnings.

45

3.27 New Zealand and international studies cite low levels of education as a significant

barrier to regaining employment.

46 In America, the lack of a high school diploma

can make it difficult for individuals to find jobs, either because the diploma is a

36 source

37 Waters and Moore 2001 p 601

38 Ben-Yishay and Lakin: Structured group treatment for brain injury survivors

39 DWP: Well enough to work?

40 Woodland, Mandy and Miller 2003: p 60

41 Goldberg 2002 p 4

42 NZ Employment Service 1996

43 Pack Margaret: internal ACC report 2002

44 Wrigley et al August 2003

45 ibid

46 NZ Employment Service 1996

Page 14 of 144

link to page 16 link to page 16 link to page 16 link to page 16 link to page 16 link to page 16 link to page 16

pre-requisite for the job, or because individuals without the skills of a high school

graduate cannot perform the duties associated with many jobs.

47 A Michigan study

showed that only 39% of women with no high school qualification worked at least

20 hours a week, compared with 66% of women with a high school qualification

48.

A 1996 study of employers’ entry-level job requirements found that most required

employees to perform one or more of these following skills on a daily basis:

•

Reading and writing paragraphs;

•

Dealing with customers;

•

Doing arithmetic; and

•

Using computers

49.

3.28 Other American studies indicated that these skills were beyond the abilities of the

average welfare recipient or high school drop-out, and therefore reduced markedly

their ability to gain any employment

50. The American Testing Service estimated

that 40% of welfare recipients had such low levels of literacy that they were unable

to complete tasks such as completing applications for social security.

51

3.29 Compounding this barrier to employment is that many people lacking literacy skills

are very aware of the lack, and the problems it can create. Over time, they have

developed sometimes quite sophisticated techniques to conceal the lack so that

even case managers and career advisers are unaware of their lack of literacy skills.

3.30 Higher education / higher intelligence are important factors. In Canada,

technological skills and advanced education are becoming minimum requirements

for obtaining and retaining employment, while jobs in areas such as manufacturing

are becoming scarce

52. As products and job skills become outdated, those with

computer, maths and literacy skills are favoured. Most studies have found that

better educated workers are more likely to return to work than less educated

workers, and this is backed up by the most recent BRC New Zealand survey of long

term claimants who had exited from the ACC scheme.

53

3.31 Reasons for the higher rates of return to work for those better educated include:

•

A physical impairment is less likely to have an impact as better educated

workers jobs are usually not physically demanding;

•

Better educated workers usually have more control over the manner in

which they perform their jobs, so are able to adapt their activities to

accommodate physical limitations; and

•

Generally employers have invested more in better educated employees

which provides an incentive to make their own accommodations in order to

retain these workers.

47 Goldberg, 2002 p 4

48 Danziger et al, 2000 p 32

49 Holzer 1996

50 Danziger et al, 2000. P 5

51 Brown 2001 p 88

52 Bunch and Crawford, 1998 p 25

53 BRC research report: Return to sustainable earnings January 2003

Page 15 of 144

link to page 17 link to page 17 link to page 17 link to page 17 link to page 17 link to page 17 link to page 17 link to page 17

3.32 More than two-thirds of the respondents in the New Zealand Employment Service

survey of long term unemployed in 1996 acknowledged that lacked appropriate

skills or work experience, while 22% admitted they had literacy or numeracy

problems.

54

3.33 In 1997, New Zealand participated in the International Adult Literacy Survey (IAS),

which was the first internationally comparable estimate of literacy skills in the

adult population. The IALS tested respondents from 12 OECD countries on prose

comprehension, comprehension of graphs, timetables, and charts, and applying

arithmetic operations. The results showed that abut one in five workers had

pressing literacy needs. Almost half of all adults aged 16 – 65 were estimated to be

at the lowest levels of ability.

55

Employability

3.34 Employability is identified as another barrier against return to work

56. While there

is no standard definition of employability, it encompasses gaining and maintaining

employment, having and deploying the appropriate knowledge, attitude and skills,

and presentation (both of qualifications and experience, and during job interviews)

that employers value. It is having job skills and credentials which cut horizontally

across all industries and vertically across all jobs from entry level to chief executive.

Since it can be difficult for employers to obtain reliable information on

employability, many rely upon general impressions of the people concerned and

stereotypes of group to which they belong

57.

3.35 Several American studies found that many of the longer term unemployed were

simply not “work-ready” in that they did not understand or follow workplace

norms or behaviours

58. Many participants in special programmes failed because

they did not understand the importance of punctuality, the seriousness of

absenteeism, and either resented or misunderstood the lines of authority and

responsibility in the workplace.

3.36 That employers value generic employability skills above specific occupational skills

is a well supported finding, and applies to all size companies, to the public and

private sectors, and at all levels of management.

59 Studies continue to confirm the

need for employees to have social skills, positive attitudes about work, and basic

communications skills. Other research showed that employers discharge or fail to

promote workers because of behaviour reflecting an inadequate work value or

attitude, rather than because of a deficiency in job skills or technical knowledge.

60

3.37 A New Zealand trial programme

61 targeted to assist long term unemployed was

based on the contention that many long term unemployed had entrenched personal

and social problems that inhibited their ability to participate in the labour market.

The actual barriers identified during the development of the programme included:

54 Parker 1997 pp 68-9

55 Department of Labour p 27-8

56 Hillage J and Pollard E (1998) Executive summary

57 van den berg and van der Veer p 178

58 Danziger et al, 2000 p 5

59 Cotton p3

60 Gregson and Bettis 1991

61 Wehipeihana p 5

Page 16 of 144

link to page 18 link to page 18 link to page 18 link to page 18 link to page 18 link to page 18

•

Alcohol or drug dependency problems;

•

Anger management problems;

•

Disruptive or dysfunctional family situations;

•

The psychological consequences of domestic violence or abuse, either

historical or current;

•

Illiteracy - often well disguised or hidden;

•

A bad reputation in the local small community; and

•

Unrealistic notions about the income generating potential of hobbies or

artistic pursuits.

3.38 For some participants in the programme, the barriers were not immediately

apparent to the facilitators, or known or acknowledged by the participant. The

process of identifying barriers was described as “akin to peeling an onion – as soon

as one barrier was identified and overcome, another deeper issue would rise in its

place…the surface barriers to employment were often mere symptoms of much

more deep seated problems”.

3.39 One of the facilitators for the NZ programme expressed concern that case managers

are not able to see their clients often enough, or for long enough, for barriers such

as these to become evident. Further, the computerised assessment tools as used by

Work and Income cannot take into account any problem or issue that is not

employment related. The lack of follow-up after attendance at programmes often

left participants feeling even less motivated than they were before starting

programmes

62.

Health factors

(a) Pain management

3.40 Coping with pain has long been cited as a reason not to work. Pain-related

behaviours that communicate a person’s pain to others have often been supported

inadvertently by the healthcare system

63. Patients in pain may get increased

support and sympathy when they express suffering, which then increases “pain

behaviour”. One of the goals of pain rehabilitation should be to reduce the effects

of demotivating factors for patients for return to work. Families can inadvertently

reinforce an injured person’s sick behaviour and delay any return to work simply

because they are trying to help some-one they love

64

3.41 Multi-disciplinary pain management programmes give promising results in helping

injured workers back to work

65 66, with one limited study

67 showing that such a

programme was more effective for short-term patients (up to 12 months) than long

term patients. American studies show that increasing patients’ own resources to

deal with pain situations can be an effective way of increasing self-confidence and

62 ibid p 24

63 Gard and Sandberg 1998.

64 McIntosh, Melles and Hall 1995 p 199

65 Morley et al: …randomised control trials of cognitive behaviour therapy for chronic pain

66 Flor et al: Efficacy of multidisciplinary pain treatment centers

67 Marhold, Linton and Melin 2002: p 73

Page 17 of 144

link to page 19 link to page 19 link to page 19 link to page 19 link to page 19 link to page 19 link to page 19

improving motivation to return to work

68. More research is scheduled to assess the

effects on long term patients. In New South Wales, it is accepted that a significant

proportion of back injury cases will never recover completely and that their back

pain will need to be controlled and adapted to.

69

(b) Use of cigarettes, drugs, and alcohol

3.42 Smoking is an activity which can impact negatively on an injured worker’s return to

work. Smokers are already at risk of lung cancer, heart disease, emphysema, and a

shorter life expectancy. US Army research during an eight week basic training

programme with new recruits

70 showed that, even after controlling for other factors

which might influence the risk of injury, the smokers were 1.5 times more likely to

suffer fractures, sprains and other physical injuries than non-smokers. They had

also had more previous injuries and illnesses, were less physically active, and were

less physically fit than the non-smokers. Risk of injury for smokers was high,

despite the fact that recruits were forbidden from smoking during the training

period.

3.43 Alcohol is connected with over half of all traumatic brain injuries. If some-one

used alcohol or other drugs before they were injured, there is a good chance that

the problem will continue afterwards.

71

3.44 Injured workers are already at risk of infection and other health problems: smoking

increases the likelihood, placing them at even higher risks. Rehabilitation

specialists dealing with people with spinal cord injuries

72 advise them to cease

smoking because of:

•

Difficulties in breathing, especially difficulties in expelling air because of the

build-up of mucus and other secretions in the lungs;

•

Increased chances of developing stomach ulcers, poor circulation, pressure

sores and bladder cancer;

•

Decreases in the body’s supply of vitamin C, so skin wounds heal more

slowly; and

•

An impaired ability to cough, leading to respiratory diseases (20% of

quadriplegics die because of an inability to cough).

3.45 There is also a higher prevalence of smoking, exposure to passive smoking, and a

heavier consumption of alcohol among people who are unemployed.

73

3.46 Drug and alcohol related problems also feature as a barrier to re-employment of

long-term unemployed. While the exact definitions of drugs and alcohol problems

vary widely, and accurate estimates of affected numbers are hard to obtain, there is

general consensus that dependency and abuse does create problems, especially in

keeping a job.

74 Former alcohol and drug abusers continue to have low self-esteem

68 Gard and Sandberg 1998

69 Mills and Thornton 1998 p 594

70 Gardner John W: Press statement Smoking linked to physical injuries, 16 March 2000

71 CTS Rehabilitation Specialists Programme website: http://p2001.health.org/RS01/MODULE4PM.htm

72 CTS Rehabilitation Specialists Programme website: http://p2001.health.org/RS01/MODULE4PM.htm

73 Elkeles and Seifert 1997 pp 41-45

74 Institute for Research on Poverty: The New face of Welfare

Page 18 of 144

link to page 20 link to page 20 link to page 20 link to page 20 link to page 20

which hampers successful employment and weakens their ability to make

successful transitions from welfare to work.

3.47 In a random analysis of 250 case files, ACC subsidiary Catalyst found addiction

issues. Claimants had self-medicated using prescription and /or recreational drugs

and alcohol to manage pain. The ensuing dependency on those substances

hampered rehabilitation.

75

(c) Mental health

3.48 Mental health is a less recognised barrier to return to work, and research is still

underway to identify what mental health problems affect people’s ability to return

to work in order to make recommendations for policies to address this.

3.49 Studies suggest that low income single mothers are particularly at risk of significant

mental health problems when they lose their jobs

76. Importantly, however women

in this group are no more likely than their employed counterparts to be alcohol or

drug dependent.

77

3.50 The term “post traumatic stress disorder” (PTSD) was adopted in 1980 to describe

the pattern of symptoms exhibited by some people who experienced a traumatic

event. Traumatic events range from high profile disasters / bombings to personal

events such as assault, robbery, motor vehicle crash or an accident. Any or all of

three types of symptoms may be experienced by PTSD sufferers including:

•

Persistent flashbacks;

•

Avoidance of any reminders of the event; and

•

Increased alertness /hyper vigilance.

3.51 Although these reactions do not always lead to a diagnosis of PTSD, the trauma

symptoms that individuals experience can be severe enough to affect people’s day

to day lives and their ability to work.

78

3.52 People with existing mental illnesses are generally thwarted by three main barriers:

a)

Their psychiatric professionals tell them they won’t have to work, or cannot

work because of their illness;

b)

People are afraid of losing their benefits; and

c)

People have difficulty communicating with their employers, whether to tell

them about their illness, and how to do that.

79

3.53 Health professionals in New South Wales have identified that the costs of private

psychiatric services are high, while publicly funded mental health services may give

low priority to problems such as anxiety, depression, emotional stability and social

75 Pack 2003 p 13

76 Tainter 1998 p 1

77 DeGroat 1998 Press statement 23 November 1998

78 Rick, Young and Guppy Executive summary

79 Granger Barbara of Matrix Research Institute, on website <www.matrixresearch.org>

Page 19 of 144

link to page 21 link to page 21 link to page 21 link to page 21 link to page 21 link to page 21 link to page 21

isolation.

80 In many cases, more unemployed people live in geographic areas

where public health services may be in limited supply.

3.54 There is growing evidence that under-employment and inadequate employment

also lead to poor health and mental health outcomes.

81 Under-employment

includes:

•

Working fewer hours than desired

•

Being underpaid

•

Being unable to find work that fits the individual’s skills and education.

3.55 These all constitute barriers against return to sustainable employment, and are

addressed elsewhere in this report.

Refusal to accept jobs

3.56 Some men do not take part-time or temporary jobs because such jobs do not pay

much more than they get remaining on welfare benefits

82, while others with

industry specific experience are likely to wait for re-employment in jobs similar to

the ones they used to have, rather than accept a less well paid job in another

industry.

83 Some people price themselves out of jobs by refusing to accept the

levels of wages offered.

3.57 Most jurisdictions require injured workers to co-operate in their rehabilitation.

Some workers use their right of review of their individual Return to work /

Rehabilitation plans to stall a return to work. Workers respond to incentives to

exaggerate or falsify claims of work-related injuries, including that numbers of

claims filed increases with benefits available, and some workers overstate the

limiting effects of injuries in order to delay return to work.

84 Following a study of

3700 workers with back problems, the researchers commented on “the relative ease

with which back pain can be overstated by patients seeking disability benefits and

time off work.”

85

Age, gender, ethnicity

(a) Age

3.58 Older workers are much less likely to return to work than younger workers

86.

American experience of the corporate downsizing in the late 1980 and early 1990s

was that proportionately more older workers were laid off, and less investment was

made in training or retraining older workers. These practices put older workers at

a disadvantage, even before they have an injury and seek re-employment or

retraining. As people move into their 50s and 60s, they are more likely to

experience health related problems, and an injury can have the effect of moving

them into early retirement.

80 Harris et al 1998 p 292-3

81 Price 2000 p 5

82 Borooah 2001 Section 4.1

83 McCormick B: Unemployment Structure and the Unemployment Puzzle 1991

84 Johnson, Baldwin and Butler 1998 pp 39 - 62

85 ibid p 28

86 Baldwin and Johnson 1998 pp39 - 62

Page 20 of 144

link to page 22 link to page 22 link to page 22 link to page 22 link to page 22

3.59 In contrast, the majority of executives and leaders are older adults.

87 Work

performance does not decline with age until well into the seventies and beyond.

Given that there are no major health problems, most people remain at the same

level of ability up to very late life. There are, however, age related changes in the

central nervous system which may impact on speed of processing information and

efficiency of processing complex information. The correlation is generally more

between cognitive ability and work performance. Learning, memory, intelligence

and speed are related to overall cognitive ability. Given that most jobs do not

involve maximum levels of performance, most older workers can perform their

work tasks satisfactorily.

3.60 Age does affect individuals differently: older workers tend to prefer more

responsibility, interesting work, and attention demands

88 while younger workers

prefer autonomy and social opportunities. Some studies have shown that younger

workers may lack the knowledge to make accurate judgements about the likelihood

of efforts paying off.

3.61 Human Resources Development Canada

89 identified a specific list of barriers faced

by older workers attempting to return to the workforce:

•

Lack of job search skills – older workers tend to have relatively steady

employment histories, and so have not used the skills needed for a

successful job search. Thus their job search techniques tend to be outdated,

and their approaches generally less innovative than younger people;

•

Absence of relevant skills for positions in the growth industries – this

includes levels of literacy, numeracy, and technical and computer skills;

•

Level of formal education. In today’s environment, low educational

attainment greatly hampers the abilities of workers to market themselves to

prospective employers;

•

Older workers are also generally less willing to relocate for an employment

opportunity than younger individuals;

•

Related to this is the unwillingness of many financial institutions to approve

long term mortgages to individuals with limited years of employment

remaining to them.; and

•

Capacity for acquiring training and professional development, or perceived

capacity for skills upgrading.

3.62 While any one of these may relate to any person seeking to return to work after an

absence, older workers tend to face several of them concurrently. Some older

workers feel social pressure to withdraw from the workforce in order to provide job

openings for younger workers, and thus to reduce the unemployment rates among

younger individuals

90. A British survey found that more than half the beneficiaries

over 55 years of age did not want to work

91. However, while many displaced

workers choose retirement over job search and/or retraining, a considerable

number are simply not financially or emotionally prepared for retirement.

87 Sterns and Miklos: p 255

88 Phillips, Barrett and Rush: job structure and age satisfaction

89 Human Resources Development Canada Technical Report #1: 1997 Section 1.1

90 HRDC: Lessons learned – a review of older worker adjustment programs 1997 Section 7.2

91 Woodland, Mandy and Miller 2003: p 22

Page 21 of 144

link to page 23 link to page 23 link to page 23 link to page 23 link to page 23 link to page 23 link to page 23 link to page 23

3.63 A Canadian study on the needs of older workers indicates that the older individuals

who participate in active approaches to improving re-employment opportunities

appear to benefit from programmes which are more client centred. Programmes