Auckland Transport

Auckland Transport

Auckland light rail peer review -

Part B: options and assessment

(Draft 2)

21 July 2015

N207/Rep/1553

Ian Wallis Associates Ltd

[email address]

link to page 3 link to page 4 link to page 11

Ian Wal is Associates Ltd

Contents

1. INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................................... 3

2. OPTIONS AND ASSESSMENT - PEER REVIEW .................................................................................. 4

ANNEX A: Study Objectives ................................................................................................................... 11

IWA/N207/Rep/1553

21 July 2015

2

Ian Wal is Associates Ltd

1. INTRODUCTION

This paper has been prepared for Auckland Transport by consultants Ian Wallis Associates (IWA), as

part of a peer review of AT’s proposals for a light rail network for Auckland.

The paper is one of three papers prepared by IWA for this peer review.

This paper (B) is concerned with

options and their assessment. Specifically it addresses the following

aspect of the peer review task:

“…

the reliability of the options analysis results against the achievement of the

study objectives, including whether there are further viable options that could be

considered and appropriateness of the MCA for the purpose used – to identify the

broad strategic option for further development.”

For conciseness, our review of this aspect is provided in tabular form, within the following sections:

• A: Project Purpose and Objectives

• B: Problem Definition

• C: Range of Options Considered

• D: Selection of ‘Short’ List Options

• E: Framework for Option Assessment

• F: Assessment Objectives and Criteria

• G: Assessment Scoring Methodology

• H: Assessment Scoring Application

• I: Approach to Assessment Weightings (and Sensitivity Tests)

• J: Summary of Option Assessment Findings.

The other two papers in this peer review set cover the fol owing aspects of the AT proposals:

Paper A: Robustness of the deficiency analysis. This paper focuses on demand and capacity analyses

regarding the maximum number of buses that can practically and reliably be accommodated on main

routes in the isthmus and city centre.

Paper C: Cost estimates. This paper reviews the estimates of LRT infrastructure costs, vehicle capital

costs and operating costs for the LRT proposals relative to the costs for the bus-based base case.

IWA/N207/Rep/1553

21 July 2015

3

link to page 4 link to page 4

Ian Wal is Associates Ltd

2. OPTIONS AND ASSESSMENT - PEER REVIEW

Summary of AT Work Undertaken

Peer Review Comments

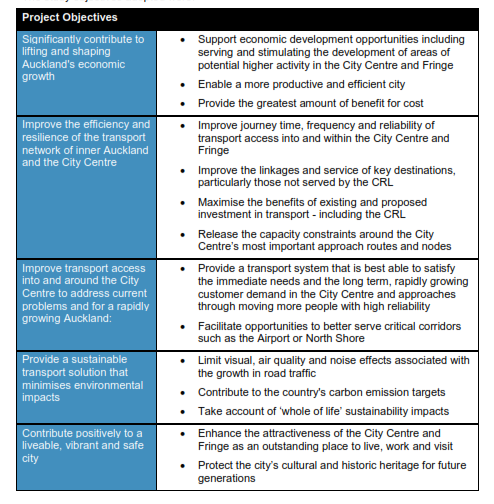

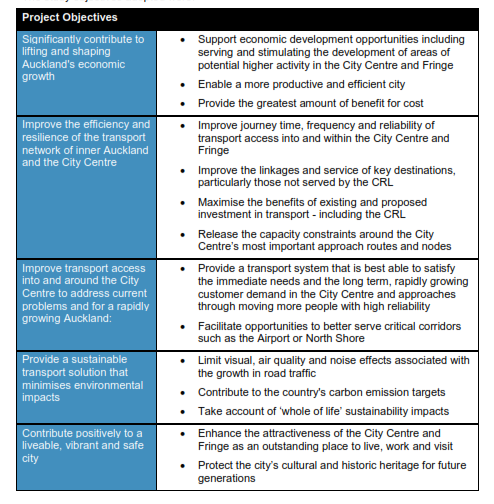

A. Project Purpose and Objectives

We were advised by AT

1 that the

purpose for this • We note the ‘two-pronged’ nature of this purpose

(CCFAS2) project has been defined as fol ows:

statement, ie focusing on: (i) providing an effective

“

Provide an effective transport solution for those

transport solution for inner Auckland that supports

parts of inner Auckland and the City Centre that

growth requirements; and (i ) maintaining the

cannot be served by the heavy rail network, with

amenity of the city centre streets, in particular in the

CRL; that supports growth requirements in a way

light of the prospect of an increased number of

that maintains or enhances the quality and capacity

buses on these streets to cater for future public

of the City Centre streets; and thereby resolve the

transport demand.

outstanding issues identified in CCFAS including the • Taken at face value, these objectives/sub-objectives

impact of a high number of buses on urban

are consistent with the ‘two-pronged’ (‘balanced’)

amenity.”

statement of project purpose: objective 1 focuses on

economic development; objectives 2 and 3 on

AT also advised that six

objectives had been set for

transport system accessibility and efficiency

the project, in summary as fol ows (full in/around the city centre; objective 4 on

objectives/sub-objectives set out in Annex A):

sustainability and environmental impacts of the

1. Significantly contribute to lifting and shaping

transport system; objective 5 on city ‘liveability’,

Auckland’s economic growth

including restraining transport costs and congestion

2. Improve the efficiency and resilience of the

levels; and objective 6 on implementability and

transport network of inner Auckland and the

‘stageability’.

City Centre.

• However, we note that, in interpreting these

3. Improved transport access into and around

objectives, the further advice from AT indicates a

the City Centre to address current problems

somewhat different balance between the objectives

and for a rapidly growing Auckland.

– focusing primarily on city ‘liveability’ and amenity

4. Provide a sustainable transport solution that

of the city central area.

minimises environmental impacts.

• This direction wil clearly have implications for the

5. Contribute positively to a liveable, vibrant and

option assessment framework and criteria (as

safe city.

discussed in a later section).

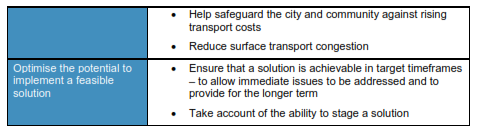

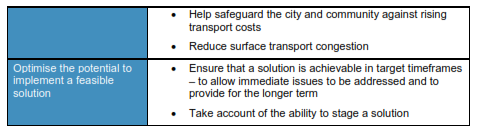

6. Optimise the potential to implement a feasible

solution.

In relation to the stated project purpose and

objectives, we were further advised by AT

2 as

fol ows:

“

You wil see the emphasis given (in the project

purpose) to urban amenity. In this context I can

confirm that achievement of objectives 4 and 5 is

given particular weighty in accordance with the

guidance of the AT executive. Objective 1 should

also be understood to have an amenity dimension –

we understand that enhanced economic activity in

the City Centre is not seen as likely to occur unless

the aesthetical qualities improve.”

B. Problem Definition

The definition of the problem that this project is • We note that the ‘problem definition’ as outlined

intended to address is essential y summarised in the

in the Jacobs’ Deficiency Analysis paper is entirely

based on a ‘do minimum’ transport scenario for

year 2046: this Do Min case includes CRL and the

1 Email John Al ard to Ian Wallis, 20 July 2015.

2 Ibid.

IWA/N207/Rep/1553

21 July 2015

4

link to page 5 link to page 5 link to page 5

Ian Wal is Associates Ltd

CCFAS2 ‘Deficiency Analysis’ paper prepared by the

new bus network, but otherwise minimal changes

AT Project Team

3.

to the existing PT system. Its estimation of future

That paper focuses on the transport issues and

bus service levels is based on continuing to use

problems expected to occur in the southern

‘standard’ size buses (c. 50 passenger capacity) in

corridor and the central area over the period to

the corridors of interest, despite the use of much

2046. Its analyses are based primarily on transport

larger capacity vehicles elsewhere in AKL. Thus it

model ing using the APT model. Its findings on these

paints a ‘worst case’ picture of the number of

issues and problems are summarised as fol ows:

buses in future – which, prima facie, could be

“In summary, the deficiency analysis for CCFAS2 has

substantial y improved upon by use of a smal er

highlighted that capacity on public transport bus

number of larger (eg double-decker) buses. Its

services is likely to be a real issue, particularly as

results need to be interpreted in that light.

they near the City Centre and then within the City

Centre itself. The problem of delivering sufficient

capacity is already evident by 2026 on some services

and corridors and by 2046, nearly twice the number

of buses currently operating would be required to

meet the demand for travel by bus. The central

isthmus is the main area where issues are evident as

services entering the City Centre at Symonds Street

struggle to cope with demand and Symonds Street

itself wil struggle to cope with the required bus

volumes beyond the very early 2020s.”

In regard to issues relating to the amenity of the City

Centre area as affected by transport, a separate

report was prepared, focusing on the ‘amenity

capacity’ of central area streets in terms of bus

volumes.

4 Arguably, a more balanced summary of the

problems is provided in a recent AT document

5:

•

Increasing congestion in the City Centre is

reducing urban amenity and liveability.

•

Constrained access to the City Centre wil

limit economic growth and reduce the

region’s productivity.

•

Inefficient use of city centre street space

wil restrict accessibility, mobility and the

city’s economic competiveness.

C. Range of Options Considered

The main outcome of the long list review workshop • We have reviewed the paper summarising the

[10 Oct 14, AT34] was the selection of five suburban

findings from the long list workshop and have no

routes for further assessment (Dominion, Manukau,

issues with selection of these five suburban

Sandringham, Mt Eden, Remuera Roads). A variety

routes/corridors and options for their extension

of city centre streets/ corridors were also in/through the CBD. We note that these options are

nominated as providing potential routes for described in various places as 'Long list options',

operation of the suburban services in/through the

although arguably at that stage they were no more

CBD.

than specifications of potential corridors/roads to

be used rather than future network or service

options.

3 CCFAS2 – Deficiency Analysis (ref ZB01598), Jacobs for AT, 9 January 2015.

4 Built Environment and Amenity Technical Paper (draft), Jasmax for AT, November 2014. [IWA 65]

5 LRT Technical Advisor RoI (ref 303-15-791-PS), AT, July 2015.

IWA/N207/Rep/1553

21 July 2015

5

Ian Wal is Associates Ltd

D. Selection of ‘Short’ List Options

Fol owing the long list review work (as above), AT • While a multitude of 'short' list options could be

prepared a Short List Summary Paper [13 Feb 15, AT

defined, consistent with the outcomes from the long

61.1]. This paper

“developed a short list of 10

list review workshop above [AT 34], we consider

network options that would enable a range of

that the 10 short list options defined are likely to

combinations of modes to be evaluated”. Of these

have covered the range of more promising options

10 options, five are focused on LRT (involving

(recognising that the options might be further

different combinations of the five suburban refined in the subsequent stages of the study).

corridors identified earlier), two involve bus on-

• However, we note that we have not identified any

street (using double-decker buses), one involves

written material that explains and justifies the

BRT (predominantly on-street), one involves a

selection of these 10 options from the wide range of

combination of heavy rail and bus, and one a

possibilities: this short list assessment is a significant

combination of heavy rail and LRT. The five LRT

step in the overal study and should be appropriately

options al involve different combinations of the five

documented. We also note that while five LRT-based

suburban corridors identified earlier, and al would

options were included in the short list, only one of

run into the CBD via Queen and/or Symonds

these options was 'mirrored' by a corresponding

Streets.

BRT-based option - whereas there appears to be no

reason why the other four LRT options were not

similarly 'mirrored'.

• We further note that, in the specification/discussion

of the options, the aspect of bus capacity gets only

brief mention. Our understanding is that: the Do

Min option is based on ‘standard’ size buses; options

1, 2 and 3 involve double-decker buses; other

options (including the BRT option 7) most likely

involve standard size buses (although this is

unclear). Given the demand forecasts for 2046, we

would have expected that the main bus routes in al

options would be operated by double-decker buses.

E. Framework for Option Assessment

A multi-criteria analysis (MCA) approach was taken • We support in principle the use of the multi-criteria

to the comparative assessment (evaluation) of the

analysis (MCA) framework for the study’s

10 ‘short list’ options. This involved [refer AT27, 23

comparative assessment of options against the

Dec 14]:

range of objectives. However, we have considerable

• Specification of objectives (8).

concerns relating to some of the details of

• Specification of criteria relating to each application of this framework, as noted in the

objective (over 50 criteria in total, within the

fol owing sections.

8 objectives).

• We note that the MCA application in this case is

• For each criterion, specification of an more ambitious and complex than most such

appropriate measure and the data source for

applications, in terms of having:

this measure.

o A relatively large number of objectives (8)

• Specification and then application of a relative

o A relatively large number of criteria (> 50),

rating scale (2, 1, 0, -1, -2) for rating the

many of which significantly overlap (hence may

performance of each option against each

result in double-counting) and some of which

criterion.

contradict others.

• Selection and application of weightings for

o A relatively large number of options (10) to be

each objective and the criterion within the

compared

objectives, and hence derivation of the • We have been unable to identify any statement as

weighted sum score for each option under

to the role of the MCA, potentially as part of a wider

each set of weights.

assessment of the most promising options – which

• Drawing conclusions from these results on the

would be expected to include a business case

relative performance of the options, and the

analysis, including an economic appraisal. By

sensitivity of the performance results to a

default, the impression is given that the MCA

range of weighting assumptions.

assessment comprises the

total assessment of

IWA/N207/Rep/1553

21 July 2015

6

link to page 7

Ian Wal is Associates Ltd

options, rather than only a component of a wider

assessment process.

F. Assessment Objectives and Criteria

The assessment (evaluation) framework has eight • The eight objectives used in the assessment differ

‘objectives’. Six of these relate to ‘benefits’ - of

from the six study objectives defined earlier (refer

which three relate directly to transport (city centre

Annex A). One reason is that an additional objective

access, city centre mobility, regional movement),

(cost) has been included for assessment purposes,

two to environment and one to economic but was not included in the original objectives. .

performance. The seventh objective relates to • Apart from that, there is only a broad

implementation and the eighth to cost aspects.

correspondence (no more) between the other seven

assessment objectives and the six project objectives.

Further, there is no clear correspondence between

the assessment criteria and the project sub-

objectives. We cannot see any good reason for these

differences, particularly at the top (objective) level,

and have not identified any documentation to

explain the reasons.

• Further, we note that the eight assessment

‘objectives’ are not couched in ‘objective terms’, but

are merely topic heading in the spreadsheet

analyses.

• We note that, of the eight objectives, seven are

essential y measuring ‘benefits’ (to transport users,

the community, the environment, etc) while only

one is measuring ‘costs’ (to the public sector).

Within the eight objectives, over 50 assessment • The > 50 criteria is a relatively large number for such

criteria are specified. For each objective, a

assessments, and tends to give rise to issues of

corresponding measure is defined along with the

double (or triple) counting and interpretation. For

data source to be used in measuring performance.

example, criteria 1.02, 1.04 and 1.07 appear in part

to double-count similar effects, and in part to point

in contradictory directions. We have not attempted

to review/critique every individual criterion and its

associated measures.

G. Assessment Scoring Methodology

The assessment scoring is set out in two main • The ‘Do Minimum’ should be defined somewhere

spreadsheets [AT27, Evaluation framework v O9,

(we have not sighted any definition). We are unclear

sheets ‘Assessment’ and ‘Scored version’]. It

whether the Do Min is a realistic option over the

involved ranking (rating?) performance against

longer-term (eg 2046): if not, we suggest it should

each criterion on a relative scale, comparing every

be replaced, as the assessment base case, by a

option against the Do Minimum case. The rating

minimum cost variant that would be realistic

scale used was +2, +1, 0, -1, -2, using only integer

(maybe this is option 1?)

6

scores and where the Do Minimum was scored 0 • We have seen no statement as to the ‘assessment

(zero) in al cases.

year’ adopted but assume it is 2046, representing a

medium/long term year for which model estimates

are available and by which the full scheme is

assumed to have been implemented.

• The 5-point assessment scale is relatively crude for

a project of this type: a 7-point scale may be worth

consideration.

• Where quantitative assessments are possible/

available against criteria, it would be helpful to

include these in the assessment. Then, as required,

they can be also expressed in terms of points

6 AT advises that option 1 is being used as the ‘base case’ for economic assessment purposes in work currently in progress.

IWA/N207/Rep/1553

21 July 2015

7

Ian Wal is Associates Ltd

(usual y assuming a linear relationship between the

quantified estimates and the corresponding point

scores). This wil give more confidence that relative

performance figures (e.g. out of the transport

model) are being reflected consistently in the rating

scores.

• The above point is considered especial y important

in the case of the cost objective. It is not readily

apparent to people examining the results that the

total cost range between the options is very

substantial, probably in the order of $2.0 bil ion (PV

terms) over the economic life of the project. This

significant amount (of similar order to the total costs

of CRL) tends to get lost in the way that the

assessment results are presented.

H. Assessment Scoring Application

Each option was assessed against each criterion on • We have not attempted to review the awarded

the 5-point scale (relative to Do Min = 0). The Excel

scores in any detail. However, we do have some

worksheet [AT27, Assessment] sets out the scores

reservations from the limited checks made (noting

awarded with a brief comment as to the basis for

that no two parties are ever likely to agree

them.

completely on the relative merits of options against

al criteria).

• To review the assessment findings on the relative

merits of BRT v LRT, we specifical y compared option

5 (ful LRT network) and option 7 (ful BRT network).

A view quite often expressed is that anything an LRT

solution can achieve, an equivalent BRT option can

also achieve, but at significantly lower total costs

(capital and operating, in PV terms). This review

found that, according to the assessment results,

option 7 performs substantial y worse than option 5

against most objectives (1, 2, 4, 6 and 8). In

‘unweighted’ terms (al objectives weighted equal y,

and al criteria within any objective weighted

equal y) option 7 performs no better than option 1

(double decker buses, on-street operation). We find

these relative results somewhat unlikely, which

raises more general concerns about the assessment

scoring and weightings applied (refer fol owing

section).

• We also note that, under the base assessment (all

objectives given equal weighting), the 10 options fal

into two groups: options 1, 2, 3 and 7, with weighted

sum scores in the range -0.6 to 0.7; and the other six

options, with weighted sum scores considerably

higher, in the range 1.7 to 2.8. We observe that al

six high-scoring options are focused on LRT mode;

whereas the four lower-scoring options are focused

on bus mode (with one including a limited heavy rail

extension, Mt Roskil Spur). The conclusion that may

well be taken from this scoring is that, for the area

under study, LRT-based PT

is very considerably

superior to bus-based PT services on the assumption

that

al objectives are equal y weighted. This result

is somewhat surprising in our view.

IWA/N207/Rep/1553

21 July 2015

8

Ian Wal is Associates Ltd

I. Approach to Assessment Weightings (and

Sensitivity Tests)

Our understanding is that the ‘base’ assessment (A) • The results we have inspected [AT27, v9: Scored

results give equal weight to each objective (ie a one-

version] appear to be identical for equal and

point score difference between options is given the

unequal criteria weightings (ie assessment (B) is

same weight across all objectives); and also equal

identical to (A), (D) identical to (C). This suggests

weight to al criteria within any objective.

that the unequal criteria weightings have not been

Sensitivity tests have also been undertaken on the

applied in practice.

weighting of objectives and criteria, adopting:

• The main changes in objective weightings for (C) and

(B) Equal objective weighting, unequal criterion

(D) compare with (A) and (B) are that two objectives

weighting

(Environment, Cost) are down-weighted (to 5%

(C) Unequal objective weighting, equal criterion

each), while three objectives (city centre access, city

weighting

centre mobility, economic performance) are up-

weighted (to 20% each). However, we note that this

(D) Unequal objective weighting, unequal re-weighting of objectives has resulted in very little

criterion weighting.

change in the relative rankings of the ten options.

• It was noted in the first section of this table that AT’s

intention was to give particular weight to the project

objective 4 (‘a sustainable transport solution that

minimises environmental impacts’) and objective 5

(‘significantly contribute to lifting and shaping

Auckland’s economic growth’). In our

interpretation, project objective 4 best corresponds

to assessment objective ‘Environment’ and

objective 5 to ‘Built Environment’. But, in the

sensitivity testing for objective weightings,

‘Environment’ has been sharply down-weighted

(from 12.5% to 5.0%) and ‘Built environment’ has

been marginal y down-weighted (from 12.5% to

10.0%). Our conclusion is that the current sensitivity

tests do not reflect the relative importance of the

various project objectives as advised by AT

management.

• We have a substantial concern about the relative

weightings adopted between 'benefit' objectives

and criteria and 'cost' objectives and criteria (refer

item F above). The current base objective

weightings (A) result in a weighting for 'benefit'

objectives against cost objectives of 87.5%: 12.5%;

while the reweighted objectives result in a ratio of

95%: 5%.

• We note that, for a project of this nature,

conventional economic evaluation typical y shows a

broad comparability between the magnitude of

benefits and the magnitude of costs (i.e. a BCR ratio

in the order of 1.0). This would suggest that, from a

socio-economic perspective, the appropriate

balance between benefit objectives (in total) and

cost objectives would be expected to be in the order

of 50%: 50%. It would be of interest to examine the

results of sensitivity tests on these lines.

• Indicatively, we note that the cost range between

the 10 options is likely to be in the order of $2 bil ion

(capital and operating, PV terms, over the project

life). This cost range would equate to a difference of

two rating points (-2 compared with 0) on the cost

IWA/N207/Rep/1553

21 July 2015

9

Ian Wal is Associates Ltd

objective, i.e. around $1.0 bil ion per one rating

point difference. We suggest that some thought be

given to the 'value' (in wil ingness-to-pay terms) that

society might reasonably give to a score difference

of one rating point on each of the seven 'benefit'

objectives. If this value is considered to be

significantly lower than $1 bil ion, then this benefit

objective should, logical y, be given lower weighting

than the cost objective; or vice versa if the value is

considered to be higher. It would also be worth

considering a similar question for al the 'benefit'

objectives combined: the logic of weighting al

objectives equal y, as has been done at present, is

that a one point higher rating across al of the

benefit categories would be worth in the order of

seven times the $1.0 bil ion per point cost advantage

on the cost objective.

• We suggest that the treatment of the cost objective

in the MCA evaluation needs re-consideration, with

a choice between:

(i) re-assessing the weighting to be given to the cost

objective, in the light of the above comments; or

(i ) not attempting to include the cost objective in

the MCA, but addressing the costs v benefits

trade-off separately (eg in the economic case

assessment).

The present approach is a very unsatisfactory solution.

J. Summary of Option Assessment Findings

The MCA findings indicate (based on the objectives, • In regard to point (i), while ‘real-world’ experience

criteria and scoring system used):

indicates some advantages for LRT-based solutions

(i) a strong superiority for al the LRT-based

over bus-based solutions in similar situations, it

options over the bus-based options. They also

would general y suggest a closer balance between

indicate a similarly strong superiority for the

the two types of solutions than is indicated by the

LRT-based option 5 over the BRT-based option

MCA results.

7: apart from the mode/technology involved, • In regard to point (i ), we find that the sensitivity

these two options are very similar in terms of

tests undertaken are not consistent with the advice

route, network, services, etc.

provided by AT management on the relative

(i ) The ordering of options is very insensitive to the

priorities of the various objectives.

different criterion weightings tested.

• In regard to point (i i), we find that the attempt to

(i i) The ordering of options is very insensitive to

include the cost objective in a framework otherwise

major changes in their relative costs.

including only ‘benefit’ objectives has not been

successful or helpful. We suggest that further

consideration needs to be given to this, with one

option being to exclude costs from the MCA

assessment and to address cost v benefit trade-offs

elsewhere (eg in the economic case).

IWA/N207/Rep/1553

21 July 2015

10

Ian Wal is Associates Ltd

ANNEX A: Study Objectives

(

Source: Light Rail for Auckland: Potential Peer Review – Terms of Reference).

IWA/N207/Rep/1553

21 July 2015

11

Document Outline